Numbers over narrative

There’s an old joke about one person asking another how to get somewhere. The answer: “First off, I wouldn’t start from here.”

That punchline works for an investor looking for a decent return from the highly priced S&P500 because you really wouldn’t want to start at this level. Valuation drives long-run equity returns. With the expected return going down as the valuation goes up, an investor should aim to buy when cashflows are under rather than over-valued. This may be obvious, but it’s an obvious that many have forgotten.

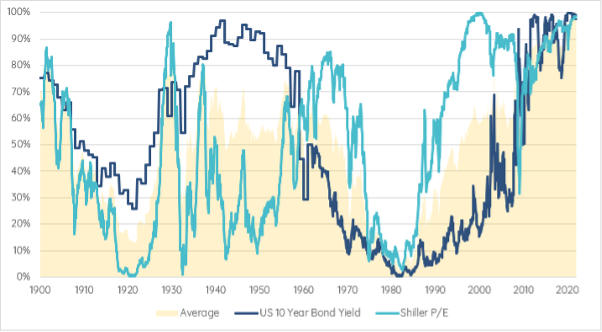

Robert Shiller, a Nobel Laureate economist at Yale, provides data and graphics for his Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings (CAPE) which is the S&P’s current price divided by the 10-year inflation adjusted moving average earnings. At the end of February, the CAPE was in the 98th percentile of history, which, apart from the tech bubble, is about as high as it’s been since 1880 (chart below).

Shiller Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings and Bond Valuation (Percentile)

At today’s level, the 10-year expected return from the S&P500 (assuming margins stay at today’s record levels, the index holds its lofty valuation and the average sales growth of the last 20 years is achieved) is less than 4% nominal which is a small number in anyone’s book.

In December 1999, a popular explanation for the all-time high CAPE was that you couldn’t put a price on Tech shares that were changing the world.

This was another unhelpful rationale: an investor who bought the S&P500 at the start of 2000 had lost more than 4% ten years later. There’s a reason that they refer to the noughties as the lost decade.

However it’s not all bad news. There are still attractively valued individual shares in the US if you look for them, other regions are less expensive, and income can help. However, it’s important to understand the starting point - and for investors in US shares today it’s not a good one.

Is the market blind to the numbers?

Let us repeat one more time - market participants spend too much time on forecasting and too little on positioning (who owns how much of what).

Positioning in US Government Bonds is particularly important because they provide the risk-free benchmarks that investors use in pricing other assets, hence the argument above that low long-term rates justify high equity valuations. That this narrative has been accepted can be seen in the fact that – like equities - bonds stand at their 98th percentile valuation since 1881 (chart above). 60/40 has never offered such low prospective returns nor risk.

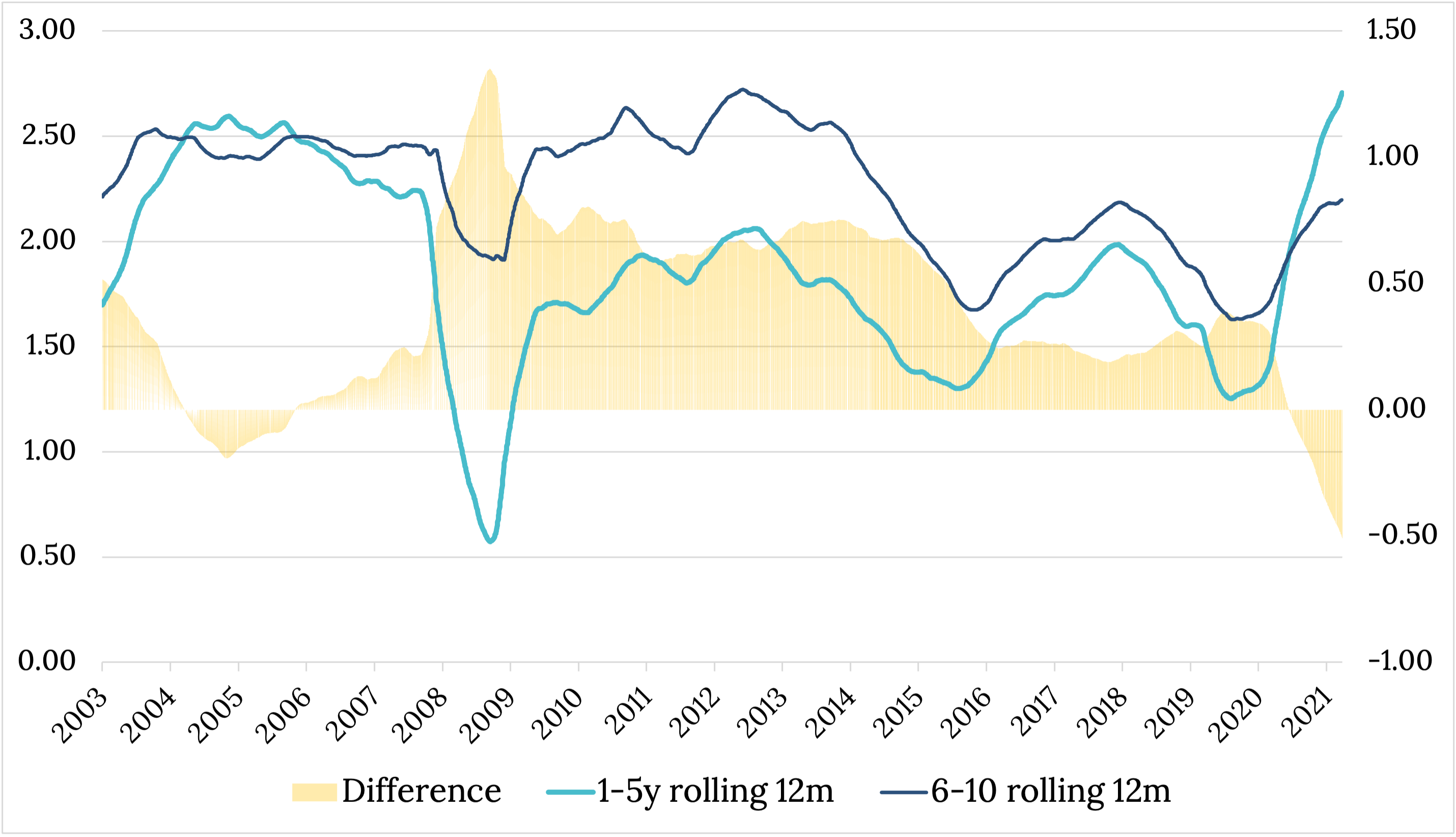

Despite inflation reaching levels not seen since the 1980s when acid-wash jeans and shoulder pads reigned, investors in Treasuries remain unmoved by the idea that this material pick-up will be anything other than short-lived. For example, twenty years of data, which predict average expected inflation over the next decade derived from US bond prices (chart below) show:

- Average inflation priced into US bonds for years 1-5 is 3.5% and years 6-10 is 2.2 %.

- Although 3.5% is the highest over the period, the 6-10 year is well within the range.

- It’s unusual for near-term to be priced higher than long-term inflation and the difference between the two has not been wider over the period.

- This suggests that the market is confident of the Fed correcting what it sees as a modest short-term policy error.

US Treasury Market average inflation expectation for years 1-5, 6-10 and the difference

-

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve, Talaria Whether these expectations are reasonable is far less important than the fact that they exist, because they are the foundation upon which investors have built a tolerance for the lofty US equity market valuation we described above. When investing in an expensive US equity, it’s important to understand the risk being taken on. A share, ETF, or Index fund may have a wonderful story attached to it but most of its price action may be explained by the direction of the bond market.

Moreover, even if current fixed income positioning proves prescient, a good outcome would still only be that the S&P 500 delivers a decade of poor average returns - because the maths says it must.

The good news is there is a solution to this challenge, and one we’ve been talking about for some time – Diversification. I will go into more detail on where and how to diversify next time but to summarise:

It means embracing income as a component of return, value as a factor, regions other than the US and sectors other than Tech. Doing this will by definition reduce the concentration risk to which so many investors are exposed. It will also increase alignment to areas of the market that promise meaningful upside.

5 topics