Howard Marks' 4 signs of the top (and other incredibly pertinent lessons for 2025)

In January 2000, Oaktree Capital co-founder and co-chairman Howard Marks wrote a note entitled bubble.com.

He closed the 14-page note by saying:

"To say technology, internet and telecommunications stocks are too high and about to decline is comparable today to standing in front of a freight train. To say they have benefited from a boom of colossal proportions and should be examined very skeptically is something I feel I owe you," Marks wrote.

I think you can guess what happened next.

Now, 25 years on, Marks is looking back at that memo and asking if we're in another stock market bubble. The memo gifts excellent insight into investing psychology, his own investing principles, and the idea of risk.

In this wire, I'll summarise this current memo and make some comparisons to the note from 25 years ago. I'll finish by throwing in some interesting stats from Bridgewater Associates which, in my humble opinion, may add some weight (or at least colour) to Marks' argument. Right at the outset, let me forewarn you - this will be a long wire and for good reason.

Firstly, what constitutes a bubble?

To Marks, it's not a specific statistic that signals a bubble but rather, a mindset. That mindset, he adds, is based on four psychological points. You could say, to paraphrase one Marcus Padley, these are Marks' four signs of the top:

"For me, a bubble or crash is more a state of mind than a quantitative calculation," Marks said. "In my view, a bubble not only reflects a rapid rise in stock prices, but it is a temporary mania characterised by – or, perhaps better, resulting from – the following:

- Highly irrational exuberance,

- Outright adoration of the subject companies or assets, and a belief that they can’t miss,

- A massive fear of being left behind if one fails to participate (‘‘FOMO’’), and

- Resulting conviction that, for these stocks, “there’s no price too high.”

Not even Newton is immune to the bubble

We've seen lots of this in financial markets over time. In Marks' memo from 25 years ago, he references the South Sea Bubble and how one of the most intelligent men in modern history is not immune to big busts.

"Sir Isaac Newton, like so many investors over the years, couldn't stand the pressure of seeing those around him make vast profits. He bought back the [South Sea Company's] stock at its high and ended up losing £20,000. Not even one of the world's smartest men was immune to this tangible lesson in gravity!," Marks wrote in his 2000 memo.

What's even more amazing is that Newton sensed there was a speculative bubble occurring and he had sold his stake at the prior princely sum of £7,000. The point is - in a bubble - there is no price that is too high to keep entering a stock. I wonder if this sounds familiar at all to anyone in today's market? (Hint: The Magnificent Seven, and in particular, Nvidia.)

"When you can’t imagine any flaws in the argument and are terrified that your officemate/golf partner/brother-in-law/competitor will own the asset in question and you won’t, it’s hard to conclude there’s a price at which you shouldn’t buy," Marks says today.

"Whenever I hear “there’s no price too high” or one of its variants – a more disciplined investor might say, “of course there’s a price that’s too high, but we’re not there yet” – I consider it a sure sign that a bubble is brewing," he adds in his January 2025 note.

Is the bull market reaching its dessert course?

Drawing on a lesson he first learned 50 years ago (coincidentally the last time Marks analysed individual stocks in depth), Marks argues there are three stages of a bull market.

- "The first stage usually comes on the heels of a market decline or crash that has left most investors licking their wounds and highly dispirited. At this point, only a few unusually insightful people are capable of imagining that there could be improvement ahead.

- In the second stage, the economy, companies, and markets are doing well, and most people accept that improvement is actually taking place.

- In the third stage, after a period in which the economic news has been great, companies have reported soaring earnings, and stocks have appreciated wildly, everyone concludes that things can only get better forever."

That last point is perhaps the most important conclusion of them all. How many times have you read in the press that things will only get better for AI adoption? I know I have. Chief among them, Daniel Ives at Wedbush Securities who has argued that Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang is the "Godfather of AI" and believes Nvidia and Apple could reach a market capitalisation of US$4 trillion.

In other words, it's not what is right but rather what investors perceive is right.

"Perhaps for working purposes we should say that bubbles and crashes are times when extreme events cause people to lose their objectivity and view the world through highly skewed psychology – either too positive or too negative," Marks hypothesises.

Bubbles are caused by shiny, new things (invariably)

Bubbles are, invariably, caused by shiny new things. From the Nifty Fifty of the 1960s to sub-prime mortgages in the mid-2000s, there's examples literally everywhere. So why are bubbles always caused by "new" phenomena?

"But if something’s new, meaning there is no history, then there’s nothing to temper enthusiasm," Marks offers. "When a whole market or a group of securities is blasting off and a specious idea is making its adherents rich, few people will risk calling it out."

This lesson applies now as it did a quarter-century ago. TMT stocks were, in 2000, being touted as world-changers. And Marks wasn't even disagreeing with that argument! He was just disagreeing with how much it's worth.

"I have absolutely no doubt that these movements are revolutionising life as we know it, or that they will leave the world almost unrecognisable from what it was only a few years ago. The challenge lies in figuring out who the winners will be, and what a piece of them is really worth today," Marks wrote in 2000.

This leads back to a core view Marks revisits 25 years later: There’s usually a grain of truth that underlies every mania and bubble. It just gets taken too far.

And another tenet comes right after it: When something is new, the competitors and disruptive technologies have yet to arrive. The merit may be there, but if it’s overestimated it can be overpriced, only to evaporate when reality sets in.

...but leaders can and do change

The leaders of 2000 are certainly not the leaders heading into 2025. In his 2025 note, Marks attaches the 20 biggest companies back in 2000. Only one name is still standing from the list of 25 years ago and only seven are still in the top 20 (these lucky names are italicised.)

- Microsoft (Still on top after 25 years)

- Merck

- General Electric

- Coca-Cola

- Cisco Systems

- Procter & Gamble

- Walmart

- AIG

- Exxon Mobil

- Johnson & Johnson

- Intel

- Qualcomm

- Citigroup

- Bristol-Myers Squibb

- IBM

- Pfizer

- Oracle

- AT&T

- Home Depot

- Verizon

"In bubbles, investors treat the leading companies – and pay for their stocks – as though the firms are sure to remain leaders for decades. Some do and some don’t, but change seems to be more the rule than persistence," Marks offers. "Investors are assuming Nvidia will demonstrate persistence."

The moral of this long story: It's the price you pay that matters most

Marks wrote the following back in 2000 - and it's so utterly true today:

"Eventually, this is what it comes down to. It's not enough to buy a share in a good idea, or even a good business. You must buy it at a reasonable (or, hopefully, a bargain) price. Vast amounts of ink have been devoted to the valuations being put on the new companies," Marks wrote back then.

"A “top” in a stock, group or market occurs when the last holdout who will become a buyer does so," he added.

Put a different way, it's time in the market over timing the market but it's the price you pay above all else.

"It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the return on an investment is significantly a function of the price paid for it. For that reason, investors clearly shouldn’t be indifferent to today’s market valuation," Marks writes today.

"You might say, “making plus-or-minus-2% wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world,” and that’s certainly true if stocks were to sit still for the next ten years as the companies’ earnings rose, bringing the multiples back to earth. But another possibility is that the multiple correction is compressed into a year or two, implying a big decline in stock prices such as we saw in 1973-74 and 2000-02. The result in that case wouldn’t be benign," Marks says.

Note: He is not calling whether the S&P 500 is in a bubble. He's just saying that if it is, the clues are all there.

So what is the right price to pay?

One of the most common metric to assess a company's valuation is its price-to-earnings multiple. The key word there is multiple because, as an investor, you want to assume that a company will make profits more than just one year.

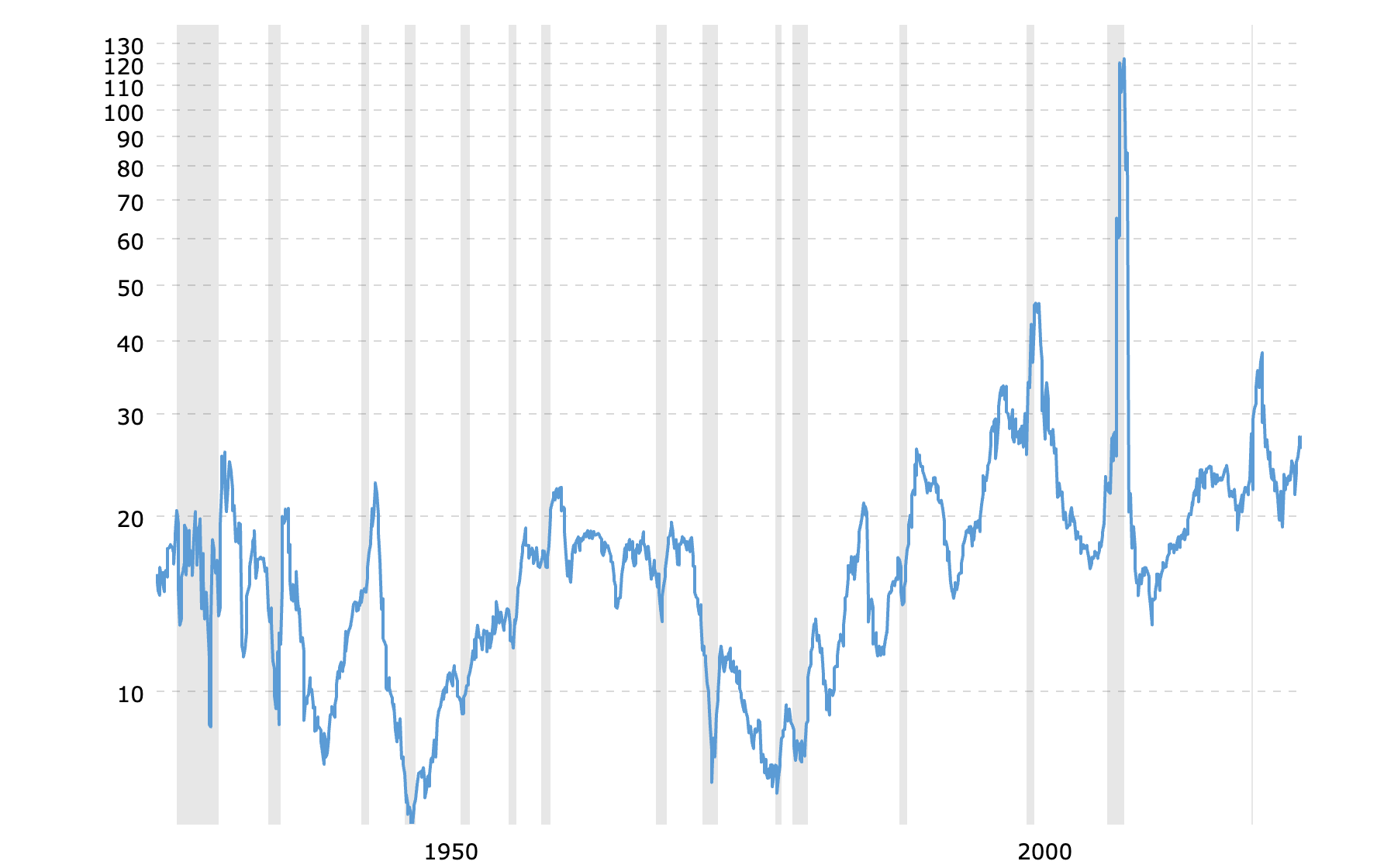

"The price of the S&P 500 has averaged roughly 16 times earnings in the post-World War II period. This is typically described as meaning “you’re paying for 16 years of earnings.” It’s actually more than that, though, because the process of discounting makes $1 of profit in the future worth less than $1 today," Marks notes in his 2025 memo.

But of course, in bubbles, the hottest stocks sell for a lot more than the market average.

"Remember the 60 to 90 times for the Nifty Fifty! Investors in 1969 were paying for companies’ earnings – even after giving them credit for significant earnings growth – many decades into the future. Did they do so consciously and analytically? Not that I recall. Investors thought of a P/E ratio as just a number... if they thought about it at all," Marks quips.

For context, here are the P/E ratios of the Magnificent Seven as of September 2024. I couldn't find anything more recent aggregated in this format but the general question still stands: How much do you want to pay for the companies that could either change the world or blow the opportunity?

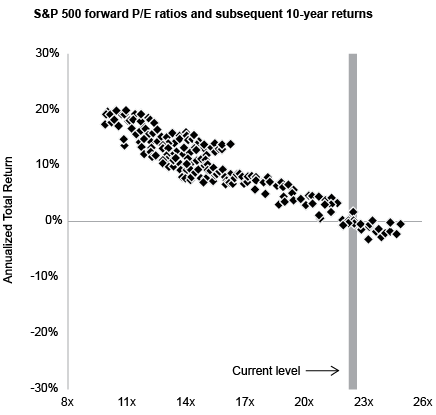

The answer to this question could be helped by this next and last graphic. The chart from JPMorgan Asset Management suggests that higher starting valuations consistently lead to lower returns. Further, when people bought the S&P 500 at P/E ratios that are in in line with today’s multiple of 22, they always earned 10-year returns between plus 2% and minus 2%.

Hardly spectacular given what you could have had.

One last related note - the high bar for stocks

This concludes my long list of key takeaways from Marks' two bubble-oriented notes. And while it could have ended at that, I couldn't not share this additional insight from Bridgewater Associates Co-Chief Investment Officer Karen Karniol-Tambour. Marks' arguments are specifically for sharemarket investors but the truth is that investors have many more options for asset allocation beyond stocks. So I feel it's prudent to share the following stats from Karniol-Tambour's note which also landed in my inbox this week:

- US equities, in aggregate, need 9% annualised EPS growth to earn a normal return above bonds. Global ex-US equities need EPS growth of just 2.5%.

- Tech is priced for higher earnings than the rest of the S&P 500

- Mag 7/AI names can earn a normal return above bonds if the basket can sustain at least 12% EPS growth. That figure is, surprise surprise, much higher than the rest of the S&P 500

- EM equities require no EPS growth to earn a better return than bonds. The exception to the rule is India.

The point of me sharing these statistics is to say that it's not just about the price you pay - it's also about what you're assuming will happen if and when you make these trades. If you believe the Wall Street sell-side, these companies are going to achieve these goals and then some. If they don't, then this market which is "priced for perfection" may be about to get an almighty reality check.

To read the entire Howard Marks memo from January 2025, click here. To read the Howard Marks memo from January 2000, download the PDF attached to this wire.

2 topics

1 contributor mentioned