Investing wisdom from the latest Buffett letter

Over the weekend, Berkshire Hathaway released Warren Buffett’s annual letter to investors. There’s little doubt in my mind that this is the single most widely read piece of financial content in the world each year. This is now the seventh time I’ve read it at release, and roughly the 40th of his letters that I’ve read. After years of reading Buffett’s wisdom, the thing that stands out to me above all else is the consistency of his messaging. Probably no other investor in history has been able to maintain such a consistent message over such a long time. This quote was featured in the most recent letter, but wouldn’t have looked out of place in any one of the ~55 annual letters he’s penned:

“(Our goal is to) buy ably-managed businesses, in whole or part, that possess favorable and durable economic characteristics. We also need to make these purchases at sensible prices.”

As is tradition, here I’ll extract, summarize, and occasionally editorialize some of the most interesting pieces of wisdom and insights from the world’s most famous investor.

Accounting for an important change

For the first time in nearly three decades that the letter hasn’t opened with his note about the annual change in Berkshire’s book value – instead it now opens with an explanation of the (silly) new accounting practices that force fluctuations in a share portfolio to be reflected in the company’s bottom line. As Buffett appropriately points out, an accounting rule that causes net earnings to fluctuate by billions of dollars in a day is hardly helpful.

“Wide swings in our quarterly GAAP earnings will inevitably continue. That’s because our huge equity portfolio – valued at nearly $173 billion at the end of 2018 – will often experience one-day price fluctuations of $2 billion or more, all of which the new rule says must be dropped immediately to our bottom line. Indeed, in the fourth quarter, a period of high volatility in stock prices, we experienced several days with a “profit” or “loss” of more than $4 billion. Our advice? Focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety.”

No change of tune though…

While some have criticised Buffett’s displeasure with the new accounting rules, suggesting it hypocritical given his views on adjusting earnings, it’s clear that his views here haven’t changed:

“That brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs. Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of all-too-real costs.

I think the distinction here stems back to true economic value. Buffett has always been happy to accept depreciation costs on real assets as part of earnings but has criticised the amortisation of intangibles as a non-economic cost. His more recent criticisms seem to be consistent with this.

“For example, managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business – Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.” Abe would have felt lonely on Wall Street.”

Sky high valuations in the private market

One of the less talked about effects of Quantitative Easing (QE) was to push an enormous amount of money into private equity. Private Equity and Venture Capital funds around the world are cashed up with investor funds, and many of them have huge undrawn debt facilities to ‘compliment’ this. This has resulted in hundreds of “unicorns” (unlisted, venture-backed companies with $1B+ valuations) and the proliferation of co-working spaces. This led WeWork CEO, Adam Nuemann to tell Forbes that “Our valuation and size today are much more based on our energy and spirituality than it is on a multiple of revenue."

Clearly, Buffett is observing similar phenomena, making it clear that he’s investing far more in public equities than private businesses in recent years.

“Let me remind you of our prime goal in the deployment of your capital: to buy ably-managed businesses, in whole or part, that possess favorable and durable economic characteristics. We also need to make these purchases at sensible prices.

Sometimes we can buy control of companies that meet our tests. Far more often, we find the attributes we seek in publicly-traded businesses, in which we normally acquire a 5% to 10% interest. Our two-pronged approach to huge-scale capital allocation is rare in corporate America and, at times, gives us an important advantage.

In recent years, the sensible course for us to follow has been clear: Many stocks have offered far more for our money than we could obtain by purchasing businesses in their entirety. That disparity led us to buy about $43 billion of marketable equities last year, while selling only $19 billion. Charlie and I believe the companies in which we invested offered excellent value, far exceeding that available in takeover transactions…

…in the years ahead, we hope to move much of our excess liquidity into businesses that Berkshire will permanently own. The immediate prospects for that, however, are not good: Prices are sky-high for businesses possessing decent long-term prospects.”

Don’t pick up pennies in front of steamrollers – the dangers of debt

More than 10 years on from the financial crisis, some may have forgotten the state of capital markets during that time. In fact, many currently active investors would’ve been still in high school at the time! In times of crisis, capital markets can completely seize up and push debt-laden companies over the edge. These lessons should be familiar to those who held Babcock and Brown, Credit Corp, or RAMS Home Loans leading into the crisis. (Here’s a flashback to one of the worst days of the crisis for anyone who wants a refresher.)

“We use debt sparingly. Many managers, it should be noted, will disagree with this policy, arguing that significant debt juices the returns for equity owners. And these more venturesome CEOs will be right most of the time.

At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes and debt becomes financially fatal. A Russian roulette equation – usually win, occasionally die – may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside. But that strategy would be madness for Berkshire. Rational people don’t risk what they have and need for what they don’t have and don’t need.”

Purchase of Apple doesn’t look so rotten

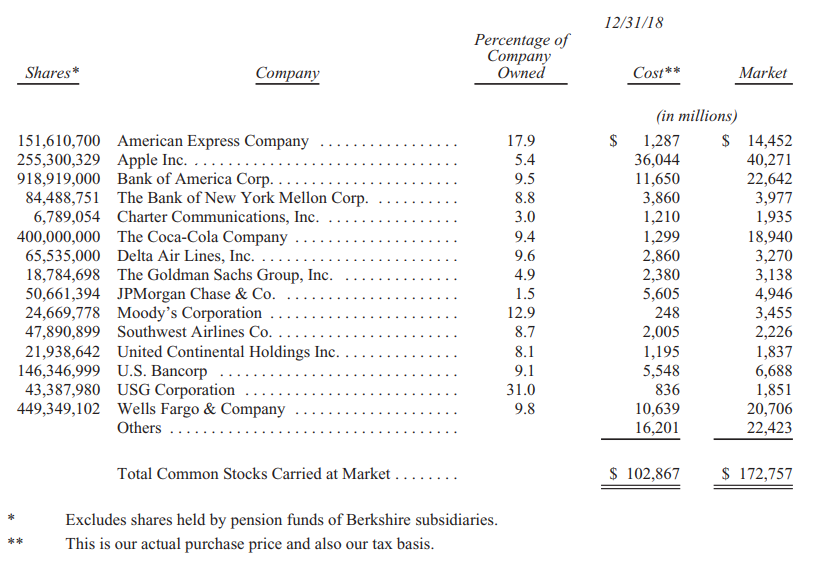

Despite Apple’s falling share price and the criticisms levelled at the company, Buffett’s purchase of Apple shares is still comfortably in the black. Berkshire’s massive $36B stake has grown to over $40B – and it’s rallied another 9.6% in the two months since the end of Berkshire’s reporting period. Not a bad effort considering the stock is still ~25% off its highs.

About those profits from the equity portfolio…

There’s a common saying among professional investors that if you’re getting six out of 10 investments right, you’re doing pretty well (for venture capital it’s more like one out of 10). The implication being that the gains on the upside should be more than large enough to offset any losses on the downside.

Despite the difficulties of consistently getting it right, of the top 15 holdings in Berkshire’s holdings, 14 of them are currently worth more than the company originally paid for them. JPMorgan Chase is the sole entry in the “red” column. The company’s smaller holdings also add up to a net positive, and even the Kraft Heinz holding (not part of the equity portfolio) is still sitting at a 40% profit – though it is down nearly 20% since the reporting date.

The fees are too damn high!

While this little anecdote formed part of a longer story (full story on page 13 and 14 of the letter) about ignoring doomsayers and spending time “in the market”, the part that stood out to me was the lesson about fees. The beauty of fees is that they’re the one aspect of investing that investors have total control over – you can’t guarantee higher returns, but you can lower your fees, and the end result is the same.

“On March 11th, it will be 77 years since I first invested in an American business. The year was 1942, I was 11, and I went all in, investing $114.75 ($1,772.02 in today’s dollars) I had begun accumulating at age six. What I bought was three shares of Cities Service preferred stock…

…If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter). That is a gain of 5,288 for 1. Meanwhile, a $1 million investment by a tax-free institution of that time – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion.

Let me add one additional calculation that I believe will shock you: If that hypothetical institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various “helpers,” such as investment managers and consultants, its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion. That’s what happens over 77 years when the 11.8% annual return actually achieved by the S&P 500 is recalculated at a 10.8% rate.”

To many more letters ahead

While Charlie’s age is beginning to become hard to ignore (though his wit is as sharp as ever), it’s encouraging to seeing Warren’s apparently great health for his age. Though Ajit Jain and Greg Abel are sure to be excellent stewards of investor capital in their absence, I certainly hope it will be many more years before we are reading an annual letter penned by anyone other than Buffett himself.

Read the full, 14-page letter here.

2 topics