It’s tough to be rational

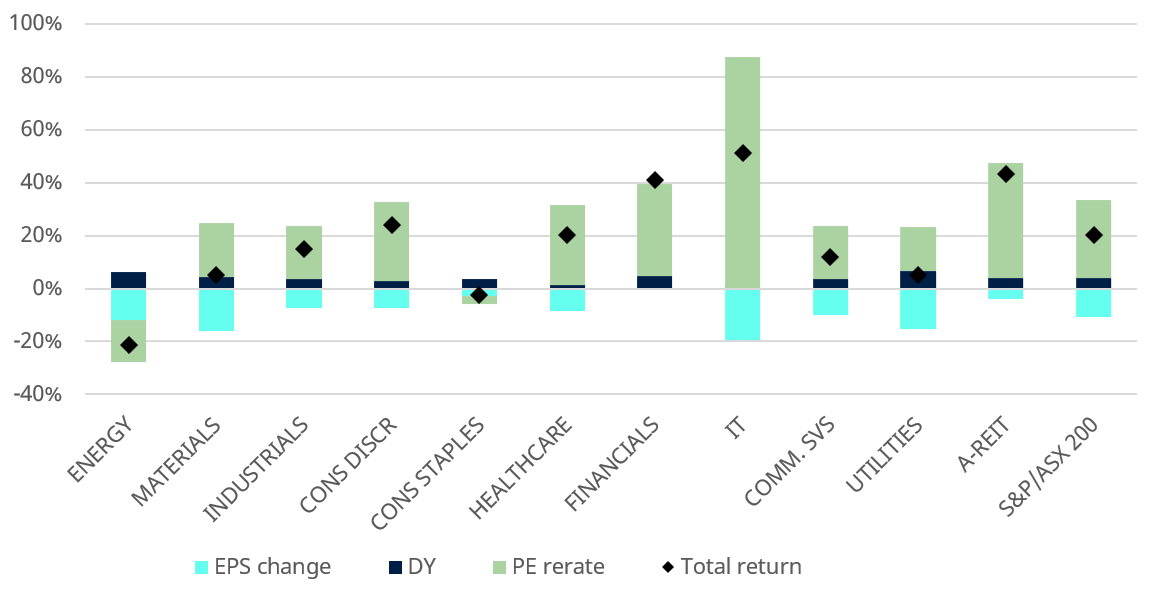

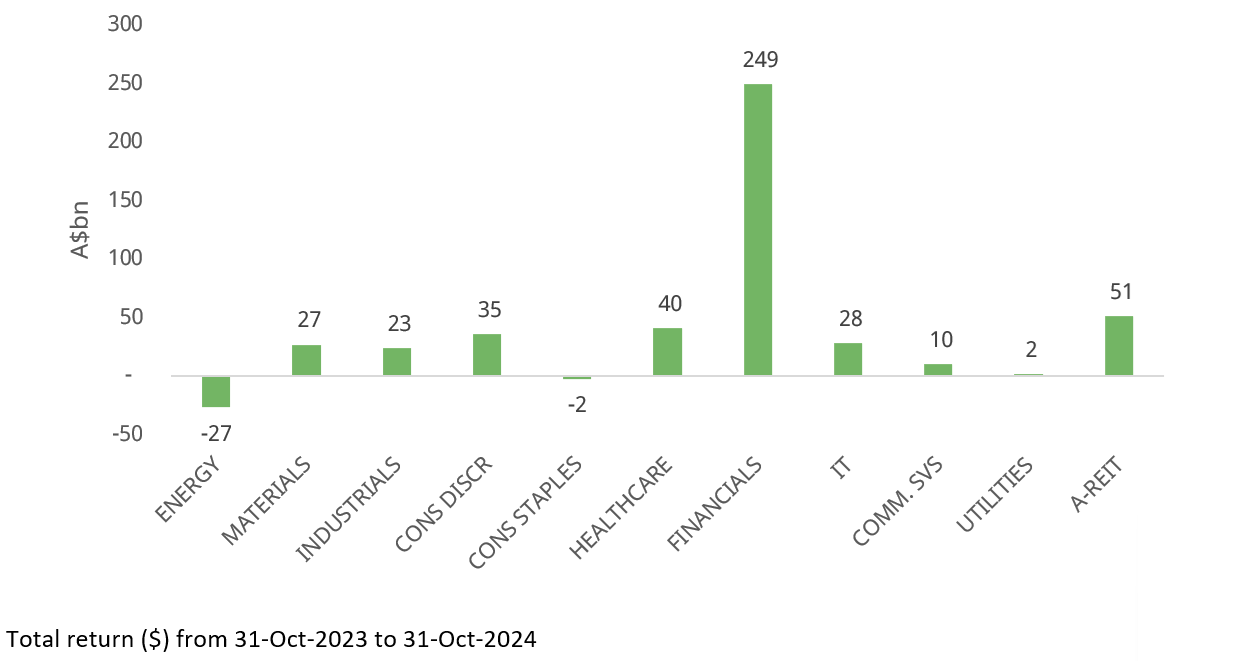

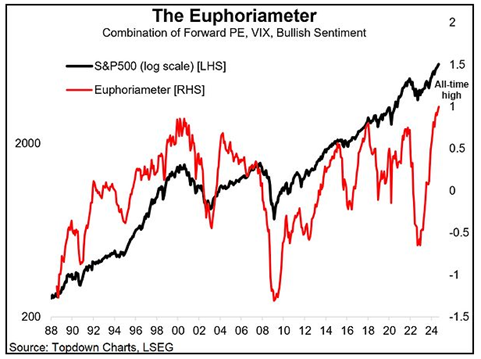

For those of us aiming to apply rationality to equity market investment, life has rarely been tougher. The picture of the past year is regular and torturous. October repeated more of the same. Large elements of the equity market don’t move much at all, financials move steadily higher, and most things technology-related move vastly higher. Earnings changes are explaining very little of the movement in value. The multiples applied to these earnings are explaining a lot. Picking these changes in market emotions has been crucial, given the very large amounts of market value they have shifted. We have been roundly unsuccessful in this endeavour and incredibly surprised at the seemingly crazy extremes to which investors have pushed multiples in some areas. If we were provided all of the facts on earnings movements a year in advance, we are still fairly sure we wouldn’t have gone close to picking the outcomes. Of around $430bn in market value added in dividends and market value changes over the year to 31 October, more than half came in financials, virtually all of this from higher multiples.

The picture across the remaining sectors was mixed, but almost all sectors had downwards revisions to the earnings expectations for 2025. While the increases in market value outside financials look innocuous, the actual earnings supporting the moves were often negligible. The nearly $30bn in additional market value for technology was based on profit growth, which is a rounding error in overall market earnings. The total net profit (not profit growth) of the three largest technology companies on the ASX (WiseTech Global (ASX: WTC), Xero (ASX: XRO) and Pro Medicus (ASX: PME) is about $500m. This $500m supports about $83bn of market value. During October, Metcash (a slightly more pedestrian business in food and hardware retailing and distribution) was savaged after announcing hardware profits were under pressure and overall profit would be slightly down at $130m or so for the half year. Metcash’s (ASX: MTS) annual profits of roughly half of the collective profits of the three technology behemoths support a market value of a little over $3bn. At the multiple of the three tech behemoths its market value would be more than $40bn.

We remain astonished at the preparedness of investors to pay vastly higher prices for possible profits in the future versus actual profits today. Emotions, news and short-term earnings direction remain remarkably powerful drivers of market value.

S&P/ASX200 Total Return Decomposition

Source: Schroders, Datastream, Return decomposition using FY1 expected eps at 31/10/23 and FY1 EPS at 31/10/24.

S&P/ASX200 Total Return

Source: Schroders, Datastream

Expressing somewhat similar emotions, Cliff Asness, the learned founder and CIO of AQR, recently authored a paper contending equity markets have become less efficient over his career. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given I’m looking for reasons to rebut recent evidence of my incompetence, I’m inclined to agree with his conclusions. In particular, Asness suggests a few key takeaways;

- A relatively efficient stock market is important for society

- The stock market has gotten less efficient over his (long) career, and

- Disciplined, value-based stock picking is both riskier and likely more rewarding long term

On the reasons for less efficient markets, Asness suggests a few hypotheses; indexing ruining the market , very low interest rates for long periods distorting investor behaviour, and technology (social media in particular) detracting rather than adding to market efficiency. It is the last he believes to be the most persuasive. Again, I’m inclined to agree. We have discussed previously our scepticism over the current slavish adherence to ‘data driven decisions’. We are drowning in ever more data, given the propensity to collect and store ever greater quantities of it. While there are many instances in which these vast quantities of data will improve outcomes (autonomous vehicles will need to process huge amounts of it), whether more and faster data is the answer to better equity market valuation is more questionable.

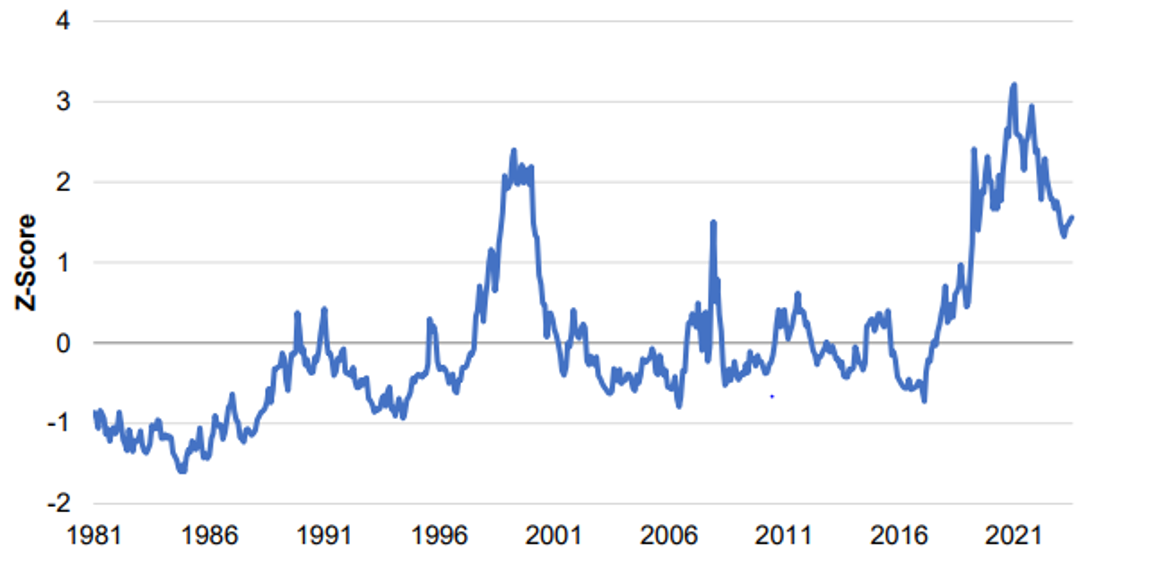

News on earnings, sales, customer satisfaction, commodity prices, freight rates and countless other variables is ordered into alarmingly large databases by powerful data and interface providers such as Bloomberg. It is also now assembled in charts on ‘X’ and countless blogs for vastly lower fees by others. Data availability is unarguably larger and faster. Is it better? Trading speed has allowed high frequency traders to carve out enormous profits by extracting small margins from huge equity market trading volumes, in turn allowing them to pay more for software engineers than almost any other industry and diverting them from more productive uses. We do not believe this has been a positive development for markets or the economy. These profits are effectively a tax on equity trading (paid disproportionately by retail investors). Similarly, investors are now reacting faster and more savagely as they digest more data and noise. Is it improving the accuracy and efficiency of capital allocation? From our perspective, much of our role is determining how much of any new data is already reflected in a company’s valuation and whether a project or business is productively using its existing and incremental capital; not just determining whether the next piece of news is positive or negative, whether we can see a ‘catalyst’ or whether we think the share price will rise in the next few months (otherwise known as guessing). Herding and momentum have become ever more popular strategies, as has waving the flag of being ‘data driven’. As Cliff Asness points out, on almost all measures, the spread between ‘cheap’ and ‘expensive’ is historically wide. Either it’s different this time or speed and data aren’t totally aligned with market efficiency.

"Real life" value spread (intra-industry, 5 measures)

Source: AQR

Outside the continuation of some well-worn market thematics, October was an interesting month for ‘founders’. While piling on the ‘founder led company’ train has been a popular and rewarding strategy over recent years, it isn’t always one way traffic. After all, Donald Trump, Gerry Harvey and Rupert Murdoch are ‘founders’ too. Big egos, erratic behaviour, dubious corporate governance and aggressive risk appetite often accompany the entrepreneurial verve. Richard White (WiseTech Global) and Chris Ellison (Mineral Resources (ASX: MIN)) have both accomplished great things, however, the October newspaper headlines highlight a few of the associated risks. The Boards of both companies attempted to engineer solutions which allowed investors to believe they could retain the entrepreneurial talent while gradually passing over the reins to others. Long-term consulting roles and extended handover periods won’t hide the challenge of replacing powerful and capable personalities with significant ownership stakes. Sometimes it might be best to acknowledge that highly capable founders won’t fit comfortably into the endless policies, paperwork and box ticking which regulators believe will somehow improve company operation. From our perspective it seems far more certain to increase costs and allow management consultants to charge for advice on the succession planning mumbo jumbo that is invariably part of the impossible-to-measure targets in the 40-page remuneration report and convoluted STI and LTI plan to ensure the CEO can make at least $5m. This is, of course, until a peer company of similar size raises remuneration, making it absolutely essential for the Board to raise the remuneration of their CEO in the ‘global war for talent’.

The theme of powerful technology companies, usually controlled by billionaire founders, remains a fascinating and important one for the future of equity markets.

Yanis Varoufakis addresses it in ‘Techno Feudalism – What Killed Capitalism’, providing plenty of food for thought, albeit a little exaggerated at times. As geopolitical tensions heighten and a farcical US election looms, economic risks stemming from companies which have been disproportionate beneficiaries of COVID and monetary stimulus, having been able to ‘clip the ticket’ on vast customer bases and transaction volumes, and access the enormous amounts of customer data on which their businesses rely without paying for it or investing much capital, are coming into focus. In particular, as these businesses play an increasing role in the financial system, facilitating huge volumes of cross border transactions, paying little tax and heavily influencing the views of the general population, threats to the economic control of governments are perhaps not wildly exaggerated. While skyrocketing bitcoin and gold prices send a concerning message on deteriorating confidence in government monetary control, creeping reliance on foreign manufacture facilitated by impressive technology and logistics platforms highlight a few risks in the physical economy which aren’t often thought about by enthusiastic technology investors. As Jim Farley, the CEO of Ford recently commented in talking about Chinese auto manufacturers, “These guys are ahead of us”. Complacency is dangerous.

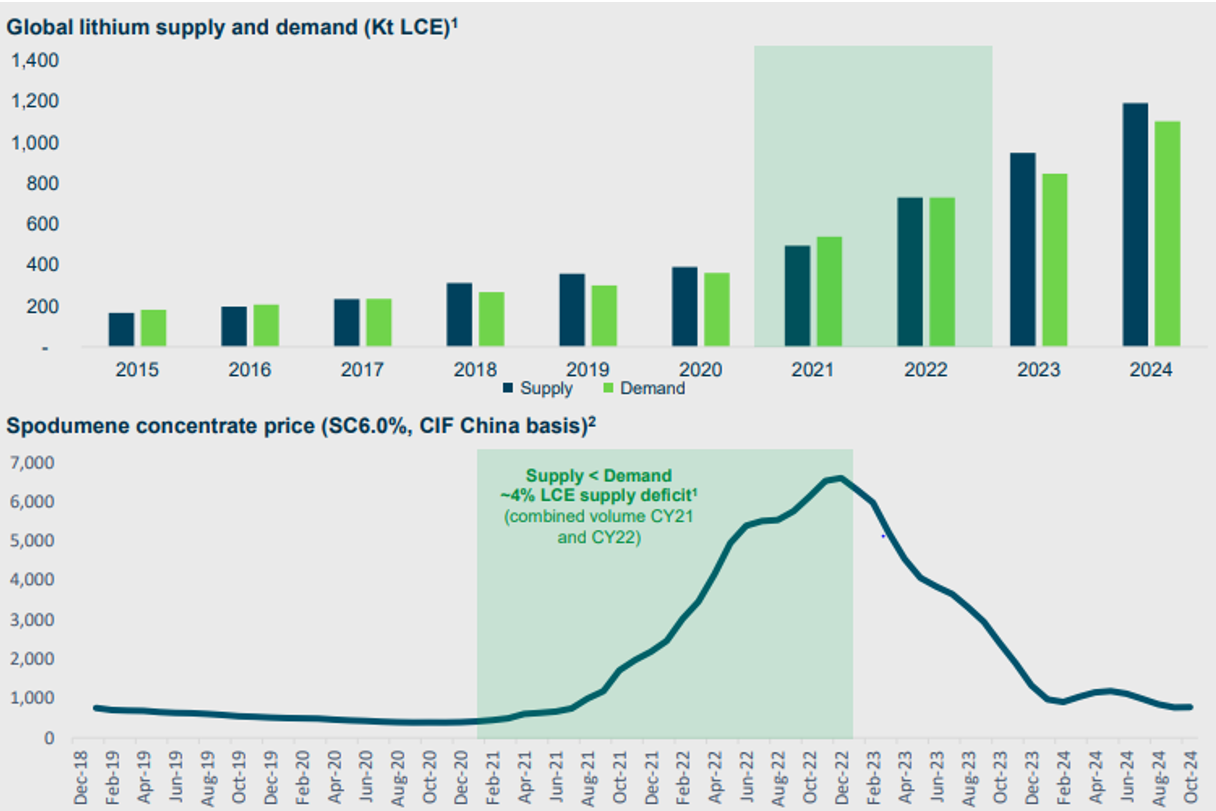

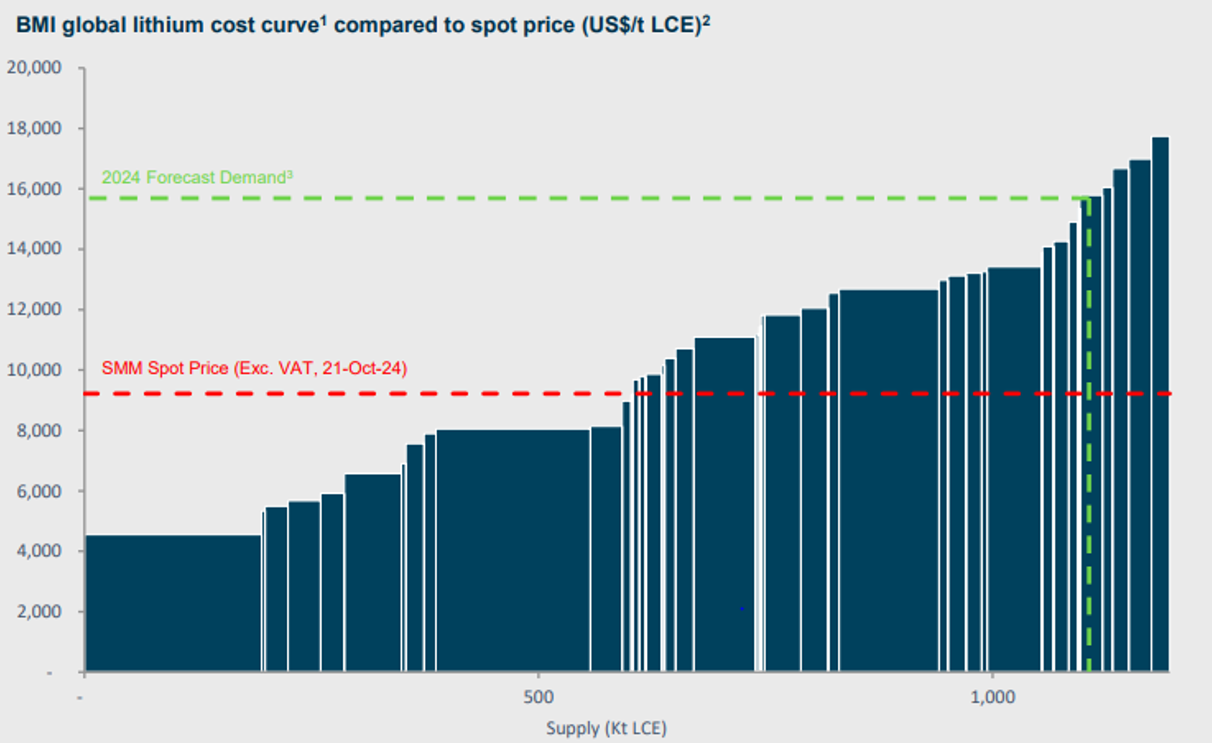

As materials and Chinese exposures remain widely shunned, Rio Tinto’s (ASX: RIO) US$5.85 bid for Arcadium Lithium (the product of an only recently concluded merger between Allkem and Livent) could be touted as a counter cyclical play. There is little doubt the industry is facing challenging conditions. Even fairly low cost players like Pilbara Minerals (ASX: PLS) are reducing production and focusing on capital conservation and cost reduction. Current prices are well through the cost curve on most measures. While the timing is intuitively conducive to M&A activity which could potentially add value rather than destroy it (as is far more commonly the case), there are a few more concerning aspects. As is often the case for large players such as Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton (ASX: BHP), their desire for ‘agreed’ deals in which the Board of the target company agree and recommend the deal, comes at high cost. The 94% rise in the Arcadium Lithium share price in October is this cost. Target companies are more than aware of their desire to avoid acrimonious and drawn out negotiations. Very large acquisition premia are the cost of avoidance, transferring plenty of value from the acquiror to the acquiree. Secondly, the relatively immature nature of the lithium industry means the long-run price, always the major driver of underlying value in a commodity business, is not easy to determine.

As the Pilbara Minerals chart below indicates, outside the 2021 and 2022 period of heightened demand pressure, the spodumene price has spent most of its history at or below US$1,000.

Source: Pilbara Minerals September Quarter Activities Presentation

While the equivalent lithium carbonate (LCE) price depends on views of sustainable conversion costs, freight etc., prices at the US$15,000- $16,000/t LCE level to match the Benchmark Minerals forecast demand level probably mean spodumene prices around US$1,100 – 1,200, still well below the long run prices used by most analysts. As supply from Africa has continued to grow, we remain a little concerned long-run price expectations still retain some boom time influence. Lastly, as a dominantly South American business, we remain puzzled at the extent to which companies and analysts are prepared to adopt developed market multiples in assessing value. When the gap between bond yields in these jurisdictions and developed markets is wide, it is arguable how significantly equity discount rates should vary. Zero doesn’t seem the right answer. These concerns aside, we would maintain the likelihood of destroying significant value is vastly lower than buying in times of euphoria. The euphoria of today does not tend to be in mining.

Source: Pilbara Minerals September Quarter Activities Presentation

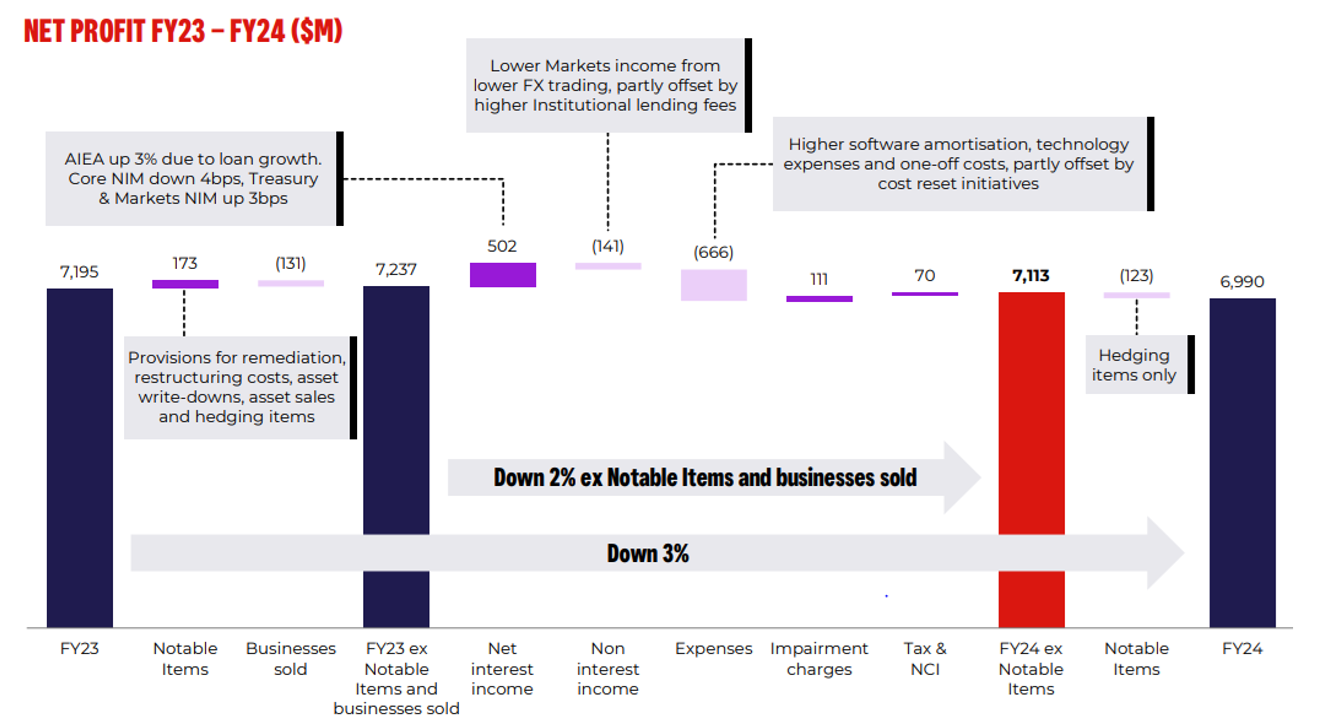

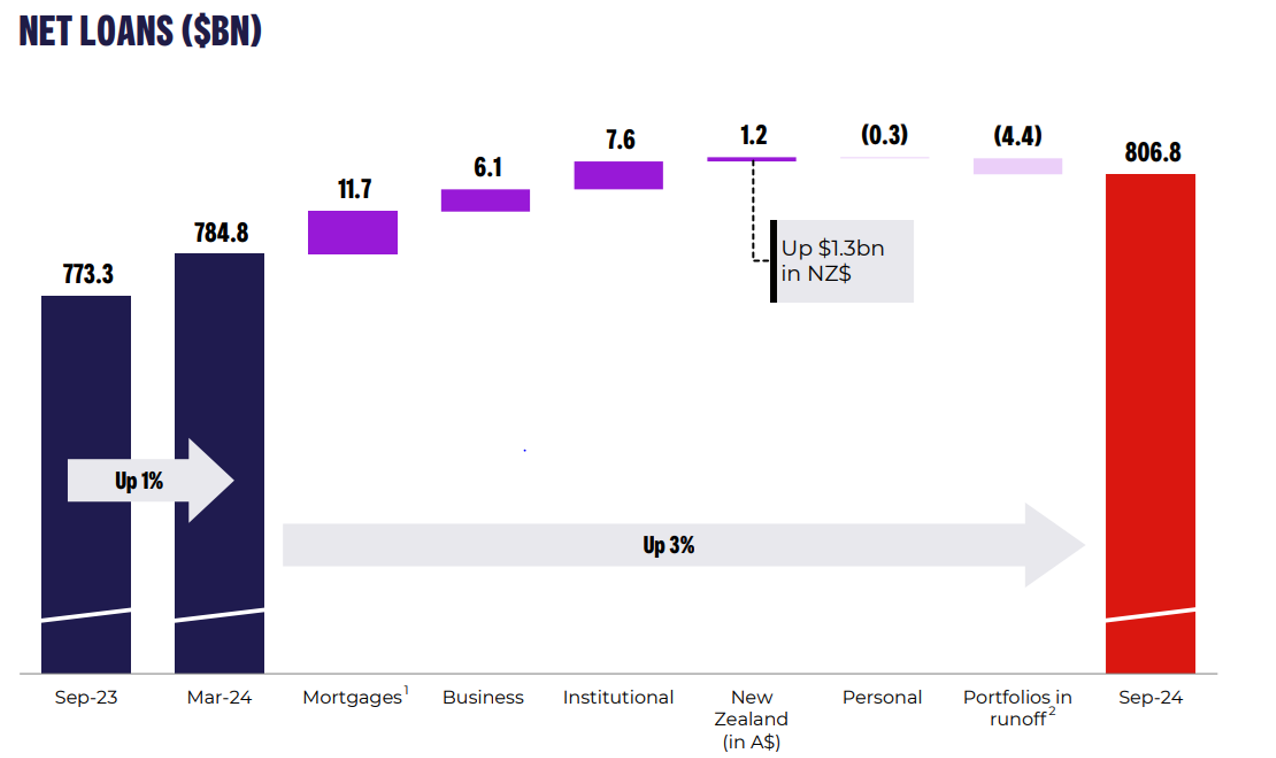

Speaking of euphoria, while mining is where it isn’t and technology is where it is, banking remains in the confounding middle ground. Positioning in the sector has been costly in relative performance terms and we continue to try to understand whether we have made grievous errors or whether this performance is transitory. The Westpac (ASX: WBC) annual result has provided us some incremental data on this front. The picture remains fairly consistent; pre-provision operating profits are fairly flat, with still growing loan balances and fairly flat net interest margins delivering minimal revenue growth. Operating expenses remain on a higher trajectory than revenue and negligible bad debts are rescuing the net profit line. As stressed exposures continue to rise while bad debt charges fall, it seems difficult to believe an economy with extremely high levels of housing leverage can translate into one with no bad debts in perpetuity, particularly as house prices have stopped rising. In line with the earlier described trends towards valuation gaps which we struggle to explain, though Westpac financial performance remains slightly inferior to that of CBA (ASX: CBA), we struggle to transform a balance sheet of very similar size and structure and profit and ROE about 25-35% below the market leader into a bank which is worth less than half as much. The more momentum inclined investors might call it a ‘quality premium’. We’re a little more inclined to side with market inefficiency. Removing the multiple differential between CBA and Westpac would see about $90bn or 40% wiped off the CBA valuation.

Market outlook

Maintaining rationality isn’t getting any easier. The durability and regularity with which the same thematics have dominated market performance add greatly to the challenge. Whether you’re playing a sport or running a business, losing a lot is draining. When it comes to data sets for listed equity market investors we have one vast and rich one; share prices. Measured every micro second and used to determine the value of every holding, they are the most important in driving emotions. Those which provide more reliable yardsticks of value are provided far less regularly in the form of earnings reports and audited accounts. Even these are subject to interpretation and manipulation. A lot goes on between ‘adjusted EBITDA’ and reported Net Profit After Tax. Multiples are the link between the earnings and the share prices. We have stood by as these multiples have seemingly lost their grounding as considered discount rates on sensible expectations of the future and become slaves to the next piece of ‘data’ and expected share price direction. Adhering to fundamentals has been far more painful than in years gone by.

Overall measures of valuation remain extended, while most measures of investor sentiment would suggest now is a time for great caution. Nevertheless, as the market valuation increments referred to earlier illustrate, this euphoria has been narrow in its focus, with large segments of the equity market relatively unaffected. Staying rational has rarely been more difficult, but possibly never been more important.

Learn more about investing in Schroders' Australian Equities here.

10 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned