Make Australia Gold Again!

Gold prices have steadied in the last few trading days, after correcting over the last month in the face of a rallying USD, and a sharp unwind in speculative positions.

Technical and sentiment indicators suggests the metal is due for a bounce, which could occur alongside further strenght in the dollar, especially if recent developments in Italy escalate into a proper "risk off" event for markets.

Short-term movements aside, we wanted to share a edited version of a detailed piece of research we've put together over the last month, looking back at a decision made 21 years ago by the Reserve Bank of Australia to sell off the vast majority of Australia's gold reserves.

A look back at the 1997 RBA Gold Sale!

One can only imagine what sentiment towards gold was like back in the late 1990’s, when it was languishing below AUD $500oz, having suffered a near double decade bear market. No yield, ongoing storage costs, and significant opportunity cost does not a happy investor make.

It wasn’t just investors, with central banks net sellers of the metal from the late 1980s right through to the onset of the GFC, divesting close to 6,000 tonnes over this 20 year time frame.

One of those central banks was the RBA, who back in 1997, sold off roughly two-thirds of Australia’s national gold reserves, netting some AUD $2.4 billion in the process.

What Was the RBA Thinking at the Time?

The rationale for the RBA gold sale was explained in a very detailed memorandum prepared in December 1996.

The memorandum noted that gold represented some 20% of foreign exchange reserve assets, and that there was considerable cost of holding this reserve, especially in terms of income foregone.

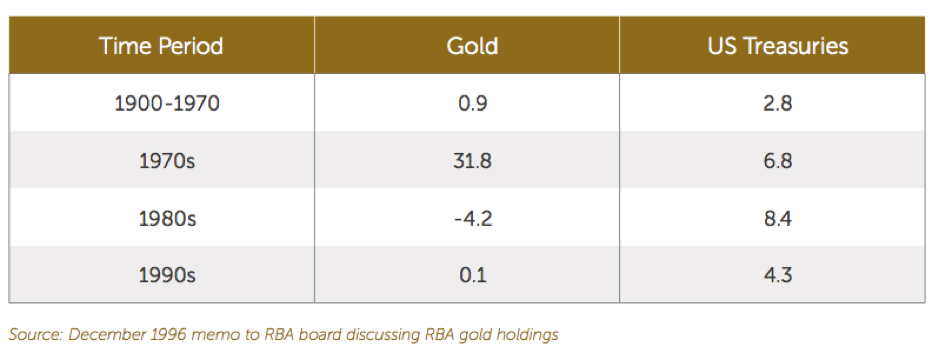

When looking at the outlook, the memorandum noted that; “it would be optimistic to expect sizeable increases in the price of gold in the near term”, and included the table below, which contains the returns on physical gold vs. US Treasuries.

Compound Annual Returns (Percentage)

This analysis was partly used as justification for the gold sale, with the memorandum stating that; “The value of $100 invested in US Treasuries in 1900 would now be about $3,700 (assuming all coupons were reinvested), which is about twice the value of a similar investment in gold”.

Whilst the data is accurate, the insight drawn was questionable at best, for the memo itself noted the gold price was fixed up until 1971. Had those preparing this memorandum stripped out the 70-year period where gold prices were fixed, then the return comparison of gold vs. treasuries would have come out in a much better light, as it was in fact the yellow metal that more than doubled the performance of treasuries, not the other way around.

Impact of the Physical Gold Sale!

Had the RBA held onto the gold, those 167 tonnes would be worth closer to AUD $9.4 billion today. In simple terms, the decision to sell at an almost double decade low has cost some AUD $7 billion in capital gains foregone.

In fairness to the RBA, we must acknowledge the growth of the proceeds they received for the gold sale. Given the duration profile of their assets, and the countries they invested in, we’ve used the return on 2 year US Treasuries between March 1997 and March 2018 as an (admittedly rubbery) estimate of what the money would be worth today.

Based on an annualised return of 2.54%, the proceeds of the gold sale would be worth some AUD $4.07 billion by now, meaning the decision by the RBA to sell back in 1997 has likely set the nation back closer to AUD $5.3 billion in the years since.

But we can’t go back in time, and the most important thing to focus on is what they should be doing now.

Make Australia Gold Again

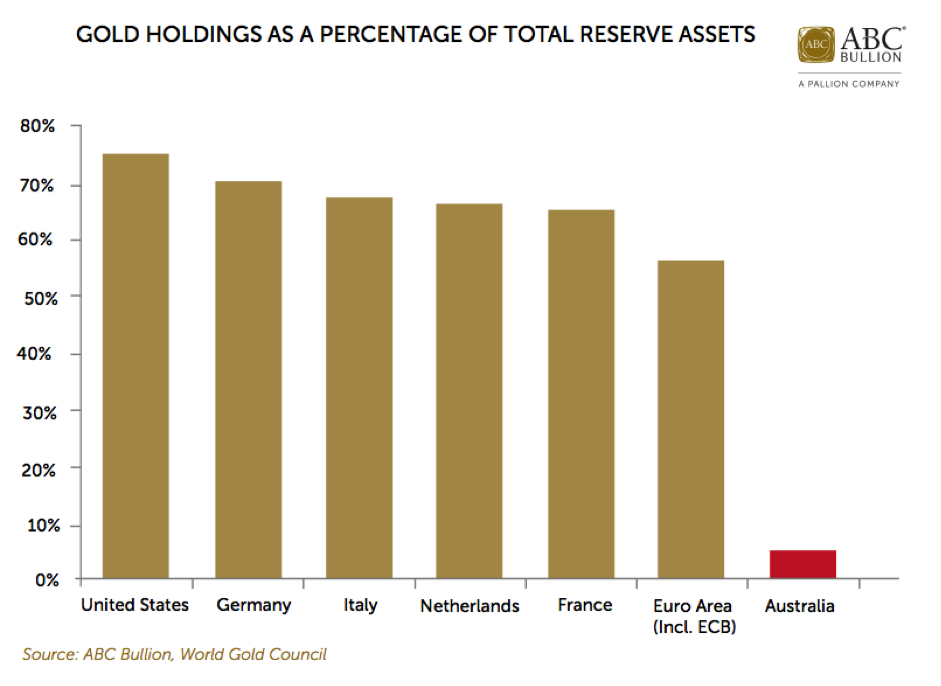

RBA gold holdings currently make up less than 5% of our foreign reserve assets, a number that is alarmingly low when compared to the holdings of other developed market nations, as you can see in the following chart.

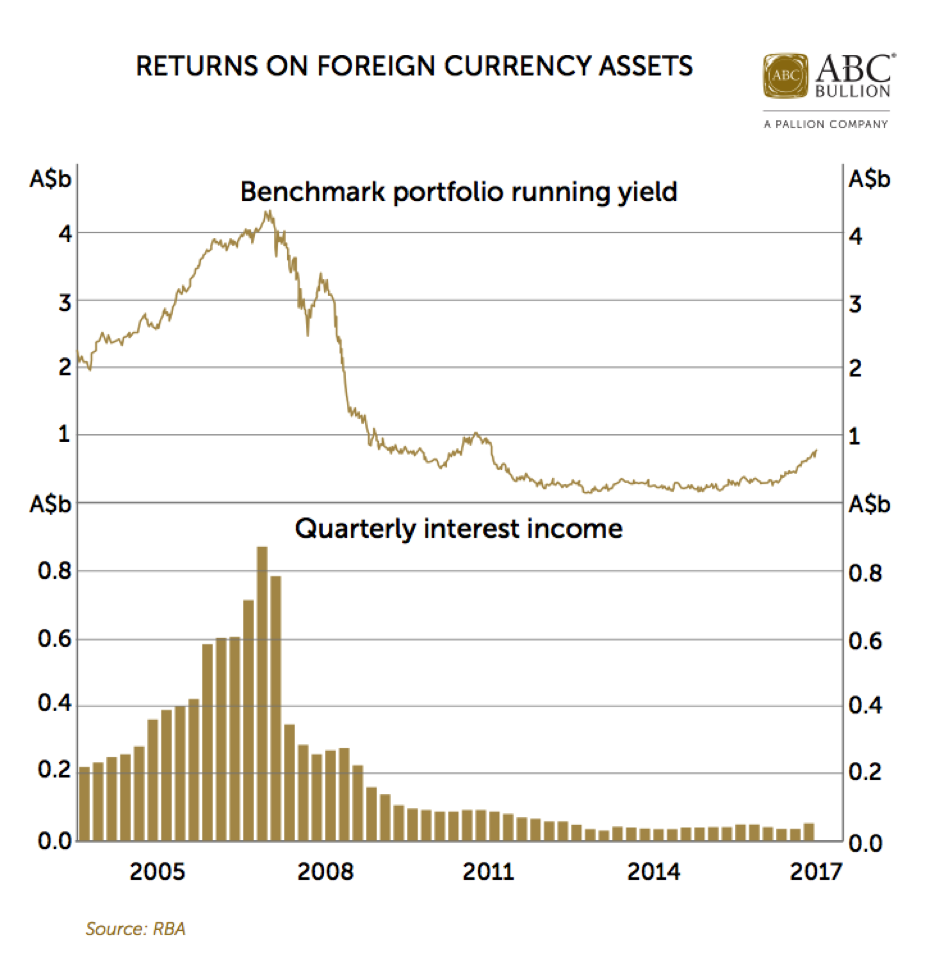

Adding further weight to the argument that our national gold reserve needs to be rebuilt is the lack of income being generated on our portfolio of foreign exchange assets, which is a function of the record low yield environment that central banks the world over have created in the post GFC environment.

The latest RBA annual includes the following chart, which highlights the fact we earn less than 1% on our assets, and how far returns have fallen since GFC hit.

Given the RBA actually earns roughly 0.20% on its gold loans (contrary to popular opinion, one can earn a yield on gold), there is little opportunity cost in terms of the income we’d likely forego should we rebuild our gold reserves.

We for one can certainly understand why a central bank (or any investor for that matter) might look to trim their gold holdings if they could earn close to 4% or 5% in ‘real’ terms investing in low risk, low volatility financial assets, but we are not operating in that kind of environment today, and likely won’t be for years to come.

The deterioration in public sector balance sheets (see table below) across the developed world adds weight to this argument, as the end result will almost certainly be higher inflation in the coming years

Given this backdrop, the RBA would benefit by topping up our physical gold reserves.

Central Bank Gold Buying – a Global Trend!

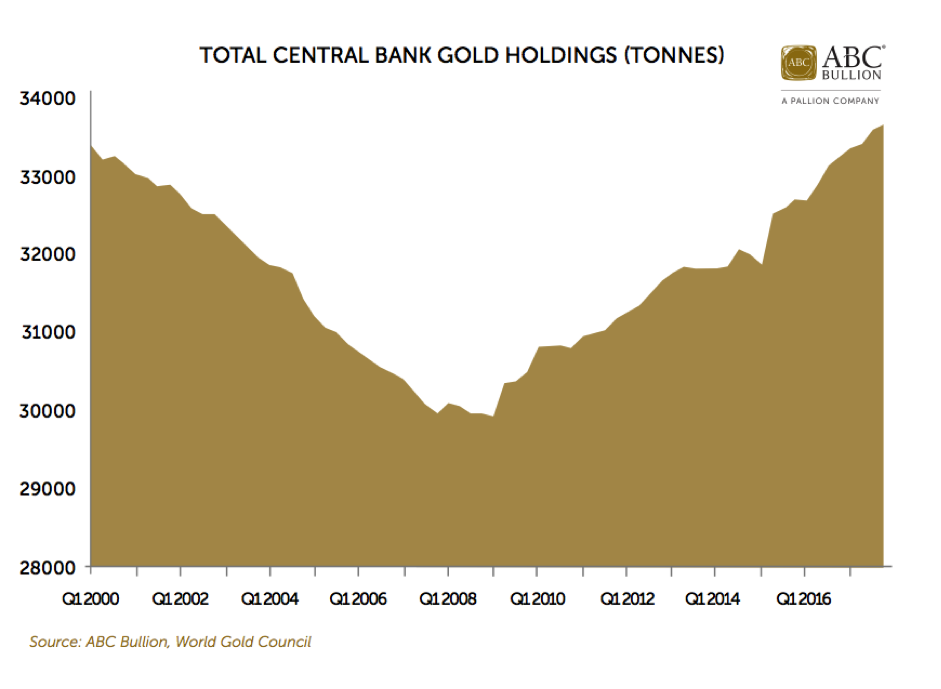

Since the GFC hit, central banks have turned net buyers of physical gold. Collectively, they’ve purchased the better part of 3,000 tonnes of gold in the past 8 years with total official gold reserves now back to where they were in 1999, as you can see in the chart below.

The buying has been spearheaded by emerging market nations, including China, India, Russia, Kazakhstan and Turkey, many of which are likely to be accumulating for some time too, as on average, they still have less than 8% of their reserves in gold, a number far below that of the United States, and many European nations.

Gold Repatriation!

Since the GFC hit, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, and most importantly, the Germans, have all either moved, or are taking steps to move some of their gold holdings within their own borders.

The only logical conclusion one can draw from observing this activity is that central banks are in no doubt as to the importance of holding this unique monetary asset.

The RBA should take note

Summary

Given the paucity of yield on offer in sovereign bonds, the historical inevitability of higher inflation, and its unique attributes as a monetary asset, now is the time for the RBA to begin increasing our gold reserve.

A 15-20% weighting would be appropriate, in line with our holdings prior to the 1997 gold sale, and roughly equivalent to the proportion of foreign reserve assets that gold constituted when the ECB was formed back in the late 1990s.

Crucially, we believe a significant portion of these reserves should be held within Australia.

After all, Australia is a politically stable, AAA rated sovereign. Given this, there seems little point in mining and refining physical gold in Australia, only to have all of our national gold reserves held offshore.

Storing national gold reserves locally would also send a positive message to Asia, where gold is very much seen as money by both citizens and central banks alike. Indeed, provided it was leveraged the right way by the private sector, a decision to rebuild our national gold reserves could help open up avenues to grow our banking and financial services links with the region.

Most importantly, rebuilding our national physical gold reserve will better balance out the RBA’s reserve assets, and help to hold the good ship Australia in good stead through what may well be some rough years ahead.

Full report here.

4 topics

.jpg)

.jpg)