Is the 60/40 portfolio dead, or just on holiday?

I find it ironic that in any equity bear market we never hear the question “Are equities dead?” nor in the (albeit rare) bond bear markets do we hear the question “are bonds dead?” Yet, I’d love a dollar for every time I’m asked the question is the “60/40 portfolio dead, or just on holiday?”

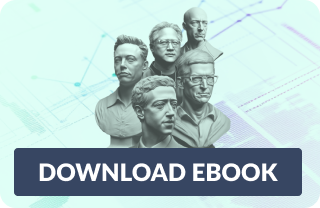

Since its genesis in the 1950s as a key tenet of Harry Markowitz’s Modern Portfolio Theory, the performance of the 60/40 model has ebbed and flowed as market conditions have changed. Investors who have stuck with this model over the long run have been well rewarded. Those that have expected great returns, year in, year out have probably been frustrated, if not disappointed.

Please note that all charts are for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation to buy, sell or hold. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance and may not repeat.

Figure

1: US 60/40 Portfolio since 1900 (rolling 5-year returns)

There are a couple of key ideas that underpin the 60/40 approach:

- Over time, equity investors tend to earn a higher return than bonds, as compensation for the higher risk of owning equities. In other words, the efficient frontier is upward-sloping, with investors being rewarded for taking more risk. In this case, risk is defined as the volatility of returns.

- The correlation between bonds and equities is negative (especially in periods of equity market weakness). This means that returns from bonds could help mitigate drawdowns that episodically occur in equity markets and smooth returns to the investor through the cycle.

However, I think there are some shortcomings in these assumptions that are relevant to the topic of this article.

Firstly, the assumption that equity investors will earn a premium to bonds often only really holds over the very long term. Statistically, this means investors need to hold equities for decades – not just a few years – to be confident that they will be rewarded for the additional risk.

Using the 120 years or so of data underpinning the 60/40 portfolio above, to be 90% confident of achieving a return of 3.5% above US inflation, an investor would need an investment horizon of 23 years. To be 90% confident of achieving a return of 5% above inflation, the investors time horizon would need to be 58 years.

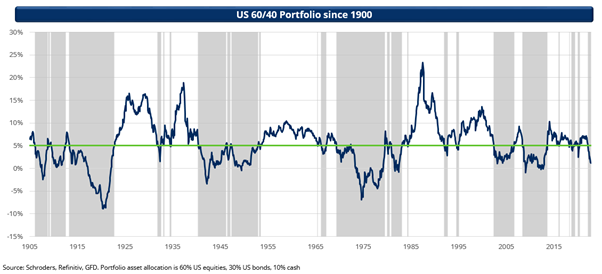

If you don’t believe me (perhaps because your reference period is the post-GFC world), it’s worth observing the chart below, which looks at both the nominal and real returns from US equities over the same period. It shows that equities have been in secular bear markets over 40% of the time, with the most recent spanning the decade of the 2000s from the bursting of the tech bubble to the wash out of the GFC. This means timeframes matter, both in terms of timing (as starting to invest in a 60/40 portfolio in 2000 would result in very different 10-year outcomes than someone who invested a decade later), and in how long you need to be invested to ensure the 60/40 portfolio delivered on expectations.

Figure 2: The US Sharemarket since 1900 (secular bear markets shaded)

Secondly, bond and equity returns are influenced by a whole range of factors through time and rarely achieve the theoretical equilibrium implied by the Markowitz model. Asset valuations can and do significantly deviate from “fair value” and this can have a material impact on future returns and the risk around those returns as valuation pressures are realised.

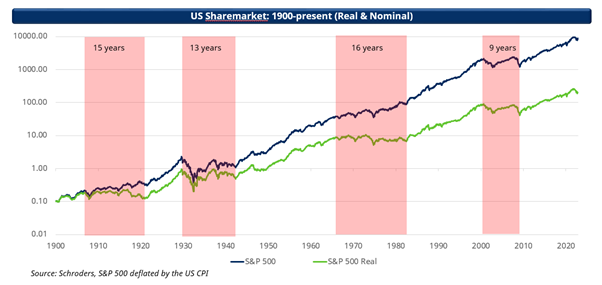

Thirdly, correlations between bonds and equities vary significantly over time. And depending on the underlying drivers of markets (that is, the nature of any shock driving market volatility) it could be both positive and negative, exaggerating volatility or dampening it.

Figure 3: Bond / Equity Correlations through time

This is all-important in thinking through the question of whether “the 60/40 portfolio is dead or on holiday”. The simple reality is that market conditions in recent years (predominantly the dominance of Central banks and liquidity) had driven both bond and equity valuations to extremes. This was great for investors in both bonds and equities, as yields collapsed in the former and because of the growth and liquidity in the latter.

And as a result, for investors in a 60/40 portfolio, it made the future for this approach challenging to say the least, as it compressed risk premium and future returns. We’ve been concerned about future returns for some time and this concern was realised in 2022.

With the return of inflation upending the liquidity trade, as Central Banks have aggressively raised rates (causing bond prices to collapse and yields to rise), equity markets have weakened. This has occurred as valuations realign to a higher interest rate environment and as the implications of tighter policy conditions flow through to future earnings expectations. The common factor of inflation has meant that bonds and equities have often moved in nearly the same direction (and quantum), meaning no significant diversification benefit. But this has all played out relatively quickly, and while it’s not over yet, the worst on the bond side at least is likely behind us.

Looking forward, I think we are in a much better position for a 60/40 portfolio to deliver. Equity valuations are now closer to equilibrium than they have been for some time. Higher bond yields also suggest that if the markets' focus in 2023 becomes recession, then while this could be problematic for equities, bonds could returns as an effective hedge (unlike 2022). With the right timeframe in mind, the 60/40 portfolio could do well from here.

The 60/40 portfolio was never perfect. But it has, and does, provide a robust anchor to build an investment framework around. That said, being aware of its flaws and limitations are just as important.

Take advantage of opportunities wherever they exist

With the flexibility to invest across a broad range of asset classes, we aim to help investors grow their wealth with a reduced risk of losing money when markets fall. Visit the Schroders website to learn more.

2 topics

1 fund mentioned