How much should I allocate to domestic versus global bonds?

For investors in relatively small countries such as Australia and New Zealand, one of the key questions to address is ‘How much should I allocate to domestic versus global bonds?’ Though there are many aspects associated with addressing this question, which is better ultimately depends upon the risk/return profile of the investor and the characteristics of the respective markets.

To assist in providing a more structured approach to addressing this question it is useful to take a closer look at some of the more important considerations which may drive investor preferences for one over the other.

Diversification

By far the most significant advantage of investing in global bond markets is that it provides the investor with a greater level of diversification compared to a single market. When dealing with global bond markets diversification can be viewed as occurring at several levels. The most obvious aspect of increased diversification is with respect to the greater number of issuers spread across different industries and geographical regions.

Not only is the proportional exposure to any single issuer reduced but also, by allocating across a range of geographies, the exposure to any single economic/financial cycle is diversified. Accordingly, global bond markets can reduce the level of volatility exhibited by fixed-income portfolios in comparison to single-market exposure.

The second aspect of return diversification occurs as a by-product of currency hedging. Most global bond portfolios are fully hedged with respect to currency risk. There is inevitably a mismatch between the term of the currency hedging, which is via shorter duration derivative instruments, and the longer duration of the underlying global bond portfolio. It is due to this mismatch in durations that the return profile of the currency hedge will differ from that of the underlying bonds. To the extent that the two return profiles are less than perfectly correlated, there will be a level of diversification with respect to shorter-term returns arising from the action of hedging currency risk.

The greater levels of diversification from global bond markets will tend, all else being equal, to result in a superior risk/return profile over single markets denominated in the home currency. Yet it is against the heightened levels of diversification associated with global bond markets that investors need to weigh up some potential cons.

Real exchange rate risk

Investors in fixed-income markets need to consider whether the nominal or real outcome is more important from an investment perspective.

To better understand the distinction, consider that one of the key factors impacting fixed income yields, both directly and indirectly, is the inflation rate. Due to this interlinkage, when market expectations for inflation are in line with realised inflation, bonds will tend to provide investors with an inflation hedge.

It follows that under such an assumption it is reasonable to expect that, over the longer term, domestic bonds will protect an investor against the impacts of local inflation.

By contrast, global bond portfolios will be impacted by their respective inflation cycles with the hedging of currency exposures back to the local currency providing a linkage between global and domestic interest rate cycles. This linkage between global and domestic interest rates occurs as theoretically currency hedging should equate the returns on domestic and global bond markets thereby making the investor indifferent.

Unfortunately, due to a range of factors currency hedging may not in practice result in an equalisation of global and domestic bond returns. Where the linkage is less than perfect the investor is exposed to Real Exchange Rate Risk. The assumption of a real exchange rate exposure means that the local investor is no longer protected against the domestic inflation cycle.

It follows that within a fully hedged bond portfolio the extent to which investors will favour a bias to domestic bonds will be determined by

- (a) the magnitude of real exchange risk and

- (b) their sensitivity to the impact associated with assuming a greater level of real exchange rate exposure.

At the extreme, investors wanting to use their fixed-income holdings to offset liabilities linked to local inflation will be much more sensitive to real exchange rate risk.

Default risk and quality

An assumption that has been maintained to date is that ‘all else is equal’ which is unlikely to be the case. Often there will be differences in the overall quality of domestic and global bond markets.

Where an investor is moving from a lower quality local market to a higher quality global market there can be a ‘win-win’ situation. Under such a scenario by moving from domestic to global bond markets the investor can achieve both a higher level of diversification and a higher level of overall credit quality. The case is less clear-cut where the opposite holds.

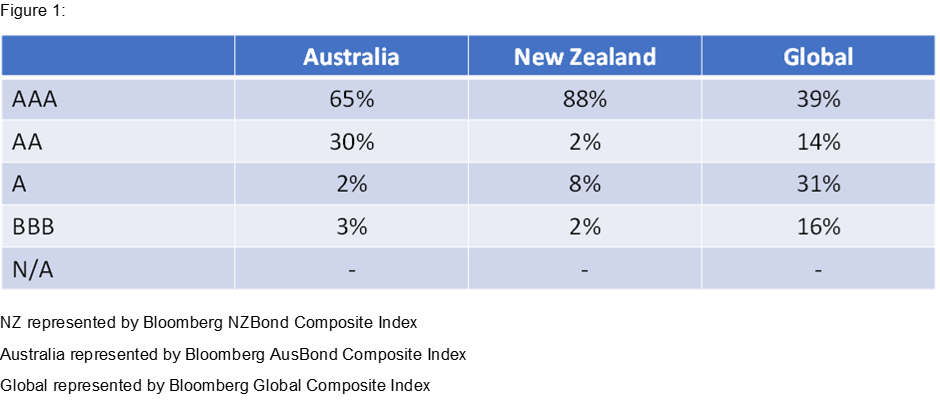

When considering the concept of quality between markets, there is a range of dimensions to be assessed. The first is to consider the overall exposure to the different official credit rating bands. Figure 1 compares the official credit rating quality for the Australian and New Zealand bond market with that for the global bond market.

As can be seen, the Australian and New Zealand markets are predominantly AAA exposures while global bond markets have a lower overall level of credit quality. Most obviously the level of BBB exposure in global bond markets is more than five times that of either the Australian or New Zealand bond market. A higher allocation to BBB exposures becomes a particularly relevant consideration for investors during economic/financial downturns given the potential for a negative ratings migration to push BBB issuers below investment grade.

The second dimension to consider is the underlying nature of the exposure. More specifically even if the credit ratings are the same there is a major difference in quality depending on whether the exposure is government or non-government in nature. The reason for the difference in risk profiles is that governments have access to taxation and other macro policy measures as a means of repaying local currency debt. Indeed, at the extreme governments can resort to printing money to repay the local currency debt outstanding. Such levers are obviously unavailable to non-government issuers. The existence of such policy options means that it is, in effect, impossible for governments to default on local currency debt. As government issuers possess greater flexibility in the ability to repay local currency debt the result is an overall lower level of default risk even if the credit ratings for government and non-government bonds are the same.

As Figure 2 highlights the government exposure within the Australian and New Zealand markets is materially greater than that in the global fixed-income market pointing to lower risk characteristics.

Ironically the existence of such policy levers also means that when dealing with government issuers there are potential differences in creditworthiness that go beyond simply the credit rating or risk of legal default. It is accordingly important for investors to differentiate between the risk of ‘legal default’ and the risk of ‘economic default’.

Though ‘legal default’ for well-rated sovereigns may be unlikely, a more important risk is that of ‘economic default’ as sovereign issuers seek ways to ‘more fairly’ distribute the costs associated with reducing the level of debt.

While legal default involves a government simply refusing to honour its legal commitments to bondholders, economic default is more insidious and involves governments pursuing policies aimed at reducing the effective cost of servicing the local currency debt on issue. Such measures as allowing higher inflation, currency depreciation or repressing interest rates are just as real an enemy to the effective returns earned by local currency bond investors over time as ‘legal default’.

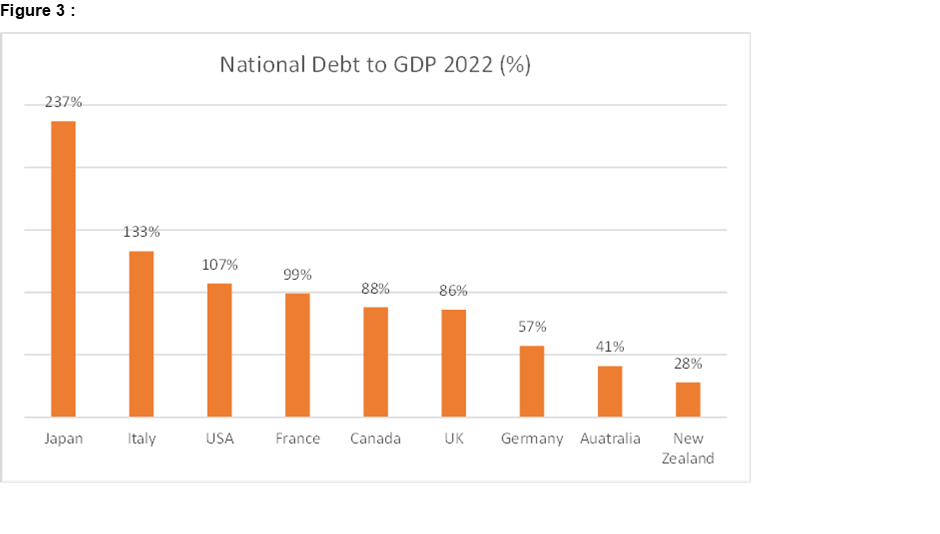

Not surprisingly the risk of ‘economic default’ rises as the debt burden faced by governments increases. Figure 3 shows the level of National Debt as a Percentage of GDP for a selection of key developed countries that constitute a material portion of the government component of global bond indices. Against such an economic backdrop certain countries such as Australia and New Zealand stand out as maintaining materially better fiscal and demographic positions than others.

Overall, the comparison of quality characteristics highlights how greater caution should be exercised by investors who may be reallocating from domestic markets which exhibit relatively high credit quality and strong fundamentals to global markets which may exhibit materially weaker characteristics. For Australian and New Zealand investors, no matter which way an investor considers risk, the local markets come out as being appreciably higher quality than their global counterparts. Where bonds are being considered as the ‘safe’ allocation within a portfolio, such differences in risk characteristics should be explicitly ‘weighed up’ by investors when deciding how much of their assets to allocate to domestic versus global bonds.

Stability of distributions

As global bond portfolios are fully hedged, then there can be an impact on distributions. Whether there is an impact on distributions will depend on how distribution income is managed. The potential for an impact on distributions is due to the mismatch between the timing of realised gains and losses from the shorter-dated currency hedges versus those on the longer-dated underlying assets.

Unless an investor takes active steps to specifically match up the realised gains/losses on the hedge with the offsetting gain/loss on the underlying asset there will be an impact on distributable income. Depending on how these differences in the realisation of gain/losses are managed, global bond funds are at risk of exhibiting greater volatility in distributions than local currency bond portfolios. For investors utilising fixed income as a source of stable distributions how the distributions on a global bond fund are managed can have an impact on their relative attraction.

For investors in a small relatively concentrated markets such as Australia or New Zealand, the attraction of global bond markets is the increase in the level of diversification and value-adding opportunities.

When included in a portfolio, global bond exposures provide the opportunity for investors to achieve materially higher levels of risk-adjusted returns. Yet these higher levels of risk-adjusted returns are not a free lunch. Investors may be assuming additional risks when allocating from a relatively low risk market such as Australia and New Zealand to an offshore global bond market. It is only by ‘weighing up’ these risks with the potential rewards that an investor can determine which allocation between these two exposures is most consistent with their investment objectives.

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

You can follow my profile to stay up to date with other wires as they're published – don't forget to give them a “like”.

2 topics

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...