QE 2.0 is coming: do you know why?

In this new paper, Coolabah's Chief Macro Strategist, Kieran Davies, and its Chief Investment Officer, Christopher Joye, examine the case for the RBA launching QE 2.0 after the current $100 billion QE program, which has helped slow the ascent of both long-term interest rates and Australia’s trade-weighted exchange rate, expires. They focus, in particular, on the challenges the RBA faces trying to stoke incredibly weak wages growth at a time when the labour market is a long way from being fully employed, the RBA's other monetary policy tools appear to have exhausted their available stimulus, and fiscal policy is about to start detracting from growth as the government’s spending programs unwind. Martin Place's policy decision-making is being further complicated by lockdowns and double-dip recessions overseas, and the spectre of a one-sided trade war with Australia’s largest export partner.

Summary

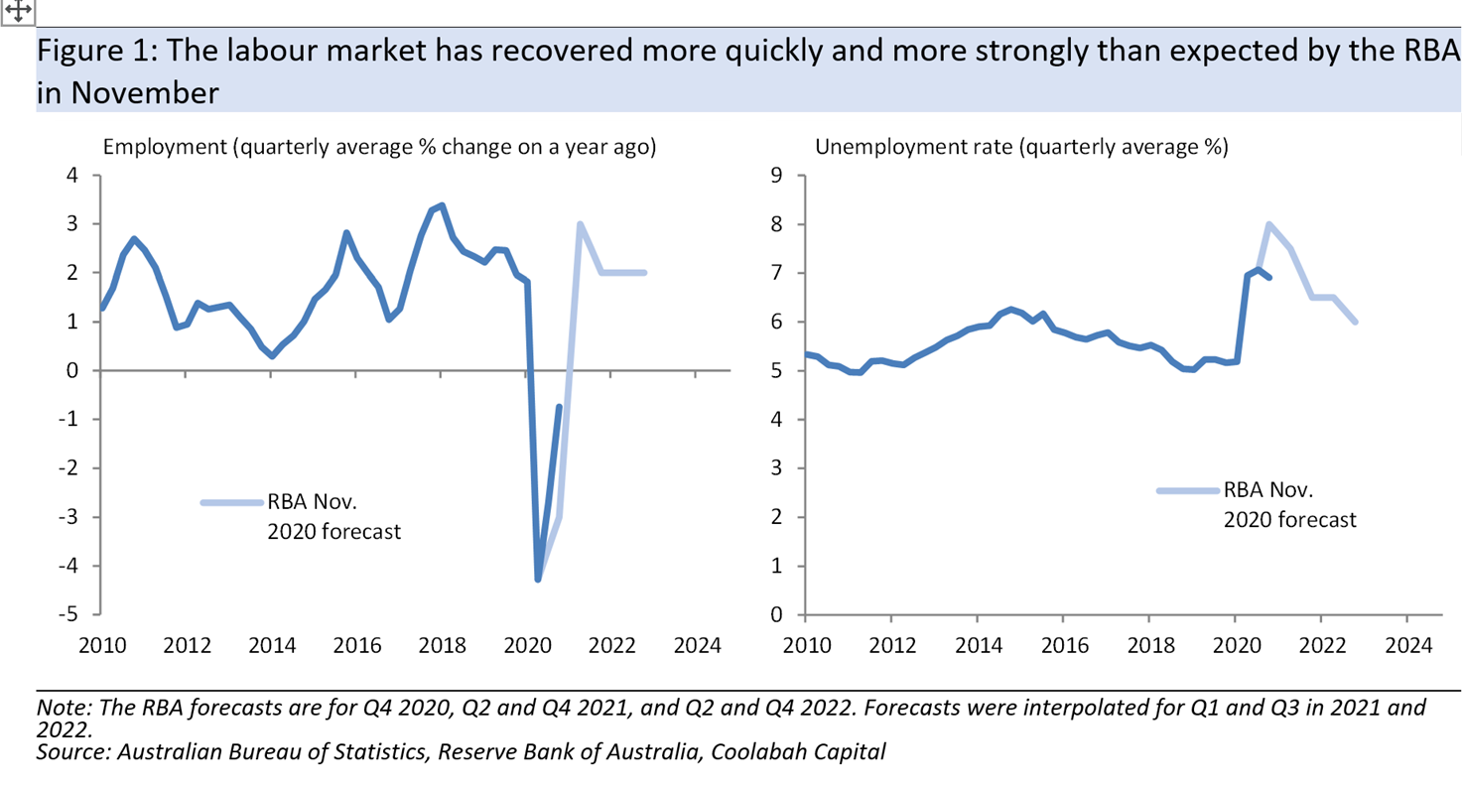

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) board meets on 2 February to decide policy based on updated staff economic analysis and forecasts, which will show that domestic activity and the labour market have recovered more rapidly and robustly than the RBA expected, consistent with Coolabah Capital Investments’ (CCI’s) priors. While this will be welcomed by Governor Philip Lowe when he speaks on the economy and policy the next day, CCI believes he will remain cautious about the medium-term outlook given his ambitious aim of achieving full employment, which the RBA says is equivalent to reducing the unemployment rate to “4-point something” per cent, juxtaposed against a patchy global outlook ridden with second and third waves and harsh lockdowns in key developed economies.

Full employment is crucial to lifting wages above 4% to return core inflation to the RBA’s target 2% to 3% band. The last time Australia experienced full employment was prior to the global financial crisis (GFC), which explains why the RBA has consistently undershot its inflation target in the years leading up to the pandemic. Lowe will also be mindful that Australia still confronts many important challenges: the global economy is experiencing a fresh setback from COVID-19, with lockdowns in Europe, the UK and US, amongst others; a serious, albeit one-sided, trade war has erupted with China; much of the federal government’s massive fiscal stimulus is unwound this year; and the international border likely won’t open until 2022/2023 given Australia’s tough and highly successful approach to managing the pandemic.

With the RBA a long way from its economic objectives, the Taylor rule from the RBA’s MARTIN macroeconomic model points to the need for a strongly negative cash rate: as much as -3¾% in 2021. Since Lowe has all but ruled out negative rates, the RBA will have little choice but to furnish additional unconventional monetary stimulus in 2021 and, to a lesser extent, in 2022. Quantifying how much extra support is required is difficult, but CCI expects that the RBA will extend its existing quantitative easing (QE) program, which is due to expire in April, for another six months with a similar, c.$100bn commitment to relieving upward pressure on Australia’s high long-term bond yields and the trade-weighted exchange rate.

Although we don’t have high conviction on the size of QE 2.0 (there are credible arguments in favour of a significantly bigger commitment), we agree with Deputy Governor Debelle when he remarked last year, “I think in the situation we're in at the moment, I would certainly think the right decision is to err on too much support rather than too little support”.

If anything, market participants may be underestimating the possibility of a larger program given that the key learning from QE 1.0 is that the RBA has not done enough to achieve its macro aims, as reflected in a higher Australian dollar. This is reinforced by the fact that both the cash rate and the 3-year government bond yield are at their effective lower bound (the 3-year rate is being managed under the RBA’s yield curve control policy). A final consideration is that banks have not materially drawn on the RBA’s c. $180 billion term funding facility (TFF) since October 2020 because they are awash with excess liquidity in a world where balance-sheet growth remains very weak. The last remaining policy tool with substantial untapped potential is QE targeting long-dated bonds, which also has the very attractive benefit of having little impact on housing market dynamics given most Australian home loan borrowers use variable or short-term fixed-rate products. It does not, therefore, trigger the financial stability concerns associated with other more conventional monetary policy tools.

There is also a case for the RBA to take this opportunity to fine-tune the mix of its purchases of Commonwealth and state government bonds to 70%/30%, more in line with the relative weights in the stock of outstanding debt. The RBA had previously underweighted its purchases of state bonds (or “semis”) over concerns about liquidity in the market, which proved unfounded even following the announcement of much larger state budget deficits and the rating downgrades of NSW and Victoria. In fact, all the evidence suggests that the RBA has uncovered enormous offer-side liquidity in the semis market, buying most of its bonds very cheaply at or wide of the mid credit spread (i.e. not at the offer as would normally be the case).

The market consensus is for an extension of QE in April with most expecting another $100bn round of purchases, while some banks look for a smaller extension. There are also some early indications that the RBA’s favoured media proxies are validating the concept of QE 2.0. Surprisingly, no economists are currently canvassing a larger package, although Westpac is factoring in additional purchases next year. Some banks believe that the RBA might soon modify its 3-year yield target, but CCI thinks it will probably remain in place for a while longer, assuming QE is extended. Over time the RBA might have to rethink its options if its bond purchases fail to keep pace with the monetary stimulus from other central banks and the real exchange rate continues to appreciate. One cannot rule out direct currency interventions, as was more common in the 1990s, although this raises the spectre of the RBA being criticised globally as a currency manipulator.

The RBA board will formally upgrade its near-term economic outlook

The RBA board meets for the first time this year on 2 February. The policy discussion will be based on updated staff economic analysis and forecasts, where much has happened since the last set of estimates were prepared in November. Governor Lowe will then talk the next day about the economy and policy a speech entitled “The year ahead”, with the RBA publishing revised forecasts in its 5 February Statement on Monetary Policy.

The RBA has already foreshadowed a significant upgrade to the near-term outlook given that the economy has outperformed expectations, with activity recovering sooner and more strongly than expected. The same is true for the labour market, with employment almost back at pre-pandemic levels, something the RBA did not think would be achieved until mid this year. Importantly, the peak in the unemployment rate has undershot the RBA’s forecast of 8%, with quarterly average unemployment peaking at 7.1% in Q4 and the monthly rate ending the year at 6.6%, a level the RBA had thought would not be reached until mid 2021.

Disappointingly, though, inflation and wages growth remain very weak. Inflation had been stuck below the bank’s 2% to 3% inflation target for several years prior to the pandemic and ended last year slightly above 1%, marking the lowest annual rate since the early 1960s. Very low inflation reflects hardly any growth in wages, low inflation expectations, and weak housing costs.

History still suggests it will take time to return to full employment,

while financial stability risks have abated

Governor Lowe will naturally welcome this upgrade, although we think he will remain cautious about the medium-term outlook, noting his remarks in December that although “the bounce-back has been quicker than we’d hoped” it was “not changing the medium term”. This leads us to think that the RBA will still forecast inflation remaining below the 2% to 3% target band given the substantial spare capacity in the labour market. Estimating spare capacity is challenging, but Lowe believes that “we've got to get back to an unemployment rate of 4-point-something to get the type of wage pressures that will deliver inflation outcomes consistent with, on average, 2½ per cent”, which “still seems a long way away”.

Caution about the medium-term outlook seems warranted given:

- A weaker world economy. The global economy has had a significant near-term setback from the latest surge in the virus and the ensuing lockdowns in Europe, the UK and the US, while the distribution of the vaccine in the larger advanced economies has been slow. Indeed, international disputes regarding vaccine distribution are now emerging between the EU and the UK. Developing economies face a much longer timetable to innoculate their populations, which could present another serious headwind for global growth. This is likely to see ongoing monetary stimulus from the major central banks that a characteristically more conservative RBA will find tough to match, which helps explain the recent appreciation in Australia’s trade-weighted exchange rate.

- A one-sided trade war with China. China has sought to make an example of Australia by punishing the Morrison government for calling for an independent international inquiry into the origins of COVID-19. This has involved imposing tariffs and bans on a range of Australian exports, most importantly coal, but also copper, wine, beef, barley, cotton, seafood, and timber. Merchandise exports to China are still holding around very high pre-pandemic levels, but this reflects surging iron ore exports offsetting the impact of trade restrictions. The downside risk is that the relationship continues to deteriorate over external events, such as Chinese incursions into Taiwan, and that Chinese sanctions extend to iron ore. CCI believes there is a nontrivial risk of war between China and the US over Taiwan, which would make it hard for Australia to export any iron ore, coal, or natural gas to the Middle Kingdom.

- The unwinding of a gigantic fiscal stimulus. Australia’s unprecedented fiscal stimulus, which saw the largest peacetime budget deficits on record, is largely temporary by design. The private sector has saved some of this stimulus, but fiscal policy will be sharply contractionary over the course of 2021 as labour market subsidies, temporary welfare payments and housing grants roll off. This impulse is likely amplified by the Morrison government’s relatively parsimonious approach to fiscal policy, and the political preference to reduce the deficit as quickly as is reasonably possible with one eye on the next election.

- Re-opening Australia’s border remains a long way off. The government anticipates that it will take until October for most Australians to be vaccinated, with the chief medical officer suggesting it was too early to say if the international border will open in 2021. Labour supply will also be significantly constrained by practically no growth in the working age population until international migration resumes. Given the government’s aggressive COVID-19 elimination strategy, opening the border will require foreign nations to have likewise eliminated the virus, which is improbable in most countries in 2021. A recent example is the government’s decision to shut the New Zealand travel bubble following one case of community transmission. A best-case scenario would involve exports of education services and tourism normalising in 2022 or 2023, although domestic tourism will provide some offset in the interim as more Australians take local holidays. Significantly, Australian tourism abroad outweighed international tourist spending in Australia by 0.8% of GDP prior to the pandemic.

The RBA would also be sensitive to the fact that since the GFC it has struggled to reduce the unemployment rate below 5%, which is one key reason why wage growth has failed to return to its pre-crisis average of about 3.5%.

After all, the RBA’s MARTIN macroeconomic model suggests wage growth will have to average about 4.5% for to achieve a 2.5% inflation rate, the midpoint of the 2% to 3% target band. The last time unemployment was consistently in the 4-point-something band was in the early stages of the GFC and before that the 1970s.

Indeed, past recessions suggest that lowering unemployment is difficult, with reductions similar to that which the RBA is currently targeting achieved on a sustained basis about 4 to 5 years after the peak in unemployment in only two of the five previous recessions since 1960 (and not achieved in the years after the GFC).

Put differently, there is a high risk that the RBA fails to meet its current policy priority of delivering full employment with the consequence that wage growth proves too low to return inflation to its target band, as was the case in the years leading up to the pandemic. In that earlier episode, the RBA tolerated some miss on its economic targets because it was exercised about risks to financial stability.

Those risks have long since eased, with slow growth in housing credit and national dwelling values only recently matching the peak reached in 2017 (Sydney and Melbourne prices are still 4% below their previous highs).

Although some market participants expect the RBA will soon taper its support for the economy given the near-term rebound in the economy, we place more emphasis on Deputy Governor Debelle’s views, who argued at the end of 2020 that a key lesson for policy makers is to “be careful of removing the stimulus too early”. Accordingly, given the absence of financial stability concerns, we think the prudent course of action for the RBA is to err on the side of more, rather than less, stimulus in order to obtain its macroeconomic goals.

Interest rate rules highlight the need for significant unconventional support

In judging how the revised economic outlook could influence policy, we are mindful that the RBA is downplaying the usefulness of forecasts given we are in the middle of a once-in-a-century pandemic. This is evident in the board’s unprecedented forward guidance that the bank will not raise the cash rate until “actual inflation is sustainably within the 2‑3% target range”, which means “wages growth will have to be materially higher … (something that requires) significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market” (emphasis added). On the RBA’s November outlook, this meant the board did not expect to increase the cash rate “for at least three years”.

To explore this issue, CCI forecast the RBA’s cash rate using the Taylor rule from the RBA’s MARTIN macroeconomic model . This rule sets the cash rate as a function of the real neutral cash rate, forecast underlying inflation relative to the RBA’s target, and forecast unemployment relative to the NAIRU, where we assumed:

- The real neutral cash rate has declined from the RBA’s estimate of about 0.75% at the end of 2019 to about 0.5% in 2020 given the wider spread between lending rates and the cash rate.

- The NAIRU equals 4.5%, which is the midpoint of Governor Lowe’s characterisation of an “unemployment rate of 4-point something”. This assumption is possibly optimistic given the NAIRU normally increases in a recession, but likely reflects: (1) Lowe being influenced by the pre-pandemic experience where a 5% rate was not low enough to generate sufficient wages growth return inflation to target; and (2) the fact that the RBA’s pre-COVID-19 NAIRU estimate was trending towards 4.5%.

- A forecast outlook for unemployment based on the consensus market view, which has a lower profile than the RBA’s estimates, and a forecast outlook for inflation based on the RBA’s November estimates, much the same as the market’s profile.

On this basis, the rule points to a significantly negative cash rate of about -3¼ to -3¾% in 2021 and -2 to -3% in 2022. Given that the RBA regards 0.1% as the effective lower bound for the cash rate and the 3 year government bond yield, this points to the need for very significant unconventional monetary policy to be maintained in 2021, with some winding back in 2022.

CCI expects another c.$100bn round of bond purchases with a tweaked mix, but there are risks to the upside

Assessing whether the unconventional steps taken by the RBA to date are sufficient to achieve the same result as a strongly negative cash rate is difficult. Prior to the latest round of measures, CCI estimated that the RBA’s optimal unconventional policy stimulus using the MARTIN model to calculate how far conventional policy would take the economy towards full employment. We then assumed that the RBA would have to increase its balance sheet via unconventional measures to close the gap.

Making the strong assumption that international research on the economic impact of central bank balance-sheet expansion applied to Australia, CCI estimated that the RBA would need to buy c.$140bn of longer-term Commonwealth and state government bonds, in addition to the purchases required to maintain the target for the 3-year Commonwealth bond yield and the expansion in the balance sheet due to the TFF supplying cheap 3-year funding to banks.

We thought the purchases would take place over a year and be tied to the RBA’s economic objectives. As it turned out, the RBA front-loaded the purchases, announcing a $100bn programme, split 80%/20% between Commonwealth and state government bonds, with a commitment to buy more bonds if required.

This time, rather than rely on international experience with unconventional policy, we leveraged off recent research by the RBA. This analysis examined the impact of conventional and unconventional monetary policy using the MARTIN model, where the bond market and exchange rate were allowed to be more responsive to policy expectations. It showed different policy options have varying effects on the labour market. Specifically:

- Conventional policy. A sustained 100bp reduction in the RBA’s cash rate reduces the unemployment rate by 0.8pp;

- Forward guidance and bond purchases. A 100bp reduction in both short- and long-term bond yields relative to the rest of the world reduces the unemployment rate by about 0.6pp, almost wholly via a 6% reduction in the real exchange rate. Lower bond yields were seen as reflecting forward guidance and a yield target, but could be thought of as mimicking the current policy combination of forward guidance, the 3-year yield target and outright purchases of longer-term bonds; and

- Bank financing. A 100bp reduction in mortgage rates independent of the cash rate lowers the unemployment rate by about 0.4pp. The same reduction in business lending rates has a smaller impact of about 0.1pp. As the RBA notes, this type of reduction in lending rates could be achieved via the TFF and by the impact of lower government bond yields on bank funding costs.

On this basis, the reduction in the cash rate from 1.5% in 2019 to 0.1% in November last year should eventually reduce the unemployment rate by 1.1pp. However, the RBA’s bond purchases and the TFF have not had much of an impact as yet, at least judging by the modelling framework employed by the central bank.

In the case of bond purchases, this is because both short- and long-term bond differentials are little changed from either prior to the introduction of the yield curve target in March or the advent of outright QE in November. More importantly, Australia’s real exchange rate—where the lower currency is the critical transmission mechanism for QE in the RBA’s analysis—ended last year 6% higher than the end of 2019.

The RBA acknowledges that bond purchases can have other effects, such as the well-known portfolio balance effect of forcing investors to search for higher-yielding assets, cash-flow effects on government budgets, and contributing to lower fixed-rate lending rates. Yet the main way in which the RBA models the impact of price- and quantity-based QE does not seem to have worked to date. Put more pointedly, the size of the RBA’s QE program has been too small to achieve the fall in bond yields needed to lower the real exchange rate because it has been overwhelmed by countervailing forces—most notably more aggressive monetary policy stimulus in the larger economies and soaring commodity prices—pushing the currency higher.

In the RBA’s defence, the counterfactual in which it engaged in no QE would have been a lot worse; that is, Australia would be facing materially higher bond yields and a loftier real exchange rate, dampening growth further. And the RBA has been frank in acknowledging that QE 1.0 was going to render important data and insights on the magnitude of the interventions required to achieve its desired policy outcomes.

As for cheap financing to banks, funding costs have improved by about 100bp from before the pandemic, with large declines in bank bond spreads, overall yields, and deposit rates. However, spreads of business and housing interest rates for new loans over the RBA’s cash rate are almost unchanged. The TFF has undoubtedly improved the availability of credit, although this is hard to quantify given that the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority does not publish its survey of lending standards like central banks in every other advanced economy.

Wholesale bank funding markets were clearly shut through the first half of March, and were it not for the TFF and the RBA’s other essential direct lending operations effected via repurchase agreements, access to funding would have been severely curtailed and the cost of that funding, which reached record levels in some parts of the capital structure in March when measured against risk-free rates, would have continued to explode. Accordingly, the TFF has been a crucial part of the RBA’s unconventional policy toolkit that prevented radically higher bank funding costs, which would have been passed on to customers. This counterfactual would have obviously exacerbated the COVID-19-induced recession.

So while the TFF has made a significant contribution to maximising the liquidity and solvency of the financial system, supporting the profitability of banks, and preventing the adverse economic consequences flowing from much higher bank funding costs, it has not yet translated into large reductions in lending rates independent of the cash rate. That may eventually come as the RBA anticipates that banks will draw on the remaining $101bn in the facility as applications for additional funds close in June.

With unconventional policy struggling to date to contribute to reducing the jobless rate, it is more likely that the improvement in employment growth reflects a combination of the above-mentioned role of the lower RBA cash rate, the massive fiscal stimulus targeted at the labour market, and the exceptional success of Australia’s health policy in containing recent outbreaks. The problem for the RBA is that the fiscal stimulus will be unwound this year and upward pressure on the exchange rate is likely to continue given ongoing monetary easing from other central banks. Indeed, currencies are coming into focus globally with central bank governors in Europe highlighting the elevated level of the euro as potentially warranting yet more easing.

All this suggests that further unconventional policy support is required for the RBA to achieve its target of full employment. Quantifying how much further QE support is required is difficult, but CCI expects that the RBA will extend the existing program, which expires in April, for another six months with a c.$100bn commitment to reducing Australia’s globally elevated long-term risk-free rates over the 5 to 10 year tenors.

We do not have high conviction on the exact size of QE 2.0, although we believe that the market is underestimating the possibility of a bigger, rather than smaller, QE programme. QE 1.0 has provided the RBA with crucial insights on its transmission mechanism, where the main lesson has been that the RBA has not expanded its balance-sheet fast enough to keep pace with its peers overseas.

Here we concur with Deputy Governor Debelle when he commented last year, “I think in the situation we're in at the moment, I would certainly think the right decision is to err on too much support rather than too little support … (where) the main point has been to provide the appropriate degree of support for the economy”.

While the RBA might not enthusiastically embrace QE, it has been explicit in highlighting that its decision to expand its balance-sheet necessarily incorporates the actions of other global central banks to place the Australian economy, and our real exchange rate more specifically, on a level playing field.

As Governor Lowe put it, “ (Australia is) part of an international financial system and we have to respond to what others are doing … (given) there is a very strong gravitational pull from the level of global interest rates”.

In a world of invidious choices, this is undeniably the RBA’s least-worst policy solution if it wants to meet its legislated full employment objective, where the RBA’s board has repeatedly stressed that it views “addressing the high rate of unemployment as an important national priority”.

The RBA knows that it needs to very materially reduce the jobless rate to normalise wages growth, which is essential for a sustainable return of inflation to its target band. And the key take-away from the post-GFC period is not to be satisfied by strong employment growth that only achieves a jobless rate of 5-point-something per cent, given that proved inadequate in generating the wages growth sought by the RBA.

Surveying 11 leading banks, seven expect the RBA to extend QE with another $100bn commitment. Four banks believe the RBA will extend with a smaller $50 to $75bn initiative, while one bank is undecided on the size. While all banks forecast that the RBA will launch QE 2.0, we find it somewhat surprising that no bank projects a bigger commitment, even if it is a small increase over the existing programme, given the modest results flowing from QE 1.0. (Westpac is forecasting additional QE in 2022.)

The RBA is likely to take the opportunity to recalibrate the mix of purchases of Commonwealth and state government bonds to 70%/30%, which is more in line with their relative shares of the stock of outstanding government debt. The RBA had previously underweighted its purchases of state government bonds, which only accounted for 20% of the current QE program, likely given claims that there might not be sufficient offer-side liquidity in the “semis” market. Yet with the explosion in state government spending on the RBA’s explicit and enthusiastic encouragement, and the resultant ballooning in state budget deficits, the RBA has been inundated with liquidity in its semi-government bond purchases to date.

In fact, in December and early January credit spreads on semi-government bonds were materially wide of the tights recorded after the RBA announced QE in November as a result of larger-than-expected state budget deficits and NSW and Victoria losing their prized AAA ratings with Standard & Poor’s (they remain AAA-rated by Moody’s). There is little doubt that were it not for the RBA repeatedly pushing the states to spend a lot more, NSW and Victoria’s credit ratings would be higher today.

Some banks believe that the RBA might soon modify its 3-year yield target, but we think it will probably remain in place for a while longer assuming QE is extended. Over time the RBA might have to rethink its options if its bond purchases fail to keep pace with the monetary stimulus from other central banks and the real exchange rate continues to appreciate. One cannot rule-out direct currency intervention, as was more common in the 1990s, although this raises the spectre of the RBA being criticised globally as a currency manipulator.

Much greater QE might be warranted if our assumptions regarding the path of the virus prove incorrect. We assume Australia will maintain its success in de facto eliminating the virus while the developed world normalises over time as vaccines eventually furnish herd immunity. Of course, risks to this outlook include mutant strains that are resistant to vaccines, more secular side-effects that prevent mass-market deployment, and/or a deterioration in efficacy rates that undermine the prospects for herd immunity.

On the other hand, the RBA might choose to aggressively taper its current QE program in the next 2.0 iteration if for some reason it felt unexpectedly satisfied with the improvement in the labour market to date, and was willing to tolerate a much longer glide path back to full employment and the inflation target. Given the profound difficulties it has had delivering the wage growth required to sustain inflation in its target band since the GFC, this latter scenario would seem to be low probability.

This assumes trend growth in labour productivity of 1-1.25%, lower than the RBA’s assumption of 1.5%.

Access our intellectual edge

Coolabah Capital Investments publishes its timely insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid with our unique contrarian philosophy. Click the ‘FOLLOW’ button below and never miss our updates.

2 topics