India’s thematics are great, but is it expensive?

Valuations provide investors with a margin-of-safety when investing. However, what appears cheap for one, may not be so cheap for another. The most commonly used measure, particularly where earnings are transparent and sustainable, is the Price-to-Earnings ratio i.e. what price am I paying for the future earnings potential of a business. It is important to highlight the word future here as a company’s price is generally driven more by its potential and less by its past.

The Indian economy’s GDP has been growing strongly at 7% p.a. or more over the last decade. This has created great expectations for its stock market given the opportunity set, particularly for companies operating within the local ecosystem. Yet Australian investors continue to remain shy when it comes to allocating to India, holding generally less than 0.5% of their portfolio’s in Indian domiciled equities. This hardly makes sense when considering India is likely to be ranked in the Top 3 economies globally by 2050.

Significant progress has been made over the past three years through economic reform, reduced corruption and increasing transparency. This coupled with the fundamental tailwinds of a significant and youthful population, improving monsoon climate and lower commodity prices leading to lower inflation bodes well for the economy.

However, one of the biggest bugbears for investors when commencing an allocation to India is valuation. Whilst investing in India should be considered from a long-term investment horizon, the starting point for an investor can provide a margin-of-safety or lack of one. Given the potential of a market like India, in conjunction with being considered a growth investment, it is highly likely that valuations in the short-term always remain elevated, particularly compared to other markets. For example, India has historically always traded at a premium to other markets given its earnings have been less cyclical and local companies are able to generate much higher return on equity.

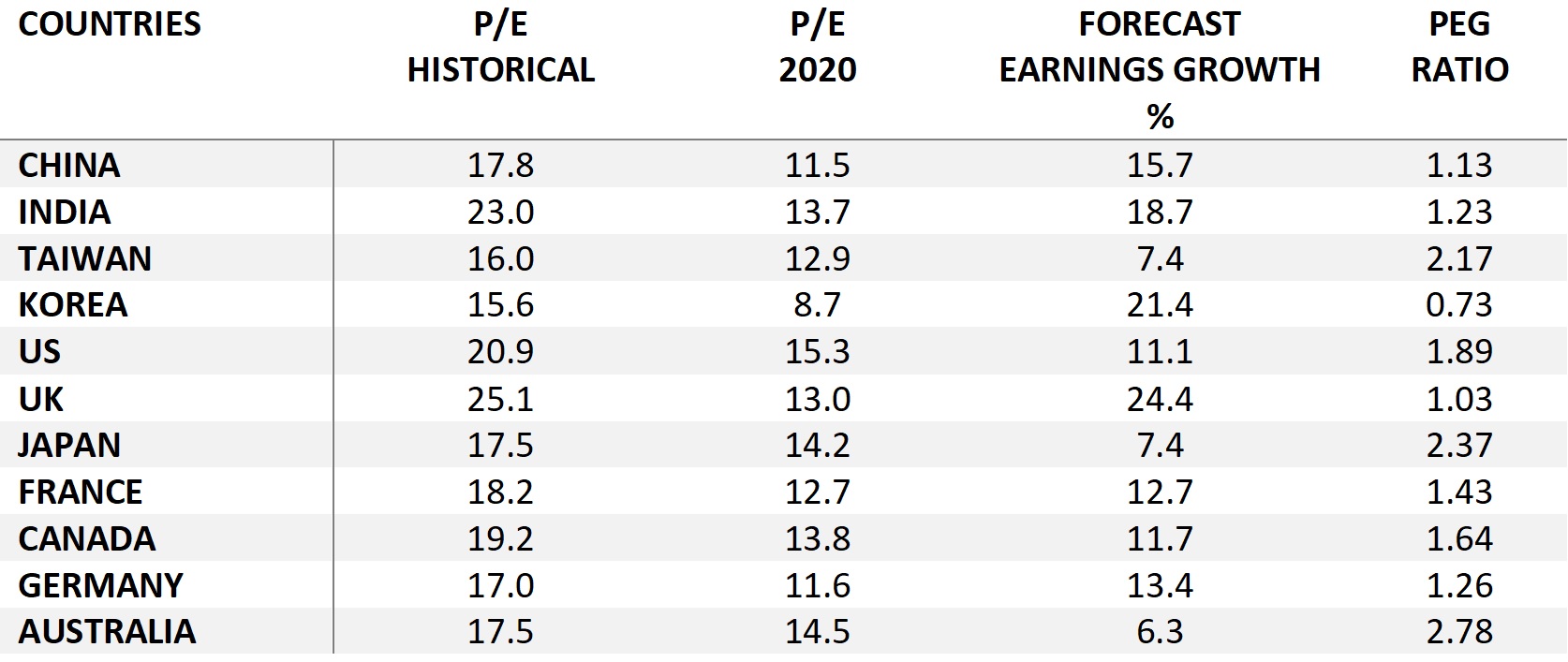

Source: Bloomberg, India Avenue

The 11 countries listed above provide almost 100% of the allocation for investors in their equity exposure across their superannuation funds. Most Balanced and Growth options (which tend to be default options) allocate between 50-100% to equities. Apart from heavy biases to Australia and the US, most other countries are less than 3% of their equity allocation.

Several countries listed in the table above look more attractive than India on a historical and one year forward P/E basis. As an investor, it is quite dependent on whether you are looking for a “cheap turnaround story” like South Korea, which requires you to buy into a significant upward shift in growth (from a low base given negative growth over the first seven years of this decade). In the UK earnings are expected to rebound strongly after falling into a hole. Likewise, Germany, France, Taiwan and China promise improving earnings growth, compared to their past experiences over this decade so far.

What India offers is much cheaper valuations three years from now. Consider this for an equity market where companies have still managed to grow earnings at 7.2% over the decade despite being in a “weak patch”. During the early part of the decade the economy had stalled, given high inflation and a large current account deficit, the banking system crippled by non-performing assets and corporates stalling their investment programs.

Prime Minister Modi’s significant and impactful economic reforms and strong fundamental tailwinds are making India a strategic long-term investment consideration with the potential for rising earnings growth from here. This is a far cry from most economies like Australia, which are set to battle harder times than experienced over the past 20 years. Most investors have significant allocations to Australia and the US in their superannuation portfolios, whilst they appear the least attractive on a PEG ratio basis! India’s PEG ratio looks attractive relative to most economies.

Twelve months ago, India was considered expensive, as it was three years ago and five years ago. In 2017 returns have been around 20% vs Australia's 0%. The point here is that valuations need to be considered in the right context rather than simply comparing them on an absolute basis. Buying cheap valuation with little or no growth seems redundant going forward.

5 topics