Not all private credit is created equal: How to pick the winners and avoid the losers

In Australia, private debt assets under management have grown at more than 100% per annum over the last two years[1]. This explosion in popularity has been met with an equally staggering increase in the number of private credit funds vying for investor capital. Morningstar’s Private Debt category had fewer than 10 funds in 2018. This number had ballooned to 42 by the end of 2022.

However, private debt is a broad category where the credit quality and structure of the underlying assets can vary wildly between funds. This has proved to be an issue for investors aiming to thoughtfully allocate to the growing asset class. Comparing the risks and potential returns between funds is a challenge.

Despite being pitched as the newest invention in funds management, private credit investing is more than four decades old. Shifts in bank lending standards fuelled significant growth in the US private debt markets in the 1980s and 1990s.

This most recent resurgence, however, has been driven by the efforts of Australia’s banking authorities to make our domestic institutions the safest in the world. The well documented consequence of this capital regime has been the prioritisation of mortgage lending at the expense of business banking. This move to a homogenous bank borrower profile has left large swathes of the economy without access to critical financing.

Small and medium sized businesses, property companies and agricultural operators are facing a stark funding gap. With traditional banks not meeting their specific needs, specialist lenders have poured their capital in to fill the void.

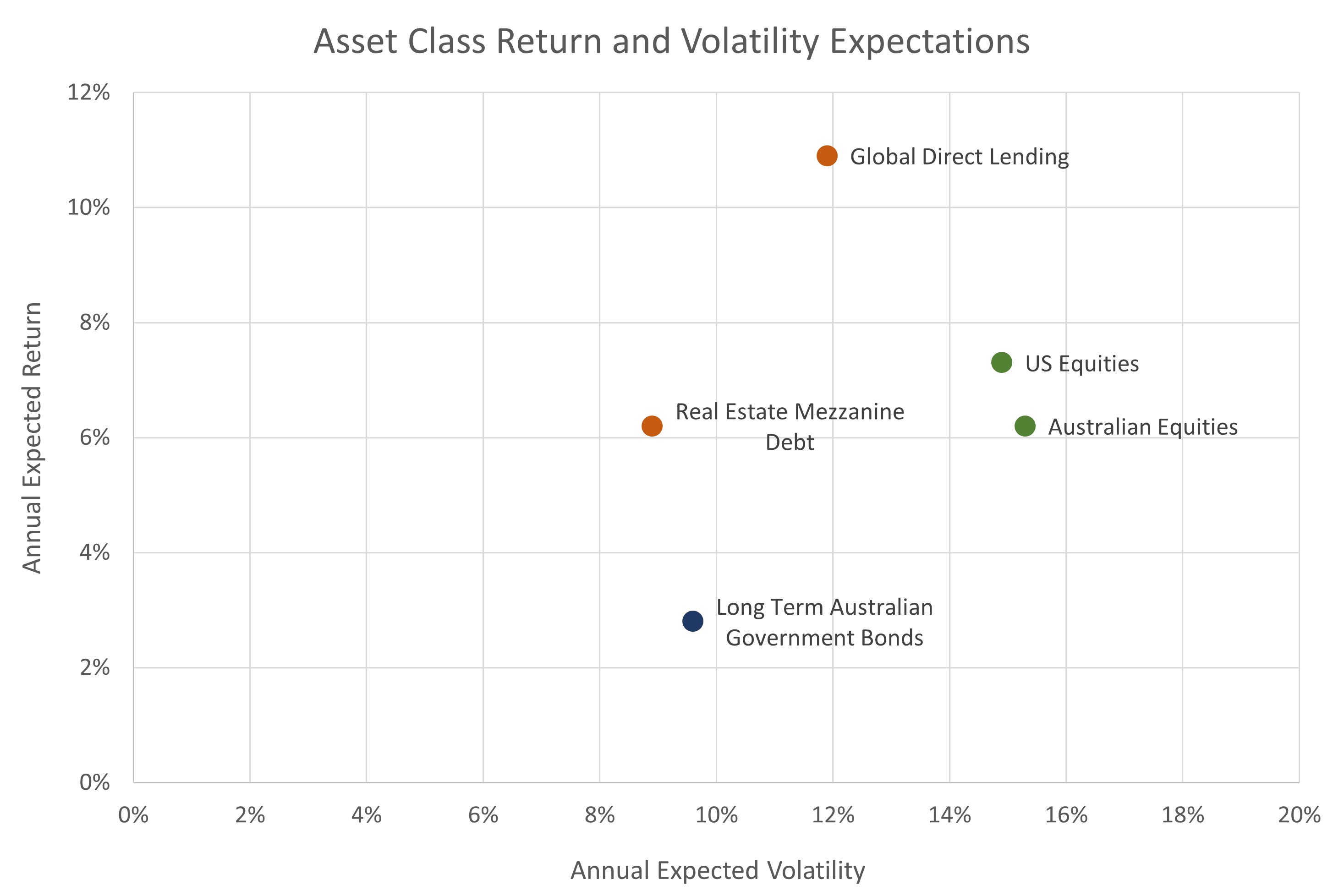

The risk and return

dynamics of the asset class can be extremely compelling, offering upside performance

akin to equity markets, but at levels of volatility that are lower than

traditional fixed income assets. Institutional investors have long appreciated

this, but not until more recently has the sector been able to cater to smaller

investment balances.

For all its fame and fortune however, private credit remains an ill-defined and relatively opaque asset class. As previously mentioned, the types of loans and level of risk varies greatly between managers and their strategies. Meanwhile, confidentiality agreements strictly limit the availability of public loan level data. This makes any fruitful comparison between funds difficult.

Additionally, a synchronised reset in the interest rate policies of the world’s largest economies has caused many to signal challenging times ahead. A meaningful economic downturn would act as the first real test for Australian private debt since retail investors allocated their capital en masse.

Interestingly, times of market dislocation actually create significant opportunities for private debt managers, who can negotiate asymmetric loan terms. However, the ability of a fund to capitalise on difficult markets will be largely driven by its ability to protect capital through the cycle.

The challenge is no longer how to access private credit markets, it's how to appropriately compare private credit funds.

Traditional measures of risk are often grounded in the fluctuations of observable market prices. Judging risk in private markets is a more nuanced art form. The limited amount of available information and the lack of an unambiguous benchmark makes it difficult for this risk to be easily assessed.

Take the advertisement atop this article for Guaranteed Capital’s latest private debt deal. It offers a 9.25% return in just 18 months. At an 80% LVR, asset prices can effectively fall 20% before the debt is impacted. The phrase “first mortgage” also creates a sense of security. As the firm’s name suggests, this sounds like a sure thing.

What’s lacking is the detail required to critically evaluate this opportunity. More comprehensive due diligence would uncover that the LVR is based on the expected value of a property development upon completion, not what the land could be sold for today.

Additionally, it turned out, upon closer examination, that our fictitious debt manager Guaranteed Capital also owns the property development and construction company undertaking the work. This is a conflict of interest for the administrator of the loan and fundamentally compromises a key risk control for investors.

Even though Guaranteed Capital is a fictitious firm, it strikes a worrying resemblance to many actual schemes successfully soaking up investors’ funds. The challenge facing investors is no longer how to access private credit markets, but instead how to evaluate and select the most appropriate private credit funds.

Comparing Funds Using a Private Credit Risk Matrix

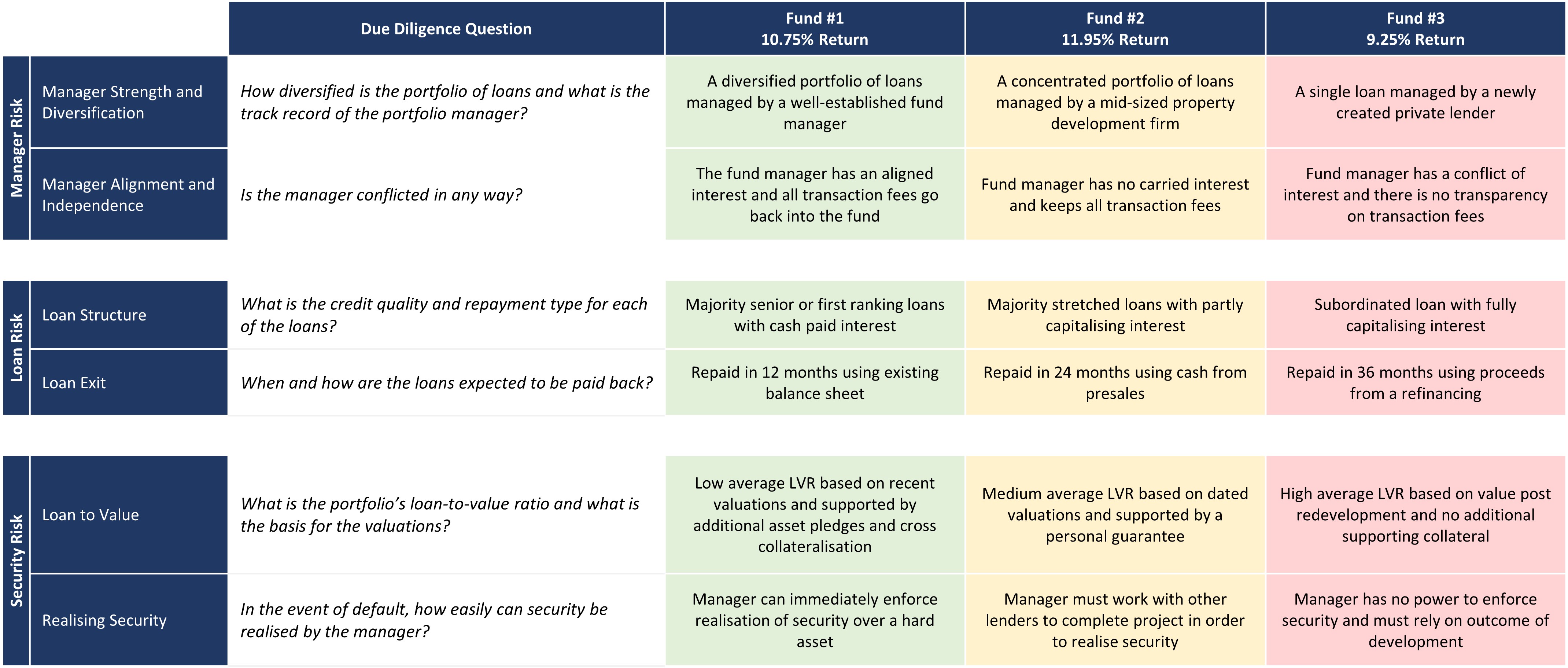

Investors hoping to complete this task can take a practical risk matrix approach to their analysis. The below example offers six due diligence questions across three risk areas that aim to dive deeper into some common components of private credit managers. It can be used to compare a variety of funds, from single asset offerings to diversified portfolios.

Below is a brief explanation of each of the principal risk areas.

Manager Risk

The expertise of the fund manager in portfolio construction and asset management is key. The investment vehicle should provide appropriate diversification and have proven ability to manage concentration and liquidity risks. Another important question here is the independence of the manager and the potential for conflicts of interest. Is there any instance of the fund manager carrying a direct or indirect interest in both the debt and equity? This type of conflict can distort priorities and even magnify losses if things go wrong.

Loan Risk

The loan risk explores the components of the portfolio of loans. It includes the credit risk of the borrowers, quality of collateral and loan covenants, seniority, tenor and exit plan. Portfolios hold loans in all shapes and sizes, but certain structures carry additional risk and warrant a higher return.

Security Risk

When investing in credit assets, security trumps all other risks. Beyond the often-quoted loan-to-value ratio (LVR), investors should consider the type and seniority of security and the ability of the fund manager to realise that security. In the event of default, enforcement of security over certain types of assets can be complex, costly and time consuming.

Three hypothetical

investments strategies have been included as an example.

It’s important to highlight that this exercise is not intended to provide an absolute measure of risk, only a relative one. Similarly, this is not an exhaustive set of due diligence questions but rather a subset to help investors compare funds. Investors will no doubt have their own non-negotiables when deciding to invest alongside a particular manager. Additional work should always be completed, and relevant financial professionals consulted prior to investing.

Private debt strategies do not share a common universe of loan assets to select from. Instead, they rely on the origination networks of the manager. This results in a disparate and inefficient market that disturbs the traditional relationship between risk and return.

As the hypothetical examples in the risk matrix suggest, there will be instances where investors can simultaneously reduce risk and increase return by selecting the right fund. Alternatively, they should ensure they are getting duly compensated for any additional risk they knowingly choose to take on.

In good news for investors, private credit strategies can be defensive in nature while also delivering strong relative returns. Additionally, they represent significant buying opportunities when market dislocations occur, meaning there is merit to the recent influx of interest.

By asking the right questions and working closely with their professionals, investors can hopefully identify those private debt funds that will outperform through the cycle.

[1] Preqin Pro, Australian Private Capital Market Overview: A Preqin and Australian Investment Council Yearbook 2023, April 2023.

5 topics