Numbers from today and stories about tomorrow

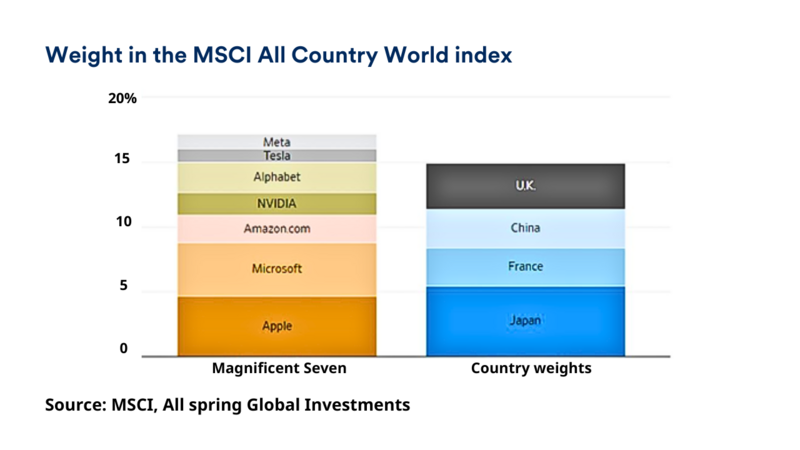

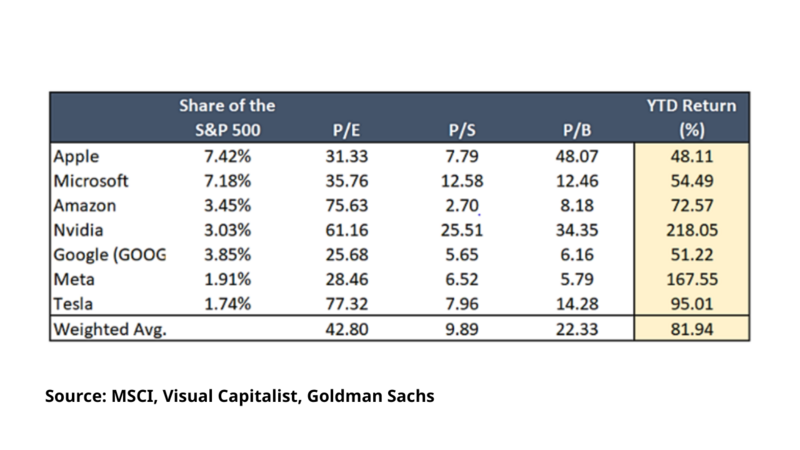

Optimism rules. Relatively lofty market valuations, risks of recession in the face of rising interest rates and escalating global conflict have proven no match for optimism on the prospects for technology and artificial intelligence. Mega cap technology underwrote much of the 24.2% gain in the S&P500 over 2023 and technology more broadly powered a 43.4% gain in the NASDAQ (the best since 1999).

While pedestrian in comparison, the 12.4% total return for S&P/ASX200 in 2023, split fairly evenly between industrials and resources, was strong. These returns were very close to the equally-weighted stock returns in US markets (again illustrating mega tech dominance). Much of the good news came in the final quarter of the year as the prospect of interest rates beginning to retrace a little triggered renewed optimism. You know the optimists are in charge when interest rates rising is not a reason to sell stocks but the potential they may go down a bit is a great reason to buy them.

The resilience of markets raises the question of how important interest rates really are to equity market valuations.

One does not have to dig too deeply to find evidence which doesn’t sit comfortably with the narrative of equity market valuations being tied tightly to interest rates, as a large group of well-informed investors rapidly and effectively assimilate new information in market prices. UK short-term interest rates are almost identical to those prevailing in the US. While cash rates in Australia remain below both the UK and US markets, 10 year bond yields across all three markets are not dissimilar. While fixed income investors share similar prospects, equity market investors are looking through a different lens. The price earnings ratio of the FTSE100 in the UK sits a little over 10, while the S&P500 sits a little over 24 and the NASDAQ a little over 32, with the Australian market between the two at around 16.5. Japanese stocks are anchored to interest rates which remain anchored close to zero and trades a little under 20 times earnings. Seeing a pattern? I’m not. Investors in some equity markets are prepared to accept an earnings yield below that on a (purportedly) risk free asset while others want a traditional 4-5% risk premium or more.

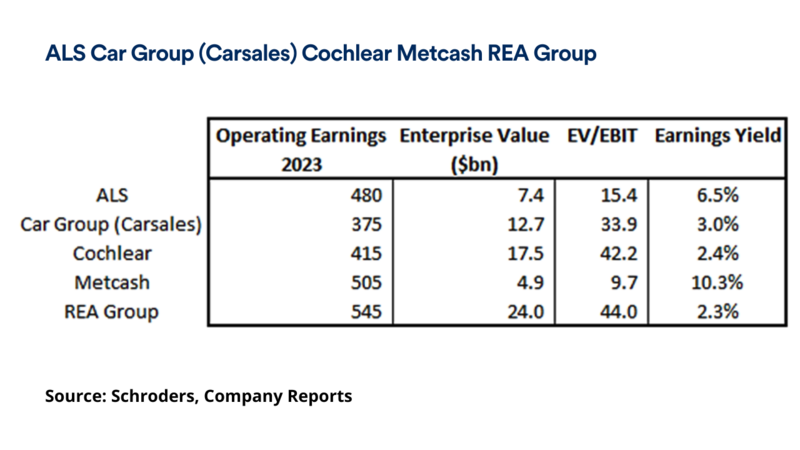

Patterns below the headline ratios are similarly tough to interpret. The random collection of Australian companies with relatively similar levels of operating earnings in the table below shows gaps in operating earnings yields you could drive a truck through. One could suggest that if your business makes about $500m you should be able to float it on the ASX for somewhere between $5bn and $25bn. Not exactly narrowing things down!

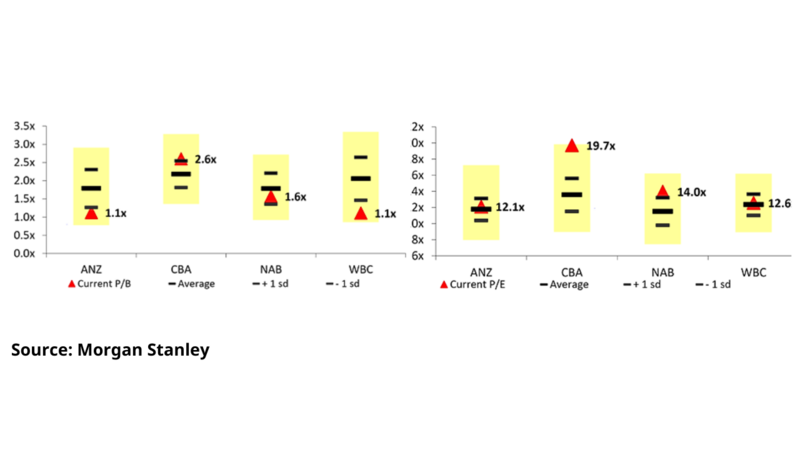

Even if we choose businesses with a very high degree of homogeneity, things are tough. Different coloured logos aside, the businesses of the 4 major banks are remarkably similar. Valuation multiples at both a price to book and price earnings ratio are far less aligned.

In reality, equity market valuations are a crowd sourced result with only a small amount of the crowd applying much science at all. Morgan Housel wrote a brief article a few years ago titled “A number from today and a story about tomorrow” making the point that investment valuations, economic and political outlooks are a number we know multiplied by a story we like. We can apply great diligence in validating a number from today. The financial position of a company, the extent to which earnings are supported by cashflow, how profits are earned; all these variables succumb to the desire of many (including us) to be data driven. When it comes to the market prices and valuation which underly investment performance, it is the story about tomorrow that matters most. Buoyant liquidity conditions tend to accompany very rosy stories of tomorrow. These stories are ebbing and flowing as wildly as ever. The AI and data solutions story which drove Appen (ASX: APX) to a $5bn valuation has waned to about 2% of this level; a similar story for Pro Medicus (ASX: PME) has waxed to $10bn (about 80 times 2023 revenue) and added about $4bn over 2023.

Though the volatility which accompanies investing in businesses selling commodities/materials dissuades many, we have historically approached the sector with a different lens. While commodity and commodity stock prices will swing wildly, the longer term threats from disruption are low. Cost position drives returns. Most will be necessary forever and finding new, high quality resources isn’t getting easier. For anyone doubting the importance of materials in our future, Ed Conway’s ‘Material World’ might change your mind. Additionally, production costs and the cost of new supply have generally been fairly reliable indicators of future price direction. When prices are substantially higher than incremental costs of new production they will come down, and vice versa. 2023 has been tougher than many on this front. In lithium, things have followed the script. The expected growth in electric vehicles and battery storage together with difficulties in adding supply was (and remains) a persuasive narrative. Unfortunately, with spodumene prices above US$5000/t and lithium carbonate and hydroxide at US$50k/t, any anchoring to production costs disappeared. Price forecasts were nothing more than guesswork anchored on prevailing prices. Rolling forward 12 months and spodumene and lithium prices are down 80% and cost curves are back in play. Higher cost operators such as Core Lithium are reviewing operations, a necessary process when expenses exceed revenue. In this light, the collapse of the Albermarle bid for Liontown Resources (ASX: LTR) in October due to complexities (otherwise known as Gina Reinhart) was one of the great get out of jail free cards. When implied long-run commodity prices lose connection with any reasonable expectation of costs, risks are elevating sharply. While pricing of lithium stocks has adjusted to some degree, valuations are hardly pessimistic. At the depths of despair in 2015/16 the lowest cost iron ore producers such as BHP Billiton (ASX: BHP) and Rio Tinto (ASX: RIO) traded around NTA backing and vastly below replacement cost. Good quality but not lowest cost producers such as Pilbara Minerals (ASX: PLS) are about triple these levels currently. Most expect current prices are anomalous and the future should be much brighter. This story of the future is more than possible; there are alternatives however.

Though cost curves may have proven useful indicators of price direction in lithium, they have led us up the garden path elsewhere. Most notably, from price levels already near the top of the cost curve, iron ore rose another 20%, largely in the final quarter. BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto price performance followed suit and Fortescue Metals (ASX: FMG) shot the lights out. Our lack of exposure in this area was costly. Opining on the reasons behind this price spike is fraught with danger, however, whether the Chinese engine room which converts the ore into steel finds an outlet domestically (increasingly tough given a challenging property market outlook) or through exported steel, it is only when profits disappear that demand tends to go with it. Nonetheless, a resilient Chinese demand picture is an undeniable positive for Australia as much of the value creation is passed back up the chain. While valuations premised on profit per tonne of something like a third of the levels achieved at current pricing may seem conservative (and underly views of business value below current market prices for most iron ore producers), stories can change quickly. Using cost curves as an anchor for valuation may not always work, however, when the alternative is extrapolating current prices we’ll take the anchor over the cork in the ocean.

Lack of an anchor is sometimes an insurmountable problem. In the tug of war between the store of value for young people (bitcoin) and the store of value for old people (gold), there was a rare win for inter-generational equality. The oldies got smashed. Bitcoin gained a lazy 155% over the year, leaving the 13% rise in the gold price looking mundane. We have continued to sit on the sidelines in businesses associated with either enterprise.

Using enormous amounts of energy and moving enormous volumes of rock to deliver ‘stores of value’ which are premised on a lack of value in use is a tough sell. In a world needing to eliminate waste and unnecessary energy use and replete with opportunities for productive uses of capital, these do not appear good examples.

When it comes to stories, the slide presentations on most M&A deals usually have some of the best fairy tales. 2023 ended with a flurry. The rejection of the Brookfield EIG offer left Origin Energy (ASX: ORG) as a public company, a decision we supported. In illustrating how a Board and management should act in a takeover offer, we thought it exemplary. The valuation of a complex collection of assets including stakes in APLNG stake (one of a number of large and perhaps ill-considered LNG investments to export Australia’s East Coast gas resources), a highly successful technology investment in Octopus Energy, a large retail customer base and power generation fleet is complicated and of course subject to opinions on the future. While many disagree, we remain of the view that the energy transition will require higher prices and a larger profit pool in order for decarbonisation to be pursued effectively. Comparing costs where much of the investment is sunk by businesses and households (as has obviously been the case in solar) with the cost of traditional generation (with no capital cost shifted elsewhere) is comparing apples and oranges. True cost analysis of wind, solar and batteries is further complicated by uncertain duration assumptions. While we know nuclear facilities will last many decades, it is highly unlikely wind, solar and certainly batteries, will go anywhere near matching this duration. Ignoring the importance of duration is costly, with examples such as building quality (leaking pipes and escalating insurance cost), and transferring road building costs to consumers in the form of toll roads highlighting the true long-term impacts.

December also saw a $2.1bn bid for Link from Mitsubishi UFJ, ending a tumultuous few years after yet another disastrous foray by an Australian company in the UK (Billiton, NAB, Bunnings, Ramsay Healthcare to name a few), the surprise reverse listing of Chemist Warehouse through Sigma (ASX: SIG) and Orica (ASX: ORI) spending $550m on Canadian technology roll-up, Terra Insights. On the latter, our scepticism suggests large explosives companies are generally not great homes for private equity technology roll-ups (not sure there is a good home) and 15x EBITDA is a price which requires the future to have a fairy tale ending. The synergies when large and often inefficient companies buy smaller and leaner peers tend to appear on the slides and evaporate in real life. On Chemist Warehouse (CWG), the deal structure in which CWG receive 85.75% of Sigma and $700m means the rump of Sigma doesn’t matter much. The owners have undoubtedly built an amazing business. Ongoing domestic expansion in an industry still protected by outdated and unnecessary regulation offers significant appeal, and the path of public company success stories such as Bunnings, JB Hifi, Lovisa and Premier makes early enthusiasm for the transaction readily understandable. While international expansion is a more polarised list of winners and losers, starting with a management team who clearly know how to make money is a better than average starting point. A volatile but generally solid few years for most retailers and an unusual deal structure means not that much is known about the numbers from today. An easy story to like means the number which investors are prepared to pay for the future is high.

10 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned