Looking to the East – A lesson from Japan

Yarra Capital Management

In 2011 a dramatic shift occurred throughout the developed world — working-age populations began a multi-decade decline. Demographic shifts in an economy like this can have profound effects on economic factors, leading to changes in growth and debt metrics. This three-part series explores:

- the economic impact in simple terms using insights from Japan, which was the first economy to undergo the demographic shift

- how an ageing population can influence government debt levels

- how the top 10 developed nations respond

- the knock-on effect for inflation and interest rates.

Part 1: Looking to the East – A lesson from Japan

From a demographic perspective, the developed world changed in 2011 when a population tailwind turned into a headwind. The yearly change in working age population (those aged 15 – 64) across the developed world went from a clear positive to a consistent negative as there will be approximately two million fewer people aged 15-64 in developed economies every year for the next two decades. Given this has been a relatively recent shift (the Baby Boomers generation started retiring in 2011) the complete economic effects are still being debated. Despite this, we can look for clues from Japan, the one country that started this process in the mid-’90s.

"There will be approximately two million fewer people aged 15-64 in developed economies every year for the next two decades"

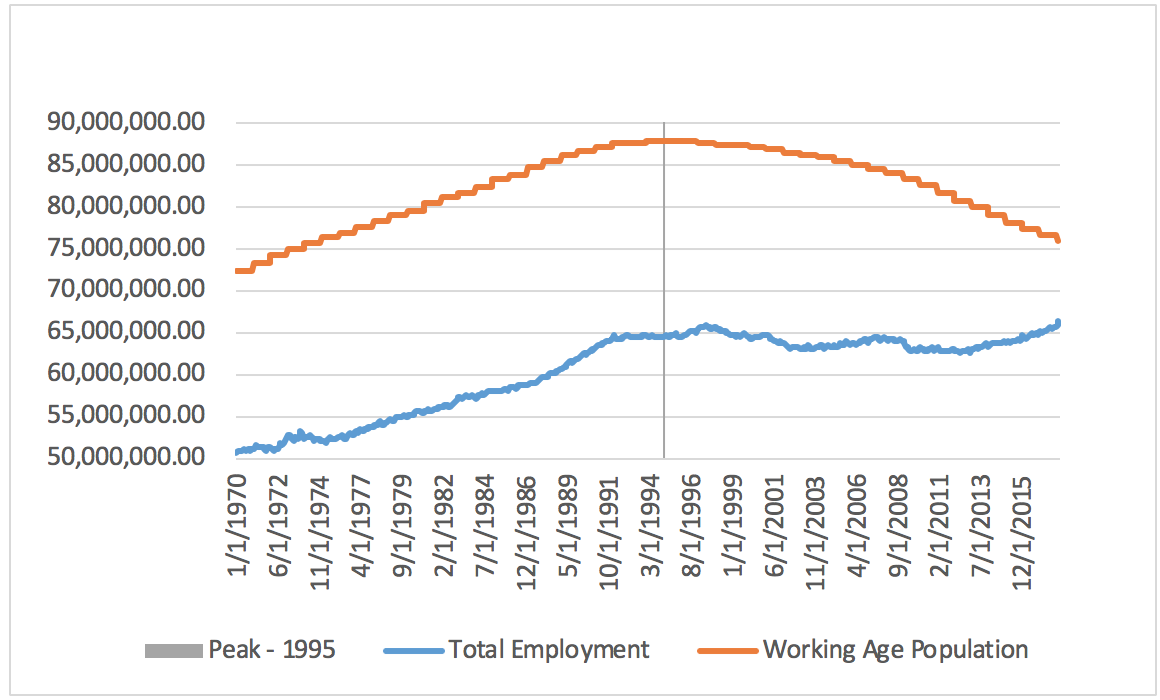

If we look at Japan their working-age population stagnated and begun to decline in the mid-’90s — coinciding with a period of non-existent employment growth. This is an important observation to make, as the amount of production that an economy can achieve is related to the number of workers in the economy when employment growth slows so too does economic growth.

As the working-age population declines, this means it will be harder for an economy to recruit new workers as the typical 15 – 64-year-old cohort is declining, and without new workers, an economy must rely on productivity growth to get larger. This raises an important question: how can we slow or stop this decline as the developed world enters a period of negative working-age population growth?

Chart 1: Working age population and employment - Japan

Source: United Nations DESA Population Division, Bloomberg

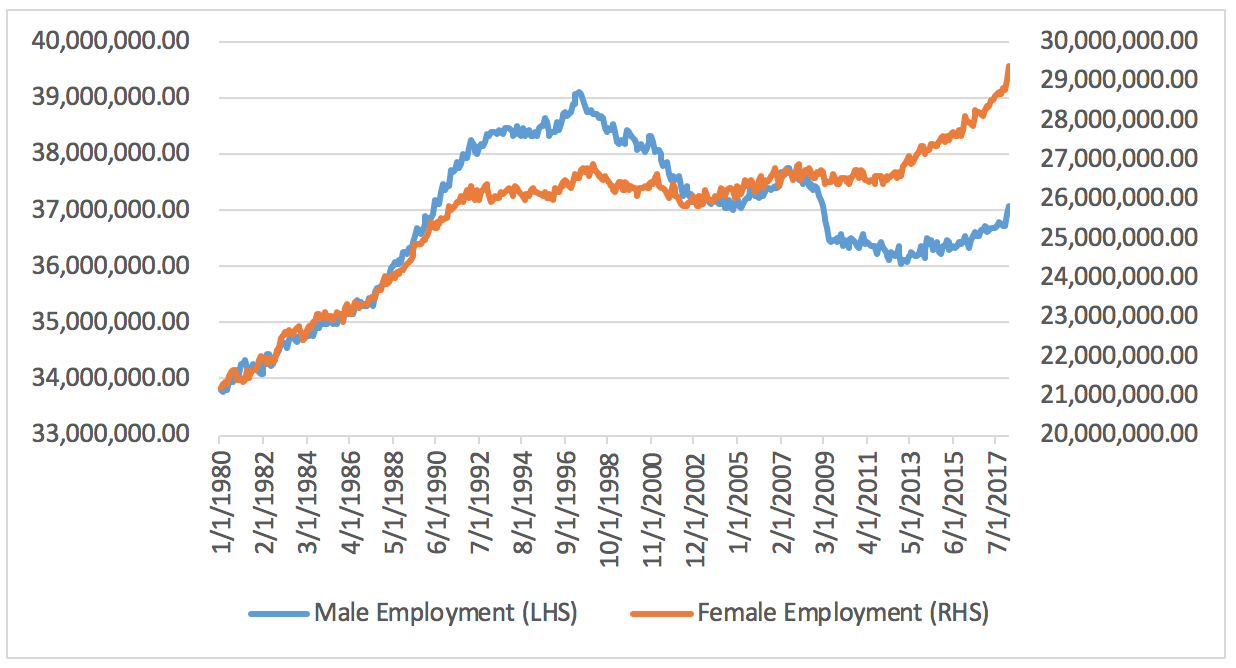

As can be seen in Chart 1, despite a continued decrease in the working age population, total employment in Japan began increasing in 2012. This timing coincided with the introduction of ‘Abenomics’ — a three-pronged policy approach implemented by the Japanese government. Part of this policy included structural reform designed to encourage women to enter the workforce to address the traditionally low employment rate of Japanese women. This policy allowed the Japanese workforce to grow by tapping an underutilised part of the economy, bringing signs of life back into the workforce, which had not been seen for the better part of 20 years.

While an increase such as this cannot continue in perpetuity since the working age population will continue to decline, it can help soften the blow of demographic changes and improve growth over the short to medium term as a new source of employment is found.

Chart 2: Employment by gender - Japan

Source: Bloomberg

This response highlights the importance for governments finding structural reforms and incentives that encourage workers to enter or remain in the labour market, offsetting the effects of a declining working age population. Since the working age population started declining it has become harder for Japan to increase the number of people available to produce goods in their economy. Overall this has caused the potential GDP growth of the economy to slow and now requires good planning and structural reform from the government to increase its workforce, rather than just relying on a natural increase over time.

The lesson for other developed nations should not be that Japan’s experience with the lost decades is an isolated problem. But rather if an economy is facing a structural reduction in its workforce due to a decline in its working age population, what policies could be used to encouraged greater employment from the traditionally lower employed cohorts.

Part two: how an ageing population can impact government debt

Further insights

For additional analysis and insights from the team at NIkko Asset Management, please visit our website.

2 topics

Chris is responsible for portfolio management, including portfolio construction and trading for various Australian fixed income portfolios including the Nikko AM Australian Bond Fund at Yarra Capital Management (Nikko AM was acquired by Yarra...

Expertise

Chris is responsible for portfolio management, including portfolio construction and trading for various Australian fixed income portfolios including the Nikko AM Australian Bond Fund at Yarra Capital Management (Nikko AM was acquired by Yarra...