House prices to rise 20-30pc from pre-COVID levels

In the AFR I write today that it is amusing reading all the current hysteria about Aussie housing, often from the same folks who were absolutely convinced home values would plummet 10 per cent to 20 per cent (if not by more) only nine months ago. Excerpt enclosed:

We were shouted down back then for predicting modest house price declines of 0 to 5 per cent over just six months (in practice, prices fell 2 per cent nationally across metro and non-metro markets), which we argued would be followed by strong capital gains of 10 to 20 per cent. (I don’t know anyone who shared that view at the time.)

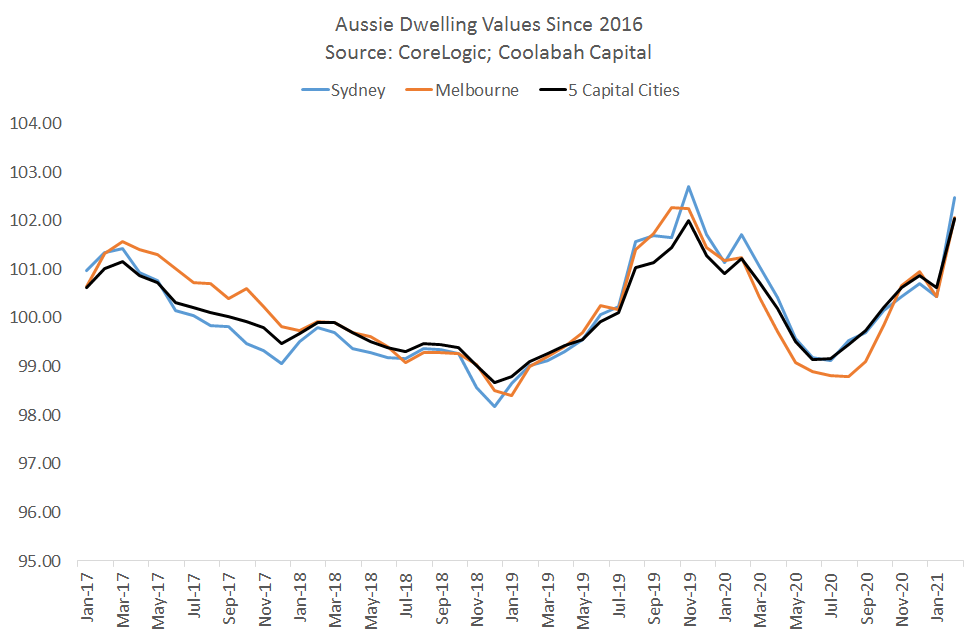

As it turned out, house prices did start recovering six months after the COVID-19 crisis hit. And since their trough in September last year, dwelling values across the five largest capital cities have climbed 6.2 per cent. That puts them about 3 per cent above their pre-COVID-19 marks.

But if we examine the current cycle over a longer lens, the facts are sobering. In the 3.5 years since the peak of the last great housing boom, Sydney dwelling values have appreciated by a grand total of just 1.13 per cent. That’s not 1.13 per cent each year, but rather the sum of the total capital gains since August 2017.

Put differently, the value of Sydney bricks and mortar has inflated by only 0.3 per cent annually over the last 3.5 years. And that’s after accounting for the 6.6 per cent jump in Sydney dwelling values since their post-COVID-19 nadir in September last year.

In Melbourne the picture is even more subdued. Home values today have not appreciated at all since their November 2017 peak. That is, there has been no net house price growth at all in Melbourne over the past 3.5 years.

Nationally across the five big capital cities, dwelling values have appreciated by less than 0.5 per cent annually since 2017. Over the same period, Aussie wages growth has been running four times higher at 2 per cent.

So while our incomes have quadrupled the rate of house price growth since 2017, the cost of borrowing has plumbed record lows. Back in 2017 a 3-year home loan carried an annual interest rate of 4.5 per cent according to the Reserve Bank of Australia. Today that is 40 per cent lower at 2.6 per cent.

Superior income growth combined with much cheaper mortgage rates have dramatically expanded our net purchasing power. That is the main reason we expected a tiny draw-down in house prices during the COVID-19 shock followed by robust capital gains of up to 20 per cent.

The projected capital gains were, in fact, predicated on a 1 percentage point drop in mortgage rates from their April 2019 levels. Now although that has played-out based on the move in variable-rate home loans, which are 1 percentage point lower, interest rates on 3-year fixed-rate products have fallen by a much more significant 1.6 percentage points.

Historically, around 8-in-10 Aussie borrowers used variable-rate loans. Due to the relative appeal of fixed-rate mortgages, that number has slumped to 62 per cent based on the January flows. That means there are now some upside risks to our housing forecasts.

For 2021 we had pencilled in total capital growth of somewhere between 10 per cent and 15 per cent across all metro and non-metro regional areas, repeatedly flagging that the probabilities were skewed to the upper-end of that range.

Since 3-year fixed-rates have now plunged 1.6 percentage points, and 1-in-4 borrowers are capitalising on these cheaper loans, total cyclical capital gains this year and next are likely to be somewhat higher at between 20 per cent to 30 per cent from pre-COVID house price levels.

There are two principal drivers of the record low, 3-year home loan rates today. The first is the RBA’s yield curve control policy that keeps 3-year interest rates fixed at 0.1 per cent. A second influence is the RBA’s 3-year term funding facility, which allows banks to borrow up to $180 billion at a cost of only 0.1 per cent annually. While the RBA has committed to maintaining its yield curve control policy, the term funding facility expires at the end of June.

These measures were designed to support the Aussie economy after it had suffered the worst economic shock since the great depression (outside of the world wars). And the shallow dip and sharp recovery in our largest store of wealth is undoubtedly attributable to the RBA and Commonwealth Treasury’s massive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus.

It is also why many more folks have jobs today than would have been the case if the RBA and Treasury had not acted so decisively. While the jobless rate did temporarily leap from 5.1 per cent to 7.5 per cent, it has dropped back down to 5.8 per cent. That is around the same level the unemployment rate peaked at during the global financial crisis.

With JobKeeper expiring in March, which banks believe could result in up to 100,000 job losses, we have a long way to go to reach “full employment”. This probably equates to an unemployment rate below 4 per cent, which should help lift wages growth up from its record-low level of 1.4 per cent currently back to its pre-GFC pace closer to 4 per cent.

The problem with this very aspirational plan is that the RBA and Treasury have found it impossible to achieve since 2008. And so rather than relying on rubbery forecasts, they have both committed to seeing the hard data before they start tightening policy, which is a sensible strategy.

It should be noted that our housing forecasts face several headwinds. First, they do not account for any regulatory measures to cool excessive credit growth. Although aggregate credit growth remains modest, it likely that our forward-thinking regulators are working on their potent “macro-prudential” playbook right now. In 2017, these policies triggered a 10 per cent decline in national prices.

Given the striking improvement in the conservatism of bank lending standards since 2014, there are not currently concerns regarding imprudent bank lending practices. There is, however, a reasonable case for the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority to ensure that non-bank lenders are held to the same exhaustive responsible lending benchmarks that it imposes on the banking sector. If this loop-hole remains, non-banks will simply accumulate market share from banks by offering borrowers looser terms and conditions, such as higher loan-to-value ratios and smaller surplus income servicing requirements.

Another headwind could be a future normalisation in banking funding costs. As banks slowly replace the RBA’s term funding facility with more conventional senior bond issuance, it would be reasonable to assume that 3-year home loans rates will have to climb somewhat.

One thing that is not impacting variable-rate home loans or 3-year fixed-rate products is the RBA’s longer-dated quantitative easing (QE) policy. This involves it buying 5-year to 10-year government bonds to slow the normalisation in long-term interest rates as the global economy recovers from the pandemic. By doing so, the RBA has kept the Aussie dollar materially lower than it would otherwise be, supporting local businesses that export products or compete with foreign imports. Indeed, there is some evidence that as the RBA learns how to better calibrate its QE policy, it is becoming more effective over time.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 13 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch

1 topic