In theory there is no difference between theory and practice, in practice there is

How would you go about valuing a company or a house if you had no information or history on the price at which other similar companies/houses had sold? Like it or not, we are all influenced significantly by the behaviour of others. The marketplaces in which assets are bought and sold determine the prices and values on which investment returns and wealth are based, yet investors often spend little time understanding how they really work and what’s changing. The same is true of the marketplaces which determine crucial profit determinants such as commodity prices.

As passive investing (which we view as a cohort of investors seeking to piggy back on the research and price setting of others without paying for it) continues to eke market share from active funds, and ever larger superannuation funds and sovereign wealth funds (which are not terribly keen on price volatility and prices set by others) shun the listed marketplace in favour of private and unlisted assets, some of these marketplaces seem to be facing a few challenges.

Marketplaces are fascinating things

Shares, cars, houses, cryptocurrencies, payments systems, consumer goods; we enjoy, but take for granted the benefits of buying and selling quickly, easily and cheaply. As somewhat natural monopolies, given customers tend to like finding everything in one place, they are generally lucrative businesses to operate. Thriving marketplaces also find plenty of intermediaries looking to take a cut, as taking small amounts from a large quantity of transactions/people quickly adds up. In ‘Going Infinite’, Michael Lewis’ study of the FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) saga, Lewis describes the early career of SBF and colleagues at Jane Street Capital. That the highest salaries on offer to the best and brightest graduates are in writing code to arbitrage market pricing inefficiency should probably say enough about the size of profit pools. However, like many market makers, Jane Street describes its ‘higher purpose’ as making markets stronger by standing “ready to buy and sell a wide range of assets at competitive prices”.

In our view this could be better rephrased as being ready to buy and sell a wide range of assets as long as these can be quickly resold for a profit.

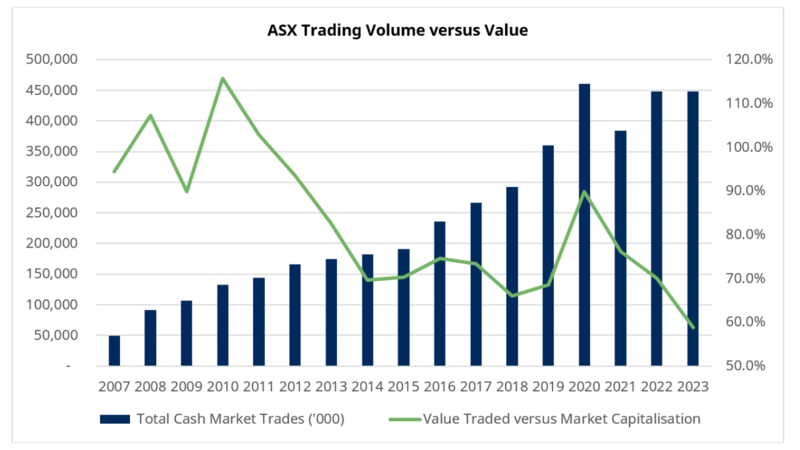

In our humble opinion, marketplace health is optimised by having a wide and deep pool of legitimate buyers and sellers, as the process of buying and selling is about finding a genuine owner for the asset, not an intermediary looking for a fast profit. Explicit costs such as fees are easy to see and measure, implicit costs in trading, excessive turnover, payments for flow, rebates etc., are harder to see and measure. Market makers and exchange operators invariably promote narrowing spreads as a key measure of market efficiency, a theory swallowed by numerous academics. In the past decade or two, stock exchanges have invested heavily in ensuring trades can be carried out in micro-seconds, an attribute that matters not one iota to any legitimate owner but matters a lot to players like Jane Street. Quickly loading countless small bids and offers into the screen allows the appearance of tight spreads and ‘efficient’ market pricing without any commensurate change in the number of genuine buyers and sellers. ASX data shows we have bathed in the glory of ever increasing trade numbers for many years now. Unfortunately the value traded has barely moved and the value traded relative to the reported market capitalisation of the ASX has fallen markedly. Price setting is relying on fewer legitimate buyers and sellers.

Popular wisdom suggests the rise of passive and more formulaic investment will create growing inefficiencies and more opportunity for active investors.

While possible, this theory requires the return of more efficient and reliable pricing and a deeper pool of well-informed buyers and sellers. Perhaps another area in which we’re not so sure theory will align with practice.

Source: ASX Annual Reports, Schroders

Determining how many passive free riders and high frequency trading intermediaries taking a cut between the trades of buyers and sellers a marketplace can bear (without perverting the ability to determine fair market prices by allowing genuine buyers and sellers to meet) is impossible to determine. Usually this point will be found after it breaks. ETFs and index funds package innumerable portfolios of stocks to cater to every investor whim. The underlying businesses to which listed markets should be providing capital and holding accountable for using that capital wisely have morphed into an industry focused on low explicit fees and satiating the appetite for exposure to a basket, theme or characteristic (technology, gold, quality, sustainability). Index providers extract egregious fees for arbitrarily deciding on some weights and maintaining a spreadsheet. We may be old fashioned, but healthy marketplaces are hugely valuable and should not be taken for granted. To borrow from Joni Mitchell; “you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone; they paved paradise and put up a parking lot”.

Raising hell

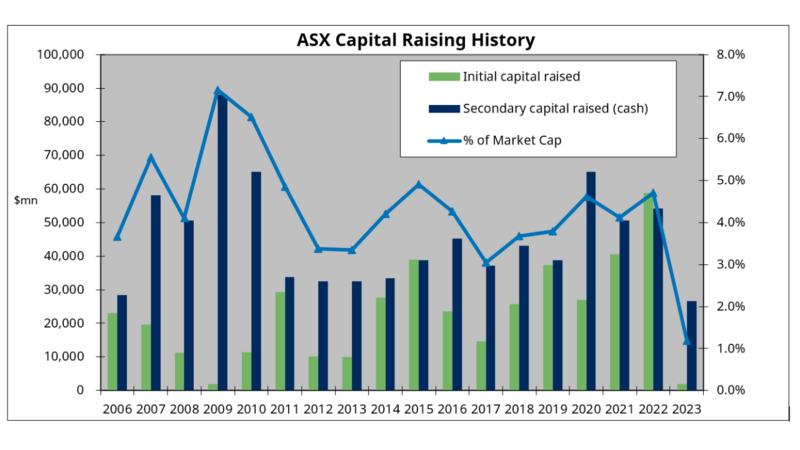

Another indicator of the extent to which listed markets are being shunned is the parlous state of capital raising. Initial capital raised on the ASX was as low as it’s been in many years in 2023. While the argument that unlisted private markets offer cheaper prices and better returns sounds good in theory, when you are a seller of a business you will generally try to find the buyer willing to pay the highest price. Collapsing capital raising activity suggests to us the sellers don’t like the prices on offer in listed markets. While theory might suggest unlisted assets earn an ‘illiquidity premium’ and provide extra returns as a result, when practice sees virtually no-one listing new businesses and quite a few moving into private hands at higher prices than prevailed in the listed environment (Origin Energy (ASX: ORG), InvoCare (ASX: IVC), Costa Group (ASX: CGC), United Malt Group (ASX: UMG)), practice suggests otherwise. Over-regulation, disclosure class actions and increasing scrutiny of overpaid executives and inept Boards are perhaps reasons for the declining appeal of the listed environment, however, sacrificing the enormous benefits and accountability which a healthy marketplace provides rather than solving the underlying problems seems an unlikely path to delivering higher returns.

Source: ASX Annual Reports, Schroders

Commodity confusion

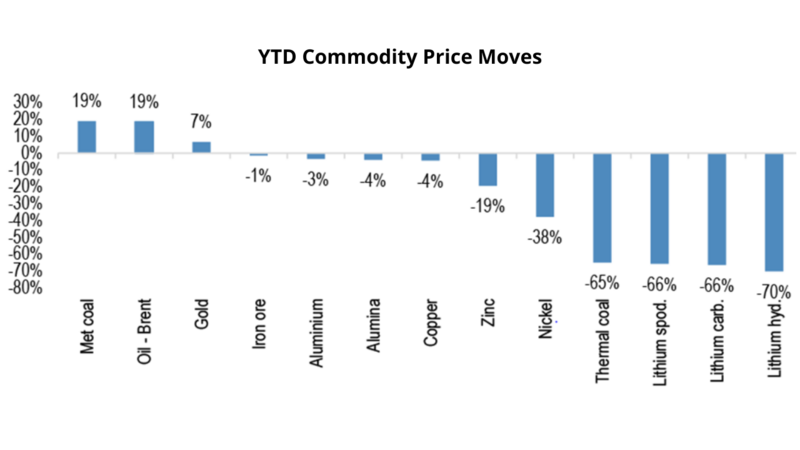

Equity markets are not the only place in which price formation is becoming questionable. YTD commodity price moves have perplexed many, us included. Despite obvious concerns in Chinese property markets and an expectation falling steel and iron demand would translate into falling iron ore prices, this hasn’t happened. BHP (ASX: BHP), Rio Tinto (ASX: RIO) and Fortescue (ASX: FMG) have continued to enjoy buoyant profits and the overflow from Gina Rinehart’s bank account has remained sufficient to shift from frustrating Albemarle’s takeover of Liontown Resources (ASX: LTR) to repeating the dose with SQM’s recent effort to take over Azure Minerals (ASX: AZS). Liontown shareholders saw the $3 bid morph into a $1.80 capital raising as Albemarle walked away and investors faced the reality of completing a mine still a year or two from production. All economic theory would suggest no-one would refuse a bid which factored extremely optimistic lithium pricing into the distant future. Practice saw a little more havoc.

Source: JP Morgan

If theory hasn’t gone to plan for the iron ore sceptics, life has been even tougher for the larger army of battery mineral bulls. October saw lithium prices and stocks crater (with the exception of Azure Minerals) while graphite exposures and Lynas (ASX: LYC) went the other way. Smooth upward sloping EV penetration charts which feature prominently in every supply and demand model are potentially becoming a touch bumpy. Sharp commodity price cycles which permeate every other commodity but weren’t supposed to apply to ‘future facing metals’, are not obliging. Ever confident in its ability to regulate its way to success, Europe is complaining about low priced and increasingly high quality Chinese EV imports. While subsidised infrastructure and power and failing to price pollution and safety to western standards is undoubtedly a factor in this equation, the high costs of regulation together with costly power and labour in Europe means supporting the European industry must come at a cost to consumers. Graphitisation to produce battery anodes and the messy and complex chemical processing which turns spodumene into the lithium used in cathodes are not quite as glamorous as the Tesla showroom. The arguments which Lynas has endured with the Malaysian government over its operating license aren’t because everyone wants to live near a rare earths cracking and leaching facility. These are necessary parts of the decarbonisation process, but they aren’t pretty. Additionally, as evidenced by the recent Chinese announcement of export controls on graphite (where China controls nearly 80% of natural graphite production, nearly 60% of synthetic graphite production and 90%+ of refined graphite and anode production), controlling the process is beyond the power of most countries without co-operation. Rising geopolitical tensions would suggest that looks optimistic. Tariffs merely force citizens to pay higher prices in creating the subsidies to support domestic production. Unlike the western world, China chooses to use more of its financial resources supporting production than consumption. The cost of bringing manufacturing back onshore is likely to be worthwhile, but significant. The engineering, manufacturing and construction capability which has been hollowed out will take many years to rebuild. We remain adamant the energy transition will transpire to be highly inflationary. It must also come at the cost of sacrificing consumption, a process which will have significant ramifications for businesses accustomed to ever growing consumption volumes.

Tell ‘em the price, Son!

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the US approach of handing out large wads of money to anyone keen to try their hand at a battery minerals plant is proving more enticing. That companies prefer to have taxpayers’ money handed to them via the government rather than competing for it in the free market should not come as revelation. That trying to lower capital and operating costs as a way to compete with products from lower cost countries, rather than asking consumers to voluntarily pay higher prices, should have a better chance of success ought not either. Price matters. When you have less money it matters more. Electric vehicles, solar panels, airline tickets and a raft of other items are not realistic options for the large part of the population for which cost of living pressures are already intense. Setting emission reduction targets, while admirable, is the easy bit. The gap between the theory on the presentation slides at COP28 and practice will be vast.

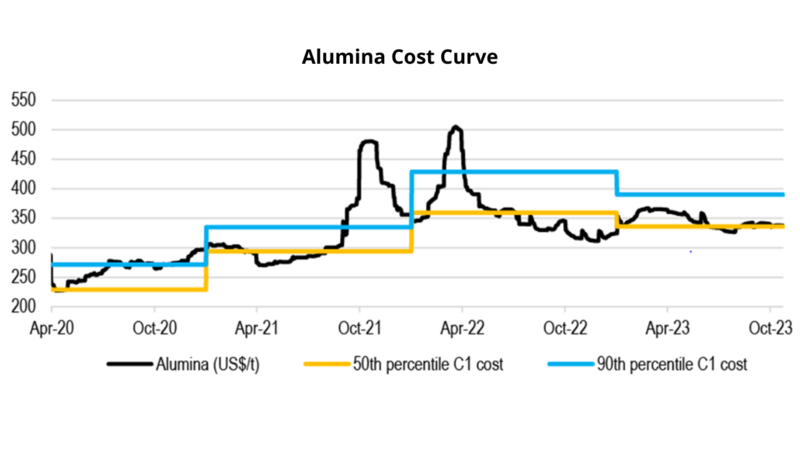

Chinese dependency and total lack of price transparency in areas such as graphite and rare earths, and the extent to which actions such as export bans can translate into abrupt changes in pricing, highlight the dangers of relying too much on history as a guide to the future. As governments continue to spend vastly more than they collect in tax revenue despite buoyant economic conditions, we’d expect an increasing likelihood of taxes, levies and interventions not currently anticipated in forecasts. The excessive profits to which shareholders have become accustomed in many sectors, technology, healthcare, selective commodities etc., which are often extrapolated into the distant future and seen as the result of strong market positions and pricing power, can equally be viewed as a source of future risk. When multiples are well above those of companies producing more pedestrian results, it seems to us these risks are not countenanced by many. Similarly, when profitability is low or non-existent, even for good quality assets, we often see risk skewed in the opposite direction. Our perspective sees alumina and aluminium markets falling firmly into this category at present. As pricing hovers around halfway through the cost curve, many producers are (by definition) making no money. When this prevails for an extended period of time (as it has), it is easy to believe nothing good will ever happen, while the share price charts and negative momentum have short sellers salivating. Valuations tend to expect rotten conditions to prevail indefinitely. It is also the time at which risk tends to become sharply skewed. If half the producers in the world are not making any money, historic cycles suggest conditions are unlikely to get a lot worse and are vastly more likely to get better.

Source: JP Morgan

Adapting to change is rarely easy, and pricing it into company valuations will always be subjective. The reaction of ResMed’s (ASX: RMD) share price and a raft of other businesses exposed to threats from Ozempic and other GLP-1 agonist medications is a case in point. The diabetes treatments, which by a stroke of good fortune have unintentionally become weight loss drugs, have forced investors into trying to rapidly assimilate a future in which obesity may abate as an issue. For countries in which the economic model involved fast food and consumer goods companies making a lot of money inducing obesity to then allow medical device and drug companies to make a lot of money treating obesity, this presents some challenges. Ignoring for a minute whether this was a good economic model in the first place, the pace and likelihood of this change can only be educated guesswork at present. There is minimal historic data which provides much assistance. After many calls and much investigation, we (I use this term loosely as the PhD in medicine of our healthcare analyst Sally Warneford has perhaps contributed more weight than the views of yours truly) have come to the view the share price move has overstated the likely impact. Notwithstanding her expertise, we can only deal in rough probabilities. The marketplace is allowing a myriad of investors to express their views of the likely impact in the company valuation. The future will never be a science and the future is what holds the value of a company.

Market Outlook

The apparent economic calm induced by more than a decade of ultra-low interest rates and pandemic induced government largesse is giving way to what we’d describe as more ‘normal’ conditions. The beliefs and theories popular with economists (which saw economies as systems which could be smoothed and guided by some wise and wonderful masters adeptly manipulating interest rates) are giving way to a more realistic view of the world which more closely resembles a game of ‘Whac A Mole’ in which suppressing one problem gives rise to a host of others.

In an environment where bonds have reverted to offering returns which are more akin to ‘normal’, it seems logical equities are enduring and will likely continue to endure similar adjustments. The vastly outsized gains which accrued to some sectors as investors happily priced the distant future as virtual certainty have only partially corrected in our view. The more traditionally priced segments of the market seem far less vulnerable. We may not always agree with how the marketplace assesses the future, and therein lies the opportunity. The marketplace at least offers us the opportunity to disagree. Theory says markets are efficient and it’s not worth trying to beat the crowd. In practice, crowds often do crazy things. To borrow from ‘The Castle’, one of my all-time favourites; “Dad…$450. …For jousting sticks?! Tell him he’s dreamin’! How much is a jousting stick worth, Dad? Couldn’t be more than $250. Depending on the condition”. We need to assess the condition.

11 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned