Policy choices and Australia’s growth conundrum

Economists build their forecasts via the inputs to demand. But when population and productivity are moving this fast, a different approach is needed. In this latest note, Tim Toohey, Head of Macro and Strategy, looks at how net migration, the NDIS and infrastructure boom have juiced the Australian labour market. Given the outlook for all three, he lowers his 2025 economic growth forecasts.

Forecasting the 2024-25 via the population prism

In the dark arts of economic forecasting, economists typically start the process by forecasting the expenditure components of the economy, consumption, housing investment, business investment, government demand and net trade. Most forecasters spend their time focused on the impact that interest rates, tax policies, lumpy investment projects, external demand factors and exchange rates might have in shifting the path of aggregate demand. Population growth, which typically deviated only modestly around its historical average outside of the pandemic and major recessions, was typically a second order focus. Not anymore. In 2024-25 it takes central stage, and it threatens to upend forecasts for economic recovery.

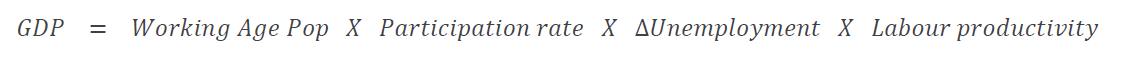

Deep down every economist knows that economic growth can only be achieved via population growth and productivity growth. Predicting productivity growth with any reasonable degree of accuracy is typically a tough task. However, currently we have both population growth and productivity growth jumping around wildly relative to history, so it is important to think through the implications for future economic growth. To obtain a clearer picture of the way that net migration feeds through to aggregate demand growth, consider the following set of identities.

We start with the general condition that economic growth equals employment growth and productivity growth.

Which can be re-written as labour force growth multiplied by the employment rate of the labour force times labour productivity growth.

Growth in the labour force can be defined as the working age population multiplied by the participation rate, enabling the identity to be rewritten.

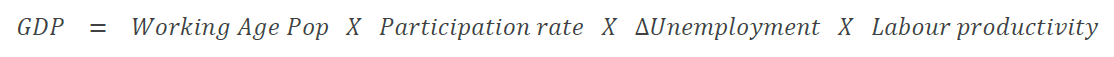

Finally, we arrive at a more useful identity that is more intuitive and valuable for thinking about the economic growth challenges ahead.

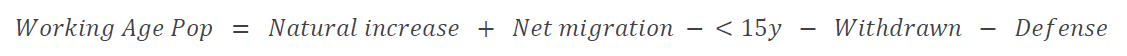

Where the working age population is defined as natural increase plus net migration less those under 15 years, retired, those withdrawn from the workforce and defence force personnel.

Assuming that migrant productivity is no different to non-migrant productivity and that shifts in net migration do not to alter the decision by non-migrant workers to enter or withdraw from the workforce, then economic growth can only grow in direct proportion to population growth and labour productivity. In practice, there are likely delays in getting migrant productivity to be equal to non-migrant productivity due to on-the-job training requirements. Given the high concentration of skilled migrants in prime working age cohorts, it’s reasonable to assume that, over time, migrant productivity would be higher than non-migrant productivity. Nevertheless, this training gap is likely one of the reasons behind Australia’s poor productivity outcomes over the past few years.

Putting net migration briefly to one side, it is also worth thinking about the other forces affecting working age population growth. Australia’s fertility rate fell to 1.63 babies per woman in 2022 – the lowest on record – and based on available data it likely fell to 1.51 in 2023. The 20% decline in fertility in just 10 years is clearly an alarming statistic, with high costs in living, housing, education and low job security all relevant factors. Studies suggesting a marked decline in young people identifying as heterosexual(1) are additional considerations which may have long-term implications for population growth.

At the other end of the spectrum, while death rates rose slightly in recent years due to COVID, the death rate of working age people remains stable. It is likely that the advancements in medical treatments that have supported improvements in longevity skew heavily to cohorts that are already in the retirement phase, and as such, there is only modest benefit to the size of the working age population. In other words, there is little prospect that natural increase in the population can offset any material decline in immigration in the period ahead.

Clearly, Australia needs immigration if it wants to grow the economy. This statement has been true since 1976, when the fertility rate fell below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per couple. In the face of a precipitous decline in fertility it’s even more relevant now.

How much is too much immigration?

When net migration is done in excess over a short period of time, the living standards of the local population will be challenged. Congestion, strains on government services, the drawing forward of expensive infrastructure upgrades and, of course, the exacerbation of housing shortages are all real and apparent negative externalities. Some of these issues are of course worsened when the mix of skilled migrants is not skewed towards the sectors with the greatest skill shortages. The question is how much immigration is too much?

One way to answer this question is via analysing the impact on the labour market. We know from the third identity on page one that the determinants of population growth and shifts in the unemployment rate and labour force participation are all crucial in determining the pace of economic growth. However, what economists rarely think to show is the decomposition of employment growth via these key determinants. i.e. from the perspective of net migration and the natural increase.

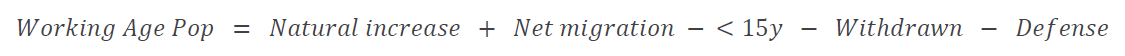

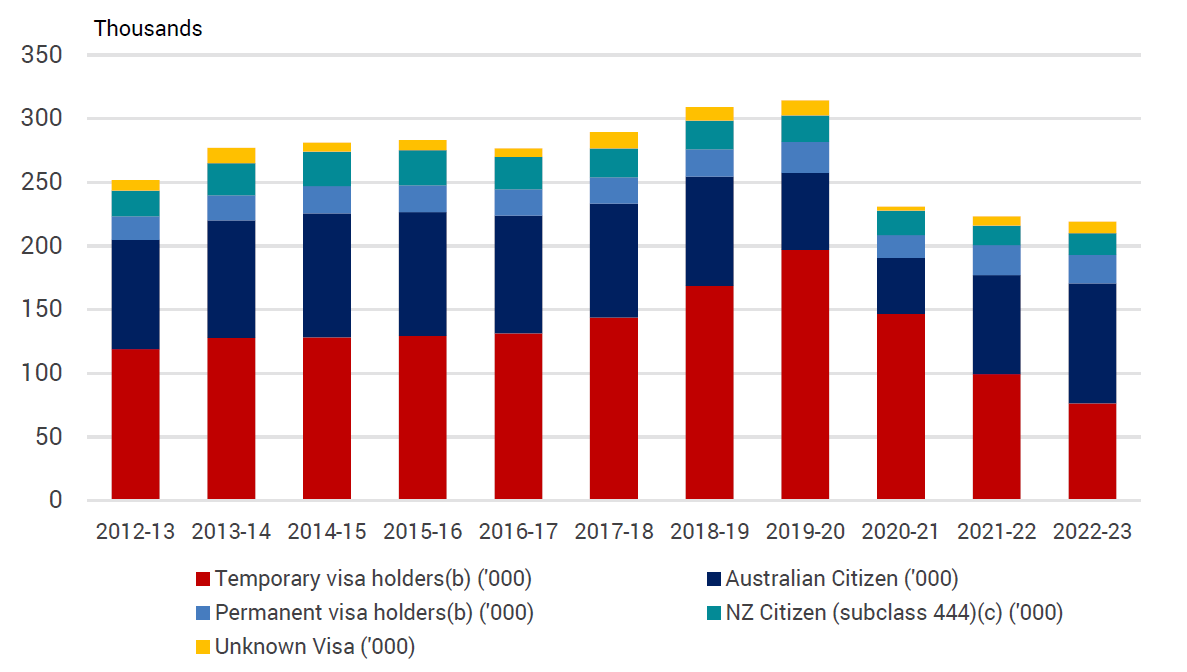

Exhibit 1 – A Decomposition of Australia's Employment Growth

Source: ABS, YarraCM

Exhibit 1 shows that a particularly interesting dynamic has emerged in recent quarters. Employment growth remains strong, yet since the start of 2023 the non-migrant population has started to progressively withdraw its participation from the workforce. Since mid-2023 a new phase commenced, whereby the strength in net migration was more than sufficient to supplant non-migrant workers in the workplace, generating a trend rise in the unemployment rate. In other words, net migration is currently supplying 1.4 people for every new job created!

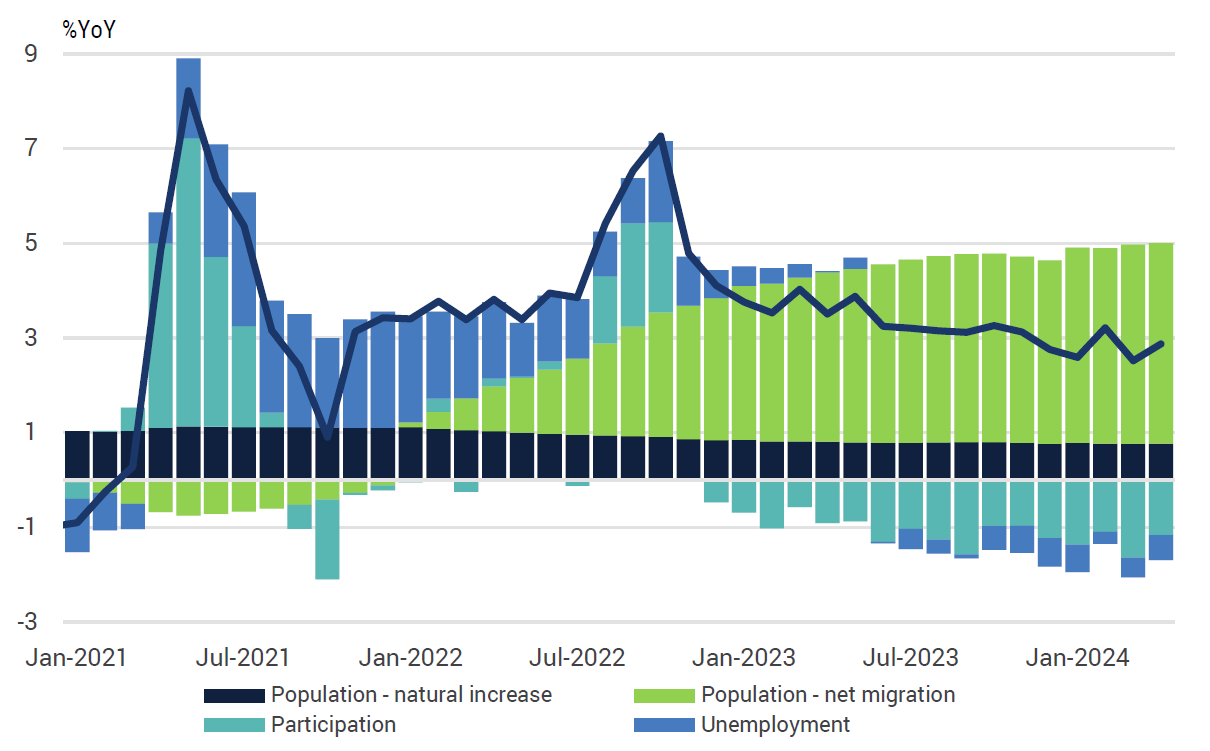

This is a highly unusual scenario. To illustrate just how strange, consider how employment growth would have looked through time if we extract net migration from the workforce (Exhibit 2). Typically, employment growth excluding net migration moves in sync with total employment growth, except in periods where economic growth is well above trend and the resulting labour shortages are filled via immigration. Currently, excluding the COVID period, the gap between the two measures has never been higher. In the absence of net migration, employment growth across the non-migrant workforce is currently essentially zero.

Exhibit 2 – Employment growth excluding the net migration impact

Source: ABS, YarraCM

At this point, it is important to stress that the common assumption is that the causality is typically assumed to run from strong expected economic growth to strong employment demand to rising demand for skilled net migrants to fill the available roles. That’s a pretty reasonable assumption in normal times and it forms the basis of the RBA’s rationale that immigration adds to both demand in the economy and supply to factors of production.

However, the current environment is far from normal. The policy objective, after strong business lobbying, was to recapture the shortfall in immigration during the COVID period by running well above average immigration with a focus on students and filling roles in the hospitality and accommodation sectors that non-migrant workers had increasingly shun. Hence, in this catch-up period new migrants found employment relatively easily and hence the supply of labour to the economy was met with a comparable lift in aggregate demand.

Relative to the pre-COVID trend for net migration, it appears that the catch-up period is now complete. Falling job vacancies also suggest the pent-up demand for labour is now becoming satiated. Unless non-migrant employment growth and total employment growth moves back into balance, we believe there is a far greater risk of a larger rise in the stock of unemployed and that the prior gains in lifting workforce participation will reverse. In an election year this could be particularly painful for the incumbent government.

Turning the tap? Be careful of unintended consequences.

But both sides of government are planning relatively modest cuts to migration, right? Yes and no. There is a big difference between the immigration target provided by the Total Migration Program as outlined in the Budget Papers and net overseas migration (NOM). The latter includes both permanent and temporary migrants (including students), as well as Australians entering and leaving the country. It counts people who stay in Australia for 12 months (or more) over a 16-month period. The Migration Program, on the other hand, sets the number of permanent visas to be granted across Skill, Family and Special Eligibility categories. Many people granted visas under the Migration Program are already in Australia at the time of visa grant and have already been counted in NOM figures.

To put it in context, the target for the Migration Program in 2022-23 was 195,004 places, the NOM outcome was 2.8-times higher at 538,000. The target for the Migration Program in 2023-24 was 190,000 places, the NOM outcome for the first six months is already 258,000 and will likely exceed 450,000 when the data for the full year becomes available. The ALP’s Migration Program target for 2024-25 is 185,000, and this compares to the Coalition’s announced plan to cut the target to 140,000 for both the 2024-25 and 2025-26 years.

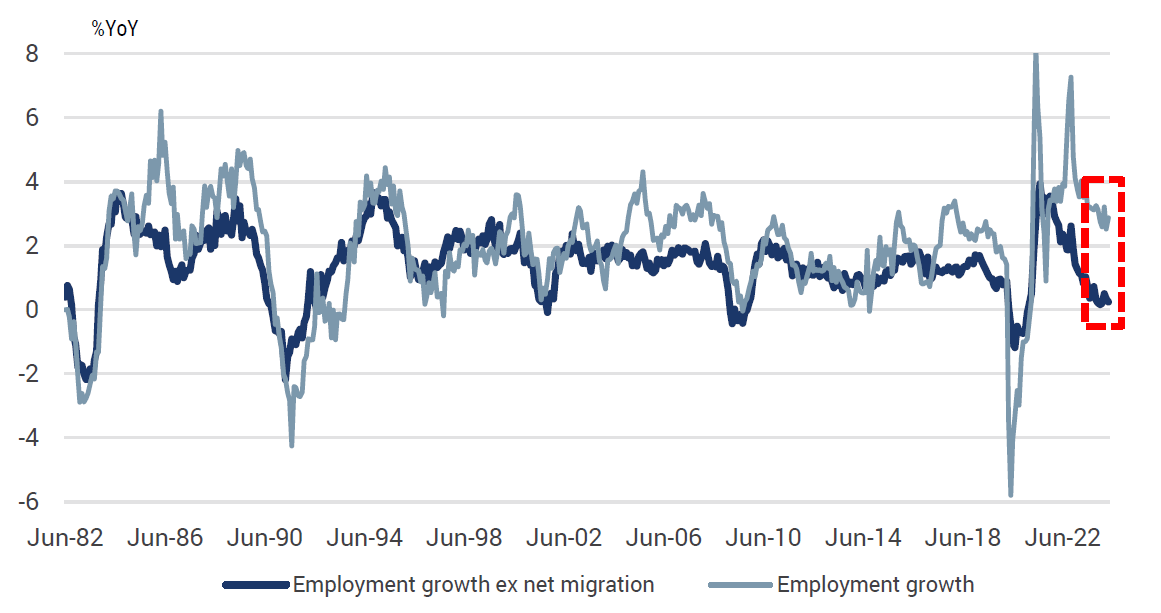

Exhibit 3 – Overseas migrant arrivals: visa and citizenship groups

Source: ABS

Exhibit 4 – Overseas migrant departures: visa and citizenship groups

Source: ABS

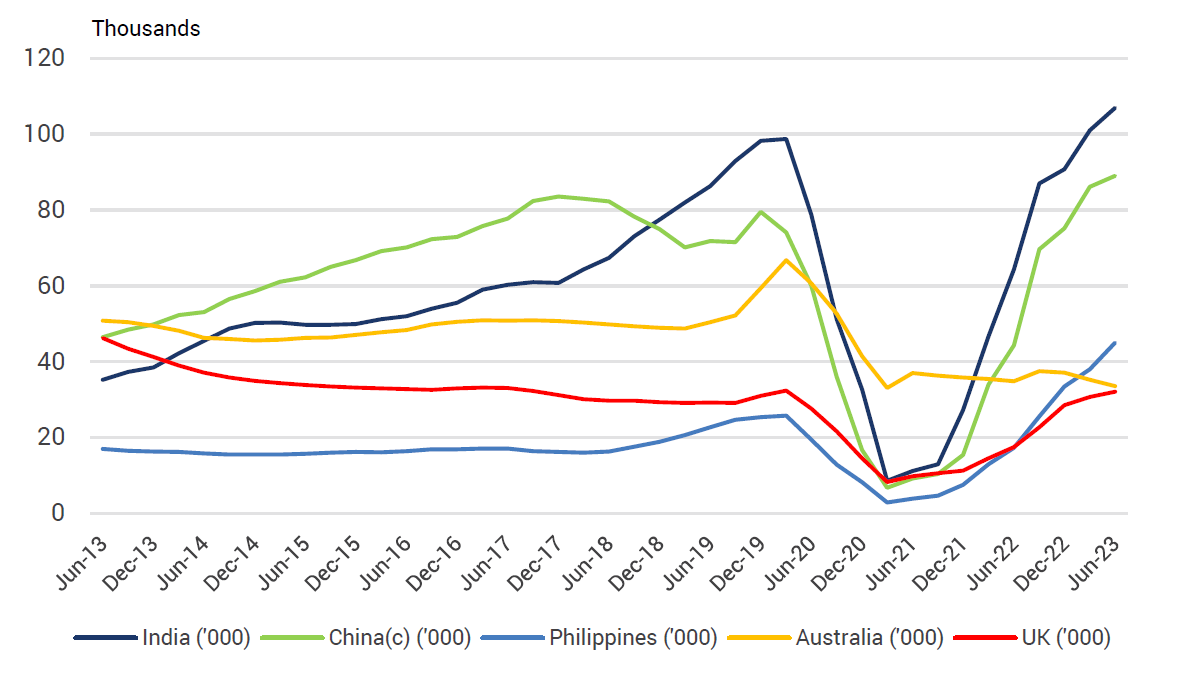

Exhibit 5 – Overseas migrant arrivals: top 5 countries of birth

Source: ABS

The Coalition’s plans are more restrictive, but the reality is that it’s not the shifts in the Migration Program target that matter, it’s the movements of temporary visa holders that matter far more. As Exhibits 3 and 4 show, it’s the surge in temporary visa arrivals and slowdown in temporary visa departures that have driven the population surge. China, India, Philippines, Nepal, Pakistan, Brazil and Columbia have all been important contributors to the strength in recent arrivals, all largely student driven. Thus, it is the ALP’s plans to apply soft caps on student numbers for each higher education institution (breaches of the soft cap are to be allowed if the education provider provides new accommodation for the foreign students) that will likely have a far bigger impact of population growth.

Running higher education as an export business always had its flaws. Reform to the sector, including limiting numbers of foreign students, is long overdue. Yet, from an economic forecasting perspective, restricting the level of foreign students will pull the handbrake on Australian population growth. We simply don’t have the policy detail to be able to make an accurate assessment upon future population growth, but we do know that people who arrive on temporary visas in 2022-23 accounted for 75% of arrivals, 54% of which (236,600) were international students.

If Australia caps international student numbers while also reducing the skilled migrant program, then the only source of migrant growth would be temporary skilled migrants and working holiday visas. However, these are relatively small categories.

In short, a 30-40% decline in total arrivals in 2025 could easily occur. It is also worth noting that the fall in temporary visa holder departures in recent years was mostly due to existing students completing their studies post the COVID interruption to new student flow. As a result, we should expect a significant rise in student departures through the remainder of 2024 and 2025 which would only exacerbate the likely future decline in net overseas migration. It is entirely feasible that net migration could more than halve in 2025 and in the process drive population growth from 2.5%yoy currently to ~1%yoy through 2025.

That’s a very big headwind for economic growth. At this point it’s worth referring back to our final GDP identity:

Where:

Rapidly slowing population growth from 2.5% in 2024 to 1% in 2025 presents a reduction in GDP growth of 1.5% relative to current economic growth, all else equal. Given aggregate demand is barely expanding at all currently, that is obviously a concern.

But that is not all that is going on in that economic growth identity in 2024-25. The RBA’s intent is to drive the unemployment rate above its estimated non-accelerating rate of unemployment (NAIRU). Their best guess is that the unemployment rate needs to rise 50bps, which via the identity takes another 0.5% off economic growth. When the unemployment rate rises, typically the participation rate declines as those actively seeking work become discouraged – another hurdle for economic growth to clear in 2025.

The shifting hand of the public sector on future employment growth.

The Government’s hand is also clearly still evident in shaping employment growth via three channels.

The first is the role the government, both federal and state, have played in generating an ongoing infrastructure boom. It should be apparent to all in an environment when private sector demand growth is stagnant that the only way the RBA can continue to assess that the economy is operating above its productive capacity is due to excessive government demand. Unfortunately, the latest set of National Accounts show government demand accelerating at a time when better news on inflation is desperately needed. As such, the odds of a traditional pump-priming pre-election MYEFO later this year are now falling rapidly and with it the support that fiscal stimulus will provide for the employment market.

The second is rampaging spending in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). The NDIS has been expanding at 20% p.a. in each of the past three years. It currently costs $44bn and is projected to rise to $61bn by 2027-28 according to the 2024-25 Federal Budget. This assumes that $14.4bn in savings are made to the scheme over the next four years, which given the recent track record of the NDIS is a heroic assumption. Looking at the trend in the employment sectors that benefit most from NDIS spending prior to and post the 2017-18 period – when NDIS spending began to really ramp up – suggests that a massive 1-in-3 jobs created in Australia in the past 12 months could be attributed to NDIS spending. With evidence of widespread fraud now being made public, the pressure on the government to rein in NDIS expenditure will only increase. If the government is successful in its planned 60% reduction in the pace of annual NDIS spending growth, then a major source of employment growth will be severely contained in 2024-25 and beyond. Indeed, if the Government hits its forecast numbers for the NDIS, we could see employment growth lowered by 0.5% in 2025.

The third relates to the defence force and is a much smaller affair, albeit relevant for the employment statistics. The defence force is excluded from the workforce numbers by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, yet the defence force competes in the same labour pool. The defence force is currently some 8% below its target personnel requirement. Combined with a growing defence budget – a projected 15% rise by 2027-28 – expanding defence force personnel numbers will lower the available civilian workforce, all else equal.

In short, the public sector’s policy choices over recent years have placed them in direct competition for resources with the private sector. Large investments in energy transition, defence, roads, rail, and utilities have collided with the NDIS juggernaut to help pump up employment growth and input costs. Yet, there is evidence that the supportive hand of the public sector to employment growth is now shifting:

- The backlog of government sponsored infrastructure work yet to be completed has now peaked, excluding the electricity and defence sectors.

- Plans to shackle the growth of the NDIS are at least being formed.

- The appetite for further fiscal stimulus is being diminished, with recent inflation data keeping the RBA’s finger poised on the interest rate trigger.

None of this will see the public sector shed labour, but it will moderate the pace of public sector employment growth.

Productivity to the rescue? Yes, but we downgrade economic growth nonetheless

When viewed from the perspective of slowing population growth, the RBA being intent to drive the unemployment rate higher, and restraints on future government spending, it’s clear from the growth identity that the only force that can generate anything other than very modest economic growth in the next year is productivity growth.

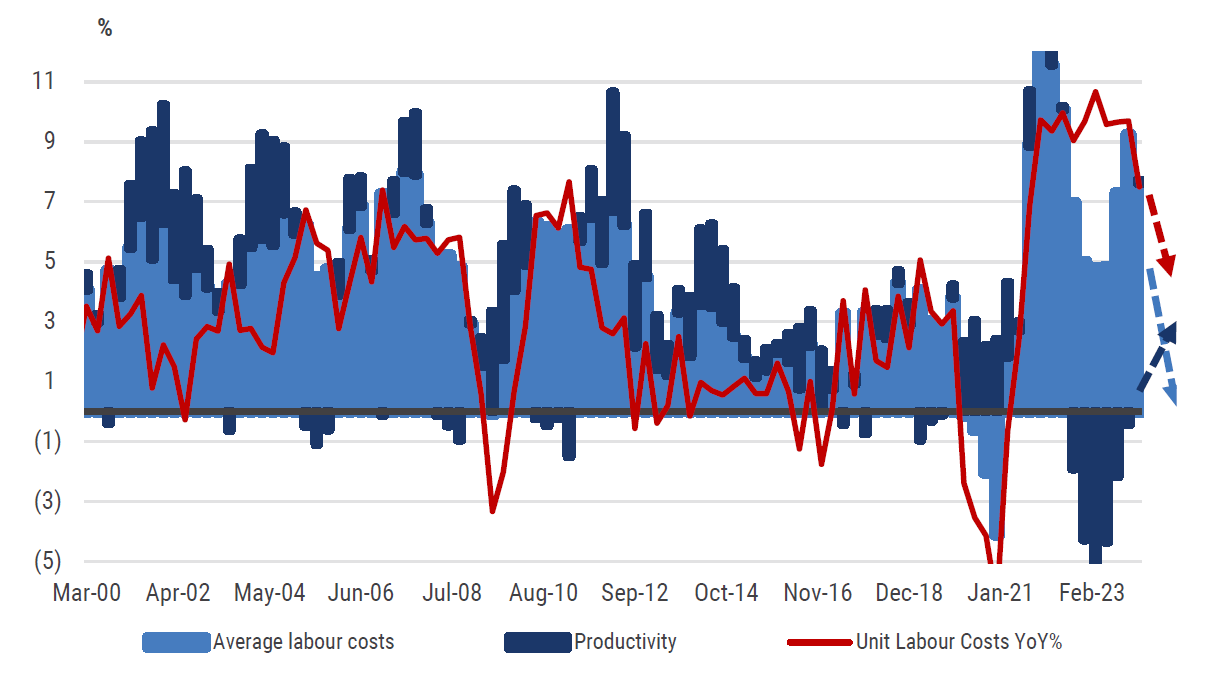

The bad news is that productivity declined 2% p.a. in 2022 and 2023. The slightly better news is that in the year to March productivity eked out a 0.1%yoy gain and six-month annualised growth has risen to 2%. This is important as it is helping to facilitate a slowing in unit labour costs and a better outlook for domestic inflation. It is also very much consistent with what we predicted in our June 2023 note (“RBA’s Shifting Goal Posts Risks a Hard Landing”). Yet we will need to see much more of this type of productivity improvement in coming quarters if economic growth can recover and for inflation pressures to ease. The arrows on Exhibit 6 show our expectations for the aggregate, however, it will also need to extend beyond mining, electricity and professional services sectors and be more broad-based.

Exhibit 6 – Unit Labour Costs Growth and Productivity Growth

Source: YarraCM, ABS.

While we still think productivity growth will continue to rise through 2024 and unit labour costs will slow sharply, this analysis around the drivers of employment growth, the outlook for population growth, and the potential for unintended impacts from government policy leave us more concerned about the prospect for economic recovery in 2025.

We are formally reducing our economic growth forecasts for 2025 from 2.25% to 1.75%. Further interest rate hikes are not warranted in our opinion. However, if the RBA does choose to re-start the hiking process with these dynamics already in chain, then a hard landing for the Australian economy would become increasingly likely.

Learn more

For further insights from the team at Yarra Capital Management, please visit our website.