Miners Regain Their Appetite

The mining industry collectively had to address a range of issues to ensure survival between circa 2011 and 2015. Having met the top of the market with bloated balance sheets and unsustainable costs, austerity was rolled out. But unlike many mining initiatives there were no commemorative shirts or hats. The collective attitude toward growth was put into reverse as dividends were cut, capital was raised and high cost or short life assets were sold or closed as the world’s miners were suffering severe indigestion – of expensive, top of the market acquisitions and funding themselves with too much debt. Exploration and business development (read: anything that leads up to potential M&A) activities were shut down.

Given time to digest, and develop a new wellness regime, the sector’s financial health has certainly improved dramatically since 2011. Debt levels have been reduced, dividends are back and even improving, and discipline around expenditure is a buzz phrase. Over the last three years, as financial health has been regained, exploration and investigation of future potential production has become more vigorous. Very recently we have seen two very large merger deals that smack of “big wanting to be bigger”, which were both bold growth steps and mark a step change in deal making character for miners.

Exploring Again

Exploration is an essential function – mining is unique as an industry, having to regularly invest to identify future sources of production. Notwithstanding, exploration is expended when budgets are tight. Exploration activity across the industry declined from 2011 to 2015, but (using ABS figures as a proxy) exploration activity (expenditure and / or meters drilled) increased in 2016, 2017 and 2018. Exploration activity is one of the first signals that a sustainable recovery of funding has occurred – the industry is very clearly investing in its future again, and this is with the tacit approval of the market.

Over the last 10-20 years, two trends in exploration have emerged with important consequences for future mining development:

- Discovery rate has been declining. This is especially apparent in major metal markets like gold and base metals, peak years of discoveries were decades ago and success in ensuing years have been progressively becoming slimmer

- The companies that account for the greatest, and growing proportion of discoveries are juniors – not the major companies who have the greatest need to replace production. Juniors are also the least well-funded strata within the sector – so there is a logical transmission of ownership from finder to developer or long-term operator that is likely to take place over time

Merger’s and Acquisitions – OK Again

If there was a nomination for the most detested phrase in mining, “mergers and acquisitions” would have rated very highly, from circa 2011 up until quite recently. Many investors still remember hostile, premium priced and very expensive deals from the last boom when a major miner “had to have” a smaller suitor. Many miners probably recall these deals too, with a twinkle in their eye – much like reminiscences of teenage escapades which succeeded because no one of any authority was watching – although would all probably profess to a great deal more maturity now.

There were nominations for “worst deal” over the last decade, and there were plenty to choose from ! No need to pick that scab off again now though – suffice to say, like an over-indulgent diner, large miners have only really returned to vigorous activity “gingerly”. The major miners took the Zantac administered by their investors, and had a lay down. The character of M&A activity by major miners, has been small denomination and dominated by investments into joint ventures or equity of junior companies. This has a strong whiff of future takeovers about it, but is long dated and subject to technical success along the way. So whilst presently unthreatening, this behaviour has seen a healthy vertical connection between large and small companies to facilitate project progression.

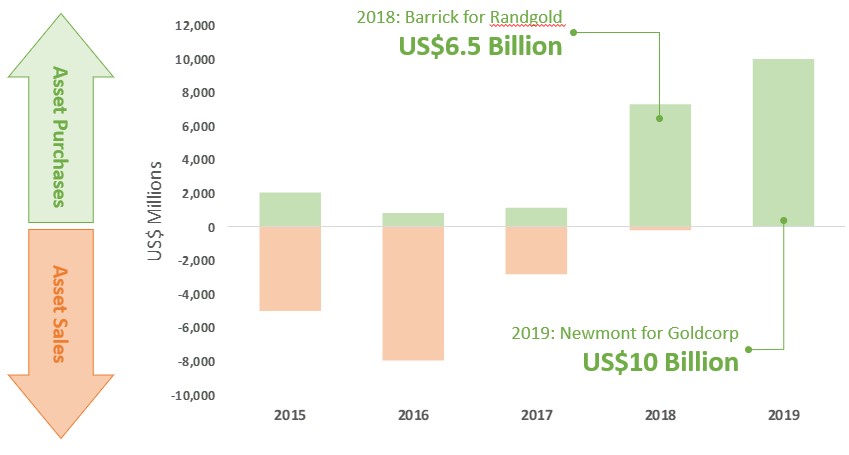

Suddenly, in late 2018, a new character of deals re-emerged after a long while of absence. In September 2018 Barrick and Randgold announced a merger which saw Barrick acquire Randgold for US$6.5B in a nil premium paper deal. Perhaps the key executives fist pumped and mouthed “BOOM”, but the market reaction was virtually indifferent. This reaction tells us two things: first, there was no market disapproval; and second, the market hasn’t gone on to re-value other potential targets. The market was saying “these sort of deals are now OK, but we don’t see many more on the horizon”. Shortly after, in January 2019, Newmont announced a US$10B acquisition of Goldcorp – also a paper deal, this time with a modest premium (the premium shrinks for longer VWAP’s). If this deal is consummated, it will have been the largest gold acquisition ever, to create the worlds largest gold company – there are some serious size connotations bandied about here !

One swallow may not make a summer, but one enormous gold deal followed by an even larger one certainly suggests more than one team have been thinking along very similar lines. These two deals have reversed the trend of deals in the gold sector, and whilst that isn’t necessarily indicative of the rest of the industry, all of a sudden it certainly seems as if the big want to get bigger again – and the market approves.

Time ticks on

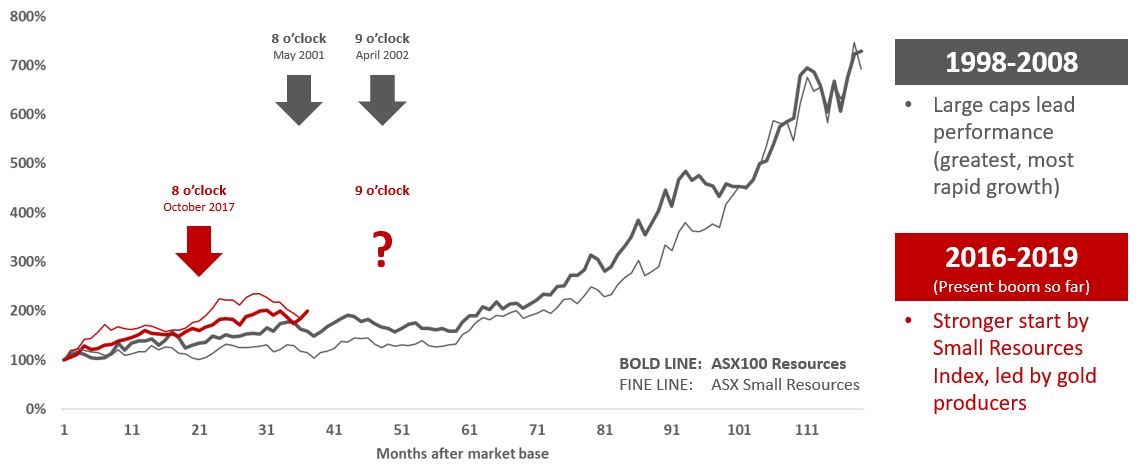

The reinvigoration of exploration, and investments by majors into juniors clearly demonstrate that interest in strategic growth has returned, even if these actions have a reasonably long fuse. The emergence of large-scale M&A in the gold sector in late 2018 is a crucial advancement of mining deal making and indicates that scale has again become important. These deals are far from top-of-the-market in character – both were low / nil premium and non-hostile. There is a fair way to go yet for deal making appetite to spread across the sector and become competitive. The Lion Mining Clock is moving forward, and although it’s not nine o’clock yet, has ticked just passed eight.

But, But, BUT !

“BUT WAIT” I hear all the managing directors of junior miners cry in unison – “what about us ?”. Very little of the enthusiasm that the market has shown to operating miners (especially for the large caps) has trickled down into the juniors yet. Of the 44 metals and mining companies in the ASX100 Resources and Small Resources Indices, 41 of them have made a positive share price performance since 1 January 2016 and the median performance of the respective groups is +137% and +164% respectively. In very stark contrast, the 533 metals and mining companies that fall below those indices have a median performance of -11%, and almost 2/3 of that population are trading at a lower share price than they started 2016.

If all miners lived in the same pond, the larger companies would be in the middle, and feel all the splashes and ripples of a rock being thrown into the water. Juniors would be at the edges, and have to wait for the ripples to dissipate out to the edges which can be slow and frustrating. But there is hope – All mining cycles eventually feature a growing amount of money looking down the market capitalisation scale, so history assures us this will take place in time.

Reflecting on previous cycles, 8 o’clock was during 2001 and 9 o’clock during 2002. Macarthur Coal and Sally Malay (now Panoramic) were listed in 2001; Independence, Avoca and Westonia (now Evolution) were listed in 2002. Large miners were dealing: Rio Tinto successfully bid for North and Ashton, BHP took Billiton and Barrick took Homestake – the industry was certainly investing. Then, much like now, fund raising and share price performance in the market for juniors was tough. That cycle lasted another six years after the eight to nine o’clock phase.

1 topic