Public vs Private Investing

It’s no mystery why the discussion of public versus private assets has the potential to become such a heated debate: this is an incredibly deep topic, full of nuance and different suitability to different portfolios. To write about it strongly risks ‘boiling the ocean’, and yet here we are.

Whether a client is invested in an industry fund with large allocations to unlisted property or uses a managed account with holdings in private credit, the balancing act between public and private assets does require some measured rationale – and a comprehensive understanding of the applicable risks to either side.

For this note we’d like to explore a single question:

Is there consistent potential for alpha in public markets, and if the alternative is private markets, are investors always adequately compensated for the increased risk?Public Alpha

There is a lot of disagreement in the investment community around whether active management in the public markets can outperform the index – in other words, can managers consistently generate alpha?

(As a sidebar we do not consider outperformance over an index as true alpha, but a conversation about factor investing will blow out the word count of a short note)

A famous example against public market alpha was Warren Buffett’s bet with the hedge fund industry – he argued that a hand-picked basket of hedge funds, after fees and costs, could not outperform the S&P 500 over 10 years. He won the bet, and this example has been rolled out by many “finfluencers” to a young generation of investors to entice them into buying a course where they teach you to invest in index funds.

This more or less falls to the idea that markets are efficient, which would imply in the long run the index will always outperform.

The efficient market hypothesis is another one of those ‘heated debate’ areas, and where we prefer to play somewhere in the middle: assume markets are generally efficient and then consider areas where you might have an edge, in our case in multi-asset portfolio construction.

For example, to find an edge you might ask “has the rise of passive investing and subsequent indiscriminate capital flows made markets less efficient?”.

A paper released last year by UCLA professor Valentin Haddad had some illuminating evidence to answer that exact question. Hadad et al found that in the US stock market, the rise in passive investing over the past two decades had led to a reduction in ‘competition’ of 15% in markets – basically, markets had become less efficient and less competitive, as less aggressive index strategies began to take market share from stock pickers, leaving room for some outperformance by capable investors.

This view largely aligns with our own, that certain factors drive most movements in markets, but there are opportunities to outperform through robust portfolio construction – and this means relying on multiple asset classes and mixes of managers.

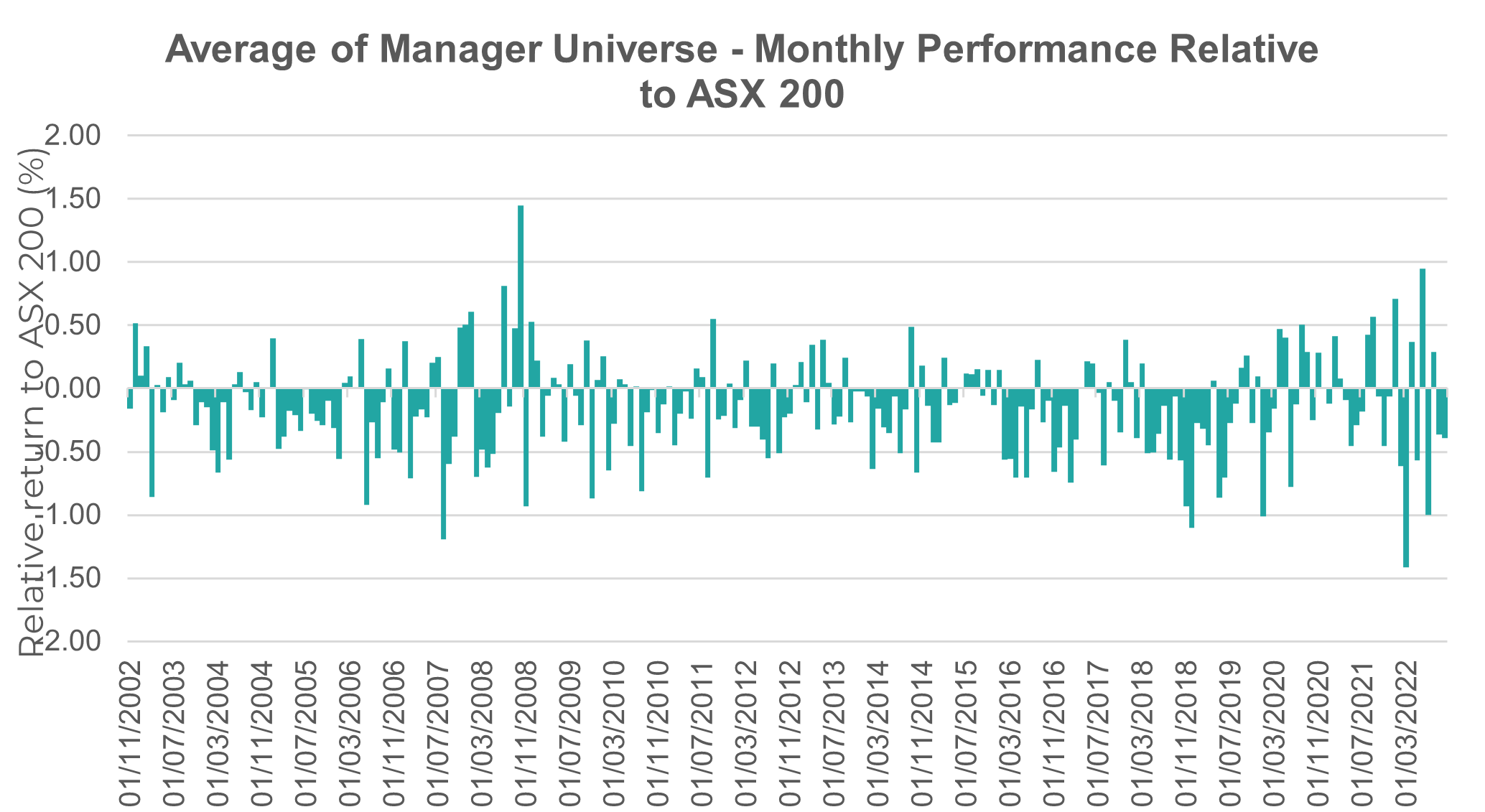

To add some credence to our own views, we extracted the performance of 480 strategies classified as Aussie Large Cap Equities from Morningstar and tracked their performance back to 2002 (or from inception, if they did not have a 20-year track record). We then compared their monthly performance to the total return of the ASX 200.

On average, this universe of managers underperforms the index by -0.15% on a monthly basis.

The

average out/underperformance has cyclical properties (see the chart below),

supporting evidence in our analysis over the years that manager performance

tends to mean revert over time.

There is meaningful dispersion between top-performing and bottom-performing managers consistently over time. Over the past 20 years, the average difference between the top 10 and bottom 10 Aussie large-cap managers has been 5.69% on a monthly basis.

The challenge is – can you correctly identify those top 10 managers from a universe of nearly 500?

Given that our view for over a decade has been that asset allocation and portfolio construction is 90% of investment management, we’d posit that most cannot pick who will be consistently in the top 10 for 20 years.

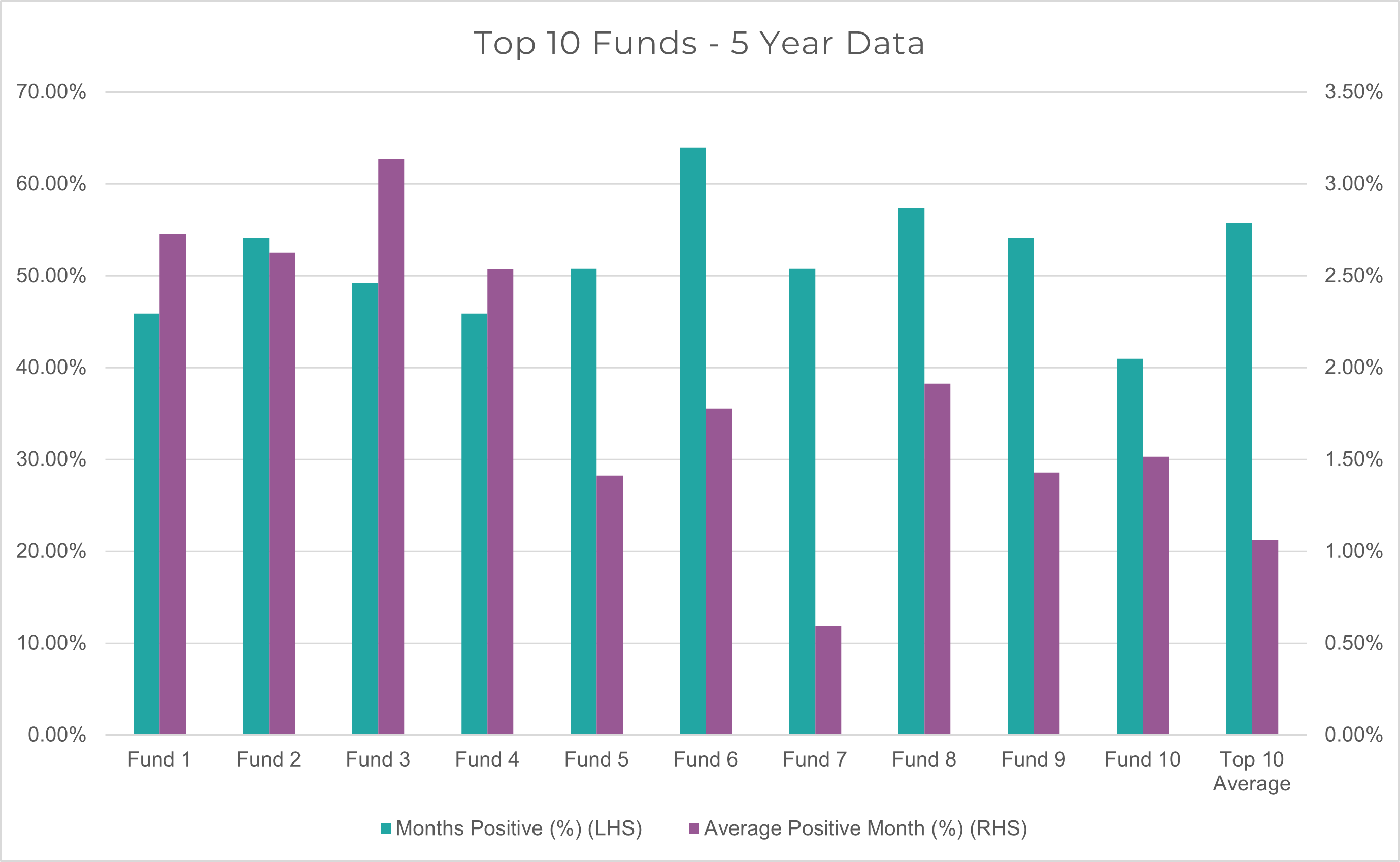

To add another layer of uncertainty, let’s take the top 10 performing funds over the past 5 years, and scrutinize their monthly performance – are the top 10 performing active managers consistently in front of the benchmark? Perhaps surprisingly, the answer is no.

Granted this may not look like it's unfavourable – but keep in mind this is the top 2% of all Aussie managers over the past 5 years, and the average is just above a coin flip if there is outperformance over the ASX 200.

Moreover, on average, the longest period of underperforming the benchmark was 7 months. That means you could identify a manager who has performed well historically, put your clients into such strategies, and conceivably see half a year of underperformance. That is not to say the strategies may not outperform sometime in the future, however, it does show that eschewing a dynamic process in favour of chasing one source of ‘alpha’ is fraught with perils.

So, whilst there are conflicting views on if certain market dynamics, like the rise of passive investing, have impacted manager ability to create alpha, the data certainly shows that investors should take a robust approach to select managers rather than backing one strategy with the hope that they’ll remain front of the pack over your entire investment horizon.

Private Risks

Does this imply that your entire portfolio should switch over to private markets, where inefficiencies and more specialised strategies may have an advantage in generating alpha?

As with all things, investors need to weigh up the risks of any asset. This means you should always consider the risk premium you are receiving over just holding cash.

Of course one of the largest risks faced with private markets is illiquidity – for most investors, it is wholly inappropriate to have their entire investment portfolio inaccessible for 7-10 years, particularly when employing a financial advice service.

The private market has many strategies available to investors and their advisors, ranging from quarterly liquid to multi-year lockups, but in general private markets will have some form of illiquidity present.

To know if you’re being adequately compensated for illiquidity, you also need to consider the underlying valuation of assets.

Unlisted, infrequently marked assets are a risk in the sense that these valuations can be “stale” – public markets are the harshest and most expedient judges in the world, and an investor will be fully aware of exactly what their assets are worth at any minute of market open hours. On the other hand, if your unlisted property holding hasn’t updated pricing in six months and you know that public equities have dropped 20%, are you truly confident saying your investment is “low volatility” or simply that you haven’t received your latest scores from the judges yet?

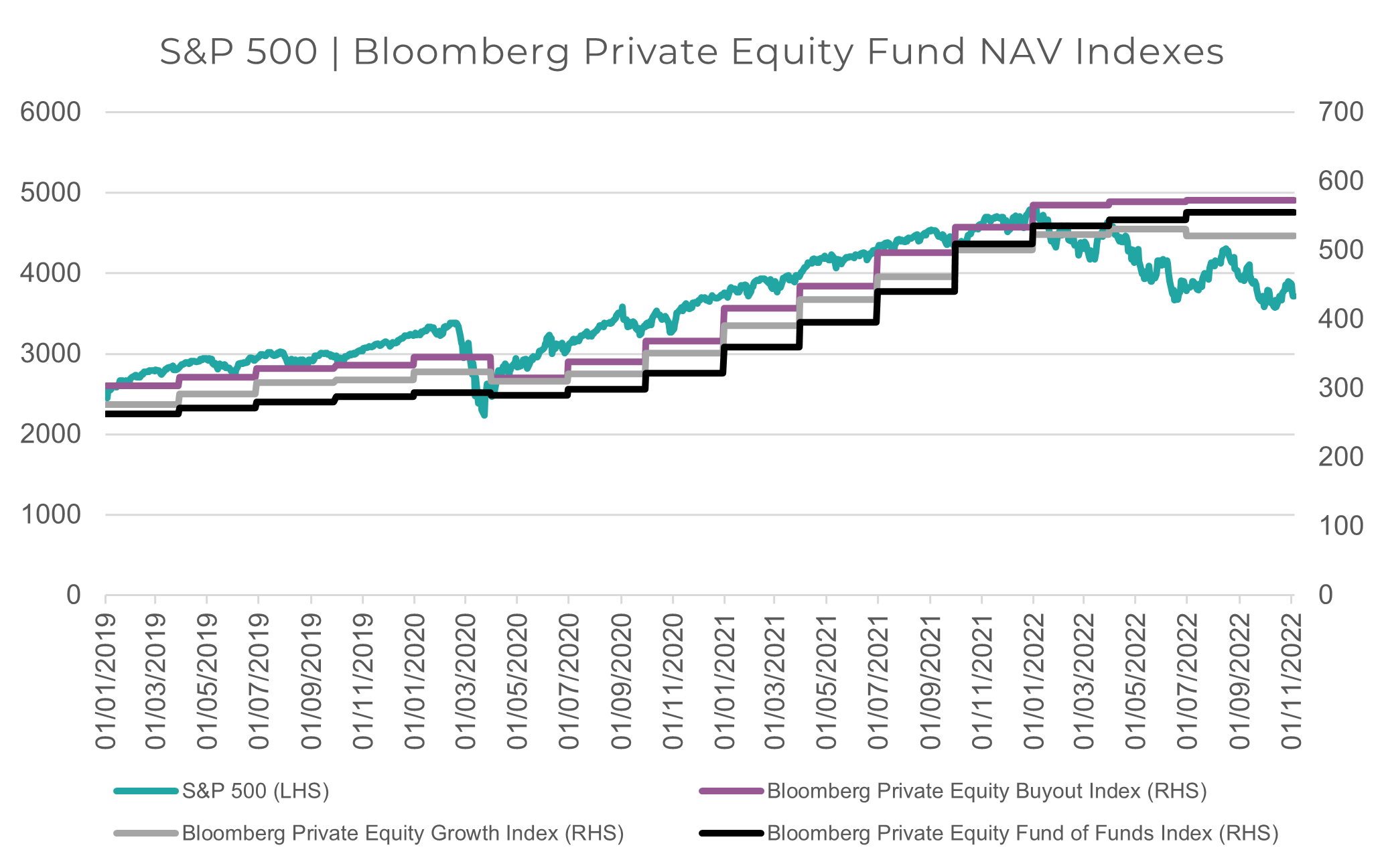

To use an extreme example of comparing the S&P 500 against the various Bloomberg Private Equity Fund benchmarks, the effect of infrequent pricing is quite evident in this recent market sell-off: it seems unlikely that three PE indexes, which have remained flat during this entire bear market, are accurately reflecting the reality of the underlying assets.

Do these two risks mean you can never allocate to illiquid private markets of any description? Not at all.

Those strategies defined as illiquid should offer dramatically different return profiles, often sourcing returns from uncorrelated sources to public markets – and often over strategic time horizons these strategies do produce returns in excess of public market strategies. An assumption here, of course, is that a client’s time horizon and your portfolio construction process allow for (and see potential value in) the illiquidity inherent in these investments.

Any investment manager allocating in a robust framework should consider alternative strategies and the relative merit they might bring at any point in time. – for example during a time when stocks and bonds were both moving in the same direction, seeking alternative exposures offered a healthy dose of diversification and an uncorrelated source of returns from the ubiquitous selloff in public markets.

We’ll touch on a question again: are private assets seemingly holding high valuations despite a dramatic public sell-off or deteriorating macro conditions?

In our view this is a key risk to consider when seeking ‘private premium’; if unmarked assets are still flat (or positive, in some cases) despite public assets selling off aggressively, best case scenario these valuations remain stagnant and don’t participate in any upside from a future economic recovery, worst case they finally get marked down and an investor “bought at the highs”.

If stale valuations are present, then perhaps an investor wouldn’t allocate at that time.

But to throw away an entire investment universe from your process entirely, particularly one that can complement public assets (or even add alpha during times when indexes are more likely to outperform active), limits your opportunities to provide better outcomes to your clients.

Astute investors recognise opportunities for different sources of returns come with certain idiosyncratic risks, but the presence of risk should not necessarily limit your remit, only make you aware of how to manage that risk and how this conflicts or complements with other assets you hold.

Concluding with an author’s aside

Please indulge an analogy, brought to you in first-person narration. When I was growing up, I would often watch my grandfather – like many European grandparents, a talented and pragmatic builder – working on various projects around the property. Being a bricklayer by trade, I would keenly observe him splitting those old 1940s red bricks into various shapes and sizes, as clean and easy as if he was just slicing warm butter with a sharp knife.

I remember watching him use a hammer and chisel, wondering why he was making things so complicated and hitting one tool with another. Surely just split it with the hammer? (Hammers are the favourite smacking instrument of a 5-year-old apparently)

So of course, off in my own corner of the workshop, I tried to crack a brick-like nonno, with only my hammer. The brick was unimpressed and I probably cracked my thumb once or twice in the failed attempt to take the ‘easy way’. One of the many, many lessons I learned from my grandfather was this: when you have a job to do, take no shortcuts, use the right tools and don’t be fooled by the most “simple” solution.

We would encourage any investor to take this lesson to heart, don’t look for the shortcut in selecting assets for your portfolio. Be robust, be mindful of risks and importantly consider what will best serve yourself and your clients over a meaningful time horizon.

5 topics