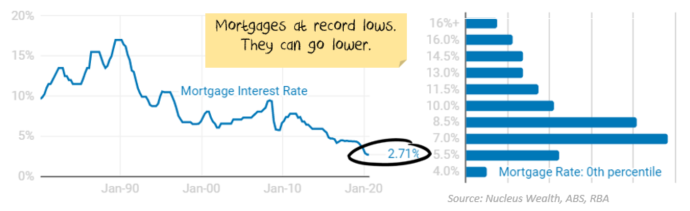

Mortgage rates can (and will) go much lower

Before COVID-19 hit, Nucleus Wealth launched an Australian property calculator. The idea I wanted to illustrate is that house prices are very sensitive to interest rates. So, with interest rates so low, property was going to be stuck in purgatory:

- if the economy improved and interest rates increased then higher interest rates would cap property prices,

- if the economy didn’t improve, then weak growth and already low interest rates would see property prices fall

I’ve changed my mind. Desperate times call for desperate measures. I’m pretty sure mortgage interest rates are going lower. Much, much lower.

A mistake in our property calculator

In our house price calculator, we had a minimum mortgage rate setting of 2%. It should have been much lower. We just changed it to 0.5%.

Impossible? Japan has mortgage interest rates below that. So does Germany. Ditto France. And there is a decent probability the rest of the developed world is destined for the same.

It is already happening

The mechanism is already set up in Australia. The Reserve Bank of Australia has begun providing three-year funding to banks at 0.25% for mortgages. Banks can probably use this money to go below 2% for three-year loans. And that is just the beginning.

It started in April with an “initial” funding allowance for banks. Then an “additional” funding allowance. Now there is a “supplementary” one.

There is clearly a risk of running out of adjectives to describe the bank funding. But there is no risk of running out of the desire to keep the property market ticking over with low interest rates and oodles of credit. The Treasurer’s announcement last week requesting banks to start lending irresponsibly confirmed that for anyone who still doubted.

Europe has already paved the way. The European Central Bank started with 0.1% funding for banks in 2014. By 2016 the rate was -0.4%. Now, -1.0%. Yes, the central bank will pay commercial banks up to 1% if they can just find someone (anyone!!!) who will just borrow the money.

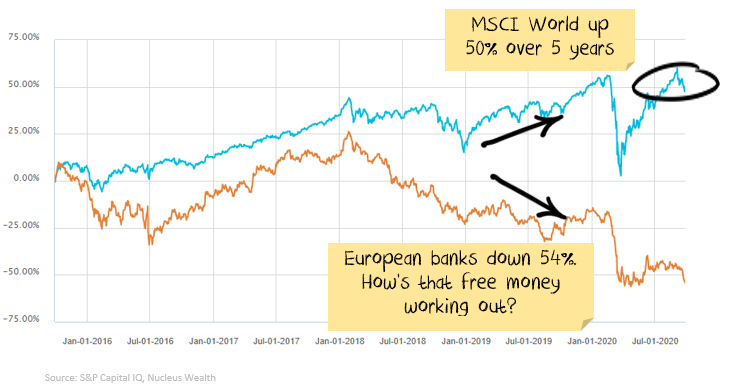

Wow – great news for bank investors, being paid to make loans!

Nope. It is the flat yield curve problem smashing bank profitability, I’ve posted about it several times.

Don’t think of it as free money for banks. Think of it as life support so that the banking industry doesn’t collapse.

What does this do to residential property forecasting?

Keep in mind that I’m talking about forecasting residential property in aggregate – not individual houses or suburbs.

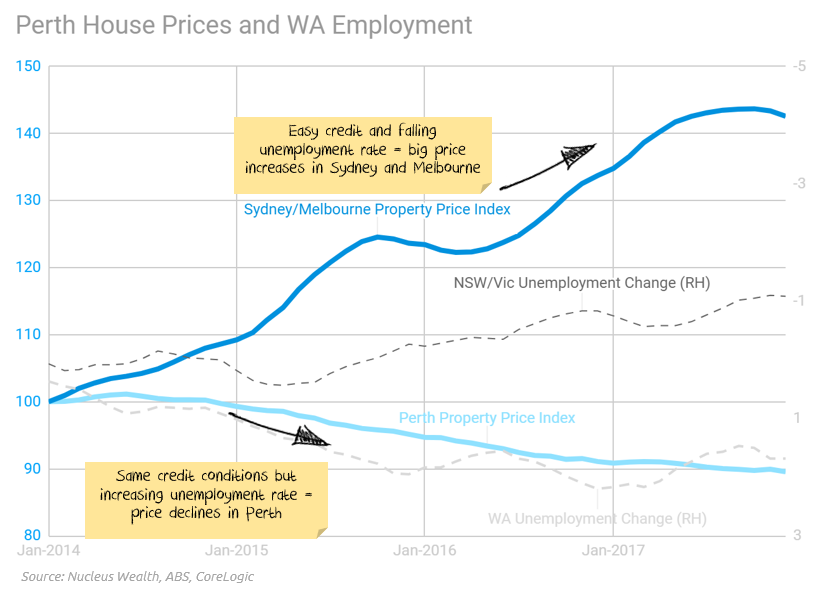

There are significant links between property prices and the availability of debt. The financial crisis showed this internationally. The Royal Commission into banking showed this in Australia. When the amount of debt available rises, so do property values. When debt slows down, property values fall.

The Federal Government is hellbent on forcing more debt onto borrowers. The Reserve Bank of Australia is providing the funding. Credit is available.

I’m going to argue four other factors also constrain how high or low property prices can go. These are the four factors you can use to forecast property prices in our online calculator:

- Mortgage Payments to Rent: comparing the cost of a mortgage with the cost of renting the same house. By using this ratio to constrain house prices, we assume when the ratio gets high that people will prefer to rent rather than buy.

- Mortgage Payments to Wages: assuming when the ratio gets high, people rent because they cannot afford to buy.

- Property Prices to Wages: assuming when the ratio gets high, people rent because they cannot save enough money to afford a deposit. We treat this as less important than the above two ratios.

- Rental Yield: Rental yield is the annual rent divided by the property price. By using this ratio to forecast prices, you are assuming when the ratio gets low investors will not buy property as they are not getting a return that is high enough.

Australia can be #1 in the household debt race

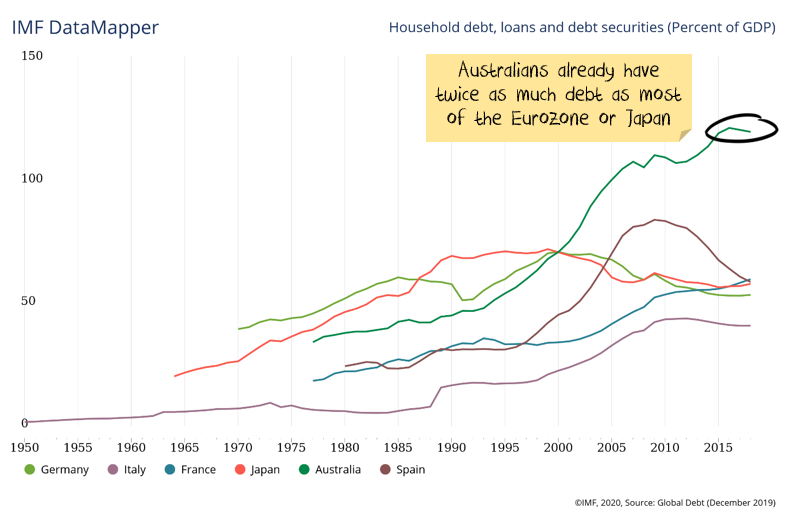

Strap yourself in for moral hazard. We already have the world’s 2nd highest consumer debt, about double most Eurozone countries. If interest rates can fall further and the shackles are off the banks for responsible lending, then who knows how much more indebted we can become?

Investment Outlook

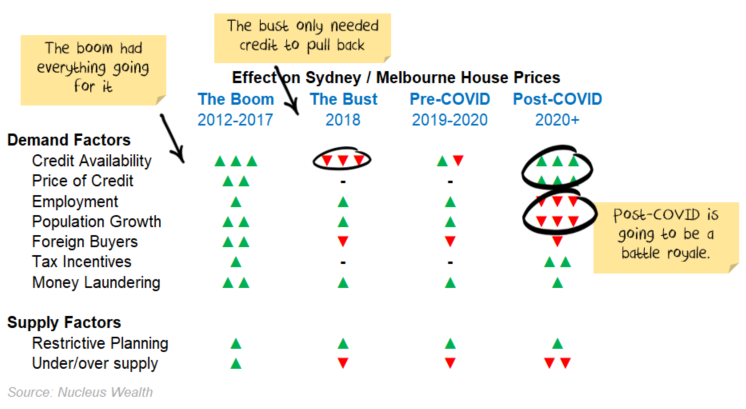

It is a fascinating showdown.

On the one hand, we have plummeting immigration, massive unemployment, eviction moratoriums to deal with, bankruptcies to deal with and a larger private debt burden that just about any other country.

On the other, we have a burning political desire to keep house prices high, pump more debt into the economy and a roadmap to much lower interest rates to help.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Appendix: Australian property calculator valuation summary

The net effect (see individual city data below for more info) is:

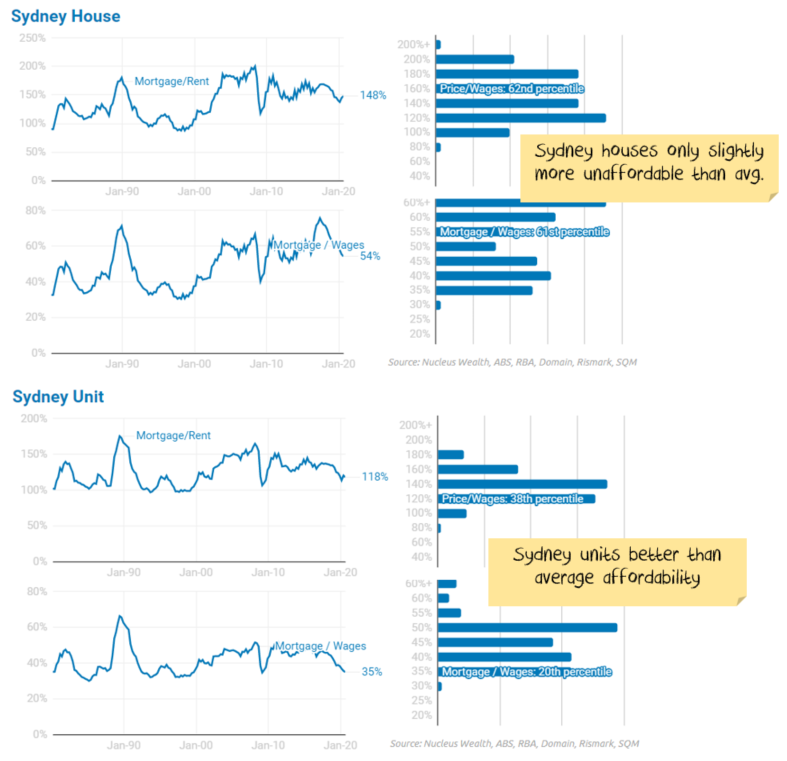

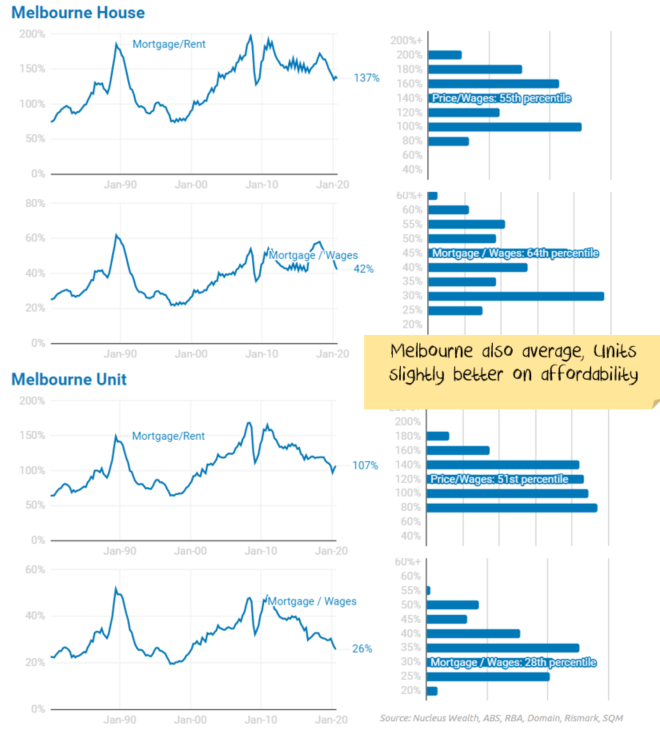

- The cost of a mortgage relative to the cost of rent is about average in Sydney and Melbourne. In Brisbane and Perth, the cost of a mortgage is cheap relative to the cost of rent. Both rents and mortgage costs are likely to continue to fall, but mortgage costs can fall further, improving affordability.

- The cost of a mortgage relative to wages is about average in Sydney and Melbourne. It is cheap in other cities. The problem is two-fold: (a) wage growth is not going to be high (b) unemployment is high. A positive longer term sign for house prices, a negative shorter term sign.

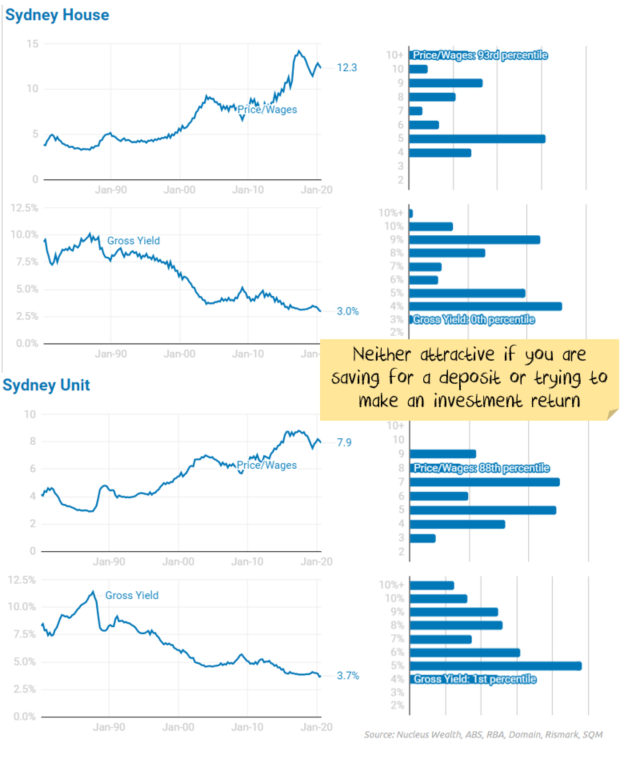

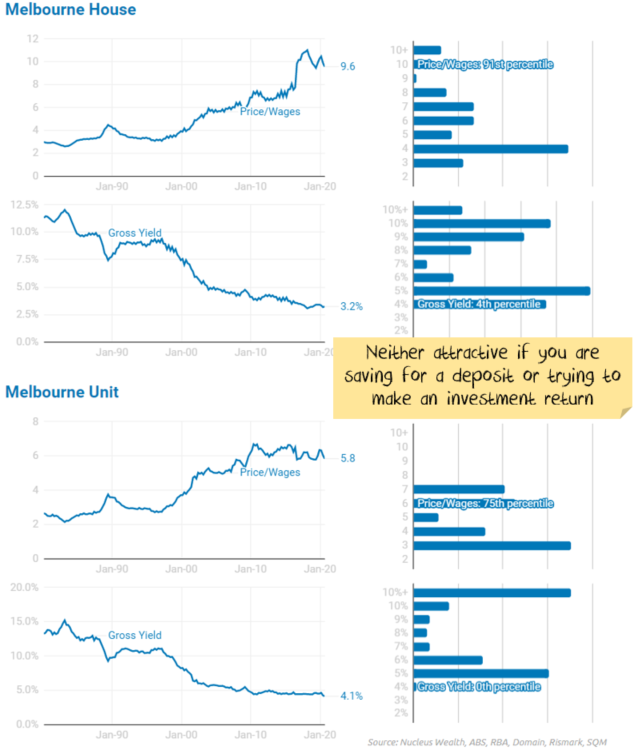

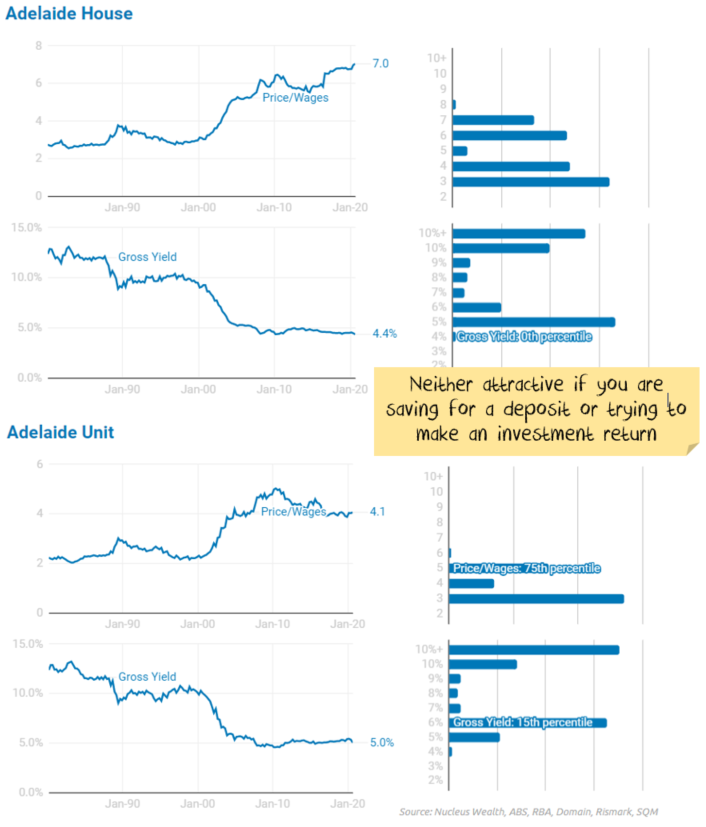

- House price to wages are close to historical highs in every city except Perth.

- Rental yields are close to historical lows in every city except Perth. Eviction moratoriums and rental declines are not helping investors.

City valuation detail

Sydney

The chart on the left shows how each of the ratios used for forecasting in the property calculator have changed over 40 years. The histogram on the right shows the distribution of the same ratio over the 40 years.

Melbourne

The chart on the left shows how each of the ratios used for forecasting in the property calculator have changed over 40 years. The histogram on the right shows the distribution of the same ratio over the 40 years.

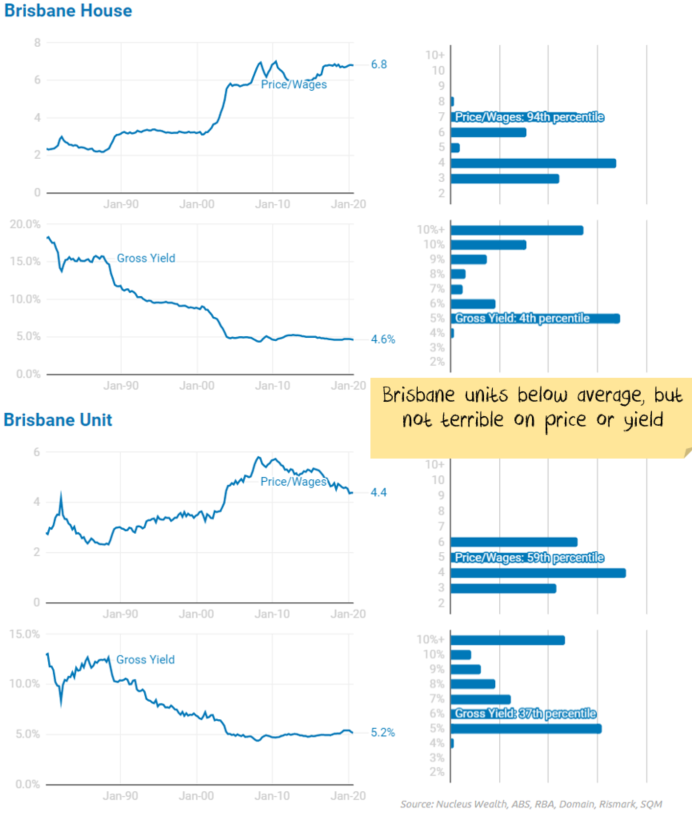

Brisbane

The chart on the left shows how each of the ratios used for forecasting in the property calculator have changed over 40 years. The histogram on the right shows the distribution of the same ratio over the 40 years.

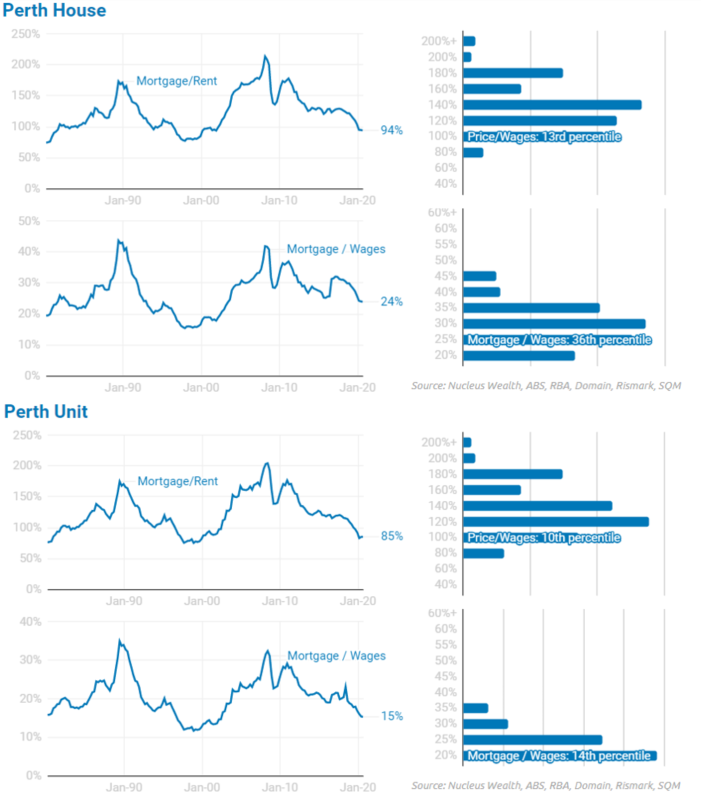

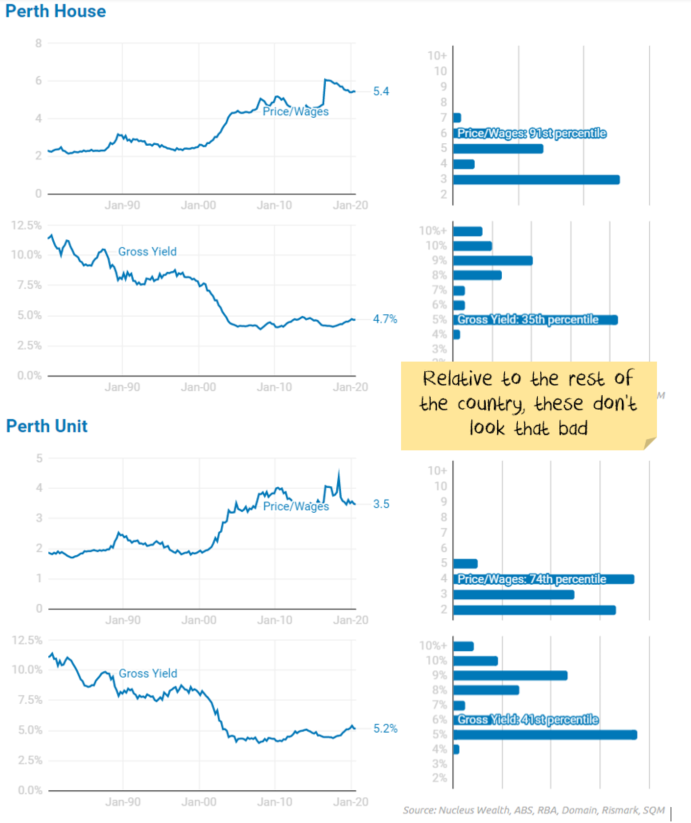

Perth

The chart on the left shows how each of the ratios used for forecasting in the property calculator have changed over 40 years. The histogram on the right shows the distribution of the same ratio over the 40 years.

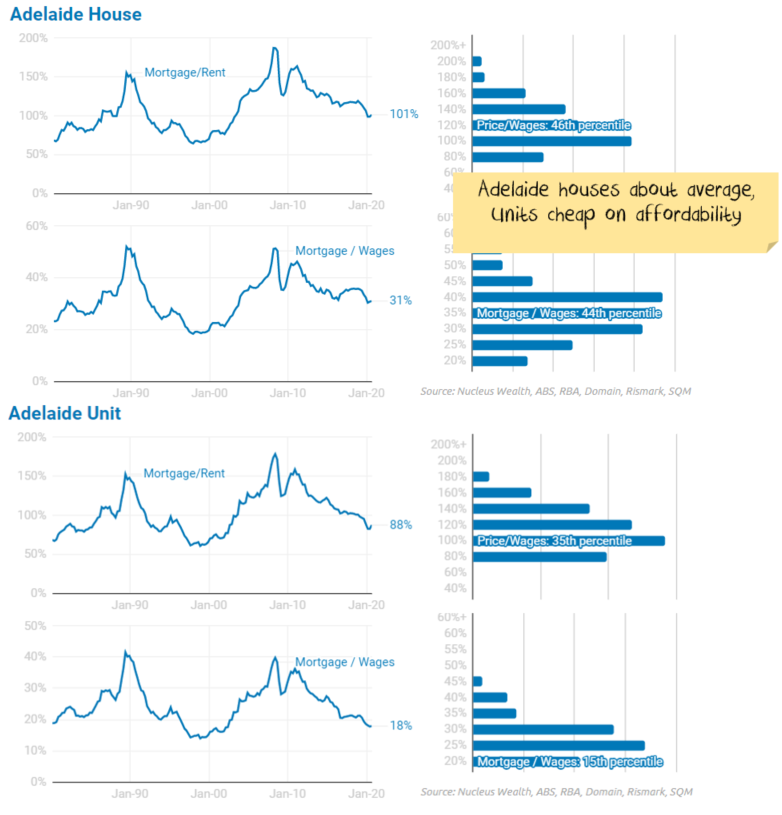

Adelaide

The chart on the left shows how each of the ratios used for forecasting in the property calculator have changed over 40 years. The histogram on the right shows the distribution of the same ratio over the 40 years.

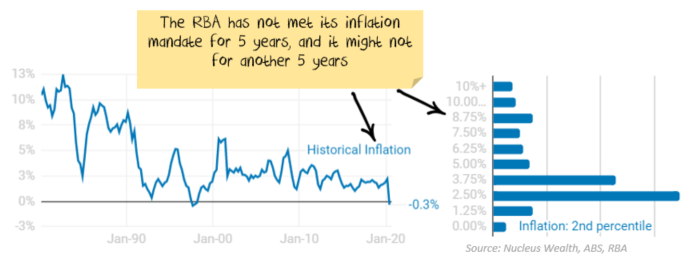

Macroeconomic factors:

Inflation

Employment

Mortgage rates

Sources:

Nucleus Wealth has compiled this data using a range of different sources.

For property prices and rents we use a Domain for more recent data quarterly data, cross checked with SQM and Rismark to fill any short term moves. For older data we use Australian Bureau of Statistics data to fill timeseries.

For economic data we use either Reserve Bank of Australia or Australia Bureau of Statistics data. For older data we have had to estimate some factors due to differing definitions over time.

More information on forecasting factors:

Mortgage cost to rent

This is a comparison of the cost of a mortgage with a 20% deposit, compared to the cost of renting the same house. By using this ratio to constrain house prices, we assume when the ratio gets high that people will prefer to rent rather than buy.

The consequence will be either (1) property prices will fall until it becomes more attractive for people to buy or (2) the Reserve Bank will lower interest rates and so the cost of a mortgage will decrease.

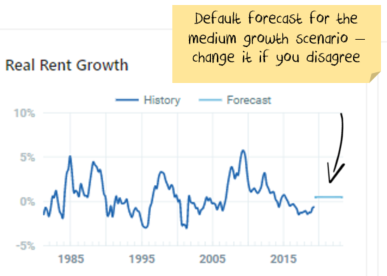

The benefit of using this ratio is it provides insight into the decisions both homeowners and investors are making. When the cost of a mortgage is cheaper than renting for a homeowner, or an investor can see their mortgage paid for by the rent, then prices tend up. Also, rent is a relatively stable series:

i.e. rents tend to go up a little more or a little less than inflation

The problem with using this series is that you can get significant changes in the series as central banks raise interest rates to slow the economy and then cut them to stimulate. It also ignores wage growth – strong wage growth supports higher prices. It ignores the higher deposits needed with higher house prices.

Mortgage cost to wages

By using this ratio to constrain prices, you are assuming when the ratio gets high, people rent because they cannot afford to buy. The consequence will be either (1) property prices will fall until it becomes affordable for people to purchase or (2) wages will rise until it becomes affordable for people to buy.

The benefit of using this ratio is that it provides a realistic impression of the decision many homeowners make: they spend as much as they can afford. Also, wages are even more stable than rents:

i.e. wages tend to go up a little more than inflation each year without much variation.

The problem with using this series is the same as the above: you can get significant changes in the series as central banks raise interest rates to slow the economy and then cut them to stimulate.

Property Price to wages

By using this ratio to forecast prices, you are assuming when the ratio gets high people rent because they cannot save enough money to afford a deposit. The consequence will be either (1) property prices will fall until it becomes more affordable for people to buy or (2) wages will rise until it becomes affordable for people to buy.

The benefit of using this ratio is that it provides an additional dimension to the 2nd factor. Homeowners spend as much as they can afford, but they need to be able to save the deposit. This helps to indicate whether they can.

The problem with using this series is that it doesn’t incorporate falling interest rates or changes in rent. For this reason, I tend not to use this as my primary forecasting method, more of an additional check on the outcomes.

Rental Yield

Rental yield is the annual rent divided by the property price. By using this ratio to forecast prices, you are assuming when the ratio gets low investors will not buy property as they are not getting a return that is high enough. The consequence will be either (1) house prices will fall until it becomes more attractive for investors to buy or (2) rents will rise until it becomes attractive for investors to buy.

The benefit of using this ratio is that it provides a better indication of investor returns.

The problem with using this series is that it is hard to forecast. There is (probably?) a limit to how low yields can go, especially as there are only a few more rate cuts left. I would argue that the net (i.e. after subtracting costs) yield is a better indicator, but this is much harder to observe and requires guesswork. Another alternative would be the yield relative to something like a ten-year government bond. This would show the return for investors relative to other opportunities. However, if you wanted to forecast property prices that way, your first step would need to be to predict the 10-year bond rate, which is making forecasting harder rather than easier. For these reasons, I tend not to use this as my main forecasting method, more of a supplementary check on the outcomes.

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

5 topics