Investing in fixed income when rates are rising

Economic growth in most countries continues to print at or above trend. The slack in economies created during the GFC and its aftershocks (Europe in 2011, emerging economies in 2015) is finally being eliminated. Whereas in each of the last few years there was considerable uncertainty about whether central banks would be able to end Quantitative Easing (QE) or raise rates, it has become clearer now that they can, and will. Here we discuss five key issues for fixed income investors as rates rise.

How high will bond yields go?

The elimination of slack in economies – best exemplified by falling unemployment starting to spur higher wages – suggests economies are ‘normalising’. What this means is that now, finally, stronger growth should be followed by higher inflation. This, in turn, should see a more symmetric response by central banks to changes in growth and inflation.

The US has clearly been the leader. First the Fed stopped buying bonds and over the last 18 months it has been steadily lifting the cash rate. Canada and the UK have lifted rates from emergency settings. The ECB has mapped out a path for the wind-down of bond buying. Australia’s RBA is indicating the next move in rates is up.

How high yields go in this environment depends on several things:

Firstly, if more countries begin lifting rates then the global effect is likely to be larger. Although growth across economies and forward-looking business sentiment is reasonably synchronised, most countries are lagged (in their elimination of output gaps) relative to the US and are therefore likely to be delayed in hiking. This suggests differences between countries will play out in other ways – for example via currency moves – rather than through universally higher rates.

Secondly, will we see inflation accelerate? We don’t think markets are priced well for the likelihood that inflation picks up more than expected. In the US, for example, we think inflation could ‘overshoot’ into the 2.5-3% zone. While this will cause reassessment of the path for policy and put upwards pressure on bond yields, we aren’t, however, expecting a substantial acceleration in inflation to much higher levels.

Finally, while the cycle is looking reasonably bright, structural issues - high debt load, aging demographics, and the disinflationary effects of globalisation and technology - are likely to mean longer term yield rises will be limited.

Is the traditional relationship between bonds and equities changing?

A big concern of many investors is that as bond yields rise, riskier assets that have benefited from stimulatory monetary policy will also underperform. The evidence is mixed. Correlations between government bonds and riskier asset returns have mostly been negative over the last several years in spite of QE. Additionally, looking at historical experience, higher rates have usually been accompanied by good returns from cyclically-sensitive assets, until policy starts to become too restrictive.

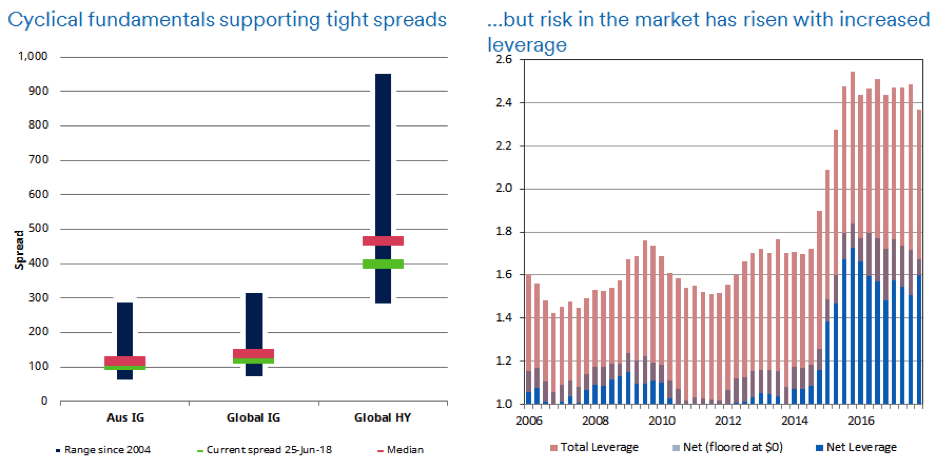

Our view on credit is that we are in the late cycle phase where it’s best to be exposed to the higher quality segments of the credit markets. Credit risk premium usually performs well in the early phase of a tightening cycle as the economy and corporate profits continue to provide a positive back drop. Currently corporate health remains reasonable and defaults are low although leverage remains elevated and valuations are on the expensive side.

Source: Schroders, Barclays Global Aggregate (LHS), Deutsche Bank (RHS). Data in RHS chart indicates leverage in the US IG market

As the tighter monetary conditions start to bite we expect to see widening pressure on credit spreads. It’s then that we have a reset of risk premium which leads to the opportunity to set portfolios for the next phase of the credit cycle.

One area of concern could potentially be in bond proxies eg REITS or alternative assets like infrastructure debt that are heavily reliant on bond yields to drive valuations and very sensitive to rate changes.

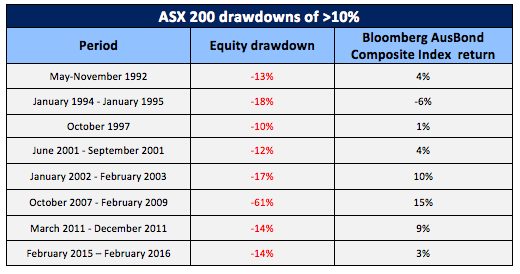

While the direction of correlations is ambiguous, for us the more important point to remember is the diversification benefit of owning fixed income (duration) typically comes when needed the most during periods of risk aversion and stress environments.

Table: Bond returns during worst 10 drawdowns of the ASX200

Source: Schroders / Bloomberg. ASX total returns and Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+Yr Index returns since 1992

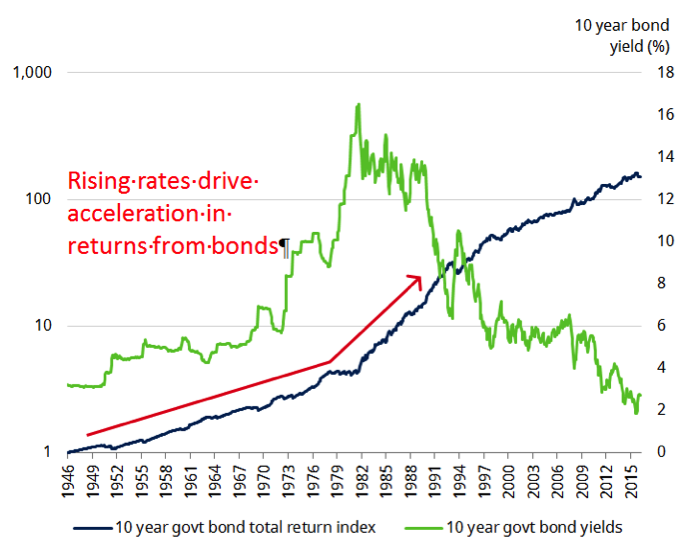

Rising rates make fixed income more valuable

A lot of people spend a lot of time worrying about changes in yield levels and the impact on short term fixed income returns. However, the maths of bonds is that over the long term, the level of income is much more important for returns than are changes in yields. In other words, a rise in yields in the short term, while sometimes a little painful, sets up better long term performance driven by higher yield (income) levels.

10 year Australian government bond returns and yields over past 70 years

Source: Schroders, Bloomberg

Fixed income’s value in a broader portfolio context is also improving. Because bonds have to a degree already repriced but expensive riskier assets have not, fixed income is starting to look appealing. For example, our medium term return forecasts expect a higher return now from US government bonds than from US equities.

Additionally, although the focus is on the upside in the cycle, we’ve got to be cognisant of risks to the downside. Our modelling suggests that US recession could come as early as the end of 2019. Higher yields now build in better recession protection for later.

If we’re right about structural forces limiting the upside in yields, and the end of the (at least US) cycle is looming, then there’s also a reasonable chance we’ve seen the worst of the yield move already.

How much fixed income should I have?

This is not an easy question to answer because it depends on a number of things, including your objectives, timeframe and risk appetite, and the other risks you have in your portfolio.

We strongly believe fixed income should be part of broader portfolios because of the defensive nature of the asset and diversification benefits. For the latter you need duration which may feel uncomfortable at the moment, however as discussed above we think investors should be thinking about moving to embrace more rather than less.

What style of fixed income, and how it’s managed, is just as important

A key part of answering ‘how much fixed income’ is what style of fixed income do you want (in the context of your broader portfolio) and how it is managed.

Fixed income comes in many shades, including the recent proliferation of absolute return offerings. If you want your fixed income allocation to help provide diversification against equity risk, then you’ll need a more traditional duration-based solution. If you want your allocation to deliver a higher return but come with less bond/duration beta, then an absolute return offering may be appropriate subject to other risks in your portfolio. A bit of each is fine so long as you understand their different roles in your portfolio.

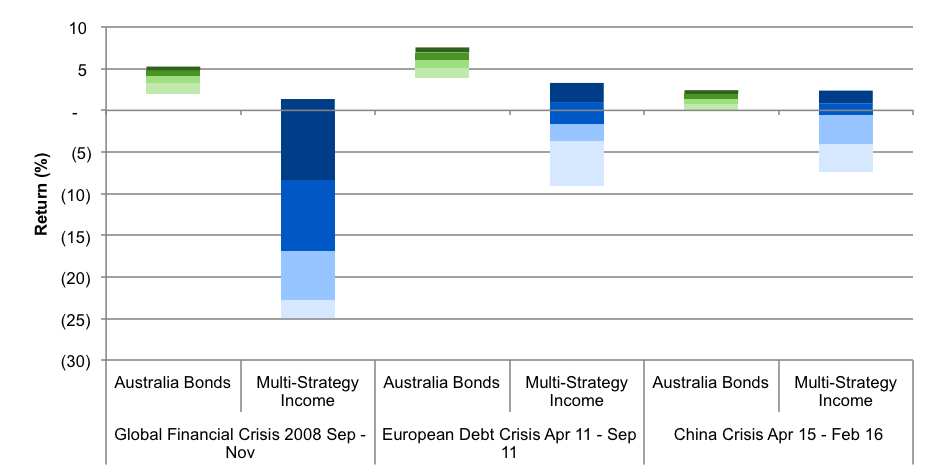

The diversity of absolute return fixed income offerings, and illustrated by the Morningstar Multi-Strategy Income universe in the chart below, also results in a greater performance dispersion between strategies and a need to understand which ‘levers’ managers use to generate their absolute returns.

Range of Performance for fixed income approaches in stress environments

Source: Morningstar Direct. Chart shows the 5, 25, 50, 75 and 95 percentile range of performance of funds in the Morningstar Australia Multi-Strategy Income and Bonds – Australia categories net of fees. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance

Finally, we believe active management is crucial. We think the ‘normalisation’ of markets is likely to be volatile and managing the transition/path will be vital. Within duration-based portfolios this means active management of the duration position/the portfolio’s exposure to interest rates, in particular, as we navigate through rising rates.

Bond benchmarks such as the Bloomberg AusBond Composite Index, are now no longer good barometers of risk due to their lack of diversity, dominated by government issuers and lengthening duration.

Equally, management of the balance of risks within absolute return portfolios is critical to ensure returns can remain positive and volatility (include losses) minimised.

Find out more

You can access more insights from Schroders Australia here.

--

Disclaimer: Opinions, estimates and projections in this article constitute the current judgement of the author as of the date of this article. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Schroder Investment Management Australia Limited, ABN 22 000 443 274, AFS Licence 226473 ("Schroders") or any member of the Schroders Group and are subject to change without notice.

In preparing this document, we have relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources or which was otherwise reviewed by us.

Schroders does not give any warranty as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of information which is contained in this article. Except insofar as liability under any statute cannot be excluded, Schroders and its directors, employees, consultants or any company in the Schroders Group do not accept any liability (whether arising in contract, in tort or negligence or otherwise) for any error or omission in this article or for any resulting loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise) suffered by the recipient of this article or any other person.

This document does not contain, and should not be relied on as containing any investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. You should note that past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

4 topics

1 contributor mentioned