Investors blindsided by global conflict risks

In the AFR I write that back in October 2021, we warned that the risk of global military conflicts was much higher than many people---including those in markets---assumed, and that the outbreak of war could have deleterious consequences for asset prices.

We further recommended that investors embrace a “democratic” ESG criterion and stop allocating capital to dictatorships and despots, specifically calling out the NSW government for providing debt and equity funding to Russia ($75 million), Saudi Arabia ($45 million), China ($225 million), and the UAE ($15 million).

It’s funny how events change perspectives: I suspect some folks initially thought we were being alarmist. Yet our warnings were based on advanced academic research that applied sophisticated statistical and machine learning methods to 160 years of military, economic, demographic, social and political data to estimate---for the first time---the objective empirical probabilities of conflicts erupting between different nation states.

The truth is we have been highlighting these risks for over a decade. In 2012 this column asserted that “the most profound hazard Australians face is the risk of war”. “We invest vast taxpayer resources – more than $30 billion each year – nominally insuring against it. Yet despite more than 200 conflicts since 1900, causing 35 million deaths, there is a startling dearth of quantitative research on forecasting the frequency and severity of wars. Here I am talking about projecting the “probability distribution" of future conflicts…”

After years of work, we were finally able to address this conflict modelling lacuna. While the data-set used in the models ends in 2020 (i.e. they do not have the benefit of information after 2020), they nonetheless put the probability of a full kinetic conflict between Russia and the Ukraine at a substantial 1-in-4 to 1-in-5 (or 22.2 per cent) over the next 10 years. Crucially, this specific probability included a declaration of war between these countries. Worryingly, the conflict probabilities between the US and China, and China and Taiwan, were an even higher 45 per cent and 74 per cent, respectively.

Sadly, the Russian/Ukraine risks have come to fruition in 2022, wreaking havoc on markets. And it has suddenly dawned on investors (like NSW) that lending money to dictatorships, such as Russia, is a terrible idea. Indeed, there has been an international rush to dump all Russian exposures, which had been widely held as part of many investors’ emerging market equities/debt portfolios. Years ago, I discovered that even my own mother had been put into Russian and Chinese equity funds, which I immediately convinced her to exit.

In October 2021, this column explained that “we require all investments to be domiciled in democratic, rather than authoritarian, states where there are minimum safeguards regarding the rule of law, property rights, freedom of individual and religious expression, human rights and so on”. “Without this democratic criterion, it is easy to end up lending money to the likes of Vladimir Putin and the Saudi royal family.”

Nobody seemed to care back then, but do they now. To be clear, our democratic maxim is not just about ethics. It is founded on the idea that transparent democracies give investors a much better chance of having their legal rights enforced and protected. Countries like Russia and China are uninvestable because no serious investor can have confidence in the rule of law, property rights, enforceability of claims, and/or the integrity of the financial, risk and other information disclosures that emanate from companies that are subject to the dictates of totalitarian regimes.

Russia has just banned foreign sales of domestic investments. China imposed similar constraints during their 2015 equity market crash. Ask Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, how he feels about becoming the president’s personal play-thing!

These geo-political risks only amplify the negativity we have communicated regarding almost all asset-classes since late 2021 given our view that inflation pressures would force the Fed to unwind its stimulus and hike 6-7 times this year. In December, we argued that equities would suffer a significant correction, taking other risky asset-classes, such as crypto, with it. We were also very negative on our own asset-class, fixed-income, forecasting that credit spreads would widen sharply, and that interest rate duration would suffer large losses.

The US equities market has since declined by more than 10 per cent through to its recent nadir on 23 February. Bitcoin slumped from US$52,000 to US$33,000 over the same period. And global credit spreads have sky-rocketed while interest rate duration has been hammered. In respect of the latter, the AusBond Composte Bond Index, which is the main Aussie fixed-income benchmark, fell by 3 per cent between 31 December and 23 February this year.

We are now in a new twilight zone where markets have come to grips with pricing in an aggressive Fed, handicapping six hikes this year (compared to only three in December), and rerating risk premiums much higher such that asset prices do look somewhat more attractive.

One interesting observation from the day-to-day price action is that the equities (and crypto) guys are all still glass half-full. Every equity investor I know thinks a lot of bad news is in the price: six hikes is the real deal, after all. They also seem to believe that if equities tank by more than 20 per cent, the Fed will bail them out. And Bitcoin looks much cheaper than it did in December. Indeed, digital currencies received a boost a soon as the sanctions on Russian banks came into play and the kleptocrats in Moscow started shifting cash off the grid into that preferred money-laundering instrument: crypto.

This short-term positive could quickly become a long-term negative if the West decides it needs to regulate crypto out of existence to crush the criminals who rely on it for anonymity.

The glass-half-full dynamic is evidenced in a strong buy-the-dip reflex, especially in US trading hours. It has been stunning to watch US equities slump by 2-3 per cent in the Eurozone session, only to rally back into the black in US hours.

There are, however, silver linings for Australia, which truly remains the “wonder down under”. As a net energy exporter, we are getting the benefit of huge increases in the value of our most important commodities: iron ore has surged from US$87/ton in November 2021 to over US$150/ton; our thermal coal prices have jumped from US$150/ton in January to US$370/ton; and LNG prices have doubled from a year ago.

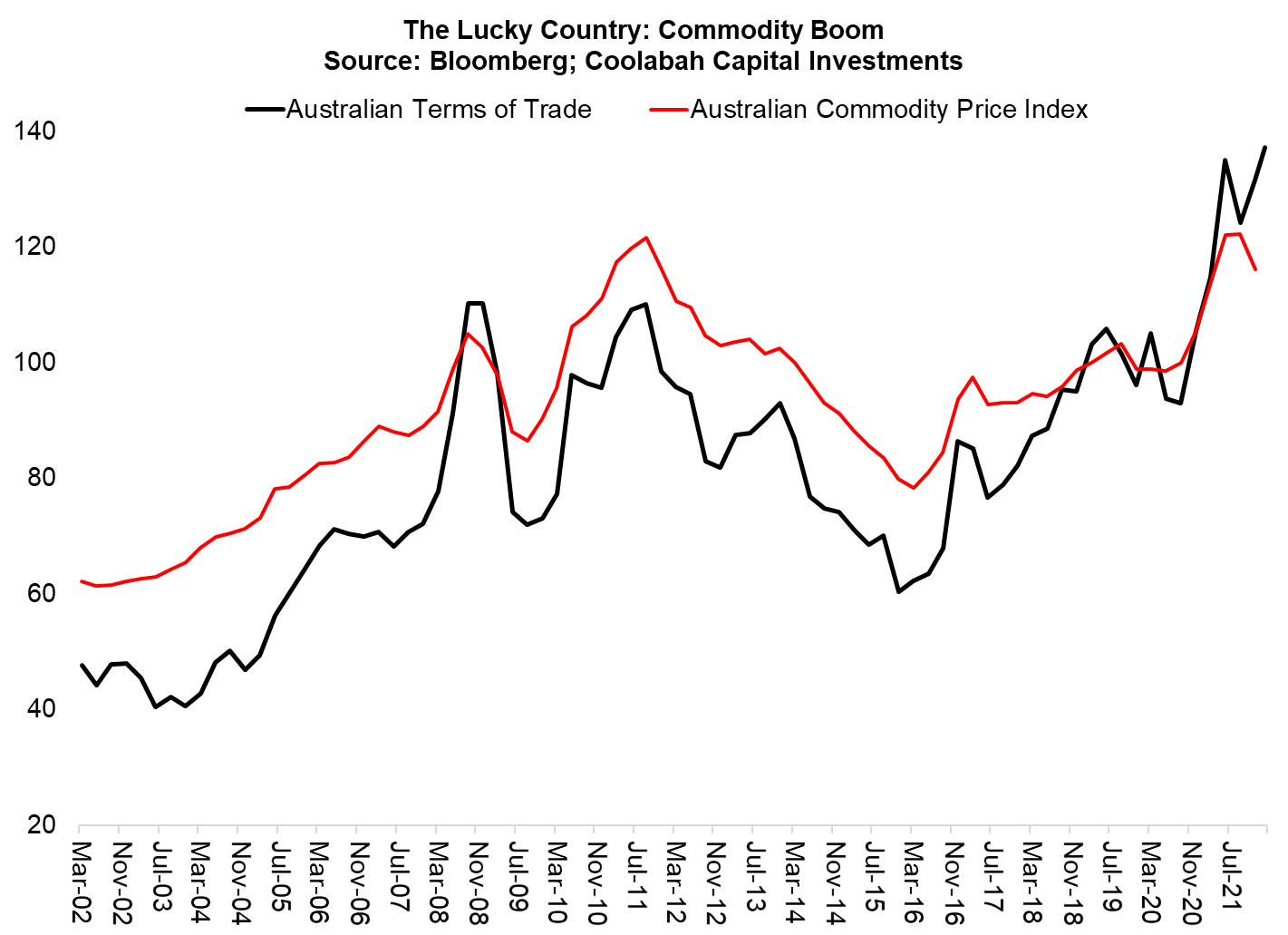

In fact, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s official index of commodity prices in trade-weighted terms has, as Terry McCrann recently pointed out, appreciated by an incredible 46 per cent since December 2019. It is now on par with the peak registered in the great commodity price boom a decade ago. This has meant that Australia’s terms of trade, representing the ratio of our export prices to import prices, is likewise at similar levels to its maximum point in the last cycle.

The commodity boom is providing an unexpected revenue boost for both State and Federal budgets with Western Australia, Queensland, and New South Wales, in particular, making out like bandits. On our seasonal adjustment, WA’s general government surplus increased from $1.7 billion in the third quarter to $2.3 billion in the fourth quarter of 2021. This means WA has achieved a $4 billion surplus in the first half of the financial year compared to the state’s forecasts of a $2.8 billion surplus for 2021-22 as a whole. And there are more revenue upgrades to come.

Another silver lining is evidence of global investor diversification out of Europe and into relative safe havens like Australia and the US. In recent months, the Japanese have poured billions into State government bonds, which pay the highest yen-hedged yields of any AAA or AA rated government bonds globally.

The next big event risk is where the Fed’s cash rate ends up. Investors currently believe the Fed’s terminal cash rate will be only 1.75 per cent. Our analysis implies it will move to 2.50 per cent as a minimum, which could precipitate another materially adverse repricing of risk assets. But that may be a story for late 2022 or early 2023.

3 topics