Poker, house auctions, and takeovers

Many investors actually don’t realise that the term Blue Chips comes from the game of poker. Some may say ‘duh’, and others may pride themselves on having no knowledge of games of chance.

According to Investopedia: “The term “blue chip” comes from the game of poker, where blue chips are the highest value pieces. Blue chip companies are stable, profitable companies that are seen as safe investments in their industries. A company must be well-known, well-established, and well-capitalized to be a blue chip.”

Some pretty vague terms in there! Whatever the rubbery definition of a blue chip is, one thing that rings as true today as it did 150 years ago is that managing a portfolio of investments is very much like the game, or sport, of poker.

Not because you are betting on knowns and unknowns, but because the path to success is all about variable betting, or to put it into investment jargon, position sizing (including positions of 0%, ie not investing).

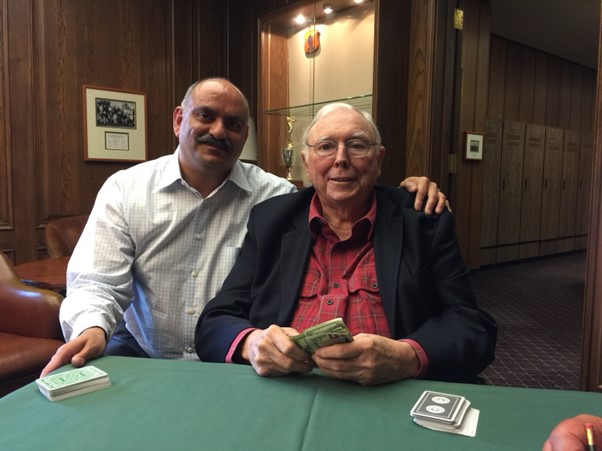

Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway, in college and the Army, developed “an important skill” - card playing.

He used this in his approach to business. “What you have to learn is to fold early when the odds are against you, or if you have a big edge, back it heavily because you don’t get a big edge often. Opportunity comes, but it doesn’t come often, so seize it when it does come.”

Charlie Munger also used the card analogy to explain his approach to investing. He maintained that treating the shares of a company like baseball cards is a losing strategy because it requires one to predict the behaviour of often irrational and emotional human beings (Source: Griffin, Tren (2015). Charlie Munger: The Complete Investor. New York: Columbia University Press.)

The late Charlie Munger always saw the parallels of card strategy and investment strategy.

Charlie Munger’s business partner, Warren Buffet, also puts in 12 hours a week at the bridge table.

If you want to ‘win’ (maybe termed ‘beating the average’) at investing, mastering position sizing is crucial.

Probably the most important factor that has allowed us to beat the equity market indices over 11 years is position sizing (both on a total return and drawdown basis).

However our position sizing is generally quite different to ‘stockpickers’ as we will often increase our position size as a deal plays out and the number of risks, or their magnitude, fall away. This will likely be for increasingly smaller incremental returns (in each deal), but on a portfolio and annualised basis that works very well.

Remember Australian Takeover Laws are a pretty sophisticated part of the Corporations Act. We rely on them.

While Munger did a lot of merger arbitrage at Berkshire Hathway, and even more stock picking, the lesson of position sizing is the same for both styles.

Never Sell or Stop Loss?

Some people laud the never sell strategy. We don't. We are far more interested in stopping loss. We all know Buffett's first and second rules of investing.

As merger arbitrage investors we generally don’t have to make a decision of when to sell. In the vast majority of cases, the takeover occurs, the stock gets delisted and we receive cash for our shares. Decision made for us.

I can’t tell you how much risk that takes off the table. When to sell is a massive variable for most ‘traditional’ Buy and Sell investors. Did I sell too early? Did I sell too late? Should I get back in? This is probably the variable that affects many investors the most.

As I write this I just heard the host on a financial TV channel on in the background say “Stevie said he sold this too early” and the camera shot to the guest presenter mock crying.

While we laugh along, when to sell in 'traditional investing' is hard graft. We don't envy that.

The Liontown Poker Game of 2023 – One where we did make the ‘get out of Dodge’ call

When Liontown (ASX: LTR) initially came into play in the first quarter of 2023, via a conditional takeover bid, we bought a small position based on the risks in the offer.

Then some interesting trading started occurring.

The stock traded to the bid price of $3.00 and it became pretty clear that Gina (Reinhart) was buying a lot of stock. Somewhat counterintuitively, we sold. I’ll tell you why.

We’ve seen other situations where Gina, and for example Chris Ellison from Mineral Resources, buy stock and they are not buying stock to bid themselves, they are buying stock to block.

Experience is what makes the difference. As Luke Cummings, Harvest Lane's CIO, said recently on a podcast "When there’s a bid at $3.00 and you see someone buying a lot of stock, once upon a time my first reaction would have been ‘this is great, there is another bid coming’".

“With less experience in the Liontown situation I could easily have thought that all that buying was going to lead to a counterbid, when in fact not only did it not lead to a counterbid it actually led to the deal breaking and a pretty big cap raising at a discount”.

“A lot of the dark arts of Merger Arbitrage is people tell you what they want you to hear, or they tell you nothing at all. It’s not normal to have to do analysis on people as opposed to the transaction itself, however some other transactions we’d been in previously told us that Gina probably wasn’t going to bid, at least straight away."

“Any arb funds that were in that trade expecting that there was going to be a counterbid from Gina, or anyone else, obviously lost a lot of money through that process”.

The downside in that transaction, and its avoidance, is a big part of our edge.

While we do make the majority of our money in multiple bid situations, what has allowed us to beat the indices consistently over 11 years is avoiding situations where you’d think it was a ‘lay down misere’ that a competing bid was coming; but instead it goes the other way and you land in hot water with steep capital losses like the Liontown example.

As said, we sold out at $3.00 and the cap raising that came in October 2023 was at $1.80 (stock now at $0.88 as an aside). Ouch.

You’ll blow yourself up if you just buy all of these deals when they are announced and you don’t actively manage and don’t adjust your position sizes. The key is to avoid the losses and the blow-ups.

It’s just like poker, it’s bankroll management. There are some hands you’ll never play because the cards are rubbish, there are some hands where for the right value you’ll play and there are other hands where the odds are massively in your favour.

But, but, but as Luke Cummings says “in stock markets, like poker, weird things can happen, and sometimes you can think you are on a sure thing and you are not. So we are ultra focused (Luke often uses the word ‘manic’ – which I think is appropriate) on making sure everything is positioned sized accordingly - no matter how confident we are.

So if something unexpected does happen it hurts a little bit and we lose a couple of percent of the NTA of the portfolio on a deal. That happens a couple of times a year and it has done for 11 years. What you don’t want to do is be so invested in something that if it goes wrong it wipes out your capital.

No matter who you invest with or who advises you (or if you are self-advised) make sure the first question you ask is ‘show me your history of position sizing and explain the size, and it’s variability, to me’.

The Great Australian Feeding Frenzy – the House Auction. Can you invest in it?

Americans think we Australians are downright crazy when it comes to how we transact houses. They think auctions are for paintings and storage shed contents.

Everyone knows, everything apparently, about residential housing as an investment. What most people are happy to ignore is the fact that it is very capital intensive, it is very labour intensive, you’ve generally only got one income source (which can dry up completely for periods of time) and the tax man is increasing looking at you for more revenue.

Imagine instead you could go to house auctions on the weekend and put down an investment that gives you the right to the percentage difference between the first auction bid and the winning bid. In the stock market you can do that – when a takeover is on. And you can do it in an educated and protected-by-law, way.

To somewhat oversimplify what we do, is we buy takeover targets that have a bid at $1.00 (to keep the maths simple), and we buy the stock at 96c. The bids are most often from one of the target company’s competitors, with private equity the second most common bidder type.

Now we expect to receive that $1.00. That doesn’t sound very interesting, but if you do that often enough, in what are pretty low risk scenarios, that works just fine.

Ideally what happens, that $1.00 bid gets improved to $1.10, or $1.20 or $1.50.

It’s like an auction for a house, you turn up on the day, you don’t know who’s going to come and the first bid is very rarely the last or only bid. Like houses it comes down who else wants to own it, how much can they afford and how keen are they.

make sure the losers are paper cuts not a loss of limb

Everyone wants to ‘win’ at investing.

Capital is hard to make, no one wants to whittle it.

If you position size right, you can generate higher returns than the average and protect your capital at the same time.

5 topics

1 stock mentioned

1 contributor mentioned