India's shift to organised business

India is a country where a significant movement is occurring from unorganised to organised business. This effectively means a shift from fragmented industries with low levels of regulation and informal methods to business where applying a set of rules, regulations, and processes are followed. Over the last five years the shift towards the organised economy has accelerated due to the changing ecosystem, heavily influenced by technology.

Unorganised business tends to be the domain of underdeveloped economy and thrives due to lack of a strong network and a low level of inclusiveness. Where simple requirements we take for granted in developed economies are not available such as electricity, roads, communication, and credit, then businesses are more likely to operate with smaller scale and rely on their localisation as a comparative advantage.

The reform of demonetisation was introduced in India in 2016, shifting the emphasis from a cash-based society towards a more credit oriented, digitised economy. Cutting the “black economy” to its knees had an initial impact of weakening India’s growth rate from 2017-2020 to 3-4% GDP growth (compared to 6-7% for the 20 years previous). However, the shift away from the cash economy led to a surge in the following (not neccessarily by intent):

- UPI Payments (rising from zero in 2016 to 134bn transactions daily by December 2020)

- Mobile Phones (now close to 1.2bn mobile phone and over 600m smart phones)

- Broadband connections (over 700m connections i.e., 50% internet penetration)

Secondly, came the reform of GST in 2017, which had the impact of removing state duties and taxes and therefore the differential taxes across India’s states and reduced logistical costs of transporting goods. This removes the comparative economic advantage localised businesses held relative to regional or Pan-India businesses. The scale benefits of having Pan-India business, lower taxes and logistical costs shift the balance towards large, organised players in every segment. Logistical costs are also dropping because of India’s slowly but surely improving infrastructure i.e., better roads, greater road coverage, improving railways, more flights and greater accessibility of flights and improving efficiency at ports.

This shift is seen across economies as they develop, industrialise and their ‘networking’ improves. In the context of India today networking includes better roads, mobile phone connectivity, broadband access, are more affordable access to flights and financial inclusion through a greater percentage of the population being banked (close to 80% now).

This network will create a substantial expansion in consumerism. Consumption in India has already grown from US$550bn in 2010 to US$1.6tn in 2019 and is likely to reach US$5tn by 2030 (growing at 10-12% p.a. over the period). This rising consumption pattern will be driven by an increasing share of affluent/elite households, urbanisation, nuclearisation of households and an increasing component of Gen-I (who are more prone to spending).

Businesses are likely to shift from local to regional and from regional to national as connectivity improves. This is likely to result in a shift from informal employment to finding formal work in retail outlets and chains. The growth of larger formats will make localised stores redundant, given higher productivity and scale, passing through to lower prices aka Walmart, Woolworths, Coles etc.

Opportunities for Organised Players

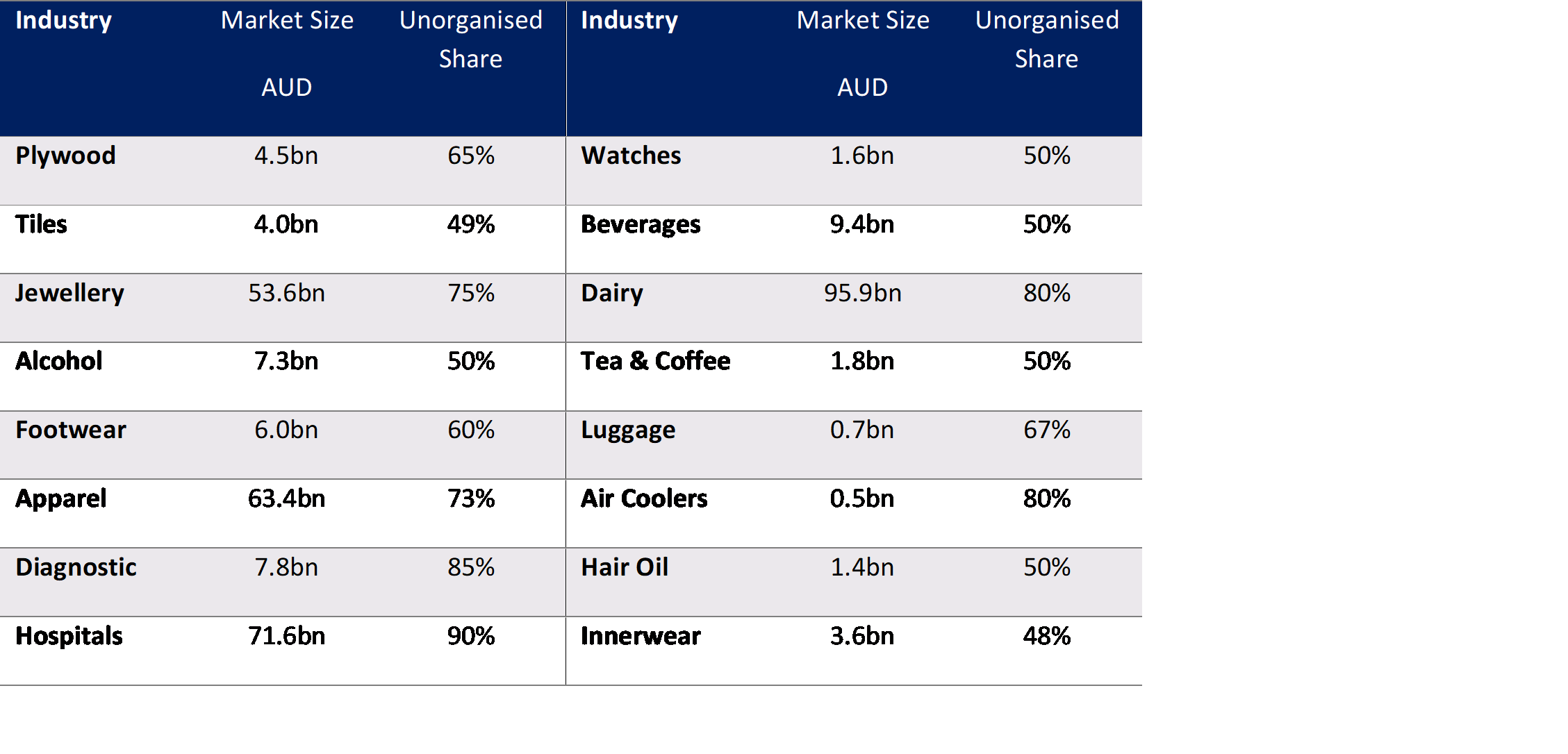

Dominant players across industries will thrive as the shift to organised formats and business occurs. An example is the retail industry, which is experiencing a significant move towards organised retail from India’s long time landscape of “kirana stores’ (single stores, convenience, localised). Yet while the growth in organised formats has been significant of late, it still only has 10% market share. Therefore, the shift to organised still has a long way to run and is more structural than cyclical over the next few decades. Better and more stable employment opportunities (in organised), lower prices and less tax arbitrage is likely to drive a greater share of the profit pie for the largest players in each segment. This should be good outcome for listed players with dominant market share across various industries.

3 topics