Is the Aussie residential market bottoming?

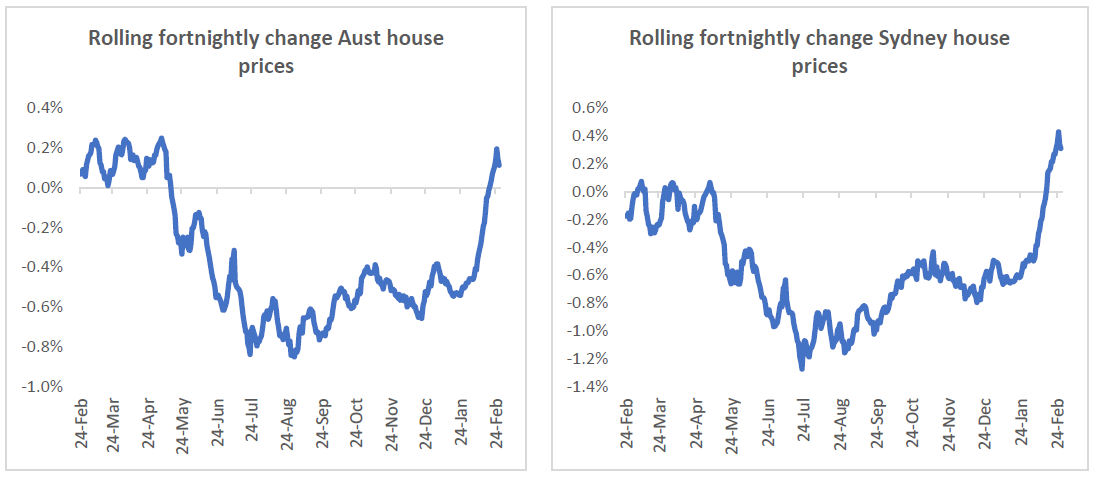

According to CoreLogic data, Sydney residential prices recently recorded their first increase in 13 months (+0.3%) while national residential prices were relatively flat (-0.1%).

This stall in national price declines has occurred in the face of a continued ramp-up in official interest rates (and associated mortgage rates) and has sparked yet another national debate on the future direction of the Australian residential market. Specifically, has the market bottomed?

Looking more closely at the daily data, the stabilisation of values over the month seems to mask a sharp recovery in the second half of February (based on change in fortnightly values) driven by the country’s largest market, Sydney (see charts below).

This ‘recovery’ comes at a curious time. Since January, still-elevated CPI readings and a resilient local economy have prompted the central bank to consider higher peak rates this cycle (at the time of writing, market expectations are for peak cash rate of 4.1% versus the current 3.35%). And the conventional wisdom is that Australian residential prices have a direct correlation with Australian mortgage rates.

Challenging the conventional wisdom

But is this right? Is the Australian residential market that simple?

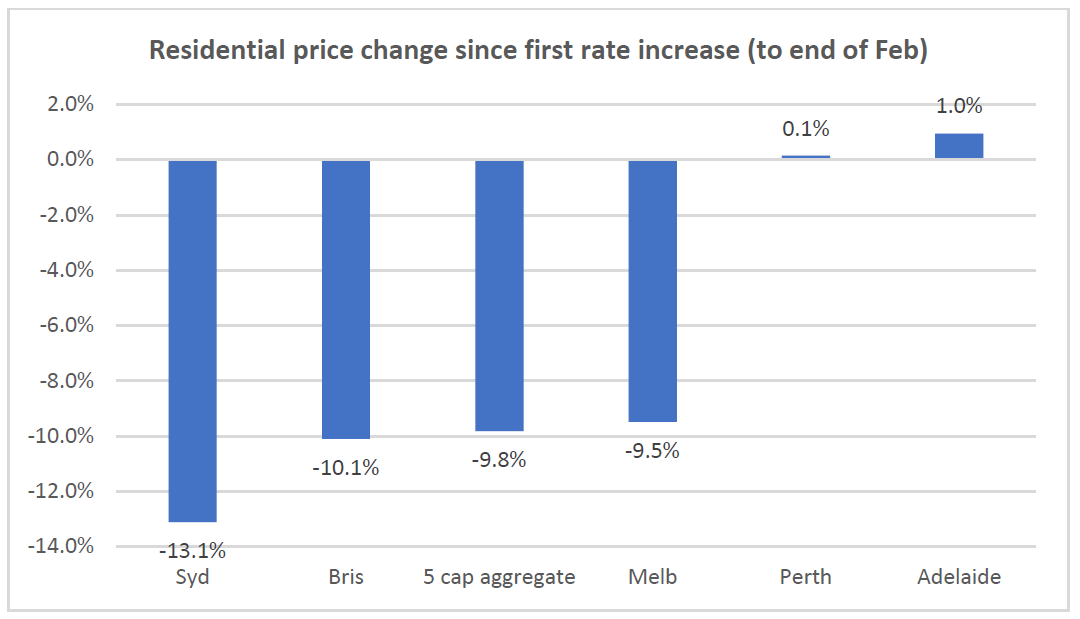

A cursory glance at the performance of each market across Australia since the central bank began to lift interest rates (4 May 2022) suggests maybe the market is driven by other factors rather than just the cost of funding. How can there be such a large disparity in city performances, when the official cash rate is applied to all?

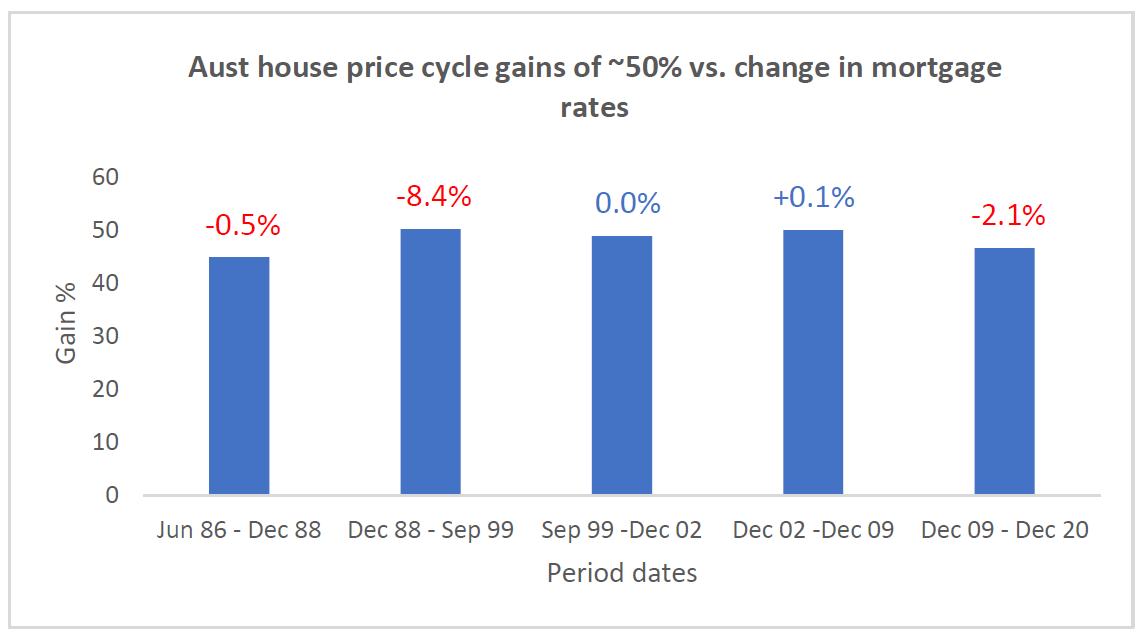

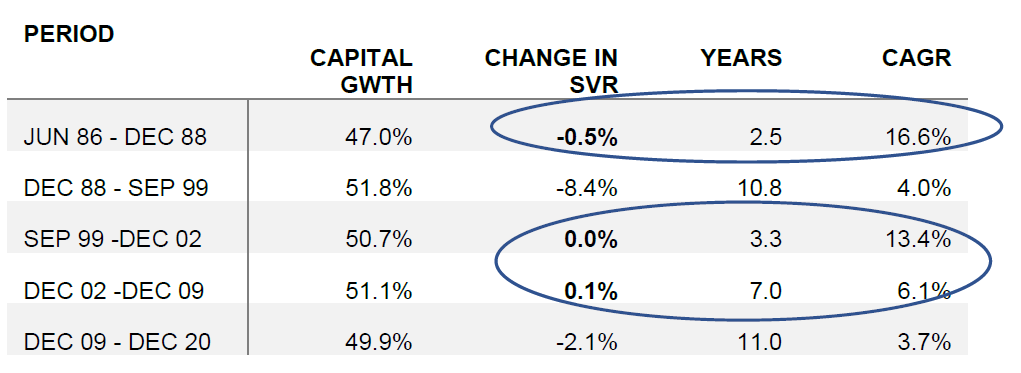

Despite the strongly held belief that higher (or lower) interest rates drive the returns of residential property, it is worth highlighting that in the past some of Australia’s best price gains occurred without any assistance from interest rates at all.

As the chart below highlights, looking at national housing data since 1986, and breaking the series into periods where incremental price gains of circa 50% were experienced, we can see some of these gains occurred when mortgage rates were flat or even increased (albeit slightly).

Moreover, the quickest 50% gains occurred when mortgage rates barely moved at all in the period Jun ’86 – Dec ’88 and again Sep ’99 – Dec ’02. Meanwhile, the slowest 50% gains occurred when mortgage rates dropped the fastest.

The table above suggests Australian property owners get the lowest annual capital gains when interest rates fall.

What lessons can be learned from the past?

The February data should not come as a surprise to seasoned real estate investors. There have been plenty of occasions where property prices have moved out of sync with interest rates in Australia. In the late 1980s, Sydney house prices increased significantly despite rising interest rates. The same occurred in Perth from 2002-2008.

Price movements that occur against the grain of interest rates appear to be driven by a mismatch between underlying demand and supply of housing stock. Sometimes this undersupply is incorrectly categorised as ‘property listed for sale’. However, a clearer picture of undersupply can be gleaned from the rental market, where there is shifting balance between underlying occupier demand and supply.

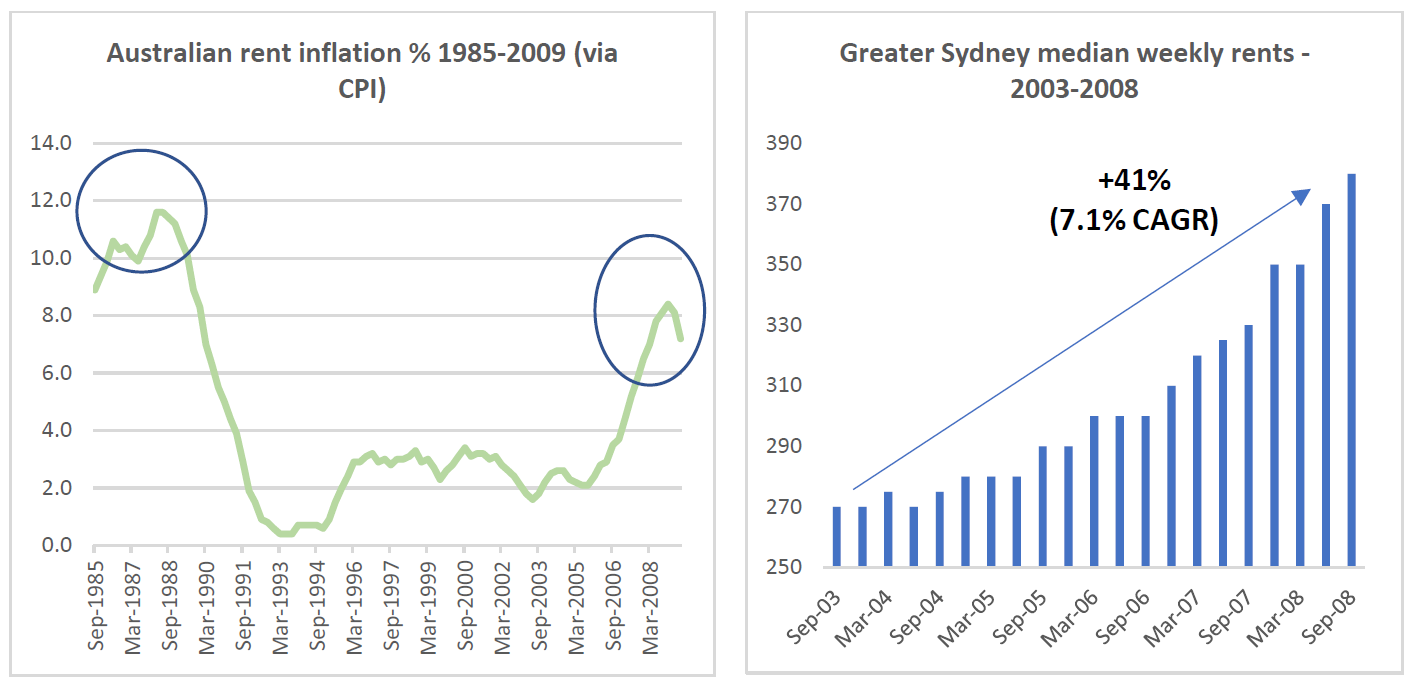

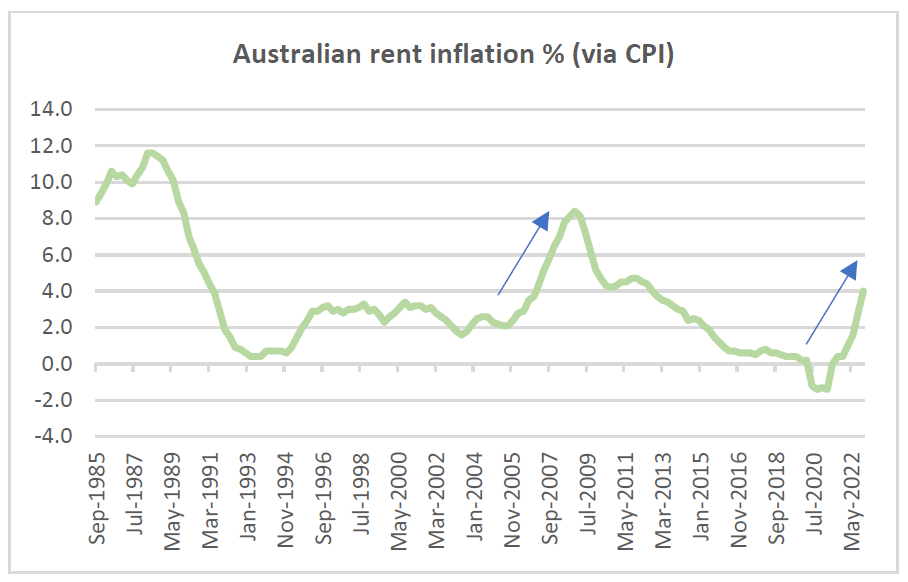

Looking back at the previous table, two of the periods where prices increased without the assistance of interest rates were ’86-88 and ’99-’09. The one common element during these two unassisted price spikes was accelerating rental growth.

It appears the imbalance between housing supply and occupier demand (as evidenced by the rental market) helped underpin the rise in house prices without any assistance from interest rates.

Of course, we are not in a stable interest rate environment today. Quite the opposite. However, the rental crisis today suggests we have another imbalance of housing stock, with rapidly increasing rents[1] working against the headwinds of rising mortgage rates.

Source: ABS, Quay Global Investors

What about the fixed rate mortgage cliff?

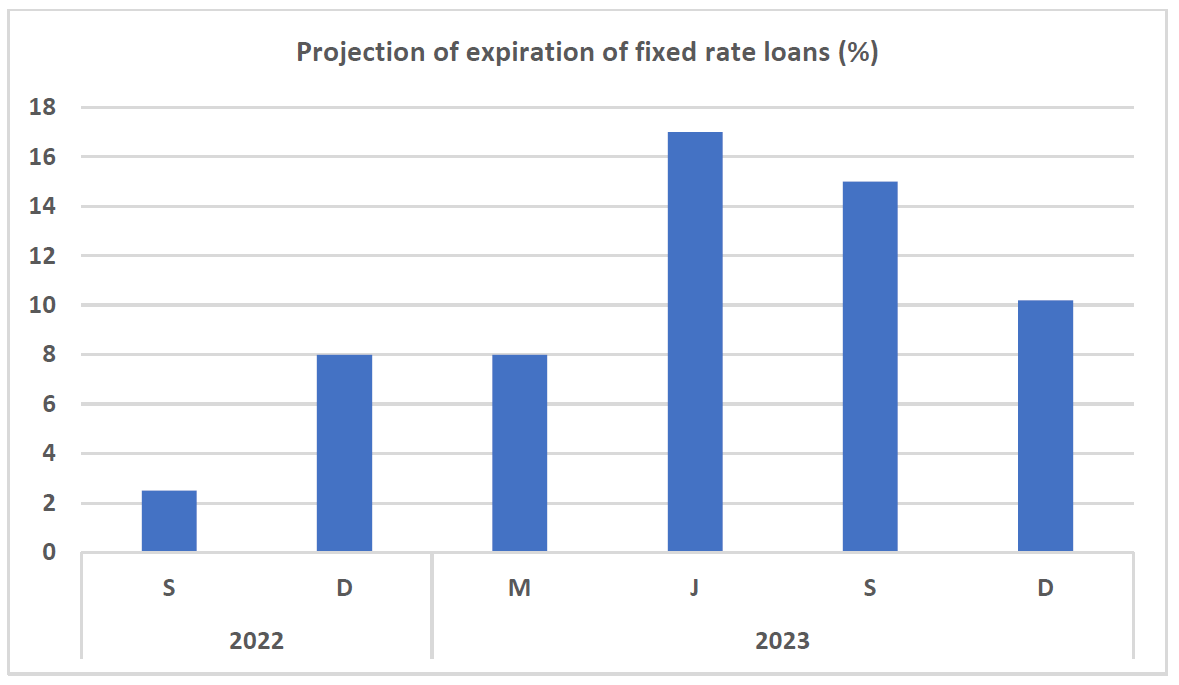

According to the RBA, around a third of outstanding housing credit is currently fixed, and roughly half of this is expected to roll off in the coming year.[2]

Given where fixed mortgage rates were in 2020-2021, these statistics appear worrisome. A meaningful percentage of Australian mortgage holders are facing a significant increase in loan repayments within the next 12 months. Is this a prelude for re-accelerating national house price falls? This scary observation is usually accompanied by the following chart (or a derivation of) presented by the RBA last year.

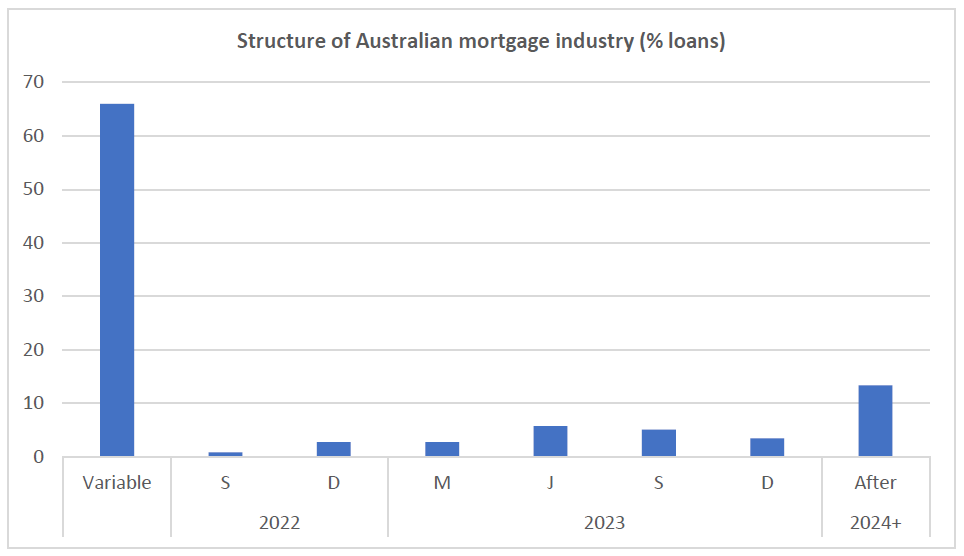

Thinking about this in a slightly different way, the RBA implies two thirds of outstanding housing credit is currently variable. Including the percentage of variable loans to the previous chart and adjusting the number of fixed loans as a percentage of total loans, we get the following ‘mortgage cliff’.

Equally accurate – just not as exciting.

Despite a 3.25% increase in the cash rate since May 2022 (with more expected), there are currently no signs of significant distressed selling; indeed, the number of homes currently on market remain well below pre-COVID levels.[3] If 67% of owners are not induced to sell despite higher rates, why would a further 16% of mortgages rolling off (half of the one third) have any significant impact?

Supply remains a concern

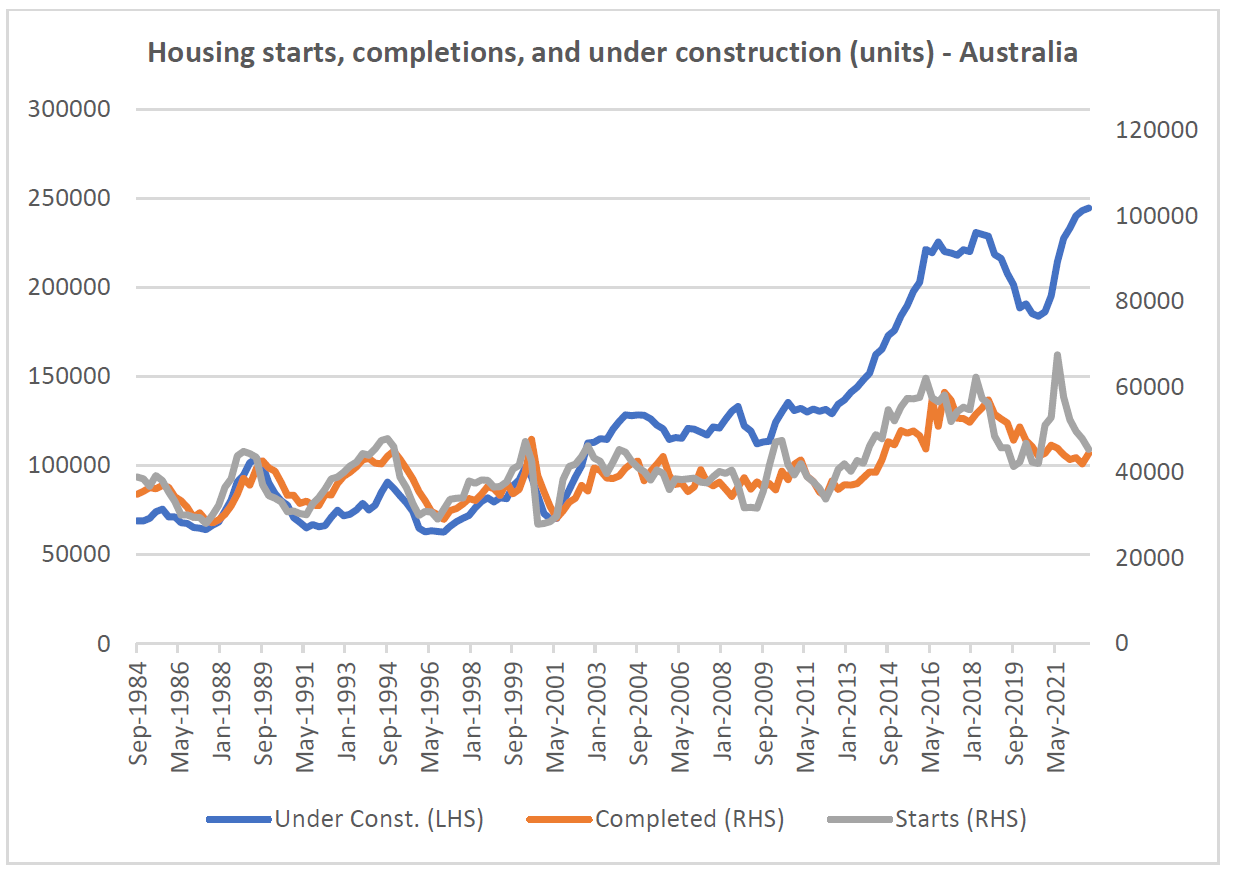

Rather than worrying about interest rates, there is still come concern about near-term new supply. As of September 2022 (the latest ABS data), across Australia around 250,000 dwellings are currently under construction and completions have yet to return to pre-COVID levels. However, new starts have collapsed as development feasibilities get squeezed. Normal run rate of units under construction is around 175-200k, suggesting excess supply of 50-75k can be expected over the next 12 months. This will ease some of the undersupply, although maybe not materially so.

Concluding thoughts

The resilience of the Australian property market in the month of February has caught a few people by surprise. However, it is always worth remembering that long-term dwelling or property prices bear very little resemblance to changes in interest rates. In the 10 years to 2009, house prices increased 225% without any change in mortgage rates (and that included the global financial crisis). However, it did coincide with a rapid increase in national rent, suggesting a stark demand and supply imbalance.

Recent data may suggest we have found a bottom in the national market, or it could be a false dawn. With two strongly opposing forces at play (interest rates and rent growth) and the uncertain timing of new supply, it’s a tough call. However, for long-term investors, it is worth remembering near-term movements in the official cash rates can be a distraction (and even a false signal), especially in times of clear demand and supply dwelling imbalance.

Investing in global listed real estate

Quay Global Investors, a Bennelong Funds Management boutique, focuses on the preservation and creation of wealth through innovative strategies in real estate securities. For more insights on global property, visit Quay’s website.

3 topics

2 funds mentioned