Post results, updated bank debt issuance and HQLA buying forecasts

Following the banks' latest results, we have updated our estimates of: (1) the quantum of debt they have to issue to replace the $139bn Committed Liquidity Facility and repay the RBA's $188bn Term Funding Facility; and (2) the value of the high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) that they need to buy to reflect both the closure of the CLF and the HQLA that disappears once the TFF is repaid. We also flex this analysis to account for a sharper RBA taper of its bond purchase program and various bank-mitigation strategies.

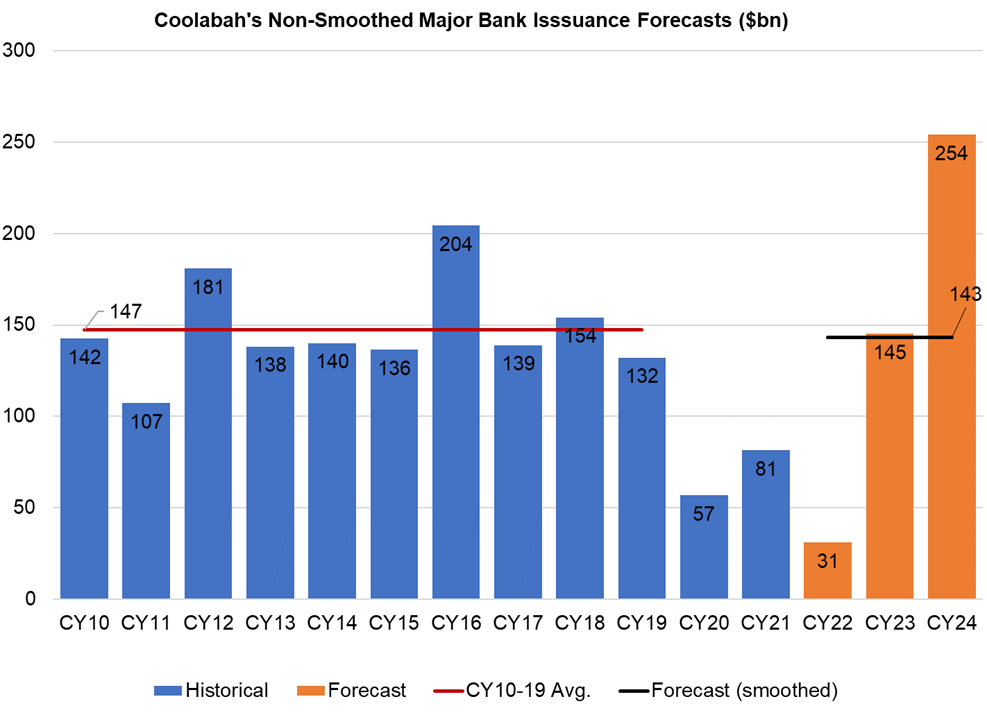

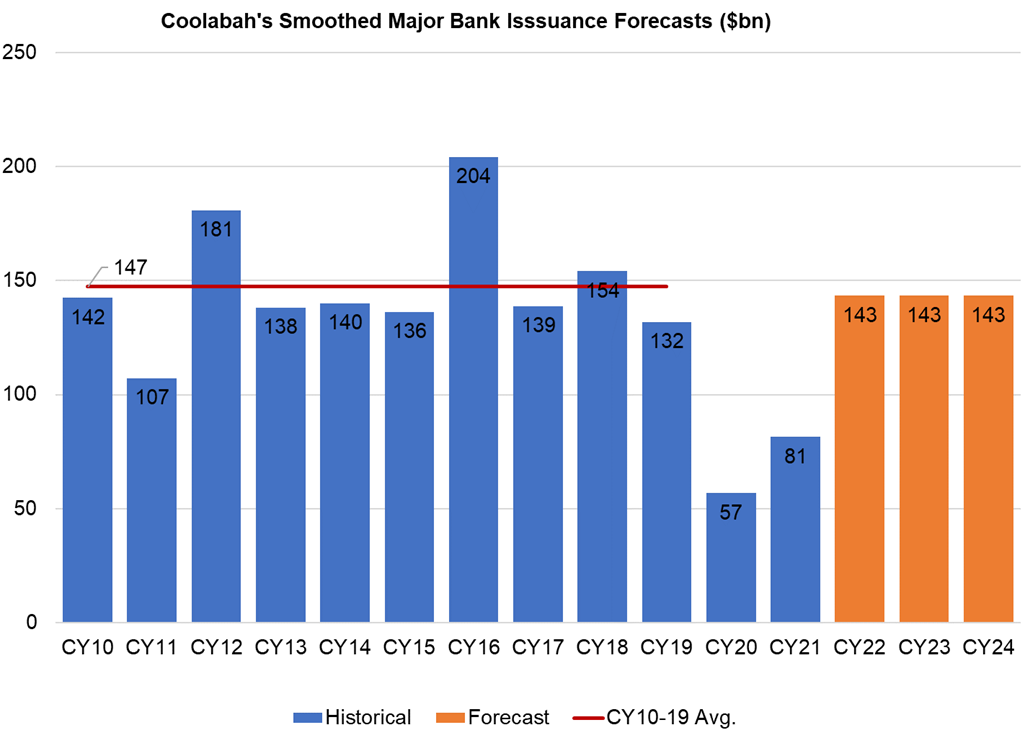

We find that the four major banks currently have to issue about $143bn pa of debt over the next three calendar years, assuming circa 5% pa balance-sheet growth and 4% pa deposit growth. While this is a superficially chunky task, it is actually in line with the $147bn pa average total issuance from the majors over the period CY2010 to CY2019. The required debt issuance ramps-up sharply over the next 3yrs, which we would expect banks to try to smooth. And different banks will have different needs in the short-term: whereas Westpac says FY22 will go back to a typical $30bn to $40bn issuance program, with the risks skewed to the upper-end of that range, ANZ has a lot less to do.

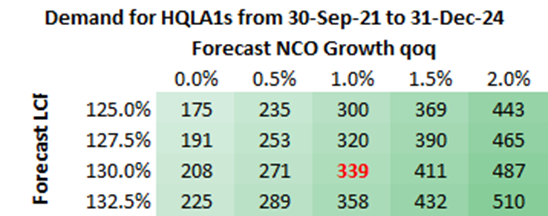

In terms of the HQLA shortage across the banking system, we find that the banks will have to buy about $104bn of HQLA in CY2022 (based on our estimates for their HQLA shortfalls in September 2021). (Note that HQLA includes both government bonds and cash held on deposit with the RBA.) The banks' HQLA buying demand rises to $137bn in CY2023 and then $172bn in CY2024 with a total of $339bn over the period between September 2021 and December 2024.

If for some reason the RBA stops its bond purchase program in February, this forces banks to buy more HQLA in 2022 because the RBA is creating less digital money for the banks to hold as cash on deposit at the RBA, which counts as HQLA. Specifically, going from $4bn/week to zero in February means banks have to buy an extra $22bn of HQLA in 2022 because of reduced excess digital cash in the system.

The same principle applies to the TFF: it created $188bn of additional digital cash, which will disappear when it is repaid. Note that in our analysis below, we have assumed the TFF is repaid on the due dates rather than an head-of-time. In practice, it may be smoothed, which would bring forward further HQLA buying demand for the banking system.

This research assumes that the average Liquidity Coverage Ratio across the banks actually drops a bit from 133% currently to 130% in the future. While some think banks might be able to run lower LCRs, these key liquidity metrics are immensely volatile day-to-day (they can easily drop from 125% to 100% in a day), which is why most bank boards usually target LCRs ranging from 125% to 135% as a reasonable buffer over APRA's 100% minimum.

Since this volatility is not going to go away, it is hard to believe bank boards would have appetite to run substantially lower LCRs. Nonetheless, if we drop the assumed average LCR from 130% to, say, 125%, it does not have a big impact: estimated bond-buying from September 2021 to end 2024 only falls from $339bn to $300bn (see table below).

There are other potential mitigants for what appears to be a large bond-buying task. While most banks believe it is very hard to manage or materially reduce their 30-day Net Cash Outflows that go into calculating their LCRs (which compute the total value of HQLA relative to NCOs), it is possible that NCOs might not track deposit growth over the next 3yrs.

So rather than growing NCOs at the same rate as deposit growth, we can flex our model to assume, say, NCO growth through to December 2024 that is half what one would normally expect due to mitigation measures (ie, a reduction in NCOs versus the normal case where they track deposits). This definitely helps somewhat, reducing the total required bond buying from $331bn to $271bn.

A final interesting exercise is to examine what happened the last time APRA updated the banks' liquidity rules in a manner that resulted in bond buying. In May 2013 APRA first released a discussion paper on moving Aussie banks to the Basel 3 LCR regime that would require them add to lots of HQLA, primarily in the form of government bonds. The LCR regime was officially introduced on 1 January 2015, which is the same year that the CLF was also made available as a substitute for HQLA (the CLF will disappear at the end of 2022).

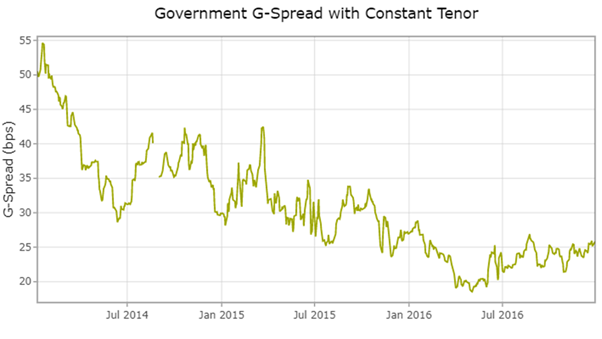

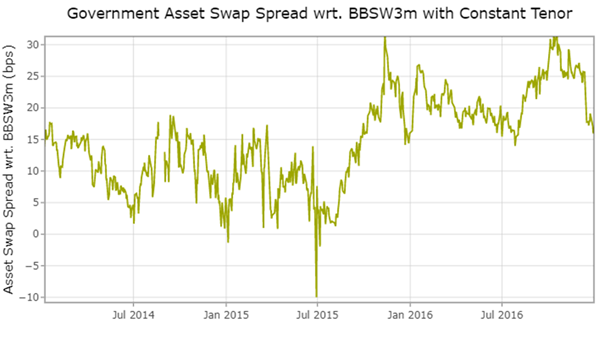

Banks had all of 2014 to prepare to meet APRA's LCR requirements via their bond-buying initiatives. It is easy to see the impact of this on the spreads on different types of HQLA. For this analysis, we focus on 10-year NSW government bond spreads over (1) the Commonwealth government bond yield curve and (2) over the swap rate. The first chart below shows 10yr NSW bond spreads over Commonwealth bonds from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2017. You can see that from January 2014 to January 2015 these NSW spreads to Commonwealth bonds fell by about 20-25bps. They continued falling to about 18bps over Commonwealth bonds by early 2016. The second chart shows the same 10yr, constant maturity NSW bond index as a spread to the 3 month bank bill swap rate. These 10yr NSW spreads to swap are much more volatile, but averaged around 10bps (ranging between 0bps and 20bps). They did not exceed 20bps over swap until 2016.

3 topics