Interest rates: lower and sooner?

Is inflation re-accelerating?

Will rising oil prices push central banks to raise rates further?

Is a recession still likely?

And are markets overvalued?

These are the meaty questions Greg Canavan and I grappled with this episode.

What’s not priced in?

Recession remains a risk the market continues to under-price, at its peril.

Oh, and we also talked about the US Open. With Djokovic’s victory, is the GOAT debate now settled?

Can inflation re-accelerate on rising energy prices?

Can rising energy prices stoke and re-accelerate inflation?

It is a worry the major press is articulating prominently right now.

Last Wednesday, the Wall Street Journal ran a headline stating ‘US inflation accelerated in August as gasoline prices jumped’.

And last Friday, the Financial Times summed up the European Central Bank’s decision to raise interest rates to a historic high in this way:

‘While eurozone inflation has dropped from a peak of 10.6 per cent last year to 5.3 per cent in August, the recent rebound in oil prices has raised concerns that the disinflation process will be bumpy.’

But can rising energy prices really stoke inflation anew?

For Greg, it’s unlikely.

Companies may struggle to pass on higher energy costs to consumers if the end demand isn’t there.

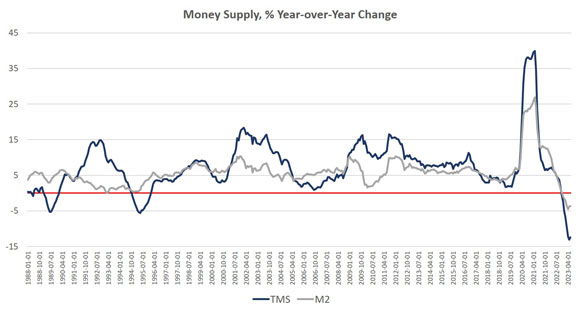

Raising prices has been easy over the past two years because of a huge surge in money supply.

But that’s dwindling fast … along with household savings and discretionary spending appetite.

What’s not priced in: recession

The current mood in the US is seemingly buoyant.

A monthly Bank of America survey found six out of 10 fund managers who responded said the ‘Fed is done’ hiking rates.

In July, nine out of 10 fund managers surveyed were saying the ‘Fed is not done’.

That’s a quick turnaround.

US firms are also mentioning the R word less and less — recession.

FactSet trawled through earnings calls for S&P 500 companies and found only 62 companies cited ‘recession’ on earnings calls from 15 June through the end of August.

That’s down from 113 during the previous reporting period and well down on 238 in the US summer of 2022.

The mood is similarly optimistic in Australia.

Australia’s big banks have told Treasurer Chalmers last week a ‘soft landing’ for the economy is now the likely outcome.

A recession is not.

Westpac chief executive Peter King said:

‘At the macro level, things are a bit softish, but a soft landing is looking quite plausible. The key will be employment and people having jobs.’

And National Australia Bank chief Ross McEwan concurred:

‘We just don’t see that there will be a recession in Australia. It’s just quiet at the moment.

But as Greg quipped, CEOs of big banks are rarely caught predicting a recession. It’s just not their MO.

Greg then broke things down into a risk-reward probability analysis.

According to the latest consensus estimates, US 2024 earnings are set to grow 12% over 2023.

On forward estimates, the benchmark S&P 500 trades on a P/E multiple of 18.75.

That’s a tad higher than its long-term historic average and represents an earnings yield of 5.33%.

Yet the yield on a 10-Year US Treasury bond is around 4.3%.

In Greg’s words:

'Based on reasonably rosy forward earnings estimates, the stock market doesn’t offer much additional reward over ‘risk-free’ bonds.’

How can this be resolved in favour of the stock market?

Either earnings increase faster than already expected, or bond yields fall sharply.

Which is more likely given the macroeconomic slowdown?

With monetary tightening still winding its laggard way through the economy, better than expected earnings growth is just a low probability scenario.

Falling bond yields are more probable.

However, the reason behind falling bond yields is the real worry.

Plummeting bond yields imply a weak economy — and possibly even a recessionary one.

That’s obviously not good for company earnings … and stocks.

Greg than quoted research from economist Dave Rosenberg.

Rosenberg thinks a US recession is in the offing in the next quarter or two, rejecting a ‘soft landing’ thesis.

In his latest research note, Rosenberg wrote:

‘And for those who don’t see a recession, just remember the traditional lag from the Fed’s first volley to the time of the recession historically was not 22 minutes, 22 hours, 22 days, or 22 weeks. More like 22 months. That puts Q4 of this year or Q1 of next year in play.

‘All “soft landings,” and they can easily last a year (think 1989, 2000, 2007), are bridges from the expansion to the contraction phase of the cycle. They are a transition period. And they are not permanent.

‘Either the economy somehow reaccelerates (with looming fiscal tightening and the lagged impact from the Fed in terms of what still lies ahead makes that unlikely), or it downshifts into recession.’

For Rosenberg, soft landings ‘don’t hang around to perpetuity’.

The next six months will be telling.

What’s not priced: unit labour costs to prop up services inflation

I mentioned NAB’s Ross McEwan earlier.

While the NAB boss doesn’t see a recession in Australia coming, he did say ‘we need a lot more productivity’.

He isn’t the only one.

(I’m not talking about viral phenomenon Tim Gunter.)

Outgoing RBA governor Philip Lowe has been quietly warning about productivity for months and made it a key topic in his final speech as RBA’s honcho.

In countless monthly statements following the Reserve Bank’s cash rate decision, Philip Lowe insisted that ‘wages growth has picked up over the past year but is still consistent with the inflation target, provided that productivity growth picks up.’

Well, productivity growth is not picking up but dropping.

While we worked 6.8% more hours this year than last year, labour productivity fell 3.2% in annual terms.

GDP per hour worked fell 2% in the June quarter and is down 3.6% year on year.

The big thing for me was labour unit costs.

Labour unit costs measure wages growth in relation to productivity. Higher labour unit costs imply wages are rising without a related lift in productivity.

Real unit labour costs rose a substantial 3.2% in the quarter and are up 5.8% for the year!

Why is this a big deal?

Anaemic productivity is bad news for labour unit costs and, by extension, services inflation.

As Lowe said back in June, there is a ‘close relationship between inflation and the rate of growth in unit labour costs.’

Here’s the kicker:

‘Over the entire inflation targeting period, the cumulative increase in the CPI has closely matched that in unit labour costs, although there have been periods of divergence.’

And in May, Philip Lowe faced a Senate committee and said this:

‘If unit labour cost growth is 3.5% to 4%, then it’s hard to have 2.5% inflation. So that’s the issue that I’m drawing attention to.

‘The best solution to this is a lift in productivity growth. If we’re going to have 2.5% inflation, we cannot have unit labour costs persistently growing at 3.5 to 4%. We have to have labour cost growth starting with a ‘2’.’

Current labour cost growth does not start with a 2.

Later in the session, Lowe said:

‘For inflation to average 2½ per cent, we would expect that, on average, wages increase at the rate of productivity growth plus 2½ per cent.

‘Given that the distribution of national income between wages and profits can and does vary, this relationship is not a hard and fast rule, but it is a reasonable benchmark.’

Let’s try a little napkin maths.

The latest ABS June quarter data dump showed GDP per hour worked fell 3.6% year on year.

So, for inflation to average 2.5%, given productivity fell 3.6%, wages had to decline 1.1%.

Last month, ABS’s wage price index showed annual wages growth in the June quarter rose 3.6%.

For inflation to really come down, either productivity miraculously picks up … or Tim Gurner gets his wish.

Interest rates — lower and sooner?

Consensus is now firming that interest rates will stay ‘higher for longer’.

But Greg thinks when consensus congeals in markets, it’s time to listen to your inner contrarian.

As we discussed at length in the episode, the mantra of ‘higher for longer’ may be superseded by ‘lower and sooner’.

What’s not priced in?

As household savings dissipate and consumer demand falls, central banks could end up cutting more than expected in 2024 as inflation follows the money supply down.

That won’t be bullish for markets.

Enjoy the episode!

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned

.png)

.png)