6 principles for times of turmoil

Capital Group

You wouldn’t be human if you didn’t fear loss.

Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman demonstrated this with his loss aversion theory, showing that people feel the pain of losing money more than they enjoy gains. The natural instinct is to flee the market when it starts to plummet, just as greed prompts people to jump back in when stocks are skyrocketing. Both can have negative impacts.

But smart investing can overcome the power of emotion by focusing on relevant research, solid data and proven strategies. Here are six principles that can help fight the urge to make emotional decisions in times of market turmoil.

1. Market declines are part of investing

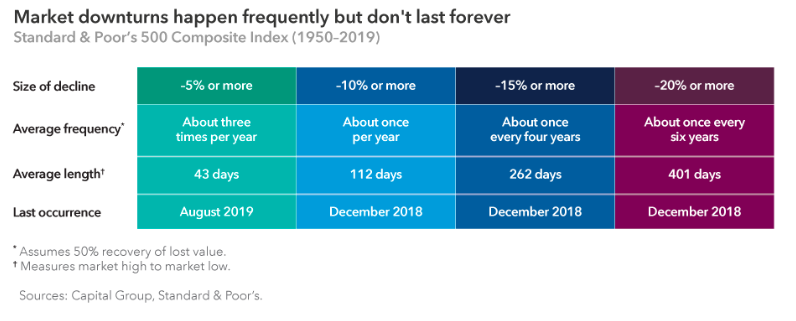

Stocks have risen steadily for most of the last decade, but history tells us that stock market declines are an inevitable part of investing. The good news is that corrections (defined as a 10% or more decline), bear markets (an extended 20% or more decline) and other challenging patches haven’t lasted forever.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index has typically dipped at least 10% about once a year, and 20% or more about every six years, according to data from 1950 to 2019. While past results are not predictive of future results, each downturn has been followed by a recovery and a new market high.

2. Time in the market matters, not market timing

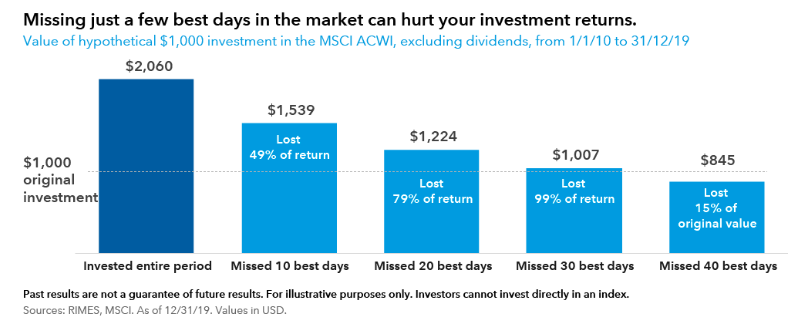

Market corrections are not uncommon and should not be unnerving. However, when investors see the value of their investments dwindling, their aversion to losses can compel them to sell. And once they have sold, they stay out of the market.

But that can cost investors dearly as those who sit on the sidelines risk losing out on periods of meaningful price appreciation that follow market downturns. Even missing out on just a few trading days can take a toll. A hypothetical investment of $1,000 in the MSCI ACWI made in 2010 would have grown to $2,060 by the end of 2019. But if an investor missed the 30 best trading days of that period, they would have ended up with 99% less.

3. Emotional investing can be hazardous

Kahneman won his Nobel Prize in 2002 for his work in behavioural economics, a field that investigates how individuals make financial decisions. A key finding of behavioural economists is that people often act irrationally when making such choices.

Emotional reactions to market events are perfectly normal. Investors should expect to feel nervous when markets decline, but it’s the actions taken during such periods that can mean the difference between investment success and shortfall.

One way to encourage rational investment decision-making is to understand the fundamentals of behavioural economics. Recognising behaviours like anchoring, confirmation bias and availability bias may help investors identify potential mistakes before they make them.

4. Make a plan and stick to it

Creating and adhering to a thoughtfully constructed investment plan is another way to avoid making short-sighted investment decisions — particularly when markets move lower. The plan should take into account a number of factors, including risk tolerance and short- and long-term goals.

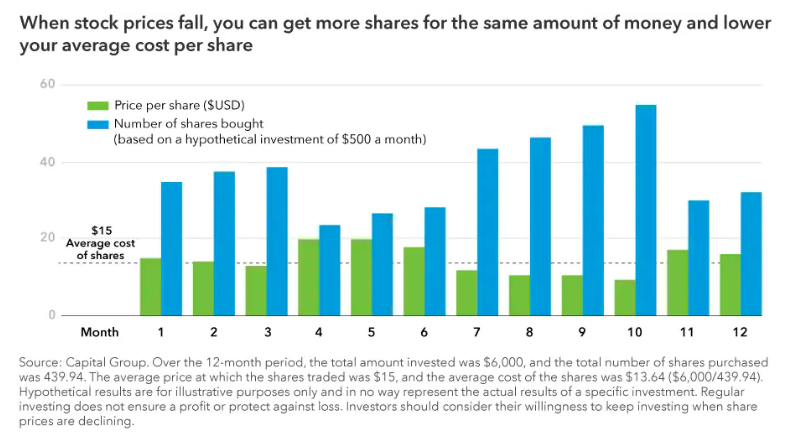

One way to avoid futile attempts to time the market is with dollar cost averaging, where a fixed amount of money is invested at regular intervals, regardless of market ups and downs. This approach creates a strategy in which more shares are purchased at lower prices and fewer shares are purchased at higher prices. Over time investors pay less, on average, per share. Regular investing does not ensure a profit or protect against loss. Investors should consider their willingness to keep investing when share prices are declining.

Retirement plans, to which investors make automatic contributions with each paycheck, are a prime example of dollar cost averaging.

5. Diversification matters

A diversified portfolio doesn’t guarantee profits or provide assurances that investments won’t decrease in value, but it does help lower risk. By spreading investments across a variety of asset classes, investors can buffer the effects of volatility on their portfolios. Overall returns won’t reach the highest highs of any single investment — but they won’t hit the lowest lows either.

For investors who want to avoid some of the stress of downturns, diversification can help lower volatility.

6. The market tends to reward long-term investors

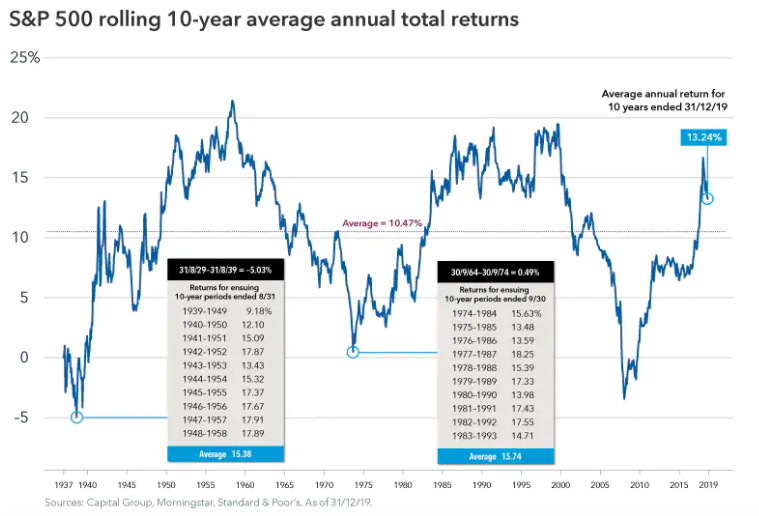

Is it reasonable to expect 30% returns every year? Of course not. And if stocks have moved lower in recent weeks, you shouldn’t expect that to be the start of a long-term trend, either. Behavioural economics tells us recent events carry an outsized influence on our perceptions and decisions.

It’s always important to maintain a long-term perspective, but especially when markets are declining. Although stocks rise and fall in the short term, they’ve tended to reward investors over longer periods of time. Even including downturns, the S&P 500’s average annual return over all 10-year periods from 1937 to 2019 was 10.47%.

It’s natural for emotions to bubble up during periods of volatility. Those investors who can tune out the news and focus on their long-term goals are better positioned to plot out a wise investment strategy.

Position your portfolio to navigate through cycles

Capital Group believes in a smarter way of investing that combines individuality and teamwork into a tailored approach to help investors meet their goals. Find out more, by clicking 'CONTACT' below.

3 topics

1 contributor mentioned

Matt Reynolds is an Investment Director at Capital Group. He has over 20 years of industry experience including head of Australian equities – core at Colonial First State Global Asset Management. He holds a bachelor's degree in Economics from The...

Expertise

Matt Reynolds is an Investment Director at Capital Group. He has over 20 years of industry experience including head of Australian equities – core at Colonial First State Global Asset Management. He holds a bachelor's degree in Economics from The...