No evidence of a housing market bottom

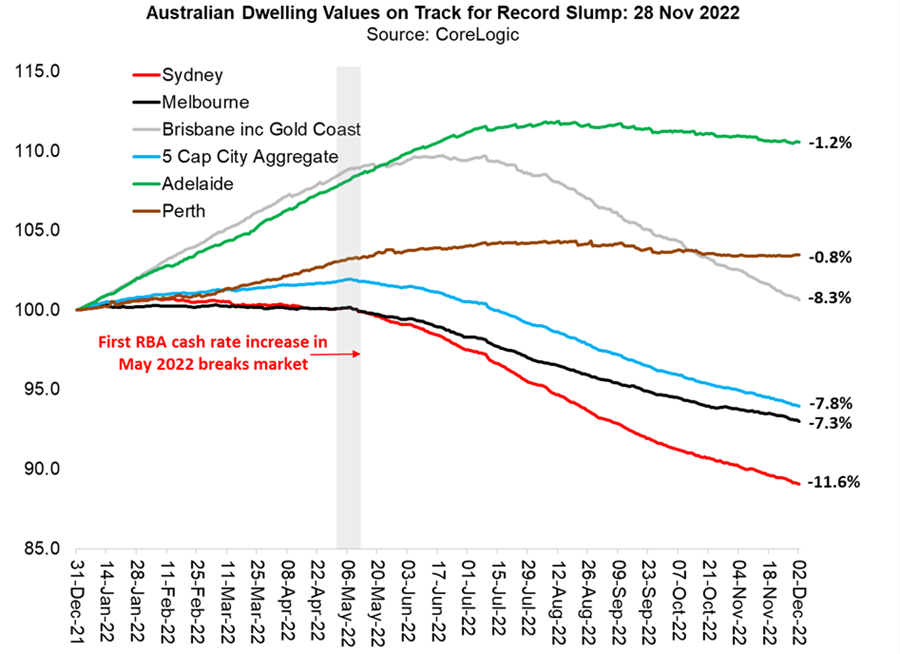

Contrary to the “hopeium” out there, there is currently zero evidence that the great Aussie housing crash is bottoming out. The most constructive thing we can say is that house prices are falling incredibly quickly, albeit at a slightly slower pace than what was recorded a few months ago.

November was yet another incredibly weak month with CoreLogic’s eight capital city index shrinking by a hefty 1.1 per cent. Although this was identical to the rate of decline recorded in October, it was not as savage as the 1.6 per cent loss registered in August.

Across the nation, the unprecedented correction in house prices is playing out at very different speeds: decelerating in some places while accelerating in others.

Ground zero right now is greater Brisbane, where dwelling values are falling at a never-before-seen 2 per cent monthly rate, which has accelerated over the past five months. Since their peak in early July, Brisbane home values have lost about 8.5 per cent in total.

In 40 years of data collected by CoreLogic, the consecutive 2 per cent monthly draw-downs in October and November were the worst months ever witnessed.

A similar theme is playing out in Hobart, where the monthly rate of dwelling price declines has accelerated from a 0.2 per cent loss in June to a chunky 2 per cent decline in November.

If you want to spin a positive story, you could highlight that the house price falls have been slowing in Sydney and Melbourne from a monthly peak of 2.2 per cent and 1.5 per cent, respectively, in July, to 1.3 per cent and 0.8 per cent in November.

‘Harsh reality’

But the harsh reality is that dwelling values in Australia’s two largest cities are still evaporating at an extraordinarily rapid clip. Based on the last two months of data to December 2, Sydney home values are falling at a 14.1 per cent annual rate while Melbourne prices have been melting at a 9.6 per cent annual rate.

It is also telling that the rate of house price losses in both October and November was identical across Australia’s three largest cities: Sydney (down 1.3 per cent each month), Melbourne (down 0.8 per cent a month), and Brisbane (off a shocking 2 per cent per month). This implies that losses are now accruing at a more stable rate.

The case for an RBA pause

Unfortunately, there is more bad news to come. Unless the Reserve Bank of Australia quickly comes to its senses, it is barrelling towards yet another interest rate increase in December, which would mean borrowers have been slugged with a record 3 percentage points of rate rises since May.

To be clear, there is a compelling case the RBA should pause to take stock of the damage it is inflicting on the economy. It claims it wants to be data-dependent, and is not on a pre-determined course, but we have seen scant evidence that the RBA is being anything other than deterministic based on its rubbery forecasts.

The latest monthly inflation data was a massive downside surprise, printing at 6.9 per cent for the year to October compared to the 7.6 per cent expected by hawkish economists. Retail sales contracted by 0.2 per cent in October relative to the 0.5 per cent again optimistically forecast by analysts. Outside of spending on food, sales were even weaker, dropping by 0.6 per cent in the month.

What makes this even more significant is that this data is expressed in “nominal” terms, which means it is boosted by the current elevated rate of inflation. In real or inflation-adjusted terms, retail spending would have fallen even further.

This should come as no surprise to readers of this column, which has repeatedly stressed that consumer confidence is worse than it was during the global financial crisis. Once lofty business confidence has also more recently plummeted.

The latest composite PMI suggests the private economy actually contracted over November. While lagging wages, inflation and jobs data are still firm, they will follow suit in time.

Commonwealth Bank economist Gareth Aird argues that there is a “strong case to leave the cash rate on hold in December given the RBA has already delivered an incredible 275 basis points of tightening over just seven meetings”.

“It takes time for this tightening to impact the demand for goods and services and by extension prices,” Aird continues.

“A further 25 basis point hike in December would mean an unprecedented 300 basis points of rate hikes over just seven months. The RBA is still flying blind to a degree given the last few rate hikes have not yet hit home borrowers from a cash flow perspective (at CBA there is on average a three-month lag between RBA rate hikes and when a borrower on a minimum mortgage repayment schedule experiences an increase in their mortgage payment).”

‘Fly in the ointment’

As we pointed out last week, the fly in the ointment here is that almost one-in-four home loans (by value) will switch in 2023 from ultra-low fixed-rates set at between 1.75 per cent and 2 per cent to rates that are more than double these levels at circa 5 per cent to 6 per cent.

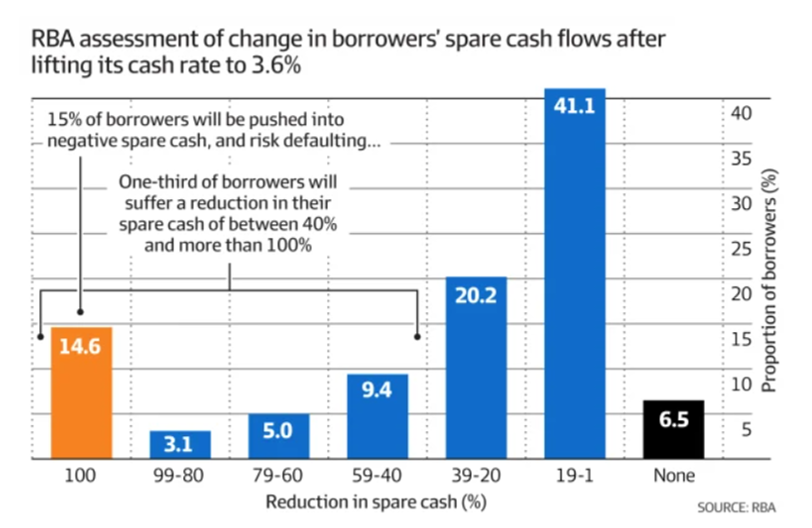

According to the RBA’s own analysis, more than 52 per cent of all borrowers will see their “spare cash” decline by between 20 per cent and more than 100 per cent, assuming its target cash rate climbs to 3.6 per cent. Spare cash is defined by the RBA as the income the borrower has left over after meeting mortgage repayments and “essential living expenses”.

A staggering 15 per cent of all borrowers will have their spare cash turn negative in the RBA’s base case. That means they are at a very serious risk of defaulting on their loan repayments. Almost one-in-four borrowers will see their spare cash shrink by between 60 per cent and more than 100 per cent. And around one-third will have their free cash reduced by between 40 per cent and over 100 per cent.

So right now there is really no good news on house prices. The pain is set to continue for many more months to come unless the RBA swings 180 degrees and starts cutting interest rates, which nobody expects in the very near-term.

In Sydney, home values have fallen almost 12 per cent peak-to-trough. Across the five largest cities, the losses have accumulated to about 8 per cent. Brisbane prices are down roughly 8.5 per cent (and falling at 2 per cent each month). Melbourne properties are off 7.5 per cent.

In October last year, we argued that national home values would correct by between 15 per cent and 25 per cent after the RBA commenced raising rates. At the time, no mainstream analysts were forecasting material price falls. The previous record for Aussie house price losses was between 10 per cent and 11 per cent from 2017 to 2019, which we should surpass in about March.

Importantly, one should not necessarily expect a super-strong bounce in prices once the RBA finishes its dirty work. It will really depend on when it cuts rates, and by how much.

If it does not reduce rates, prices will not appreciate until purchasing power dictates they should. And with no interest rate relief, purchasing power will be driven by income growth, which tends to be a slowly moving beast.

First published in the AFR here.

2 topics