Magnificently concentrated

Patience is widely understood to be a virtue in investing. Many clients and investment committees pride themselves on their willingness to stick with high-conviction managers through rough patches in performance in the belief that given sufficient time, the skill will tell. But even patient investors have their limits, and this fall we saw an avalanche of questions coming in from institutions as to whether it is time to abandon active management, at least in US large caps. We were a little surprised by this since our US large-cap equity products have actually done well against their benchmarks over the last few years. (1) But a little digging made us realise that most clients’ experience with their active US equity strategies has been pretty disappointing.

According to Morningstar, 74% of U.S. large-cap blend managers underperformed the S&P 500 last year. And it wasn’t just a single bad year. The decade ending in 2023 saw a stunning 90.2% of US large-cap blend managers underperform their benchmarks.

After a brief respite for active managers in 2022, when 53% of U.S. large cap blend managers outperformed, it seems as if 2023 may be the last straw for many clients. How can you blame them? A decade is a lifetime in the investment world. If 90.2% of managers underperformed their benchmarks in U.S. large caps over the last decade, surely that is irrefutable evidence that the market is efficient?

The reality is somewhat different, however. As we will see, the reason why the S&P 500 and other US large-cap equity benchmarks have been close to impossible to beat over the last year – and almost as hard to beat over the last decade – stems from the nature of the stocks that have outperformed.

The US equity market has been growing steadily more concentrated. When the very largest stocks are the best-performing ones, it is an extremely difficult environment for active managers to keep up with, let alone outperform. To outperform an index, it is necessary to look different from it.

We tend to think of that difference in terms of the stocks that a manager owns, but as Cremers and Petajisto’s active share measure points out, what managers choose not to own is just as important as what they do own. (2)

To make space in a portfolio for the stocks a manager wants to be overweight, they by necessity must have an equal and offsetting underweight in other stocks. While active share envisions this as running a long/short portfolio on top of the benchmark, the reality is that it is a highly constrained long/short. A manager can choose to be as overweight as they would like in their favourite stocks, but the underweights for a long-only manager are constrained by the weights of those stocks in the benchmark. (3)

The biggest underweight for a manager will not be their least favourite stock, but the largest stock in the benchmark that they don’t like enough to have a substantial weight in. The upshot is that long-only active managers almost always have a substantial bias against the very largest stocks in their benchmarks. This is particularly true of the extremely high active share “high conviction” managers beloved by endowments and foundations, who commonly have active shares in the 95% range. (4)

For most of history, biasing portfolios against the very largest stocks has been lucrative. But over the last decade, and particularly the last year, it has been a disaster.

A narrow decade

If you look at the 10 largest companies in the S&P 500 (or any capitalisation-weighted index, for that matter), odds are that the stocks of those companies meaningfully outperformed the broad market over the preceding decade. The largest companies in the world either started out large and kept up with their competition, or they started small and outperformed almost everyone larger. This was certainly the case over the last decade.

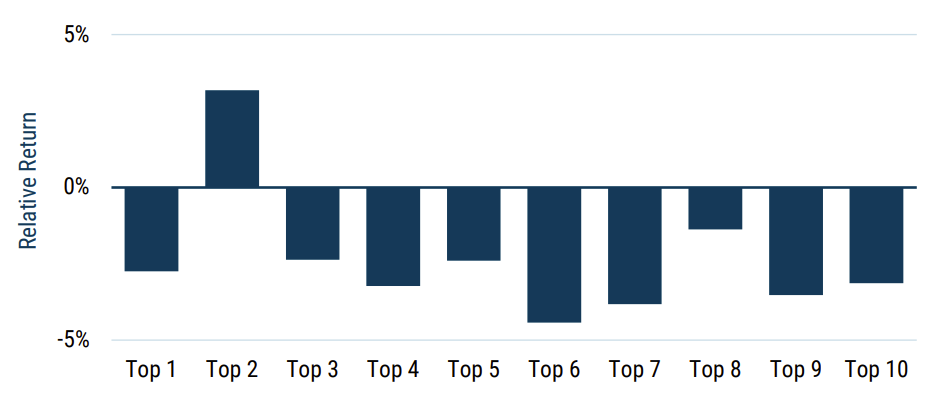

On a forward-looking basis, however, big is generally anything but beautiful. Exhibit 1 shows the relative return of the 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500 in the year following that ranking.

Exhibit 1 - Top 100 stocks vs S&P 500

Data from 1957-2023 | Source: Compustat, Standard & Poors.

Nine of the top 10 have underperformed on average. (5) The historical underperformance of the top 10 comes down to the two main sources of return – valuation expansion and fundamental growth – being harder to achieve than for your average company. The largest stocks generally become the largest by way of becoming expensive, and this anti-value tilt has historically been quite costly, explaining most of these companies’ poor relative returns. (6) Good returns in the face of high valuations, moreover, require exceptional earnings growth. When a company already has a substantial market and profit share of the industries in which it operates, unusual growth tends to be significantly harder than normal. It can be particularly hard if the company’s growth catches the attention of anti-trust regulators.

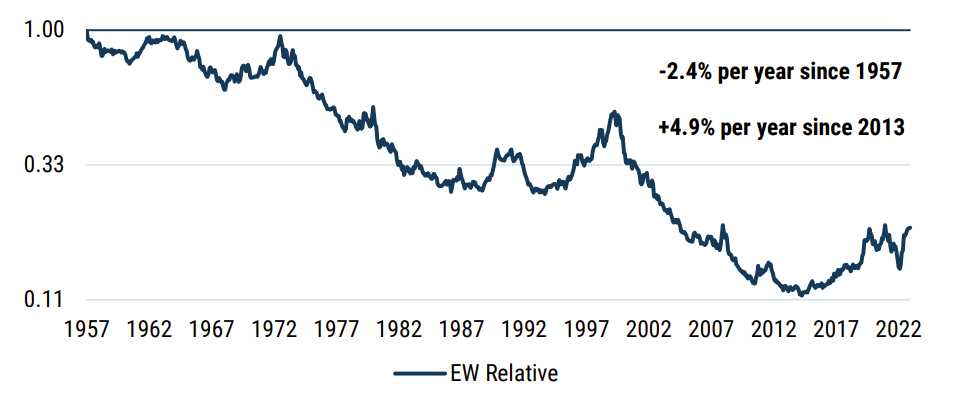

The largest stocks certainly don’t underperform all of the time, but on average, they have substantially trailed the average S&P 500 stock, as we can see in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: S&P500 – Top 10 VS. 490 equal weighted

Data from 1957-2023 | Source: Compustat, Standard & Poors

Since 1957, the 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500 have underperformed an equal-weighted index of the remaining 490 stocks by 2.4% per year. But the last decade has been a very notable departure from that trend, with the largest 10 outperforming by a massive 4.9% per year on average.

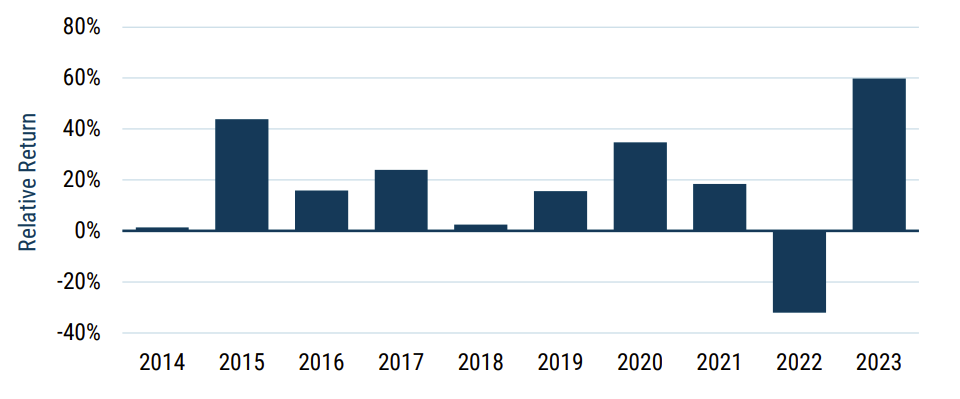

Magnificent and concentrated

The break in the consistent downward trend of cap-weighted underperformance reflects the magnificence of the Magnificent Seven. (7) As far as mega caps go, they have been practically unparalleled in their outperformance. They strung together a series of market-beating performances over the last 10 years, with 2022 being the single year in which they didn’t beat the market. In 2023, as their monicker became part of the common lexicon, they outperformed the S&P 500 by an almost unimaginable 60%.

Exhibit 3: The magnificent 7 vs. the S&P 500

Data from 2014-2023 | Source: Compustat, Standard & Poors

This performance came in part from the unusual cheapness of mega caps at the start of the decade. Apple, Microsoft, and Google, for instance, boasted a combined price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 15x in 2013, while the market’s P/E was about 25% higher. A simple reversal of this trend was a lovely tailwind (although much more than a reversal occurred).

These companies, alongside their similarly magnificent brethren, also managed to grow earnings at a breakneck pace. Microsoft and Amazon did so by reinventing themselves. Apple, Alphabet, Meta, Nvidia, and Tesla took over their primary industries. The medium-sized businesses among them became huge, and the large ones became giants.

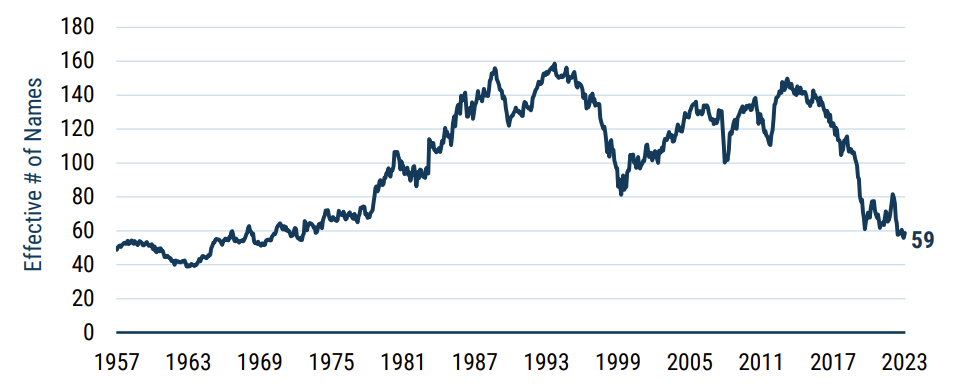

The continued, unrelenting outperformance of very large companies has led to the S&P 500 becoming significantly more concentrated over the decade. The top seven names in the index comprise 28%, up from 13% a decade earlier. The S&P 500’s total concentration, which we can measure using a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (or HHI), is equivalent today to that of an equal-weighted, 59-stock portfolio. Ten years ago, the index was more than twice as diversified. We have never seen – over any 10-year period – a decline (or increase) in diversification of the magnitude we have just witnessed.

EXHIBIT 4: EFFECTIVE # OF NAMES (1/HHI) IN THE S&P 500

Data from 1957-2023 | Source: Compustat, Standard & Poors

The active horror show

This extraordinary performance of the mega caps and the consequent concentration of the S&P 500 seems to have become conflated with markets becoming more efficient. This conflation occurs because over the same decade that appended “Magnificent” to “Seven,” only 9.8% of U.S. large cap “core” active managers outperformed their benchmarks. (8) While these events are certainly connected, they in fact have very little bearing on market efficiency (a topic which we plan to broach in our next Quarterly Letter).

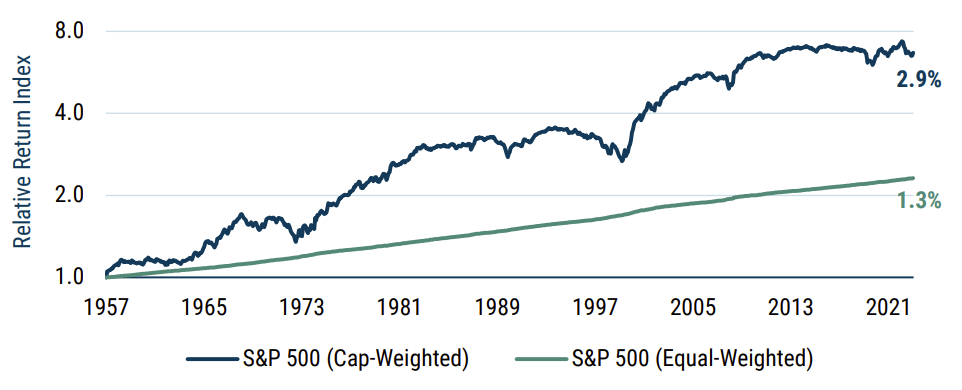

Because the vast majority of active managers are substantially underweight the largest stocks, periods when those stocks outperform are a serious headwind for active managers’ relative performance. If we contrast the equal-weighted vs. cap-weighted performance of the S&P 500 with the annual percentage of U.S. large cap core active managers outperforming their benchmark from 2014 to 2022 (according to Morningstar), we find that the correlation of these (admittedly short) two series is north of 50%.

While Morningstar has not yet published its results for the full year of 2023, the equal-weighted S&P 500 trailing its cap-weighted counterpart by 11.5% (the second worst showing of all time) suggests that investment committees will have their brows furrowed when reviewing their U.S. active equity portfolios’ performance vs. the S&P 500 over the last year. Some brow-unfurrowing might be merited. High active share managers have almost no chance in a year when the giants are dominating. (9)

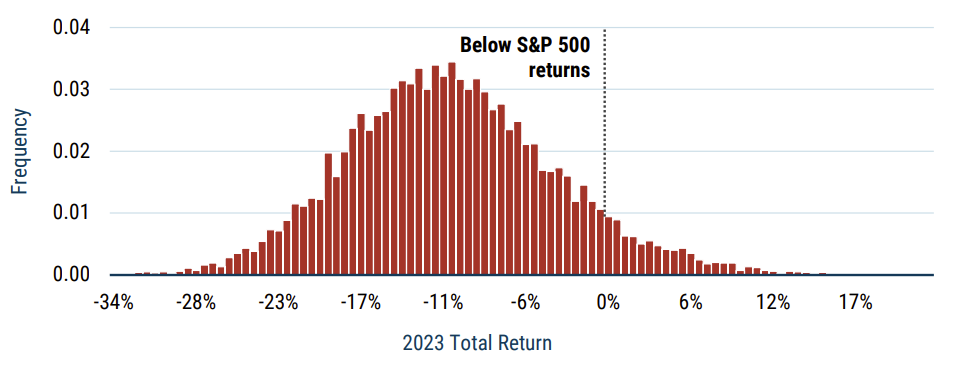

To show just how difficult an active manager following the concentrate-and-equal-weight strategy would have it, we simulate what a talented set of managers could have achieved versus the cap-weighted benchmark. These simulated managers have a consistent hit-rate of 53%; that is, each of their stock picks has a 53% chance of beating the average stock in the S&P 500 over the 12 months following their selection. This might not seem like a great deal of prescience, but it really is. This group of managers, by picking 20 stocks and equally weighting them, would have outperformed the S&P 500 by 3% per annum from 1957 to the end of 2023, generating cumulatively for their investors six times the return of the index. They would have beat the index two thirds of the time. Their worse performance as a group through 2023 would have yielded them a relative return of -13.6% in 1998. (10) This is a pretty exceptional return profile.

Exhibit 5: Oracle managers vs. S&P 500

Source: GMO, Standard & Poors

The 10 years ending in 2023 were less kind to our oracular stock pickers. Despite exceptional relative returns of 8% in 2022, the group still lost to the S&P 500 by 30 bps per annum (before fees!). In 2023, only 7% of our simulated skilled managers would have beat the cap-weighted index. An investment committee that sought out fundamental managers that roughly follow our described investment process is then exceedingly unlikely to have seen its listed equity bucket shoot the lights out, and it should be comfortable with that. The reality is that these managers still had strong performance against the equal-weighted S&P 500 – and that is what they should be contrasted with in good times and in bad. If your fundamental active manager keeps lagging versus the equal-weighted S&P 500, that is suggestive of an issue; lagging the cap-weighted benchmark is, for such managers, generally uninformative.

Exhibit 6: 2023 performance – Oracle active managers

Source: GMO

A note to the investment committee

Diligent investing requires measurement, and measurement requires appropriate benchmarks. Market capitalisation-weighted benchmarks such as the S&P 500 have several useful features. They require relatively little trading, so their performance reasonably matches that of an actual portfolio managed to track them. They encompass the opportunity set for investors as a whole – all investors could simultaneously hold a market capitalisation-weighted index of global stocks. But they aren’t perfect.

As we have detailed, the cap-weighted S&P 500 is a rather awkward index today; it looks like a 70/30 split of a regular index with 493 companies and seven enormous, often expensive businesses. The top seven are no longer cheap in aggregate, boasting a P/E of 37x (vs. the market’s 25x). One reason to want to own them, however, is their quality; these companies have very deep moats. It’s hard to compete with Apple on brand value, and it’s harder still not to have the company benefit from anyone’s success in its App Store.

Alphabet and Meta are the two unassailable names in advertising, and they have both been extremely successful in acquiring potential competition.

Amazon and Microsoft have essentially "duopolised" cloud infrastructure. They have also been successful in monopolising many a sub-industry.

Nvidia has repeatedly outclassed AMD and become the world’s main GPU manufacturer at the convenient moment when GPU demand has exploded due to advances in AI.

And Tesla…makes pretty cool cars. Less of a moat, and a spicy valuation, but that’s beside the point.

Six of the Magnificent Seven are high-quality businesses and deserve to trade at a premium.

Their premium is stretched, though. Even at their quality, this level of expensiveness normally represents a 2% drag for the companies that carry it; a cost that cheaper high-quality companies in the S&P 500 don’t have. A diversified basket of high-quality names also has less idiosyncratic risk. The proportion of stock-specific risk in a portfolio is roughly proportional to its total concentration, and the S&P 500 is therefore in the uncomfortable position of suddenly having individual lawsuits, factory strikes, and CEO changes driving a not unsubstantial portion of its return variation.

Common risks across the Magnificent Seven should also be a source of unease. They are all reliant on the general availability of semiconductors, most of them have considerable investments in AI, four of them have ties to Foxconn, and their average revenue exposure to China and Taiwan is close to 20%. A geopolitical event that hurts U.S. companies’ access to China, Taiwan, and the semiconductor industry would therefore be profoundly uncomfortable for this group of companies. Investors who are averse to the 4% combined weight of China and Taiwan in MSCI ACWI should be mindful of the 17% combined weight of the U.S. superstars in that same index.

Time will tell if the Magnificent Seven turn out to be as fallible as the Nifty Fifty or the TMT darlings that preceded them at other notable times of mega-cap outperformance. But the history of mega caps when they are trading at a substantial premium to the rest of the market is particularly poor.

If the US equity market becomes less concentrated – our bet for the next decade – skilled active managers are poised to have a decade for the books. Allocators who stick to basics, reminding themselves of the virtues of diversification, stand to benefit handsomely.

1 topic

7 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned