Outperformance. All companies try, but few achieve it

Total shareholder return or TSR - the appreciation in the share price plus dividends - is a measure of corporate performance. Relative TSR pitches the corporation’s TSR against a benchmark. It’s used frequently by companies to measure their own performance, and it is used to determine executive long term bonus awards.

McKinsey has examined the 1,000 largest corporations in the US by market capitalisation and measured how many made it into the top decile of companies relative to the market over a 10-year period. They considered three different periods, the 10-year periods ending in 2012, 2017 and 2022. Over these three periods, a top decile company typically had to beat the market TSR by 20%.

Very large doesn’t invariably mean very good

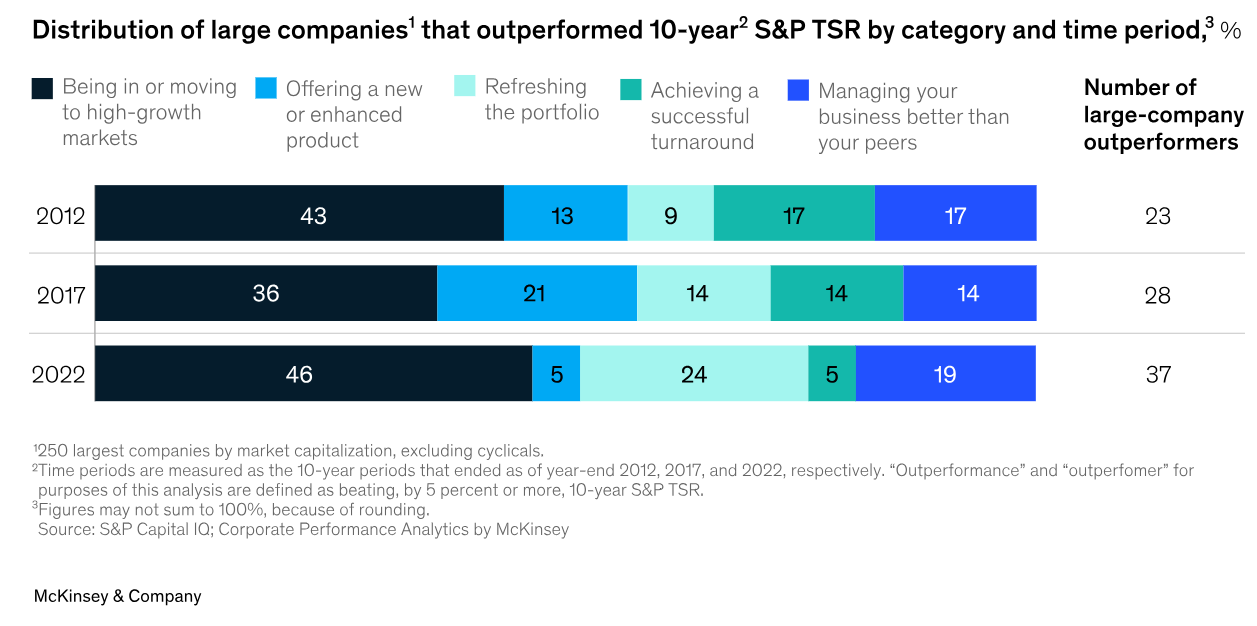

In terms of the top decile performers, only 11%, 15% and 18% in the 10-year period to 2012, 2017 and 2022 respectively, were very large companies (within the 250 largest US publicly listed companies). Surprised by this result, the McKinsey team repeated the exercise, requiring only 5% above the market TSR over the 10 years. Very few of the 250 largest publicly traded companies in the US reached this lower mark: 23, 28 and 37 companies out of the 250 met the grade.

For the report authors, Pedro Catarino, Tim Koller, Rosen Kotsev, and Zane Williams, the implications the first lesson is clear: it’s about setting expectations. Senior executives promising to beat market TSR by 10% or more are unlikely to attain it. They explain why.

“There’s a limit, after all, to how much market size a company can ultimately capture, and smaller companies have a lot more room left to grow. When the market or segment in which a company competes isn’t growing, smaller companies have much better odds of long-term TSR outperformance: the smaller a company’s initial market share, the greater the likelihood that it can beat and keep beating investor expectations.”

The 5 paths to TSR outperformance

The authors believe the widest path to TSR is achieved by being in, or moving to, high-growth markets. Typically they did this by not only continuing to execute well in their core business but investing in innovation and improving processes. They sought out a high-growth ‘niche within the niche’.

“For example, while the pharmaceutical sector has generated strong returns for decades, pharmaceutical suppliers have recently been a growth dynamo within the broader life sciences industry.” the authors noted

For some other large companies, the path to TSR was via a small number of specific products, rather than one business being uplifted via industry-wide trends. Biotechnology companies or pharmaceutical companies are prime examples of this path. The authors note

“Several companies in these industries introduced breakthrough medicines (for example, for autoimmune diseases or diabetes) for which there were large, eager markets; these new products enabled these large corporations to meaningfully beat broader market TSR.”

Refresh the portfolio of businesses within the company and go for value-adding businesses that do not stray too far from the core business is the third path. Companies in this category proactively seek out faster-growing markets where they can build, or practicably acquire, a competitive advantage. This is the narrow path to TSR, with only 9 of the 250 largest companies were able to beat market TSR by 5% or more. However, the authors caution this strategy wasn't for everyone

“Having a proven track record in a core business or businesses was typically a precondition to successfully expanding into new spaces and capturing new pockets of growth," they said.

Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT) is one example of companies following this path.

Turnarounds were rarely a successful path to TSR, with fewer than 20% of performers in the ten years to 2012 and 2017, and less than 5% of companies in the 10 years to 2022 were able to beat market TSR by 5%. While the companies came from a diverse range of industries, large ROIC improvements were achieved through an extensive turnaround process aimed at improving core operations, via efficiency upgrades and economies of scale. The example given by the authors is Best Buy (NYSE: BBY).

The final path to TSR? Manage your business better than your peers. This was a strategy used by companies in a traditional, “steady state” industry. The examples they cite are Costco Wholesale Corporation (NASDAQ: COST) and the US insurer Progressive Corp (NYSE: PGR).

Which pathways proved more popular?

The chart below shows the distribution of TSR outperformers over each of the 10-year periods and the path they deployed.

Across each of these periods, 'being in or moving to high-growth' markets was the most successful path, while the least successful strategies were typically either refreshing the portfolio or achieving a successful turnaround. Note the low number of companies able to rely on new or enhanced products to achieve TSR outperformance.

Taking these insights to the Australian context

I've long been a sceptic about the benefits of a turnaround, so I wasn't surprised to see the research findings on that. I'm curious about the other paths though, and this is where you come in.

Take the top performing Australian stock in your portfolio and let us know in the comments what the stock is, over what period you've held it, what the total returns have been (feel free to estimate) and which of the 5 paths to TSR outperformance it has used to get there:

- Being in or move to high growth markets

- Offering a new or enhanced product

- Refreshing the portfolio of businesses

- Achieving a successful turnaround

- Executing better than your peers