If Australian Politicians Cared About Housing Affordability Here’s What They Would Do

Key Principles for Housing Policy

Before explaining each of the eight changes it is helpful to have basic principles that underlie the approach to change.

- Housing is first and foremost a place to live and secondly an investment opportunity. Low income Australians do not have an alternative to housing as a place to live, wealthier Australians do have alternative investment opportunities.

- Affordable rental accommodation is a necessity, affordable housing for purchase is a nice to have. Government policy should prioritise increasing the amount of affordable rental properties, and in doing so the cost of purchasing dwellings should fall.

- Making housing more affordable means that existing property prices are likely to fall. Governments should not try to protect wealthier property owners from price falls in housing or any other investments.

- Governments must accept that the cost of housing is ultimately determined by market forces. The focus must be on long term demand and supply factors. Policies that attempt to mandate the construction of a small portion of affordable housing won’t work if the overall demand exceeds supply.

With the principles for change laid out, here are the eight recommended actions.

Reduce the Migration Intake

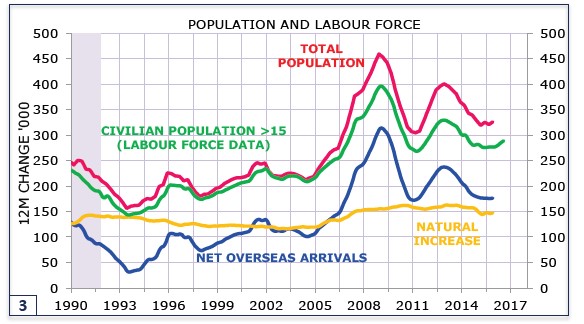

The primary driver of the demand for housing in Australia in the last ten years has been very strong population growth. In the last decade population growth in the US was 0.8% per annum and in Europe 0.1%. In Australia, the population has increased from 20.4 million to 24.1 million, equating to 1.7% per annum. As shown in the graph below natural growth (births minus deaths) and migration have both contributed to a population surge.

Source: Minack Advisors

A lack of affordable housing is just one of the costs that Australians are paying for rapid population growth. Increased travel time to work and recreation as roads and public transport become more crowded is another obvious cost. Increased state and federal government spending on roads, public transport, schools and hospitals to accommodate the additional demand for services is another.

The preoccupation with headline GDP growth, which is in large part due to population growth, means ignoring the negative impacts on GDP per capita and quality of life. This is particularly apparent in the high growth cities of Sydney and Melbourne where most migrants choose to live. Given the population growth, it is no surprise that these two cities have seen far larger growth in house prices in the last decade compared to Brisbane and Perth.

The make-up of Australia’s migration intake shows that much can be done without dramatic changes. Family migration and the majority of skilled migration could be curtailed with little negative impact. Skilled migration should be limited to specialist occupations that Australians cannot easily be trained to fill. For example, there are millions of unemployed and underemployed Australians who could be quickly trained to be chefs. Australian restaurants need to train more chefs and pay higher wages to attract potential employees rather than importing chefs. There is also an issue with willingness to work amongst some Australians. Australia relies heavily upon seasonal workers and backpackers for fruit picking when regional areas have amongst the highest youth unemployment rates.

Lower and Equalise Income Taxes

The debate over negative gearing and capital gains tax deductions is often cited as part of the housing affordability problem. However, the underlying issue is that the top marginal tax rates are too high, thus higher income Australians seek out these schemes in order to maximise their after-tax investment returns. Australia needs to have lower and simpler income tax, with all individuals, companies and trusts subject to a top marginal tax rate of 20-25%.

A lower top tax rate would be accompanied by removal of loopholes, with capital gains tax reductions for assets held over 12 months eliminated. These changes would incentivise work, saving and investment in balanced ways, rather than the existing system that penalises work and rewards property and equity investments. The funding for a lower but broader top tax rate would come from a higher and broader GST, a crackdown on the black economy and the introduction of a broad-based land tax as discussed below.

Replace Stamp Duty with a Broad-Based Land Tax

The federal government’s 2015 tax white paper made clear that stamp duty is a far less efficient tax than land tax. Stamp duty is also a far more volatile source of revenue for state governments. Land tax is a very progressive tax with the wealthiest Australians owning the most property. It is also the only type of wealth tax that can be reliably collected, with property unable to be moved out of the tax jurisdiction.

The ACT government has shown the way with a gradual transition from stamp duty to land tax. Land tax encourages empty nesters to downsize, freeing up homes for families that need more space. Allowing older property owners to accrue their land tax and pay it upon sale ensures that people are not forced out of their homes. Land tax levels should be consistent across owner-occupied and investment properties. However, vacant land zoned for residential purposes and properties vacant for more than half of the year should be subject to an additional 200% rate to encourage the available housing stock to be utilised. Studies using utility data suggest as much as 4.8% of the existing housing stock in Melbourne is vacant for extended periods. Incentivising the owners of these properties to list them for rent would lead to substantial downward pressure on rents.

End Financial Repression

Financial repression describes measures used by governments to hold down interest rates. This is effectively a tax on savers with the benefit transferred to borrowers. As the federal government is increasingly indebted after years of budget deficits it benefits from low interest rates. By setting the inflation target for the RBA too high, the federal government is unofficially taxing savers for its own benefit.

The global evidence on the effectiveness of ultra-low interest rates has become clearer now that eight years has passed since implementation. Ultra-low interest rates have not materially increased wages or consumer price inflation, or business investment. Ultra-low interest rates have inflated asset prices, including Australian housing. Lower interest rates reduce the monthly repayment required to repay a loan. Many buyers have used lower interest rates to increase the amount they borrow rather than borrowing the same amount and repaying it faster.

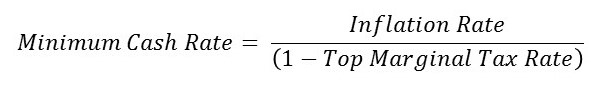

The federal government should amend the RBA’s current inflation target of 2-3%. It could be changed to keeping inflation below 3% or to target an inflation band of between -3% and 3%. To prevent financial repression the RBA should also be required to ensure that the cash rate allows all citizens to receive a positive after-tax real rate of return. This can be expressed as:

An independent RBA should embrace this rule as it will stop the federal government from using financial repression to deal with budget deficits.

Increase Mortgage Risk Weights for Riskier Mortgages and Implement Macro-Prudential Measures

APRA has recently increased the minimum mortgage risk weight for major banks to 25%. This is a positive step, but it still fails to push banks to hold more capital against higher risk mortgages. The reduction in bank capital levels for residential mortgages since the financial crisis and higher loan to value ratios (LVR) have allowed potential property buyers to borrow more with smaller deposits. For instance, at an 80% LVR a $100,000 deposit caps borrowing at $400,000. At a 95% LVR the same potential buyer could borrow up to $1,900,000. Higher loan amounts create an arms race; potential buyers use their higher borrowing limit to bid up property prices in a market with limited supply.

There are several ways that APRA can act to reduce speculative lending. For mortgage risk weights, the 25% minimum that APRA mandates could be subject to a 2.5% increase for every 1% the LVR increases beyond 70%. This implies a 70% LVR carries a 25% risk weight, an 80% LVR carries a 50% risk weight and a 90% LVR loan carries a 75% risk weight. Macro-prudential measures should include limiting owner-occupied lending to 90% LVR and investor lending to 75% LVR. APRA should also ban interest only loans where the LVR is above 75%. In the current environment with historically low interest rates and elevated property prices these measures would substantially reduce speculative lending and reduce the risk of banks becoming insolvent.

Encourage International Buyers to Purchase New Dwellings

If the primary focus of housing affordability is ensuring a sufficient supply of housing available for rent, governments should be encouraging the building of new dwellings that can be rented out. International investment should be channelled towards buying new dwellings, with substantial disincentives for purchasing existing properties. There should be no disincentives or impediments to purchasing new properties. When combined with the higher rates of land tax for leaving properties vacant these measures should substantially increase the number of properties available for rent, putting downward pressure on rent levels.

Ease Zoning Restrictions and Eliminate Development Levies

Several states have made substantial efforts in encouraging higher density development, especially near job centres and public transport hubs. When transparent systems for zoning and approvals exist, market forces have responded and the supply of residential property has increased. However, many local councils see developers as a potential goldmine slugging them with substantial development levies. These levies are often a way of shifting ongoing council expenses from existing rate payers to those purchasing new properties. Local councils should be funding their ongoing costs and community infrastructure costs from all ratepayers, rather than shifting costs to potential buyers and worsening housing affordability.

Enforce the Law When Unions Act Illegally

Illegal union activities have a subtle but substantial impact on housing affordability. Construction unions are regularly engaging in criminal activities in order to fill their own coffers and inflate the wages of their members. This is a deliberate tactic. Unions have found that the benefits they receive from illegal activities far outweigh the fines and compensation to those who have suffered economic loss in the unlikely event they are prosecuted. By blocking non-union members from working and shutting down building sites that refuse union demands building costs have increased well beyond inflation levels in recent years. Large scale construction in Australia is far more inefficient and expensive than in comparable markets overseas. The cost of apartment towers, which should be the most affordable type of housing, would be substantially reduced if free market forces were allowed to exist.

Conclusion

Australian politicians like to talk about housing affordability but have taken little action whilst rents and purchase prices become ever more unaffordable. The actions needed are obvious when basic research is undertaken. The federal government should reduce the migration intake, lower and equalise top income tax rates, and make changes to RBA and APRA policy. State governments should replace stamp duties with land taxes, encourage international investors to buy new properties and rent them out, ease zoning restrictions, eliminate developer levies and enforce the law when unions act illegally. If Australian politicians care about housing affordability and the quality of life of Australians, they will quit talking and start implementing the eight obvious and needed changes.

Written by Jonathan Rochford for Narrow Road Capital on November 29, 2016. Comments and criticisms are welcomed and can be sent to info@narrowroadcapital.com

1 topic