Is the end in sight for EBITDA?

Whether it is something you use or not, EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) has been a steadfast measure for earnings and valuation over the last 40 years. Despite a far wider acceptance of focusing on revenues, led by the technology sector (let’s leave that one for another day), EBITDA has morphed into a globally universal measure of business performance.

The pioneering of EBITDA

Like a great children’s folk story, no one truly knows who originated the concept but many point to cable television operator and Liberty Global Chairman John Malone (aka The Cable Cowboy) as the central driver behind taking EBITDA into the mainstream.

As William Thorndike, Jr. commented in his book “The Outsiders – Eight unconventional CEO’s and their Radically Rational blueprint for success”:

“Related to this central idea was Malone’s realization that maximising earnings per share (EPS), the holy grail for most public companies at that time, was inconsistent with the pursuit of scale in the nascent cable television industry. To Malone, higher net income meant higher taxes, and he believed that the best strategy for a cable company was to use all available tools to minimize reported earnings and taxes, and fund internal growth and acquisitions with pre-tax cash flow…

While this strategy now seems obvious and was eventually copied by Malone’s public peers, at the time, Wall Street did not know what to make of it. In lieu of EPS, Malone emphasized cash flow to lenders and investors, and in the process, invented a new vocabulary, one that today’s managers and investors take for granted. Terms and concepts such as EBITDA were first introduced into the business lexicon by Malone. EBITDA in particular was a radically new concept, going further up the income statement than anyone had gone before to arrive at a pure definition of the cash-generating ability of a business before interest payments, taxes and depreciation or amortization charges.”

Giving an inch, taking a lot more

Businesses have today taken this concept even further in the pursuit of providing their shareholders with a view of “cash-earnings”. A quick survey across ASX market presentations given in conjunction with the release of financial statements shows a multitude of items in the income statement are generally stripped out including:

- fair value losses (or gains);

- restructuring costs;

- share based payment charges;

- loss (or gains) on sale of assets; and

- essentially anything that can be deemed not operational or an ongoing part of performance for that business.

In reality, it is now very difficult to find a business that presents EBITDA as John Malone had intended it to be.

It certainly makes some sense to reconstruct or reconcile the statutory income statement to EBITDA or EBIT, and there are many good examples out there. Both of these measures do not actually appear in the purist form of financial reporting making up a Company’s financial statements (more on that later). In the case of EBITDA, the pursuit of disclosing cash-earnings and profitability free of fixed capital requirements can be very relevant for a business that wants to emphasise the cash generative nature of its operations. So too the same applies for EBIT, where a business wants to direct focus on earnings free of its chosen funding cost decisions. However, the question still stands, should EBITDA have ever been the basis for measuring earnings in the first place?

Differing industries have different fixed asset requirements either at the investment phase or maintenance phase of their asset lifecycle. This can mean differing depreciation and/or amortisation profiles (the ‘DA’ in EBITDA). Let’s assume an investor is reviewing potential investments in both a services business and manufacturing business with identical EBITDA. The obvious issue is that while their EBITDA might be the same, its very likely the manufacturing business has significantly greater fixed asset requirements – generally a very large plant outlay at the beginning of the asset’s life – versus a service business which might be able to get away with some laptops and a few desks to get started. The ‘DA’ is going to be fundamentally different.

Further adding to the disparities in reporting EBITDA is that the cost of debt funding, i.e. the interest paid (the ‘I’ in EBITDA) is unequal for all. Interest costs vary greatly for businesses in differing industries, where the type of asset, the security available and the certainty over future revenues impact the risk pricing decision made by a lender.

It makes it all the more understandable why Warren Buffett took a far more extreme view on EBITDA back in 2003:

“It amazes me how widespread the use of EBITDA has become. People try to dress up financial statements with it. We won’t buy into companies where someone’s talking about EBITDA. If you look at all companies and split them into companies that use EBITDA as a metric and those that don’t, I suspect you’ll find a lot more fraud in the former group. Look at companies like Wal-Mart, GE and Microsoft — they’ll never use EBITDA in their annual report. People who use EBITDA are either trying to con you or they’re conning themselves. Telecoms, for example, spend every dime that’s coming in. Interest and taxes are real costs."

So how did we end up here?

It is probably easiest to try and point the finger at accounting standard setters who have, over the last 15 years, issued new and amended accounting standards which require recognition of more income statement items previously preserved in balance sheets.

Businesses then argued it was necessary to provide “adjusted” results to separate the wood from the trees. However, if we are being honest, businesses have taken many liberties with the arguably flimsy definitional construct of EBITDA.

It is worth remembering that EBITDA is not a statutory measure that the ASX or ASIC can determine as right or wrong. So much so that in March 2013, ASIC issued its Regulatory Guide 247 (updated again in 2019) to try and regulate the meteoric growth in new earnings measures and attempt to have them at least reconciled back to statutory measures of performance.

It appears to have anecdotally helped in streamlining presentations, but it has also given preparers of financial information even more freedom to pick and choose earnings methods so long as a rather complicated table is included to bring it back to the statutory financial statements.

Welcome to the world of AASB16

In 2019, we were introduced to one of the more fundamental accounting standard changes in the last 20 years, AASB16 Leases (IFRS16 Leases under international standards). Seen as a polarising accounting standard, with users either loving it or hating it, the basic premise of the standard is the recognition of all lease arrangements on balance sheet (with some exceptions of course) including right of use assets (a new form of intangible asset) and lease liabilities.

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) estimated at the time that there were approximately US $3.3 trillion lease commitments in existence, of which 85% were operating leases and would now be recognised. These new assets then require the corresponding recognition of a right of use asset, and associated charge in the income statement categorised as depreciation, while the new liabilities are unwound as the lessee makes rental payments.

In practical terms, what we all knew as “rent” has now become “depreciation”. Behind cost of sales and employee related costs, rent (whether for property or other assets) is generally considered in the next layer of largest individual cost items borne by business operations. The calculation of EBITDA in its original intended form is even more blurred as it now excludes further operational costs of the business.

Businesses have responded across the last two years of reporting by now including EBITDA pre-AASB16 (what we used to understand as EBITDA) and EBITDA post-AASB16 (a higher EBITDA matched by increased depreciation charges) making it even more complicated.

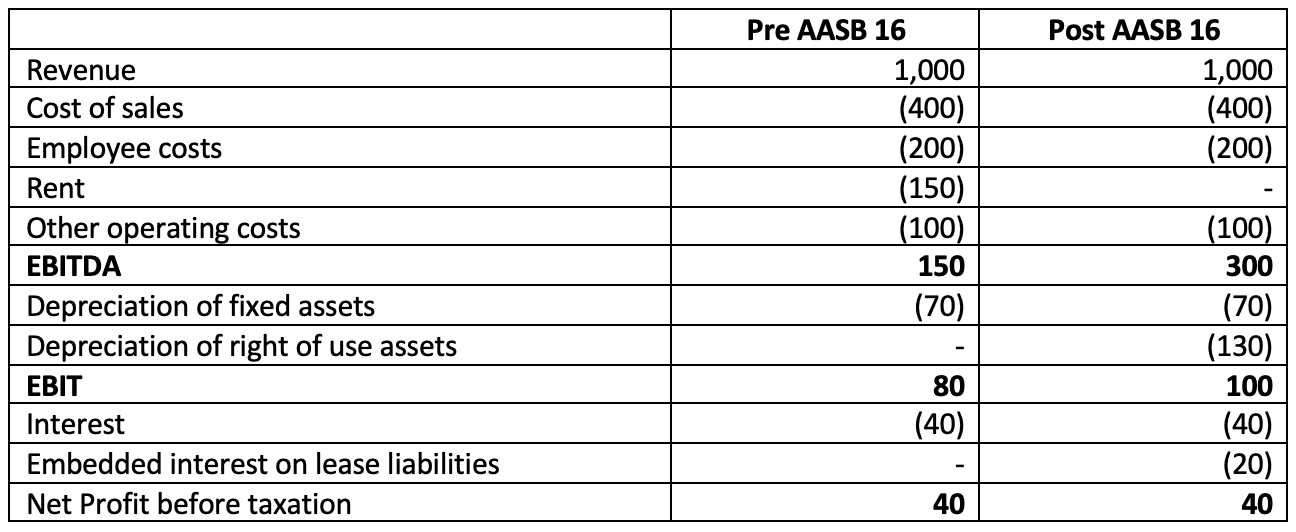

Set out below is a table showing the two presentation alternatives for a hypothetical company:

While the above is just a hypothetical model, and ultimately the Net Profit before taxation is consistent between the two (though in practice this is unlikely to be the case because of the reducing embedded interest charge over the profile of the operating lease period), the presentation of EBITDA (and EBIT to a lesser extent) are categorically different.

The implications of these continued changes pose two ongoing challenges for investors and businesses:

1. Is EBITDA still an appropriate measure as a proxy for cash earnings?

One could argue that EBITDA almost excludes as many costs as it includes. Strictly applying the definition of EBITDA would not provide a reader with a proxy for cash earnings.

2. How should businesses and investors apply multiples to determine business valuations in relation to M&A or general valuation principles?

Firstly, in relation to M&A, should company Boards and shareholders be prepared to agree to M&A valued on multiples of EBITDA? That is likely to trigger overpayments for assets. Secondly, the application of EV/EBITDA multiples as a basis for valuation estimates and peer comparisons need to be re-considered.

How can we adapt?

At this juncture, there is a strong case for businesses to shift away from EBITDA towards EBIT as their global measure of performance.

This provides a better value capture of fixed capital expenditure of the business, which is inevitably a key driver in free cash-flow. In addition, it also embeds in all lease arrangements now captured in different components of the income statement and cash flow statement. Ideally EPS finds its rightful place back as the focal point in market presentations, but one suspects that is a bridge too far.

In a potentially ironic twist, it is possible the accounting standards setters inadvertently reset the focus on earnings measures to EBIT through their most recent standard changes. This could be the most fundamental change to valuation metrics we have seen in the past 40 years since John Malone pioneered EBITDA.

If this does occur, we are still likely to see businesses continue to present “adjusted” results but the benefits of providing earnings measures that cover a more comprehensive view of the costs of operating and funding a business are obvious. This only helps to provide greater transparency to investors.

There is certainly a logical argument to say we are at the beginning of the end for EBITDA.

4 topics