Net-zero by 2050 is unlikely: So here's how you should invest

There are very few people that I would be happy to spend my Thursday evening speaking to late into the night. But, abrdn's Jeremy Lawson happens to be one of them.

As the investment manager's chief economist and head of the abrdn Research Institute, Lawson has a very interesting story to tell (and isn't one to beat around the bush either). He grew up in outer suburban Adelaide but always wanted to explore the rest of the world. Unsurprisingly then, his career has been filled with an array of roles that have allowed him to focus his life and career on experiencing things that many wouldn't.

Who else has served as the climate policy advisor to Kevin Rudd in the run-up to the 2007 federal election, while working as a senior economist at the Reserve Bank of Australia? Then jetted off to Paris to work for the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (the OECD)?

That's before working in Washington and New York with the Institute of International Finance and BNP Paribas. And ultimately, nabbing a role with abrdn in the UK in 2013, where he has lived and worked for the past nine years.

And while Lawson is positive on a number of things, the world getting to net-zero by 2050 isn't one of them (and the war in Ukraine hasn't changed the status quo).

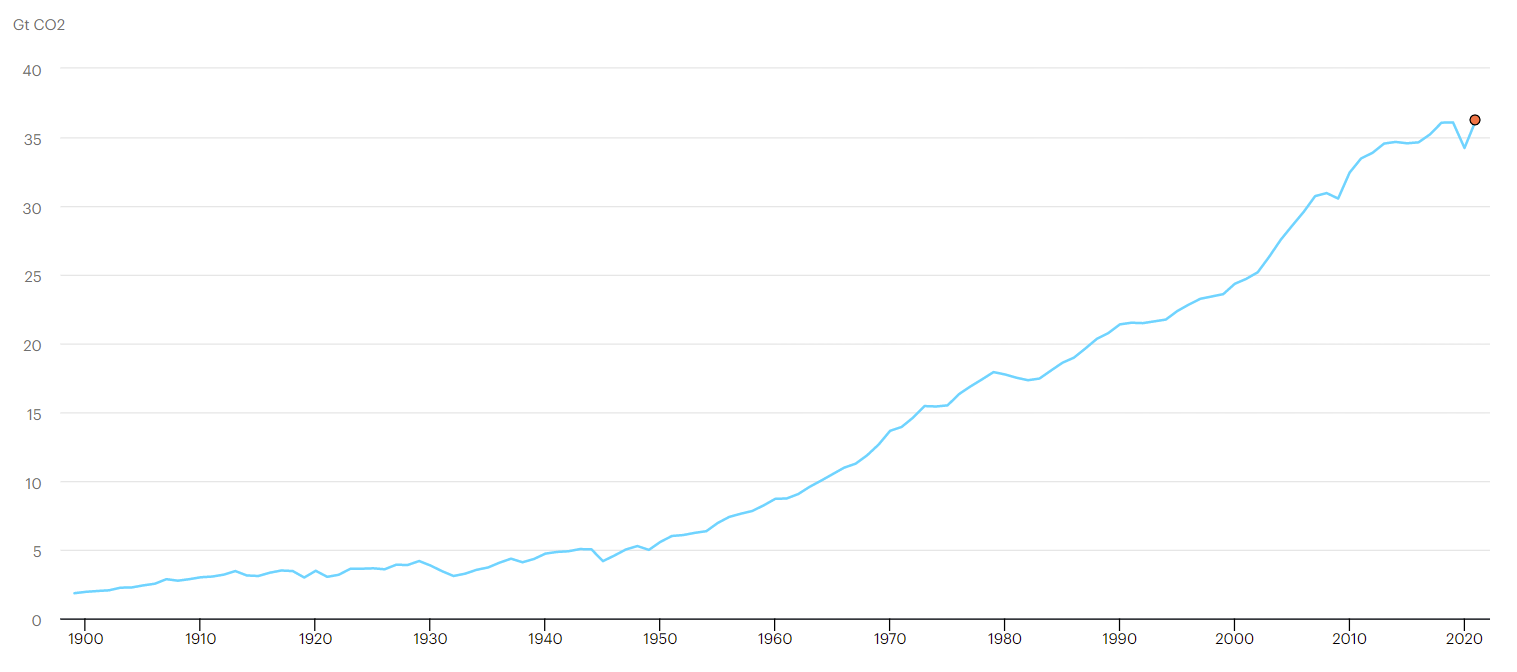

"The reality is that net-zero alignment requires global emissions to decline by about 7% per annum on average every year, over a 30-year period," he says.

"Even at the peak of the global shutdowns during the pandemic, global emissions didn't even fall by that amount. And so it's a good way of thinking about just how drastic and rapid changes need to be to have net-zero alignment."

CO2 emissions from energy combustion and industrial processes, 1900-2021

The issue, according to Lawson, is that there are very few countries and regions that actually have policies and regulation in place to drive a shift to decarbonisation at that level.

"The reality on the ground is that few of the largest emitting companies or countries, none of the really important decision-makers that could make net-zero by 2050 possible are really treating it as though it is a truly serious target," he explains.

"And so in the financial industry, it becomes a phrase that's sometimes thrown around too easily. As though it's something that is likely to happen. And the reality is there's been a gap opening up for a long period of time. Even the scientists are beginning to lose hope."

That's not to say we should just give up. Even if 1.5°C becomes unattainable, Lawson believes that we should aim for the smallest temperature increase we possibly can.

"What we would need to do is try to generate negative emissions in the future on a large enough scale so that we could bring temperatures down rather than just stabilise them at a particular level," he adds.

In this profile, you'll learn how Lawson believes you should invest as this gap continues to widen. He also outlines what he believes needs to change in Australia for our country to become a renewable energy leader, as well as the biggest risk to markets right now.

Note: This interview took place on the 21st of April 2022.

The one thing markets don't understand about decarbonisation and climate change

It is much more difficult for governments to put policies in place to support the energy transition at the speed and scale that is required than investors sometimes think, Lawson says.

"Many people in the market have a weak understanding of the political drivers of policy change. And because they have that weak understanding, they don't have a good lens with which to think about what is probable," he says.

"That can then lead them to make decisions that don't factor that in - how that's going to influence the potential return of a particular investment. I see it all the time."

Investors cannot assume that the world is going to hit the net-zero target (and invest on that basis), he adds.

"Investors may remember 'Abenomics'," Lawson says.

"Former prime minister Abe came to power 10 years ago in Japan and promised a massive structural reform agenda. Investors clamoured to get access to Japanese equities on the basis that this reform was going to transform economic growth in Japan."

The problem is, it didn't.

"These opportunities turned out to be nowhere near as large or as persistent as some people had hoped. And climate change and climate policy are very similar," Lawson explains.

"Hundreds of different regulations and policies have to be put in place to generate a consistent, significant, rapid transition. And I think people get bored of that type of detail. They don't understand the barriers and how they differ across countries, across sectors.

"And so they sometimes invest at the wrong time, buying high or selling low. And so something that should be a driver of performance doesn't end up being one."

Perhaps naively, I ask whether companies can implement change without robust governmental policy. And while Lawson says they can certainly complement it, he admits they can't drive change on their own.

"Climate change itself is a market failure. If I'm an electricity generating company and I've got coal in my portfolio, who bears the costs when I produce emissions from burning coal? Is it me or is it the planet?" He says.

"Those costs go everywhere. I don't bear the sole responsibility for them. They don't reflect only on my own bottom line. And because of that, you'll always get a gap between what's socially environmentally the best outcome, and how private companies are incentivised to act."

This gap, this wedge, will continue to exist until government policy forces companies to consider the broader consequences of their actions.

"There's no way around it," Lawson says.

"It's not to say that companies shouldn't be looking to the future and finding ways to decarbonise. And there are lots of business opportunities for doing so, but collectively they won't be able to get to net-zero aligned outcomes unless they're being forced by government change."

Don't Look Up

If you are reading this and getting serious "Don't Look Up" flashbacks, you're not alone. The 2021 Netflix blockbuster follows two astronomers hell-bent on warning the world of an approaching comet that will destroy the planet - a not so subtle analogy for the world's tepid approach to dealing with global disasters, or ahem... climate change.

"The political environment has become very fragmented and polarised over the last 10 to 15 years in a lot of countries. And increasingly, we talk with people in our own echo chambers," Lawson says.

"I've worked in the Labor Party. And a lot of the people I know have come from that side of politics. And it's the easiest thing in the world to just talk to people who agree with you."

For those who haven't seen it, in the film, the characters who don't agree with the central premise of the movie, that a comet is going to destroy Earth, are not taken seriously and are portrayed in a cartoonish if not humorous manner.

"If the film is a parable for climate change, the danger of that is you are not going to generate stronger climate policy if you treat every person who currently disagrees with that, for whatever reason, as though they are fools," Lawson says.

"Take Australia. Australia has large communities who are partially or significantly dependent on fossil fuels. If you can't bring them along for the ride, if you can't say that there's an economic future for your community in a world that's transitioning away from fossil fuels, then they're never going to sign on for that."

In this way, we don't want to fall into the trope of portraying everybody who disagrees with the move to net-zero as the enemy, he says.

"If we do, then we'll just continue to be wired to this sclerosis that we've been in for the last 15 years of climate policy in Australia," Lawson says.

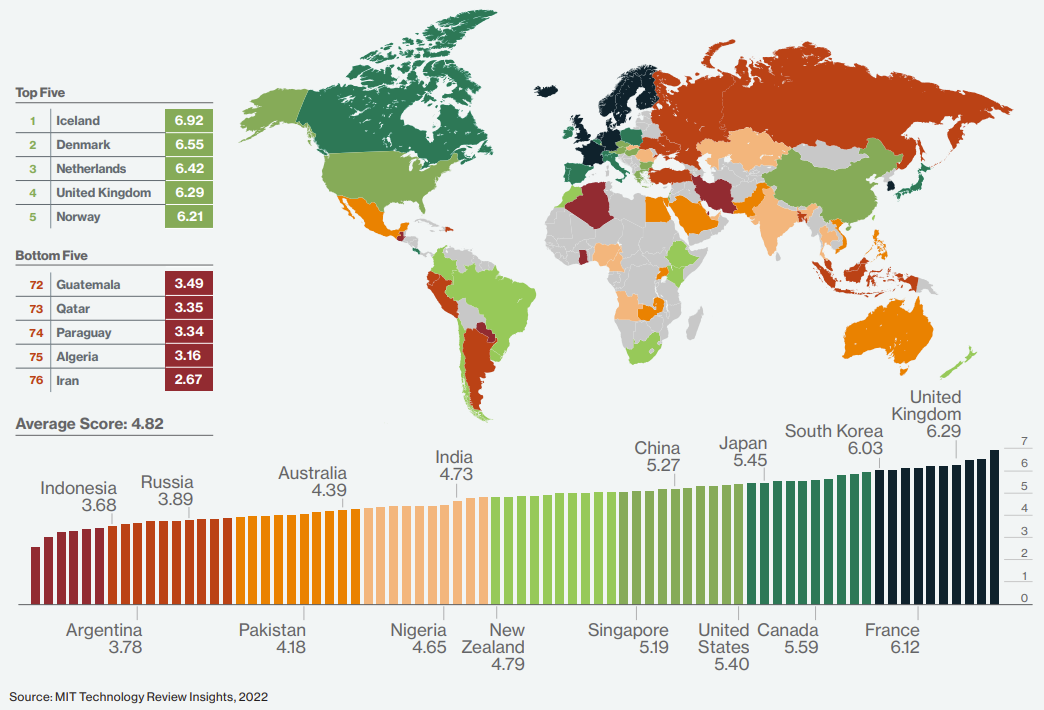

Currently, Australia is ranked pretty poorly when it comes to our readiness for a green transition.

The Green Future Index 2022 rankings world map

"It's not only embarrassing, but Australia has some of the greatest renewable potential in the world. There is an enormous opportunity here, but we are trapped between our economic past and our economic future," Lawson says.

"We're too frightened to embrace that change, in part because short-term political considerations seem to dominate everything else. And so we've lagged many other parts of the world."

So how do you invest in this "enormous opportunity"?

You don't need to be a genius to recognise that there's been some recent tension between short and long-term drivers of markets. Commodity prices, for example, have shot the lights out, and carbon-intensive businesses, like oil and gas companies, have seen their margins increase significantly. The strong drivers that were already in place before Russia invaded Ukraine have then been amplified by the war itself.

"Many of these companies have actually quite bleak long-term futures - not all of them - but if they don't have credible transition plans, then they're going to struggle," Lawson says.

"But in the short term, that isn't true."

This "short-termism" makes it difficult to invest in "green" companies as money managers have track records to adhere to, he notes. After all, how many clients are willing to forego returns now in the hope of greater returns in the future from cleaner investments?

Also adding fuel to carbon-intensive companies' fire is the small number (or lack thereof) of pure-play "green" companies in the S&P/ASX 200, Lawson adds.

"You either need to expand your investment universe or ultimately focus on what they call "transition" companies - companies that are currently 'brown' but have some prospect of becoming 'green' over time," he says.

Unfortunately, identifying credible transition firms is not as straightforward as one may hope.

"You have to look very deeply underneath the hood of the claims that these companies make," Lawson says.

"For example, and without naming names, it could turn out that actually, this company is incredibly reliant on carbon capture and storage being viable. Or they're pledging to plant a forest the size of Brazil - things that are just very, very unlikely to occur. Or they might say they will be net-zero by 2050, but actually, they're not planning on decarbonizing for the next 10 years."

Therefore, investors need to identify those companies that actually have a good probability of transitioning from those that don't.

"It's a bit like countries - just because Australia has a net-zero 2050 target, doesn't mean that is credible. Reasoning from targets is a terrible idea," Lawson says.

Regional opportunities

With this in mind, Lawson points to Europe as a regional opportunity, solely because it is "a more reliable source of decarbonisation as there is a bipartisan commitment to that pathway".

Another interesting region, from an investment perspective, is China, he says.

"China has a very carbon-intensive economy. And it's not because it's decarbonising rapidly. In fact, they probably won't reach peak emissions until 2030," Lawson says.

"However, because the economy is growing quite rapidly, the carbon intensity of that economy is dropping quite a lot each year. And because it has an authoritarian government - which is usually not a great thing, but in this case, it means that once they set a course to net-zero they can continue on that course."

China is one of few emerging economies to have an Emissions Trading Scheme, Lawson explains, and also has very aggressive electric vehicle targets. The country is also important from a broader renewable supply chain perspective as they produce a lot of the technology (and process a lot of the minerals) that go into renewable technologies used globally, he adds.

Sector opportunities

On sectors, Lawson points to transportation as an interesting area for investors to explore.

"There's a huge amount of investment taking place in electrified transportation... That's the area where I think we've seen the most policy change in the last two or three years and also the largest technology breakthrough," he says.

Similarly, hydrogen has emerged as another area of opportunity for investors, Lawson says.

"You have to be careful to sort fact from fiction, but I think hydrogen is clearly one area where again, there's been a lot of innovation taking place," he says.

"Where people feel very confident that this technology can be scaled up quite substantially over time and help that energy transition, particularly in hard to abate sectors like industrial emissions."

A final word on the biggest risk to markets right now

Lawson says that the biggest risk to markets is central bank policy error. After all, nearly every central bank believed the pandemic would be disinflationary. How wrong they were.

"Now a lot of countries have an inflation problem - one that many haven't had in decades. And so central banks have to flip from an environment where as recently as 12 months ago they were focused on providing enormous stimulus to the global economy to now trying to rein it in," he says.

If you look to history, every time central banks have had to make this shift, trouble has ensued, Lawson explains.

"Tight monetary policy will tend to slow economic growth. It tends to raise unemployment. And margins tend to suffer in those circumstances," he says.

"So most investment houses are trying to figure out whether we can get a soft landing. Whether it is possible to get this policy adjustment while keeping the recovery on track, even if it is not as rapid as it was before. Or are we inevitably going to go into a recession in the next couple of years?"

That could see this entire cycle shorten, and ultimately, destroy a lot of commercial value. And in a recession, who thinks long-term? Who beats the drum for climate change when the here and now is so dire?

Want to learn more about Decarbonisation?

Livewire's Decarbonisation Megatrend Series brings you feature articles that go deep on carbon-neutral investing, alongside special episodes of Buy Hold Sell, a megatrend investing podcast and interactive panel sessions with leading fund managers. To visit our Series page, please click the link below.

2 topics

1 contributor mentioned