No such thing as passive

Key Points:

• There is no such thing as a truly passive investment strategy.

• Choosing to invest in a market cap weighted index tracking product is still an “active” choice, and is only one of many decisions that an investor must make.

• Indeed, those other decisions, which are much harder to ignore, will have a much greater impact on investment outcomes over time.

What does it mean to be passive when investing? In this month’s Insight we outline our thoughts on the concept and some of the confusion and misconceptions stemming from it. We don’t think any investor can be truly “passive”. Because passive investment has become so popular and widespread, it has for many taken the mantle of a risk-free decision. We strongly disagree with this, there is no risk-free position in investment management and every decision (even the decision to not make a decision) has consequences.

Market Cap, Quantitative, Fundamental or a Dartboard?

Most commonly, a passive investment strategy refers to an investment product which replicates the performance of a market capitalisation weighted (cap weighted) equity market index. A cap weighted strategy weights the securities in the portfolio by market capitalisation (the total value of a company’s shares). The largest companies get the biggest weight. Quite simply, you are buying a slice of the overall market. A benefit of this approach is the very limited need to rebalance. The weight of individual names in the portfolio will grow and shrink with their respective market moves. The huge amount of money invested in market cap strategies and their simple implementation makes their fees lower than more complicated investment strategies.

Low fees and strong performance versus alternatives since the Financial Crisis have made market cap allocations an attractive option for many investors. Despite this, the academic and empirical support for passive is relatively mixed. S&P data (SPIVA Scorecard) shows that most active managers have underperformed their respective benchmarks after fees over the past decade. However, academic research has also shown that even most random portfolios will outperform market cap in a back test. How is this inconsistency possible? Well, it turns out that the small cap and value styles of equity investing (effectively the antithesis of market cap, which holds big, expensive companies) have such strong performance effects over time periods greater than the past decade that simply by having some exposure to these factors a random portfolio should outperform the market cap benchmark (1).

We think in practice, most of the swings and roundabouts between the relative performance of active and passive styles has more to do with the overarching investment environment than anything else. Market cap indexes have the biggest weight in the biggest companies. That means when the largest companies are doing well, market cap indexes will do well. The period following the Financial Crisis, which involved a substantial concentration of market power in the largest US technology companies, has been a phenomenal return period for the largest companies and therefore market cap weighted portfolios relative to their alternatives. Since 2021, we have seen a partial reversal of that trend, with value managers in particular doing well as real interest rates have risen.

As active asset allocators, our role is to determine which style should perform best given our view of the investment environment and to select which strategies align with that view. If that view suggests an active style, we will try and find one of the few that consistently outperform market cap. Like picking stocks, picking between active managers or market cap strategies is a difficult exercise which takes considerable skill.

The Elephant in the Room

Most will be aware that there has been lots of focus and conversation on passive versus active management and the various performance of different equity styles through time and fee savings et cetera. Having been happy to participate in that debate and share our view above, we now need to turn to the aspect of investment decision making which actually drives the vast majority of outcomes – asset allocation. Often, investors will prosecute a debate about picking active equity managers versus passive index trackers seemingly endlessly and give very little airtime to how much equity exposure they actually need in their portfolio versus other asset classes. What should their regional exposure be? Should they employ a tactical asset allocation process? Focusing entirely on building the equity allocation in a portfolio, risks fiddling while Rome burns.

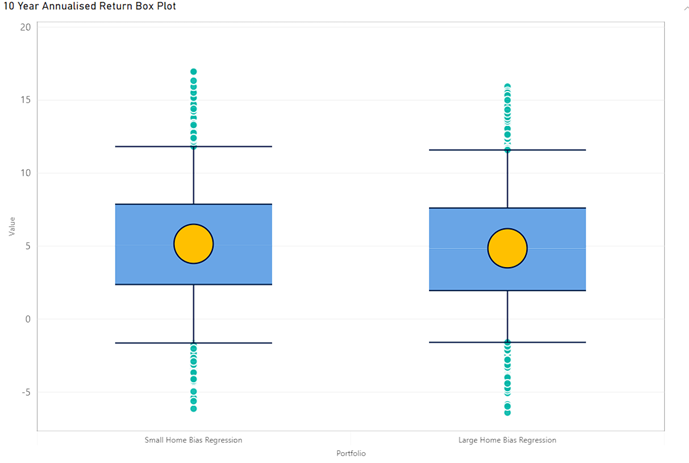

Unfortunately for investors hoping to employ a passive investment decision making process, there is no option to passively determine an asset allocation. With multiple asset classes and multiple decisions within each asset class required, someone needs to make a call on the appropriate portfolio. From an Australian investor’s perspective, even constructing the notionally simplest portfolio possible – a 70/30 equities/bonds portfolio split between Australia and the rest of the world comes with important decisions. Below, we show the results of our capital market simulation model on two versions of the above portfolio – one with a small home bias (~1/3rd Australia) and one with a large home bias (~2/3rds Australia). Between the two portfolios there is a 30-basis point difference in expected returns at the 50th percentile. The small home bias portfolio also has a fatter right-hand tail in its distribution (more potential upside).

Source: Drummond Capital Partners

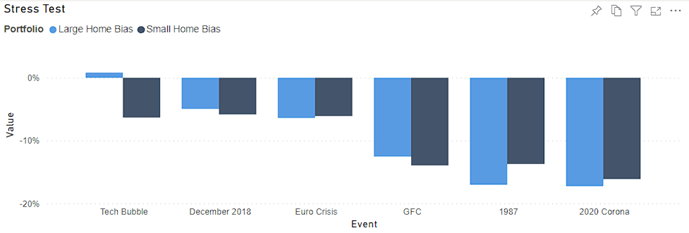

The difference between the two portfolios is even more evident when looking at historical market drawdowns which lead to varying performance outcomes. A large home bias was beneficial in the Tech Bubble and Financial Crisis. A small home bias was preferable in the 1987 crash and the Covid recession (see below). Once other asset classes are introduced, the decision-making process becomes even more important (and complicated).

In line with the above, while some could argue that an investor can be passive when deciding the makeup of their equity portfolio, there is no way to be truly passive from an asset allocation perspective and this is the most important decision.

Set and Forget?

Once an investor achieves an asset allocation in some form, they must then decide what to do from that point. What does it mean to be passive in this context? Picture a scenario where via some kind of divine inspiration a 30-year-old allocator develops an asset allocation appropriate for their stage in life and the long-term investment horizon. Being passive implies allocating to the portfolio, perhaps contributing regularly, and then returning 35 years later having achieved their objectives. Of course, this ignores the fact that there is a portfolio that needs to be managed through this time.

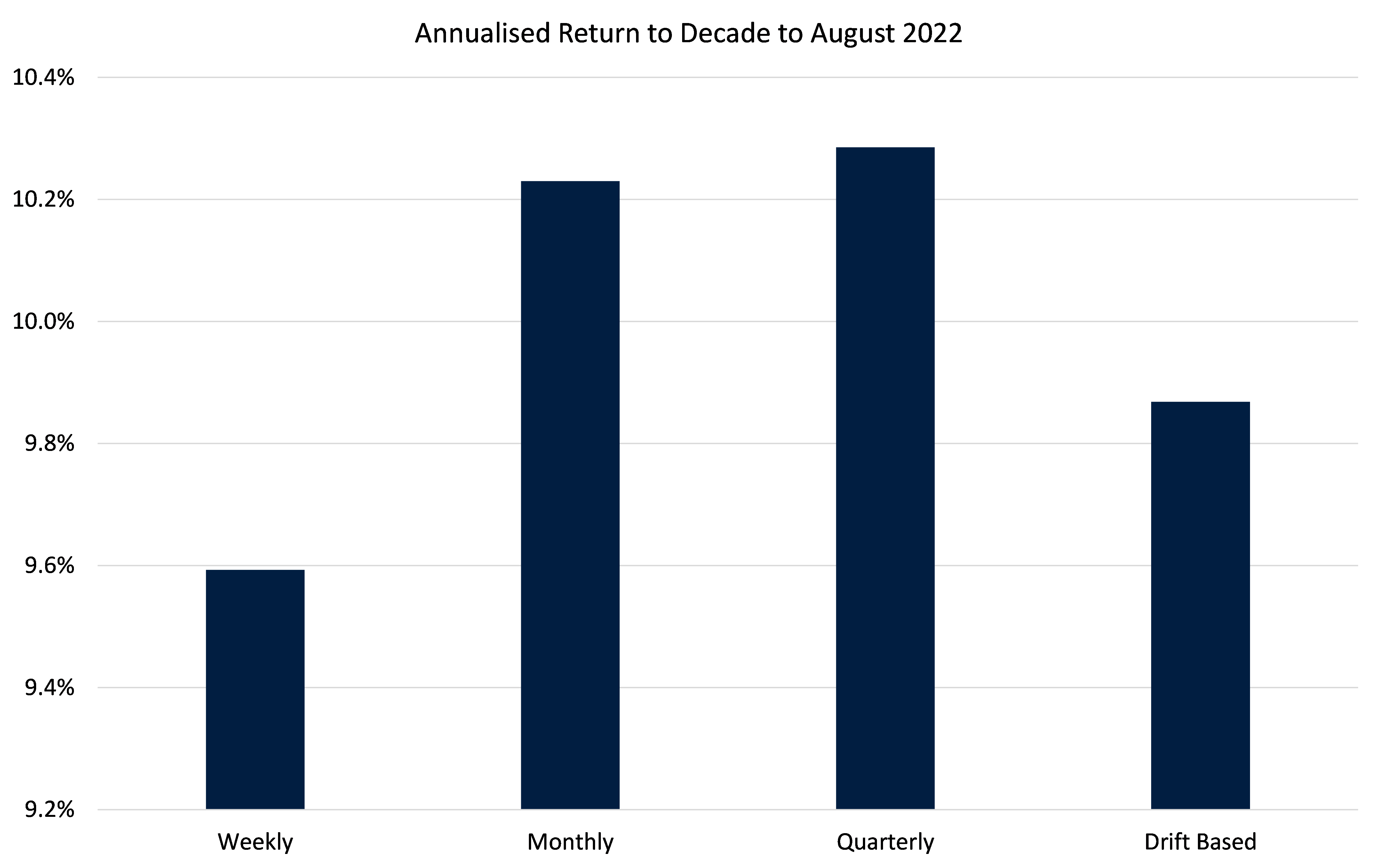

Even a passive portfolio requires some maintenance. Different investments rise and fall by varying amounts, implying some rebalancing is required. A 70/30 US equity/US Bond portfolio incepted in 2012 would have become an almost 90/10 portfolio ten years later due to market moves. Unfortunately for those wishing to be passive, even rebalancing requires a decision. Below, we show the impact of rebalancing this 70/30 portfolio across different time horizons and via a drift-based rule (if either asset class moves 2.5% away from target, both asset classes are rebalanced to target). Which rebalancing rule the investor chooses has a material impact on annualised performance over the past decade. Like equity styles, the rebalancing rule that performs best depends on the investment environment in which you are operating in. Trending markets favour infrequent rebalancing, volatile markets the opposite.

Beyond rebalancing, clearly a passive investor won’t be employing a tactical/dynamic asset allocation process. As active asset allocators, we think there is value in actively managing portfolios on behalf of investors, though we are peddling our wares by saying so. At the very least, we think it is worth having someone paying attention to what is going on in markets and managing the portfolio accordingly. If they can add value by taking advantage of positive market environments or reducing risk in negative market environments (ideally both) all the better.

To get a feel for how much that potential decision matters, we have undertaken some simulation analysis to show the impact on annualised portfolio returns from an active decision-making process assuming a fixed hit rate (2). Specifically, the simulation begins with post-1990 quarterly returns for US bonds and US equities. We then create 10,000 random portfolios, where the probability of making a “good” active decision in any given quarter is 52.5%. In other words, 52.5% of the time, the portfolio allocates a 2.5% long position in the highest returning asset and a 2.5% short position in the lowest returning asset and 47.5% of the time, the long position is allocated to the worst returning asset and vice versa. Basically, we are simulating what is achievable from a portfolio perspective if an active asset allocator is correct 52.5% of the time. On average, the investor who gets that decision correct (2.5% position between US bonds and equities 52.5% of the time) since 1990 over 10,000 simulations generates an annualised excess return of 1.3%.

This analysis of course oversimplifies the problem. There are more than two asset classes. Active position sizes are often smaller than 2.5%. Few portfolios are truly long/short. The relative outperformance of each asset class in each given quarter matters a lot. If your wins are more frequent, but much smaller than your losses, this can also materially deteriorate investment performance. Regardless, we believe that the key point is instructive. If you can make good decisions and make even only moderate changes to asset allocation, the impact on long term performance is meaningful.

Portfolio Positioning

As readers can probably gather, we actively manage our portfolios and think that is the most beneficial and responsible way to fulfill our fiduciary duty. Aiming to be pragmatic in our decision making, our portfolios will contain active and passive strategies, with the decision based on whether we think that is best at the time rather than a dogmatic view which forces a choice between one or the other.

At the moment, our portfolios remain underweight growth assets, reflecting our expectation that major developed markets will experience a recession in the year ahead.

(1) (VIEW LINK)

(2) Hit rate refers to an investor’s ability to make a good decision versus a poor decision

1 topic