What you need to know before investing in bonds

Government bonds were traditionally favoured for their non-correlation to equity markets. But even before COVID arrived on our doorstep more than two years ago, the movement of bonds and equities has been more correlated (though in most cases, stocks have sold off more sharply). In the first part of the series, four contributors weighed into the debate about the relevance of the 60/40 model of a balanced portfolio. In this second part, they discuss some of the most important things to consider before adding bonds to your investment mix.

Key takeaways

- Where are bond yields headed?

- The importance of duration

- How inflation affects bond yield

In January this year, bonds were leading the underperformance of global markets, until the selloff in equities and other assets began in April. This was spurred by rising inflation that prompted central banks to start lifting interest rates, kicked off by the US Fed and the Bank of England. In response, the bond yield on the US-10-year treasury bill hit a 3-year high of 2.93%.

With yields pulling back since then, some are suggesting further upside here might be limited. This highlights the difficulty of using this metric – yield refers to the income from a fixed income asset including coupon payments and the amount received at maturity – to determine your allocation to bonds. In the following wire, I ask the following four contributors how bond yield movements should affect the way investors think about their allocation to fixed income.

- Alexandre Ventelon, head of research and investment strategy Australia, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management

- Simon Doyle, CIO and head of multi-asset, Australia, Schroders Australia

- Jerome Lander, chief investment officer, WealthLander

- Chad Padowitz, co-CIO and founder, Talaria Asset Management.

Further bond yield upside is questionable

Alexandre Ventelon, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management

Bond diversification benefits over the long term are unquestionable. But in the short term, periods of negative performance may arise. Recently, investors have been affected by an exceptional combination of factors that have negatively impacted some of the main factors that drive bond returns. In particular:

- Yields were depressed at the beginning of this year (for example the Bloomberg US Treasury Index offered only a 1.2% yield to maturity). In addition, the yield curve was relatively flat, which provided little “carry” (which refers to the difference between the yield on a longer-maturity bond and the cost of borrowing) as a cushion against an adverse move in yield.

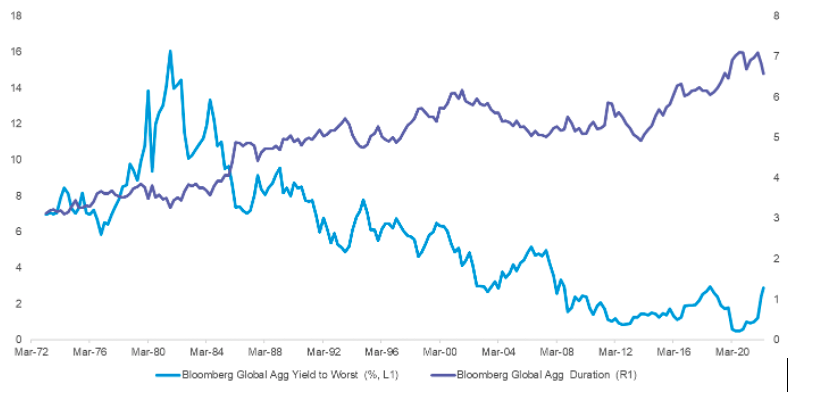

- Duration, or the sensitivity of most bond indices, was near historical highs at the start of this year as institutions extended the maturity of their debt to “lock in” cheap interest rates. This was in addition to the duration of bonds increasing mechanically as yields fall. Essentially, this resulted in an over-sensitivity of bonds to a change in yields.

The acceleration in realised inflation from the second half of last year has also augmented the rise in yields. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of a bond's future cash flows, and in the US, it is currently at the highest level in 40 years.

Treasury yields and duration have been going in opposite directions

This highlights the need for investors to be cautious in increasing their exposure to bonds until they believe yields fully reflect the interest rate hiking path, which is also related to the inflation outlook.

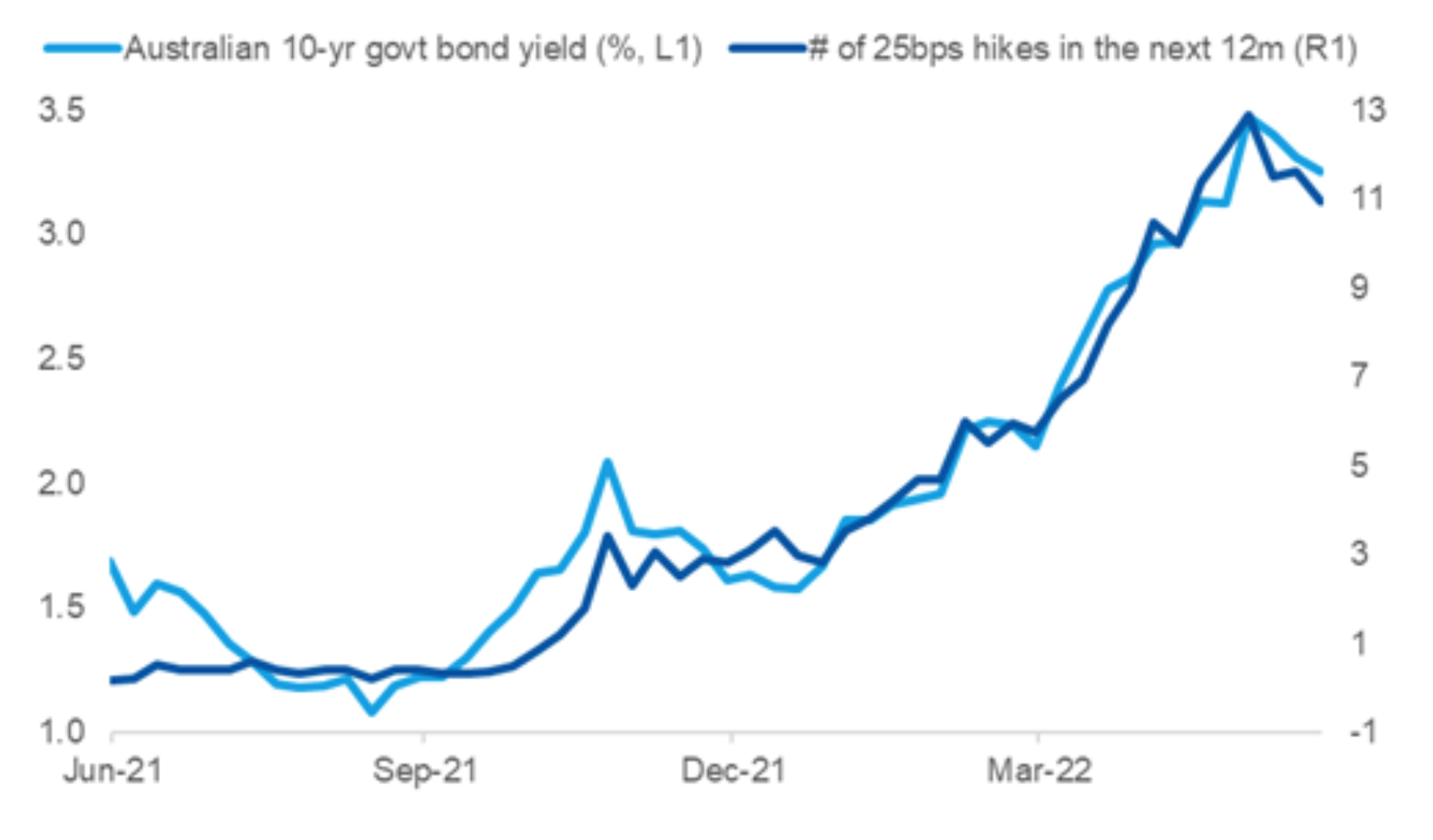

Given our view that economic growth will likely slow down markedly from here, and that inflation will gradually recede towards central banks’ targets into next year, further yield upside looks limited. In this context, we currently consider the market pricing of future rate hikes as too aggressive based on our forecasts of 10-year treasury yields.

We also see floating rate instruments as a good way to complement an allocation to government bonds given our expectation of cash rates at 1.75% in Australia and 2.625% in the US by the end of this year and also given these securities carry near-zero duration.

Treasury yields have followed the trajectory of the RBA’s hike anticipations

Source: Bloomberg, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management Research

Bond investors are probably through the worst

Simon Doyle, Schroders

Fixed income is still an incredibly important part of any portfolio. The breadth of the asset class is what makes it attractive, as it covers a huge array of investment opportunities. These range from cash and cash-like assets and government bonds through to high yielding and sometimes high risk corporate and emerging market bonds.

Over the last few years, we’ve seen the risks and opportunities of all parts of the fixed income landscape on display. Rising yields are only one aspect of the complexity of holding fixed income investments in a portfolio.

Active management of fixed income has allowed investors (and their fund managers) to manage and mitigate the impact of rising bond yields on portfolios by managing duration – the length of time before assets mature – even if they’re not able to completely avoid some drag to returns. But yields adjust quickly and we’re seeing this play out currently. It’s quite possible that the peak in bond yields has already been seen, with yields having quickly reset to align with expectations of central bank rate hikes.

I started covering bonds just before the infamous bond market crash of 1994. Of course, it was painful while it was occurring, with the sell-off lasting around six months. But the biggest mistake investors made was getting out of bonds, given the subsequent strength of the rally. Things are different today, but this context is important, as it is highly likely that most of the pain for bond investors has passed.

When fundamentals change, alter your allocation

Jerome Lander, WealthLander

We believe investors need to change their asset allocation substantially in response to the changing prospects and valuations of different assets. For example, if bond yields are expected to rise, bonds with interest rate risk (longer duration) may be less attractive than otherwise as bonds sell-off.

Bonds can also be unattractive if the yields are too low – and artificially low – as they have been in recent years. We’ve written about the risks to bonds in prior periods and have had very low to no allocations then.

In recent months, we have seen one of the largest ever sell-offs in long-duration bonds. It was interesting to see so few bond managers avoid the sell-off – this highlights the advantages of a multi-asset class approach that isn’t wedded to any one asset class and is prepared to zero-weight an asset class.

Asset duration is also key

Chad Padowitz, Talaria Asset Management

Rising bond yields are as much of an opportunity as they are a risk. As yields rise, they enable investors to deploy capital at higher contractual rates of return than has been possible for many years.

Importantly this should be viewed in the context of inflation expectations of the period of the bond, as it’s the real return that ultimately matters. Duration matters a lot in a time of big moves in interest rates.

As an example, owning a 10-year bond with a yield of 1% that immediately reprices to 3% would create an immediate loss of nearly 15% as the bond price goes down. Whereas a 1-year bond would hardly be affected, as the bond’s principal equity would be returned within a short period of time. In short, if you expect rates to keep going up then you would want shorter duration bonds, because of this shorter time before the assets mature and the investor gets their money back.

Stay up to date with this series

Make sure you "FOLLOW" my profile to be notified when later parts of this series are published. In part one, our contributors discussed whether the 60-40 model of portfolio construction remains relevant. And in part three, they each name one aspect of the market they believe all investors should consider.

3 topics

5 contributors mentioned