Is the RBA Really That Bad?

Key Points:

• The RBA has been the subject of much criticism in the domestic press and around the BBQ since it began its rate hiking cycle

• Apart from a few faux pas, the RBA hasn’t really been that out of step with their global counterparts. They have risen rates by around the same amount, around the same time and have been left with around the same inflation problem

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has copped a good deal of criticism in recent months. The abandonment of yield curve control in 2021, following sustained market pressure, was a clear policy failure. Those who extended themselves financially to buy homes in 2021, comforted by the Bank’s language that the cash rate was unlikely to rise before 2024 at the earliest, may be regretting that decision. The RBA has been accused of doing both too little and too much to address still high inflation. They have also been accused of ignoring the financial stability risks around juicing house prices with ever lower interest rates. Most recently, the Bank’s awkward rate hike pause in April, which ended abruptly in May, caught markets and commentators off guard and made it seem like they really don’t know what they are doing.

In an attempt to redress some of these perceived failings, the RBA’s Governance framework has been re-written, with the existing Board losing its rate setting remit. Phil Lowe may also be the first Governor to not be offered a second seven-year term when his current reign ends in September.

In this month’s Market Insight, we review how much of the criticism is justified by looking at the RBA’s performance relative to its global peers. We focus on outcomes, more than communication, because we also speak and write about the outlook for the economy and markets and people in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.

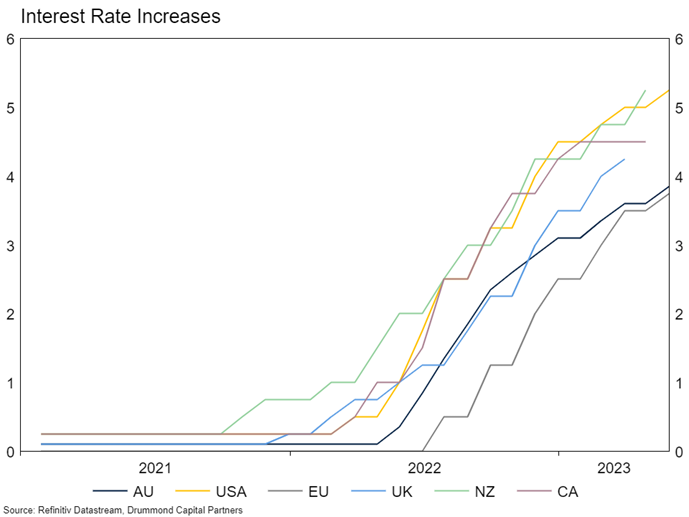

To begin, we should look at what the RBA has actually done versus its peers. At the most superficial level the RBA has generally lagged other central banks in terms of rate hikes. They started to move later than most and haven’t hiked as far, with only the Europeans lagging further behind. So, depending on whether you prefer a struggling housing market or higher inflation, it could be a tick in the win or fail box.

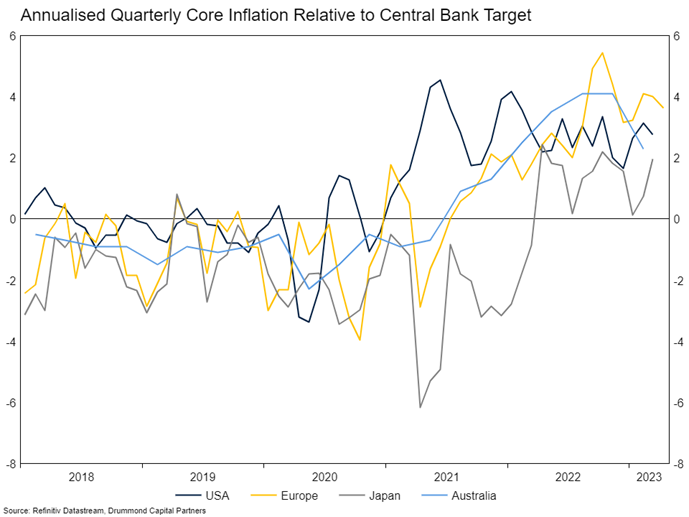

So where does a lagging central bank leave the Australian economy in terms of relative inflation? The simple answer is, pretty much as bad as every where else. The chart below shows current core inflation relative to target, with Australia sitting nicely in the middle of a bunch firmly above where they should be.

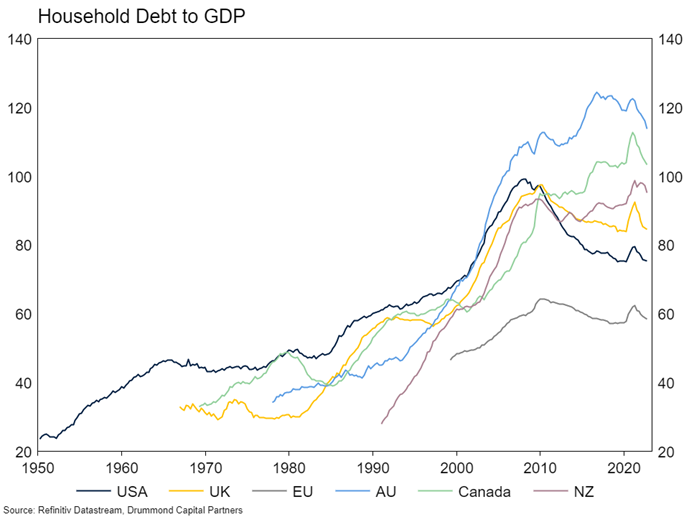

However, because of the structure of various consumer and business lending markets across these economies, different magnitudes of interest rate moves will have differing effects, at different times. Australia has higher household debt than most major economies, by a fair margin. Clearly, higher debt means interest rates will have more of an impact on households, all else equal.

Australia also has a relatively low proportion of fixed rate home loans, and the period in which they are fixed tends to be shorter than other economies. Thirty-year mortgages are common in the United States. Five-year mortgages are common in the UK and Canada. Work published by the RBA shows that because of this, it believes that rate hikes have a larger impact on aggregate household mortgage repayments than elsewhere .

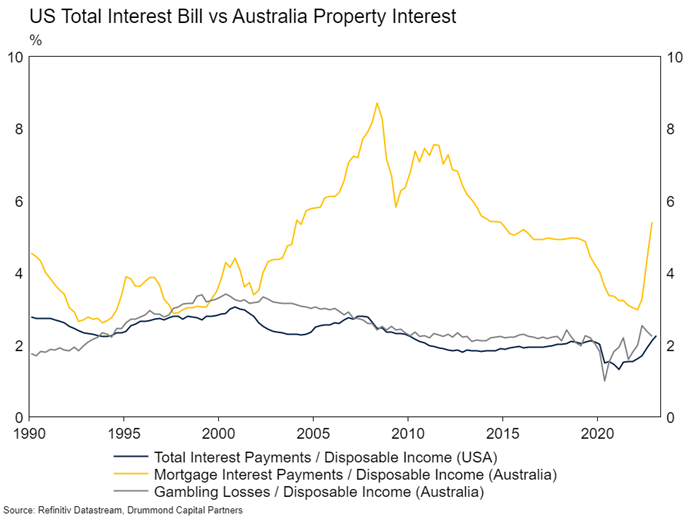

That is backed up by the Australian national accounts data (to Q4 2022), which shows the increase in mortgage payments as a share of disposable income in Australia has risen much more meaningfully relative to the United States since the hiking cycle began. However, relative to a baseline impost pre-Covid, the magnitude of increase has been broadly similar and as at Q4 2022, Australians still paid a much lower share of income to mortgage payments than they did in the late 2000s. Additionally, Australians pay a structurally higher share of their income on mortgage payments than Americans (who typically spend a similar proportion of their income on total interest payments as Australians do on gambling losses).

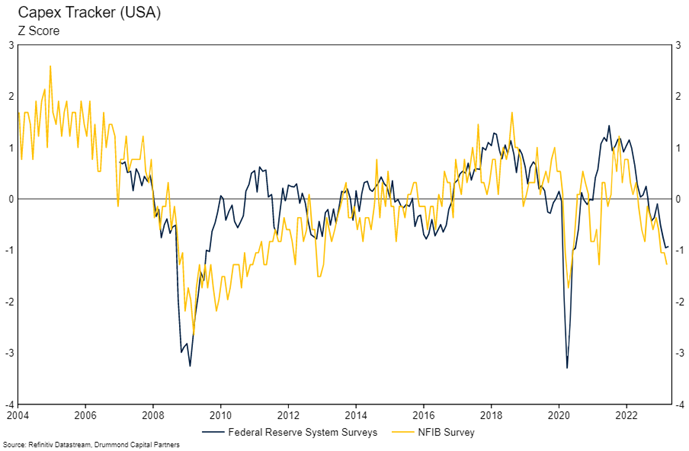

Of course, households are not the only people in an economy who borrow (and lend). Government and corporate debt are also important. Following profligate spending post the 2018 state election, the current high level of Victorian State Government debt combined with recent long term interest rate increases will likely force a path of fiscal consolidation (reduced spending) in that State in the years ahead. Corporate borrowers feel the impact of higher interest rates on profit margins and reduce capital expenditure (capex) as project evaluations no longer stack up. Reported capex intentions in the US have weakened considerably in the past year (see chart below). In aggregate, the Australian corporate and government sectors are less indebted than their global counterparts, at least in part offsetting the need for the RBA to be dovish due to high household debt.

The widespread consensus is that the key drivers of the original inflation spike (food and energy costs post the Ukraine invasion and supply chain driven goods inflation) have passed. Inflation is now being driven by services and housing costs.

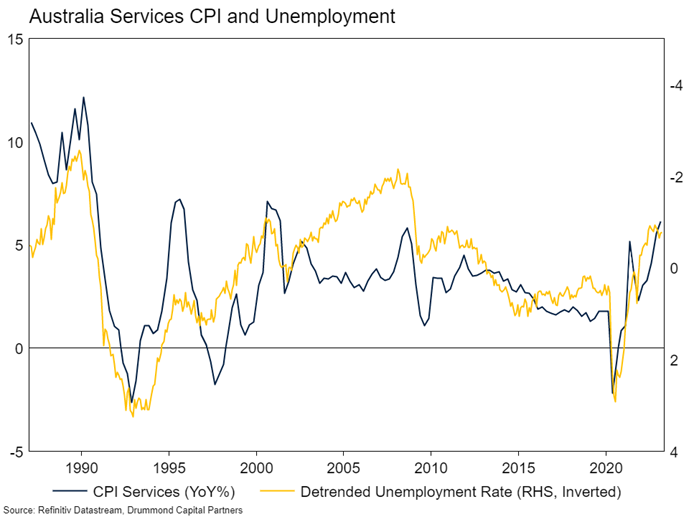

Services inflation is highly correlated with the unemployment rate (see below). Now, and in previous instances where services inflation has been higher than desired, the unemployment rate has been very low relative to its trend. Indeed, the unemployment rate in Australia is currently near a five-decade low. Additionally, there are no instances of services inflation falling meaningfully without an increase in the unemployment rate. If the RBA can deliver a fall in services inflation without a meaningful increase in unemployment, they deserve to be crowned the masters of the economic universe that many proclaim them to be. We think they will struggle to deliver that outcome, but also, probably shouldn’t be the only ones blamed for it either. Fiscal spending during Covid has a lot to do with where we find ourselves today.

The other key element of inflation in Australia (and elsewhere) is rental inflation. Again, this is closely related to the state of the labour market, but there are other drivers at play. The labour market relationship is pretty simple. If aggregate household earnings are rising quickly (which they tend to be when the unemployment rate is low and wages growth is solid), households have more capacity to pay rent for a largely fixed number of dwellings. Essentially, it is basic supply and demand. The housing stock is slow to respond to increased demand (given it takes a long time to plan, approve and then build a dwelling), so the price rises. As long as the labour market remains strong, we expect rental growth to remain high. Rental growth will also be supported by significant immigration and builder failures, which combined will increase demand for housing and reduce its supply.

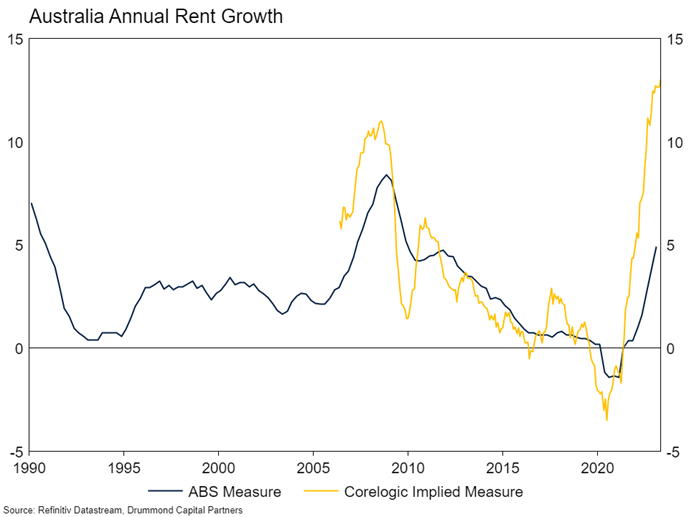

In addition, the rent price growth reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in the CPI numbers lags alternative measures (which capture new rental listing price growth rather than economy wide rental price growth) meaningfully (see below chart). This will likely keep rental price growth, as recorded in the CPI numbers, elevated for longer than otherwise may be the case as new annual leases “catch up” to the market.

Ultimately, whether the RBA (and other central banks) have done a good job will only be known after the fact. In the moment, the are operating under the same uncertain environment as everyone else. We have held the view for a long time that inflation will remain stickier than central banks hope until weakness in labour markets becomes apparent. This weakness will almost certainly accompany something that looks like a recession in our estimation.

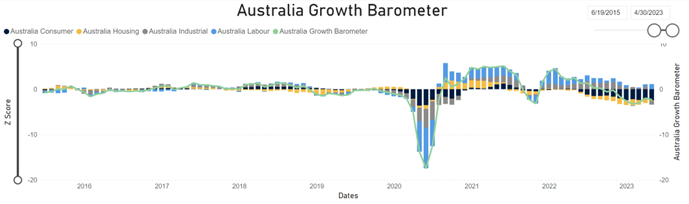

The rate hikes that have taken place to date in Australia have gone some way to slowing the economy. Our Growth Barometer for Australia suggests the last six months have been quite soggy, but not yet close to recessionary. This is consistent with the picture in other major economies, where growth has slowed, but it seems unlikely that a recession has begun. Whether this means more rate hikes are needed is one of the key questions for the second half of 2023.

Even if it turns out to be the case that there is a recession, we don’t think there is much use in blaming central banks – though many certainly will. Historic experience shows that recessions following policy tightening cycles are a feature, not a bug, of our economic system. Soft landings are exceptionally rare, particularly when inflation is this far away from target. Regardless, our portfolios remain conservatively positioned. We think we are closer to the end of this bear market than the beginning and have considerable dry powder in the portfolios to re-allocate to risk should a recession occur.

1 topic