Is uranium in a structural bull market?

The Structural Change in Uranium Pricing

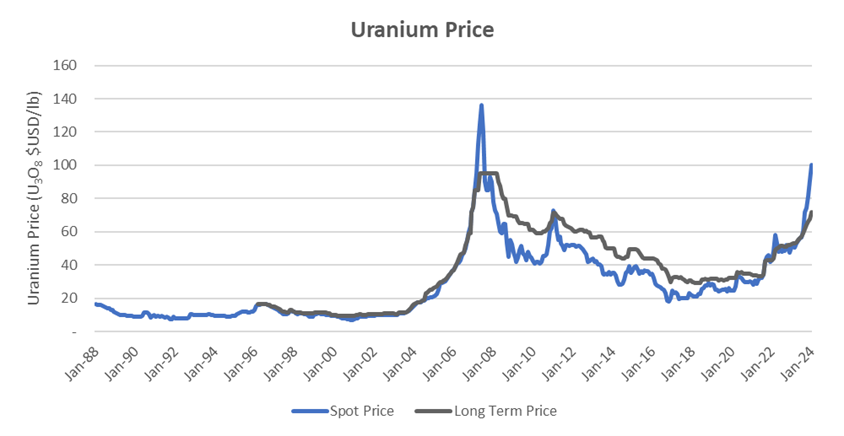

Uranium was the poster child of 2023, with a monster move of around +90% for spot prices through the dismal conditions for battery minerals. If you had some uranium in your portfolio, you could pay for counselling over lithium.

In this wire, we consider the backdrop to this move, and why higher prices will likely hold above $50 USD/lb. in order to incentivize new uranium production.

Developing Nations Dominate New Reactor Builds

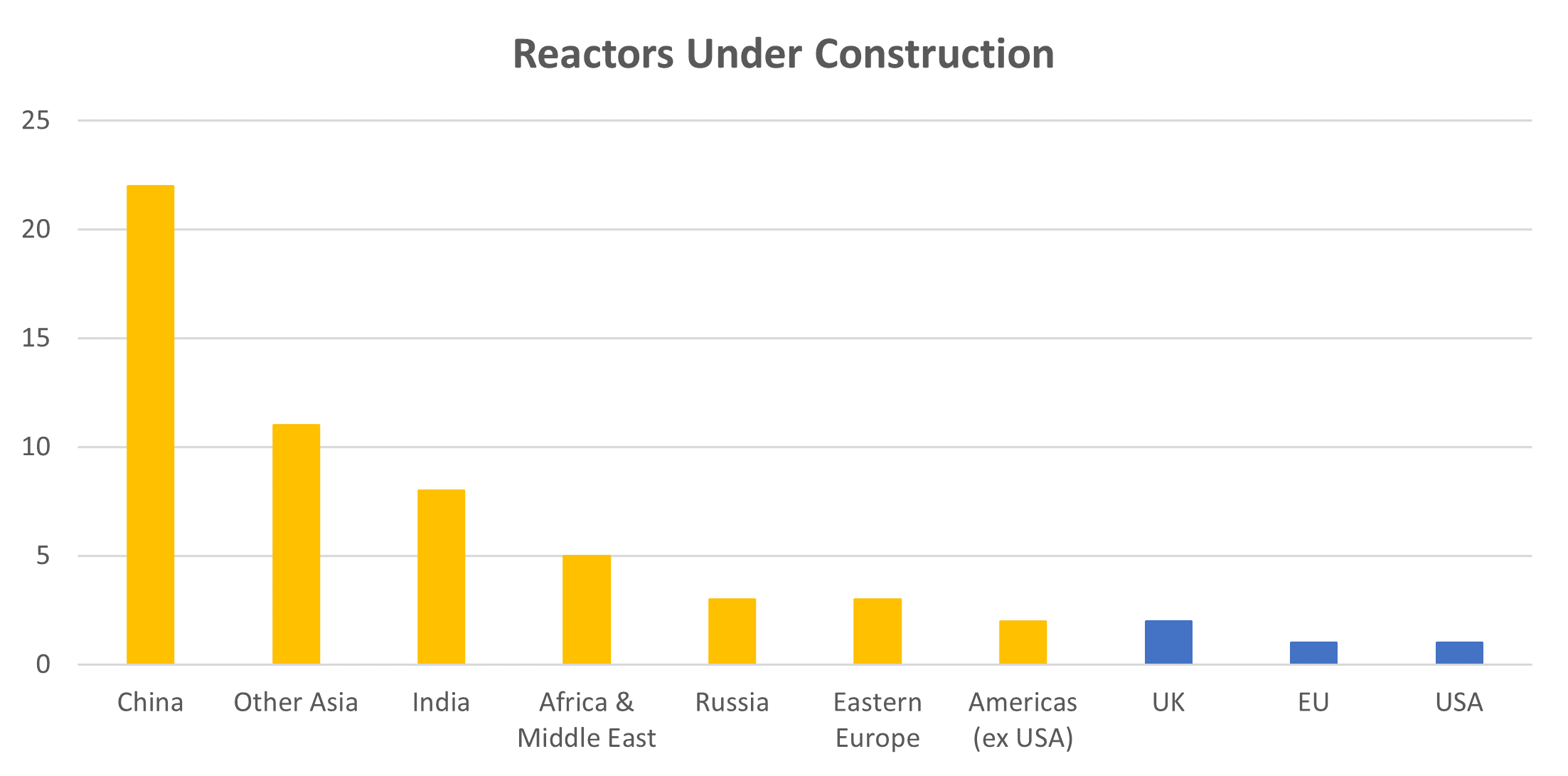

There are several reasons for this turnaround, but the primary driver is future growth in nuclear capacity in the developing world. The West has largely curtailed the development of any new nuclear plants and countries like Germany and Japan have either closed or shuttered existing rectors. On the other hand, China and India, plus other Asian nations, are forging ahead with new reactors. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), there are 437 operating reactors worldwide, with another 58 under construction.

These are largely in the developing world, Figure 2.

China has a huge program of nuclear reactor construction, while China and Russia now dominate new reactor design.

China is Vigorously Pursuing Nuclear Power

When China decides to do something, everything happens faster and on a much larger scale than any other place on Earth. This is true of solar and wind power, along with the blistering pace of growth in electric vehicles, and various battery technologies.

The same is now clear with nuclear energy, as a number of long-term Chinese R&D programs start to bear fruit with pre-commercial demonstrations, and commercial pilot plants, Figure 3.

Evidently, the Global Power Transition between the developed economies and developing economies is not limited to strategic competition in AI, and semiconductors. It also involves the design of nuclear reactors.

China was the first country to open a commercial Small Modular Nuclear Reactor (SMR), called a pebble-bed reactor. This fourth-generation reactor design uses a high-temperature helium gas coolant, operating with graphite coated fuel pellets.

The Shidao Bay plant is one of several initiatives within China to pioneer new reactor designs with the intention of shortening the time for construction, increasing safety, and reducing capital cost.

In addition to the pebble-bed fourth-generation design, China has invested in Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) experimental reactors based on a thorium fuel cycle. This is not the first time such ideas have been explored. They were popular in the 1960s with research efforts in the USA, at Oak Ridge, and in the long-running R&D program in India to develop a full thorium fuel cycle using Fast-Breeder Reactors (FBR).

The nature of strategic competition in technology is that populous nations with a large complement of scientists and engineers, the human capital, combined with prudent long-range planning of the R&D effort, are those who are likely to succeed.

India and China are both well qualified to succeed with nuclear reactor design.

The Chinese and Indians are not alone in pursuing novel designs for small modular nuclear reactors (SMR). There has been considerable press coverage in the West over plans by Rolls Royce, and others, to develop new designs of this type.

The Passing of The Peace Dividend

The other factor affecting the supply and demand balance for uranium is the draw-down of the peace dividend from nuclear arms reduction, see military warheads as a source of fuel.

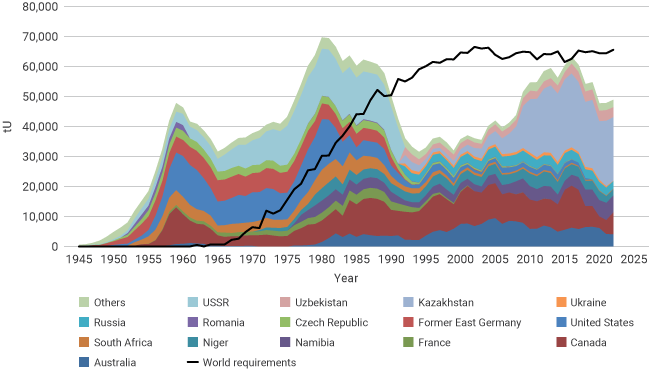

As reported by the World Nuclear Association, the early production of uranium was destined for military use in construction of the massive nuclear weapons arsenals of the Cold War. The growth of Atoms for Peace, as envisioned by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, did not really achieve much traction until the civilian nuclear reactor fleet grew in the 1960s.

The thing about uranium is that has several different isotopes. These are chemically identical but have different nuclear uses. Nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons share one trait in common. They both require special isotopes of uranium that are fissile. This means that the atomic nucleus can be split, to release energy by nuclear fission.

Most uranium in nature is the non-fissile U238. This is useless in a nuclear reactor, or nuclear weapon. What you need for both is fissionable U235, or the plutonium isotope Pu239. When you mine uranium in nature it is about 0.7% U235, and the rest is U238.

This is the same ratio, everywhere, since it arrived here as soot from an exploding star.

You only need 5% of the U235, in a reactor versus 90% or more in a bomb. This Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) is both expensive to produce, and very tightly controlled by the IAEA. This is why most facilities stop at Low Enriched Uranium (LEU). You cannot make a bomb with it. You can convert some of your U238 to Pu239 and maybe make a bomb or use that as fuel. This is called Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX) and represents an alternate dual-use path for development. There are designs called Fast Neutron Reactors (FNR), that make their own plutonium.

In the aftermath of the first Cold War, Russia and the USA entered into agreements to reduce their arsenals of long-range nuclear weapons. This led to two treaties, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties I and II, known as START I and START II. The dismantling of Cold War nuclear warheads, from the early 1990s onwards, liberated large quantities of HEU.

Kilogram for kilogram, one unit of nuclear warhead material can be blended down to almost twenty units of nuclear fuel material. This is done by mixing it with the plentiful U238.

For almost three decades, Western civilian nuclear reactors burned this peace dividend, which is now abating. This period shows up as the dip from the late 1980s through 2010 in Figure 4.

We have now chewed through most of the nuclear weapon material that was made available for use in civilian programs. Obviously, once you split the uranium atom, it is done.

There is no recycling of any of this material. Eventually, it will turn to lead. Wait a million.

When you add that up, with new reactor builds, and existing reactor refueling, the world has now reached that point where it needs, once again, to mine more uranium.

The Geopolitics of Uranium Supply

Uranium seems set to enter a long-term bull market that is driven by new reactor builds in developing nations combined with the end of the peace dividend drawdown of former military inventory.

While Western nations can likely cover their own reactor fuel requirements, we should recognize that supply chain security is subject to geopolitics.

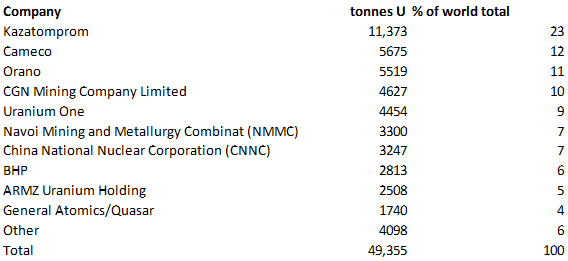

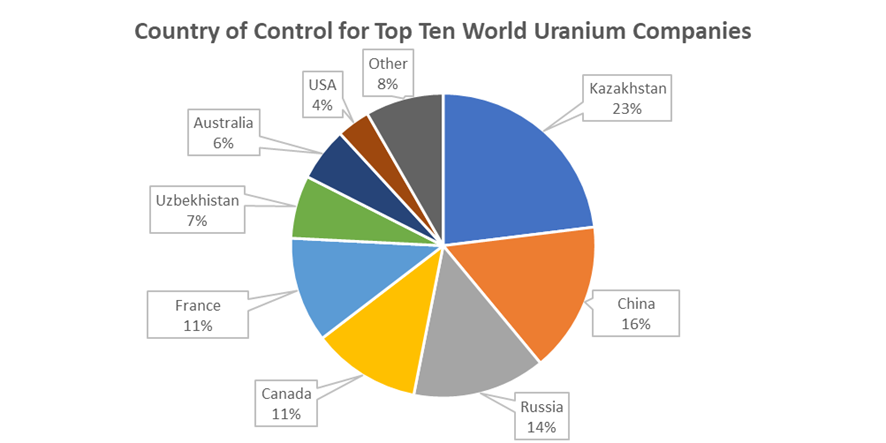

The supply of uranium is dominated by just ten companies, Figure 5.

This geopolitical factor is made stark when we examine the countries which control the ten largest uranium producers, Figure 6. China, Russia and mid-Eurasia dominate.

You can see the outlines of future nuclear materials trade in that one pie chart.

Opportunities in Australia

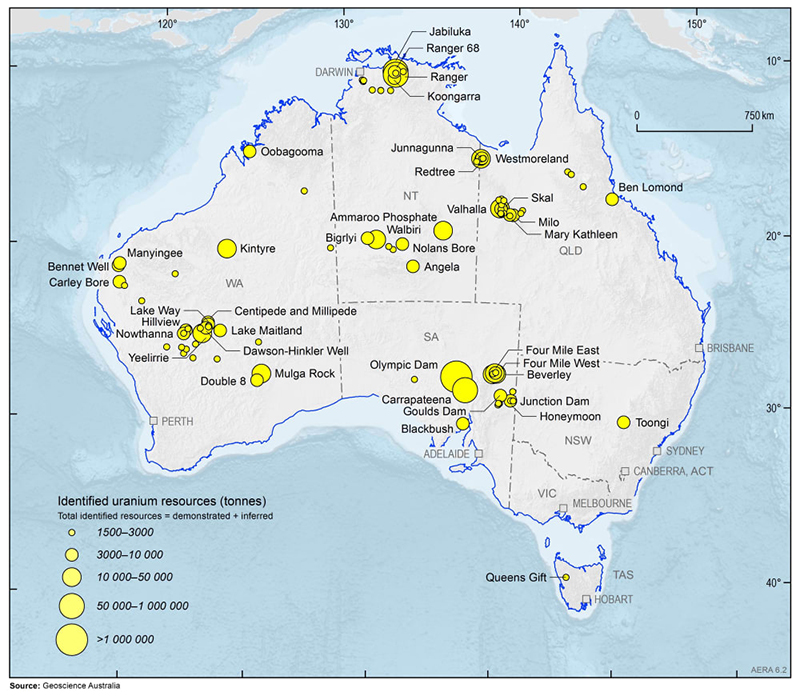

The largest ore deposits of uranium are to be found in Australia, Kazakhstan and Canada. The Australian share of global uranium resources is around 30%, but our global production share is only around 10%. This comes from two currently operating mines, Olympic Dam, owned and operated by BHP Group ASX: BHP, and the privately held Four Mile mine, owned by General Atomics subsidiary Quasar Resources, and operated by Heathgate, see Figure 7.

The largest known uranium resource globally is Olympic Dam. This is a large complex ore body of the Iron-Ore Copper Gold (IOCG) type, with rare earths and uranium. The flow sheet for Olympic Dam enables separation of the copper, gold, silver and uranium, but not rare earths This mine is the largest producing uranium mine in Australia, about 6% of the world total. It is also the largest known uranium deposit globally, although the production rate is tied to the overall flow sheet, and so the target production rate for copper.

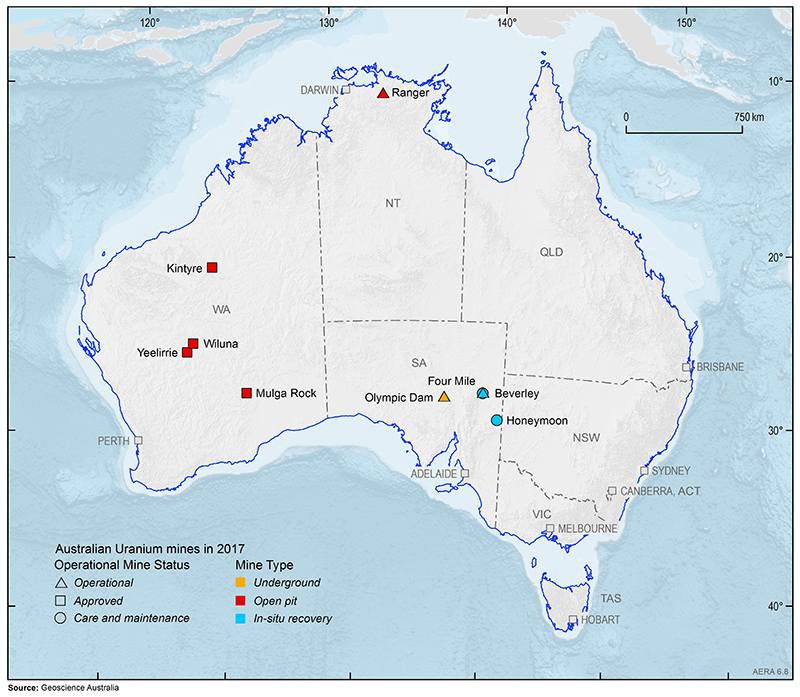

There are a number of other mines that were approved, and never operated, or which operated but then closed due to lower prices, or ore body depletion, see Figure 8.

Note from the map above that all indicated uranium mines are located in Western Australia, South Australia, or the Northern Territory. Uranium mining is illegal in the other states, and prospecting is only permitted in New South Wales. Queensland formerly produced from the Mary Kathleen mine between 1956 and 1963, and again from 1975 to 1982.

There are numerous other formerly operating mines, such as Beverley and Honeymoon. located in South Australia, and the famous Ranger mine in the Northern Territory.

The Politics of Uranium Mining in Australia

The history of Australian uranium mining is one of closures and re-opens due to shifting price dynamics from global demand combined with domestic politics on nuclear policy, and the ever-present geopolitics of nuclear armaments and nuclear non-proliferation policies.

Ranger is now closed, due to ore body depletion, and is under mine-site rehabilitation by the owner and operator ASX: ERA. Honeymoon is under project development for a restart by new uranium producer hopeful Boss Energy ASX: BOE. Mulga Rock was approved but did not proceed due to low prices and is held by developer Deep Yellow ASX: DYL. Wiluna was also approved but never developed and is now held by Toro Energy ASX: TOE.

Yeelirie is one of Australia's largest undeveloped projects. It is now owned by Canadian giant Cameco NYSE: CCJ, who bought it from BHP Group in 2012. It was a greenfield discovery by Western Mining Corporation in 1972, with extensive exploration work completed. This site has been held by Cameco for many years pending an improvement in uranium prices. The same is true of the Kintyre advanced project which Cameco acquired from Rio Tinto in 2008.

Clearly, the uranium market has numerous advanced projects, but the problem has been low prices. Many mines were shuttered in the period where prices fell below $50 USD/lb.

Australia has a developed Uranium Export Policy, which aims at safeguard to distinguish between civilian and military uses of uranium. The original policy stipulated that countries must be parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). However, this policy was changed in 2016 to allow exports of uranium to India, which is not a party to the NPT.

This is a special case. India is a nuclear weapons state, but not a party to the NPT. Formerly, it was excluded from receiving uranium exports. Other nuclear weapons states, that are not part of the NPT, include Pakistan and Israel. Exports of uranium to these states are prohibited.

China can receive exports of Australian uranium because it is a party to the NPT. Since it is a nuclear weapons state, the protocol requires tracking Australian-Obligated Nuclear Material (AONM), as it moves through the nuclear fuel cycle.

Nuclear weapon state customer countries must provide an assurance that AONM will not be diverted to non-peaceful or explosive uses and accept coverage of AONM by IAEA safeguards.

Practically, this policy is likely to remain the case. That may seem odd to some readers, but the protocols for dealing with nuclear materials in a world of civil and military dual use are, by now, very well developed. The Reagan Era dictum: "Trust, but Verify", is the operating principle.

Current Opportunities

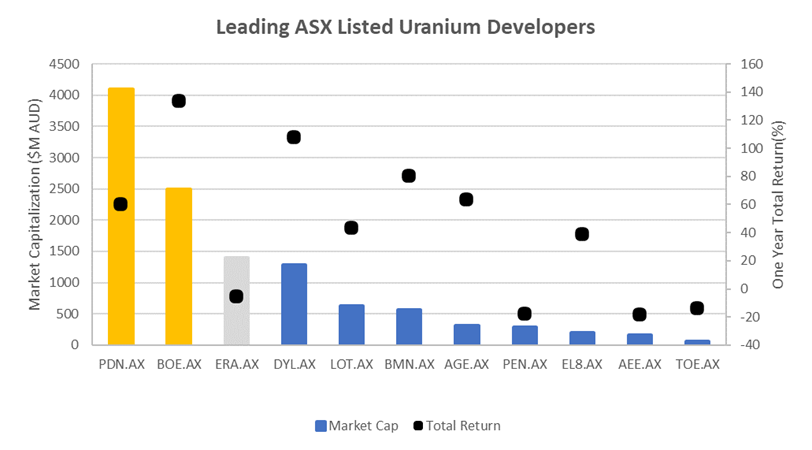

The chart below shows the leading ASX listed uranium developers, with the exception of Silex Systems ASX: SLX, which is a laser-enrichment play, and NexGen Energy ASX: NXG, which has the promising Arrow Project in the high-grade Athabasca Basin of Canada. We think it is best to look at these two firms in the context of North American trends for Uranium.

Considering the forward demand picture for new-build reactors is dominated by developing nations, we must give some thought to policy and treaty driven limitations on export.

Australian mines are (presently) able to export to North America, Europe, China and India.

Our Strategy

Wrapping up this introduction to uranium, we consider that:

- Uranium has entered a structural bull market.

- There are many known discoveries at advanced project stage.

- The near-term winners are likely to be low capex mining restarts.

- The long-term winners may be greenfield projects in secure jurisdictions.

With these facts in mind, our favoured exposures, in addition to ASX: BHP, are the established Western controlled producers, such as Cameco NYSE: CCJ, and low capex formerly producing mine restarts, such as the Langer-Heinrich mine controlled by Paladin Energy ASX: PDN and projects that address cost and social license through In-Situ Recovery (ISR), such as that proposed by Boss Energy ASX: BOE, with their Honeymoon Project restart.

With any exploration boom, there will be plenty of opportunity from new discovery, but the economic potential of a uranium mine is closely tied to pricing and customer offtake.

Firms such as Cameco have very good visibility onto the fuel needs of utilities, and operators like Paladin and BHP have a sound knowledge of the industry channels through which the material is sold, and how best to secure long term cashflows through contracts.

In future wires I will take up the wider global picture for listed companies, plus some of the more interesting midstream and downstream opportunities in nuclear technology.

Image: Nuclear island of HTR-PM Demo Plant. Source: Tsinghua University

5 topics

9 stocks mentioned