Interest rate shock just around the corner

The Reserve Bank of Australia has a massive trick up its sleeve. The potency of this gambit is still very much underappreciated. In its latest financial stability review, the RBA published a chart on the share of fixed-rate mortgages in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the UK and the US.

NZ and the US are sitting at or above 90 per cent of all home loans. The UK is north of 80 per cent. Canada is just shy of 70 per cent. The construction of the Aussie mortgage market is, by way of contrast, radically different. Historically, less than 20 per cent of all loans have been fixed.

As a result of the RBA generously lending $188 billion of three-year fixed-rate loans to the banking system at an annual cost of between 0.1 and 0.25 per cent during the pandemic, the share of fixed-rate mortgages surged to almost 40 per cent of the stock.

The RBA estimates that around 23 per cent of all Aussie home loans – worth almost $500 billion worth – are fixed rate and will switch to variable rate by the end of 2023.

“Based on current market pricing for the cash rate and assuming full pass-through to variable mortgage rates, most fixed-rate borrowers with loans expiring in 2023 will face discrete increases in their interest rates of 3–4 percentage points when they roll over to variable rates, depending on their current rate and the timing of their fixed loan term expiry,” the RBA warns.

Martin Place has further revealed that if its cash rate were to increase by 3.5 percentage points in total, “almost 60 per cent of borrowers with fixed-rate loans would face an increase in their minimum payments of at least 40 per cent when they expire”.

This is an interest rate shock that was never meant to happen. Before October 2021, banks were only required by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority to apply a mortgage repayment test that involved using an interest rate that was just 2.5 percentage points above the actual product rate. The RBA has already increased its target cash rate by more than this (ie, 2.85 percentage points). Market pricing expects the totality of the RBA’s interest rate increases to reach 3.75 percentage points.

In October 2021, APRA prudently front-ran the RBA, and jacked up the minimum repayment test buffer for banks to 3 percentage points. (Most non-bank lenders still use a miserly 2.5 percentage point buffer.) This will, however, prove to be inadequate to cope with the circa 350-400 basis point interest rate shock that the RBA will inflict on borrowers.

Cheap loans

Put differently, there will be many borrowers who took out ultra-cheap home loans in 2020 and 2021 on the presumption that the RBA would not lift rates until after 2024 who will now face mortgage rates that are 40 per cent more than the maximum their lender thought they would ever have to service during their lifetimes (ie, via APRA’s stress test).

Most of the fixed-rate loans taken out in 2020 and 2021 were struck at mortgage rates of between 1.75 and 2.25 per cent. As more than one in five Aussie home loans have their fixed rates switch to variable rate by the end of 2023, the interest rates paid by these borrowers will more than double to 5-6 per cent.

In contrast to most other nations where most loans are long-term fixed-rate products, the pass-through of monetary policy in Australia directly hits almost every single borrower in the short term. This is also why the RBA’s rate changes have a much bigger and more immediate impact on our housing market compared to peers overseas.

One key question that has been weighing on the RBA is how big a deal this record rise in the cost of capital will be for consumers’ free cash flow (or their disposable income). This is crucial for the outlook given that consumer spending accounts for about 50 per cent of total economic growth.

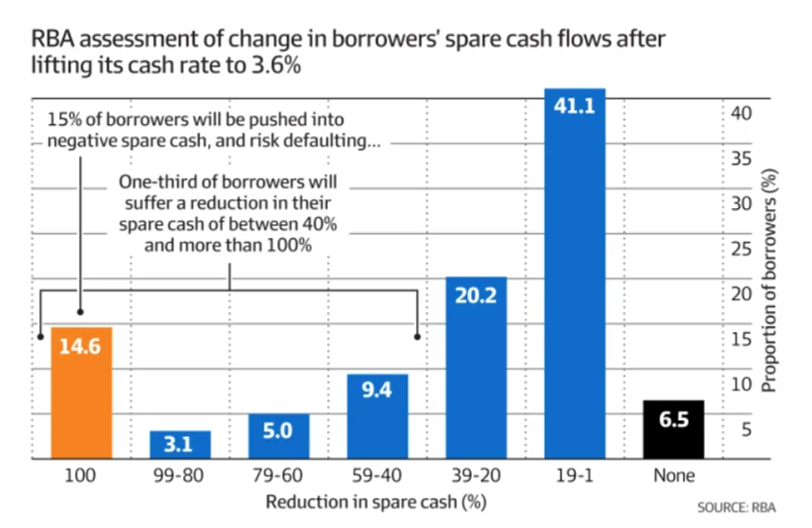

Using the RBA’s data on residential mortgage-backed securities, it finds that more than 52 per cent of all borrowers will see their “spare cash” decline by between 20 per cent and more than 100 per cent, assuming its target cash rate climbs to 3.6 per cent.

Spare cash is defined by the RBA as the income the borrower has left over after meeting mortgage repayments and “essential living expenses”.

A staggering 15 per cent of all borrowers will have their spare cash turn negative in the RBA’s base case. That means they are at a very serious risk of defaulting on their loan repayments.

A total of 23 per cent of all borrowers – or more than one in five – will see their spare cash shrink by between 60 per cent and more than 100 per cent.

Almost one-third of borrowers will have their free cash reduced by between 40 per cent and over 100 per cent.

This presages a huge reduction in household spending if the RBA gets to a 3.6 per cent cash rate next year. Note that this is actually slightly below current market pricing, which anticipates a higher 3.85 per cent terminal cash rate by mid-2023.

Slower rate rises

The enormous reduction in Aussie households’ spare cash is almost certainly one reason why the RBA has been comfortable slowing the pace of its interest rate increases and signalling that it will soon pause to take stock of the cumulative effect of these changes.

Given the multi-month lags between the RBA raising its target cash rate and lenders actually passing through these increases to borrowers, the transmission to actual consumer spending, demand and price pressures just takes time. And it will take many months more for these shifts in household behaviour to be evident in the official economic data, which is reported on a lagged monthly or quarterly basis.

Households clearly sense that their cash flows are about to get trashed. This is borne out in the consumer confidence data, which is worse than the levels recorded during the GFC. And it is also reflected in the real-time daily house price indices reported by CoreLogic.

National house prices are falling at a record 14 per cent annual rate based on the last three months of data from CoreLogic, with a total drawdown of 7.4 per cent since the five capital city index’s May 2022 high watermark.

The epicentre of what will become the biggest housing crash in modern Aussie history has shifted from Sydney to Brisbane, where prices are falling at an incredible 20.3 per cent annual rate (Brisbane values have already shrunk 7.7 per cent peak-to-trough thus far).

Sydney dwelling values have fallen furthest, plunging a massive 11.1 per cent since their peak in absolute terms. Sadly for homeowners, Sydney dwelling values continue to decline at a 17 per cent annual rate based on the past three months of price moves.

This is a secondary channel through which monetary policy affects behaviour – via a huge negative wealth effect.

Originally published in the AFR here.

2 topics