RBA predicted almost no house price declines when it hiked rates, but now expects the biggest declines ever...

In a fascinating RBA freedom of information disclosure dumped on Friday, which references Coolabah's house price analysis/forecasts (including work published here on Livewire), the Australian central bank reveals how it once again got its house price expectations wrong--and then radically downgraded them.

The massive shift in the RBA's house price outlook almost certainly has implications for how high it needs to lift its cash rate: it has gone from predicting almost no house price declines to what would be--in its own words--the biggest draw-down in history.

Recall that back in October 2021 we argued that after the RBA lifted its cash rate by at least 100 basis points, national house prices would fall by 15-25%. No other mainstream analysts were forecasting material house price declines at the time.

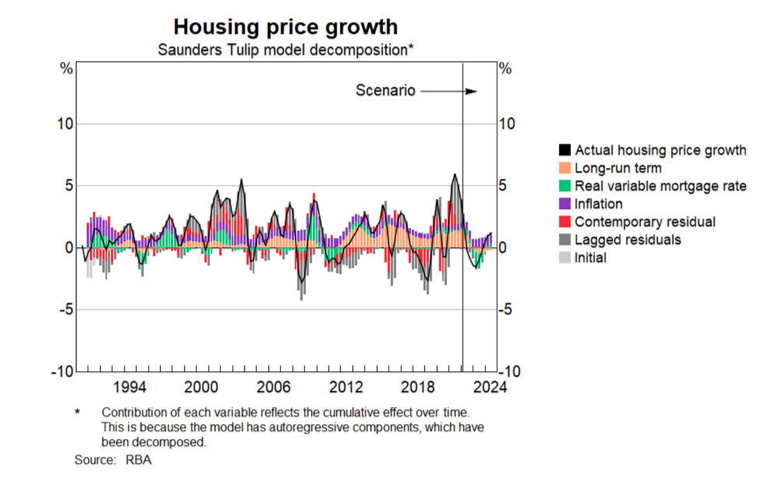

Our contrarian views were partly predicted on the insights afforded by the RBA's key internal housing model, developed by Trent Saunders and Peter Tulip, which we had refined, updated and then applied repeatedly in 2021.

Back then I had asked our chief macro strategist, Kieran Davies, to reach out to one of the model's developers, Peter Tulip, to help us understand, improve and apply the model. This process uncovered some wrinkles in the model that needed to be ironed-out. While the RBA repeatedly puzzles as to how to reconcile Coolabah's application of the Saunders-Tulip model with its own efforts (we forecast big house price declines while the RBA initially struggled to arrive at this finding), it never reached out to either Tulip or ourselves for assistance, which I know both parties would have been happy to supply.

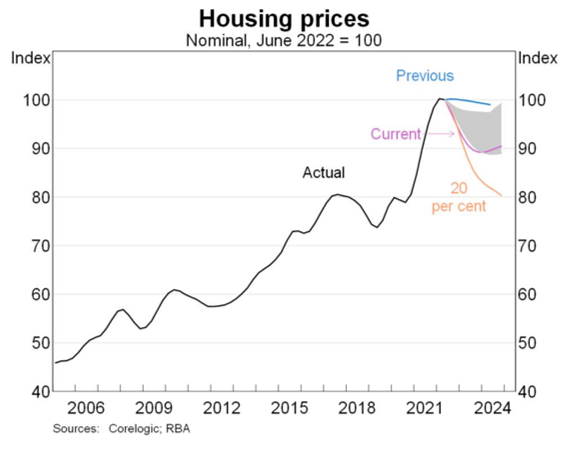

In a forecasting meeting in 2022, the RBA presents the following chart that applies the Saunders-Tulip model. Observe that this particular iteration of the model anticipates only a very modest dip in house prices of less than ~2% (black line in chart below). This notably conflicts with our version of the model, which pointed to a much larger, circa 30% decline in house prices (see here).

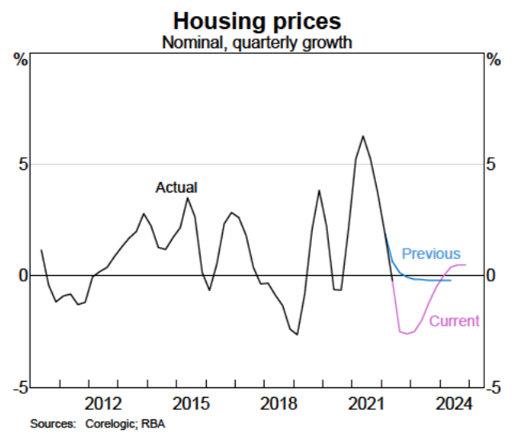

Yet by July, the RBA had radically modified its house price forecasts, commenting that "the profile for housing price growth had been downgraded":

"Housing prices unexpectedly declined in the June quarter, and the higher path for interest rates has pushed down the profile relative to the previous [May] Statement [on Monetary Policy]. In addition, we have applied some downward judgement to our housing price profile to reflect downward momentum in the housing market. House prices are now expected to decline by 11% by mid 2023."

The major shift in the RBA's view on house prices is elegantly captured by this previously unpublished chart. Observe the blue line from the RBA's May Statement on Monetary Policy, which was published after their very first interest rate increase, projects almost no price declines. The upgraded August forecast, which is the pink line, forecasts a record 11% drop in national house prices, which is now much closer to our 15-25% forecast from October 2021.

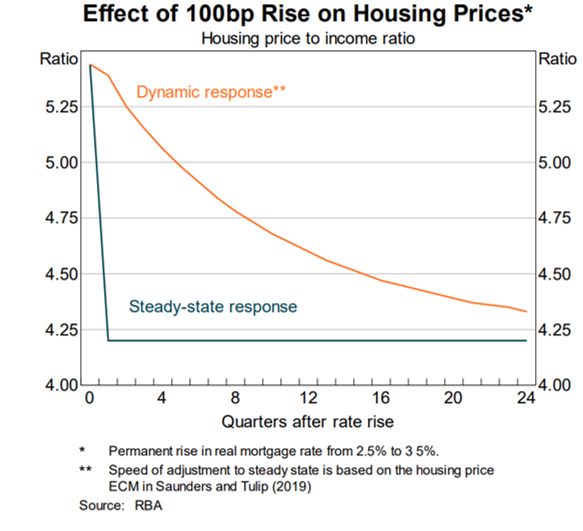

In the same month, an internal RBA research paper was prepared that examined the impact of changing mortgage rates on house prices using a variant of the Saunders-Tulip model. The unnamed author comments that "given the current focus on rising long-run rates after decades of decline, I illustrate the effects of a 100 basis point increase in the mortgage rate from 2.5 to 3.5 per cent, assuming the model starts in equilibrium". This is much closer to our original application of Saunders-Tulip in 2021. And, unsurprisingly, the RBA economist finds that:

"[House] prices gradually decline toward their new steady state level, 22 per cent lower than the pre-shock level."

We had published our original 15-25% house price decline forecast in October 2021 assuming the RBA permanently hiked interest rates by at least 100 basis points. On 17 June 2022 here at Livewire, we published a more detailed analysis of our upgraded Saunders-Tulip model applying a scenario--similar to market pricing at the time--that involved the RBA hiking rates temporarily to 4.25% and then cutting rates in 2023 and 2024. The findings implied a somewhat larger peak-to-trough decline in prices of circa 30-40%. (We did not, however, change our official central case of a 15-25% peak-to-trough decline, partly because we did not agree with market pricing for the path of the RBA's cash rate.)

In its FOI disclosure on Friday, the RBA revealed numerous internal emails discussing Coolabah's research that sought to reconcile our results with the RBA's own variant of the Saunders-Tulip model.

An economist at the RBA asks an unnamed colleague, "why do we generate relatively minor house price declines with the [Saunders-Tulip] model, while Coolabah (Joye) generates 20‐ 30% declines? Our assumed cash rate profile seems broadly the same."

In one email response, an unnamed author comments "this is a [question] that has puzzled me in the past" and then goes on to posit a few explanations for the differences in the RBA's forecasts using the model and Coolabah's findings. In a second email, possibly from a different person, an RBA economist adds to this discussion, commenting:

"I’ve also done some work trying to replicate the following article: "RBA model points to

a house price slump of around 30% ‐ Kieran Davies | Livewire (livewiremarkets.com)". The key differences in

assumptions are:

- [Coolabah] look at a horizon until the end of 2025.

- A steeper cash rate of 3.6 per cent by end of 22, 4.2 per cent by end of 23, 4 per cent by end of 24, and 3.7 per cent by end of 25.

- [Coolabah's] working age population assumption assumes that growth rates remain at where they currently are.

- They’ve also said they’ve refined the model since it was published, but haven’t revealed what they’ve done. [Note the RBA never asked us about the wrinkles we found.]

- They’ve used their interpretation of the May SMP forecasts for other economic variables.

Running this scenario, real [house] prices decline by around 20 per cent to the end of 2025. Comparing this with a flat cash rate path of 0.39 per cent across the horizon and also a flat 10Y bond yield (and other variables following the May SMP), this is around 25 per cent below this scenario. Relative to the Aug 2021 SMP ST scenario, it is also around 20 per cent below the baseline. I’m currently working on comparing our current Saunders-Tulip runs to the scenario runs you outlined Tim."

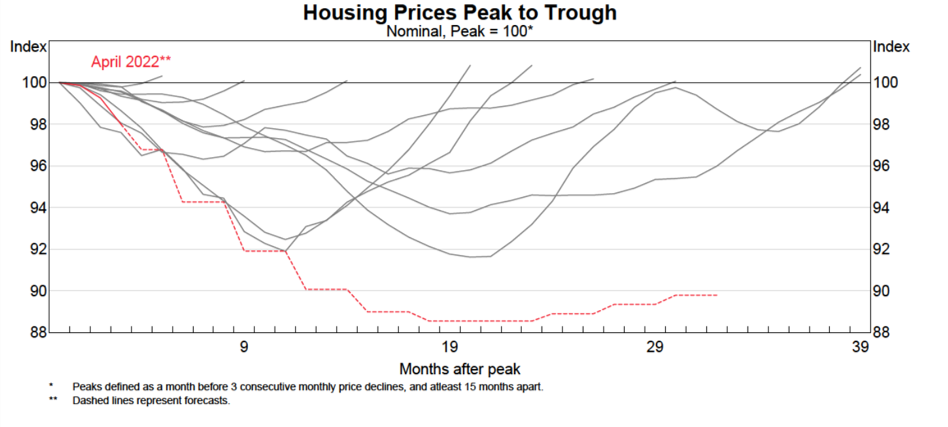

In a separate presentation, the RBA considers how their new, much more dire, forecasts for house prices compare to other housing market corrections since 1980. They comment:

"In real [inflation-adjusted] terms, prices are forecast to decline by almost 20 per cent (Graph 4). This is also the biggest decline since at least 1980. The previous real‐terms decline that comes closest to that forecast is the 1982 episode."

The RBA went on to develop a downside scenario using the Saunders-Tulip model where they adjusted their assumption regarding households' expectations of future house price growth from a positive to a negative number. Specifically, they comment:

We’ve constructed a downside housing price scenario within the Saunders Tulip framework by assuming people become pessimistic about the outlook for housing prices. That could be a response to ongoing price declines, or could be prompted by higher interest rates. Specifically we adjust the expected capital appreciation term to be -1.5% pa rather than the long run average of 2.6% pa. In this scenario, housing prices decline by 20 per cent peak-to-trough by the end of 2024. So this is roughly twice as large as what we’ve assumed in our baseline, and sits below the range of estimates from our suite of models and most market economists.

The RBA's original house price forecast when it first started hiking rates assumed a negligible change in valuations. Within a few months it had moved to predicting the biggest drop in prices on record. This has nontrivial consequences for the RBA's expectations for consumption, building, demand, growth and ultimately the appropriate path of monetary policy.

We would argue that the RBA has consistently got housing market movements wildly wrong since 2013, when it failed to anticipate the huge housing boom that emerged following aggressive interest rate cuts. It also failed to predict the record house price correction between 2017 and 2019 in response to higher mortgage rates resulting from APRA's application of its macroprudential policies. It further missed the 10% boom between 2019 and 2020 as rates were cut, the tiny 2% dip between March and September 2020, the subsequent 20-30% boom in response to both monetary and fiscal stimulus, and now the record correction that commenced in May 2022 in response to its record interest rate increases. We were on the right side of all these moves.

If the RBA cannot understand why its forecasts differ from our own, it should just reach out and we would have been delighted to explain how we refined the Saunders-Tulip model. They could have also engaged with Peter Tulip, who I am sure would have been happy to render the same insights he furnished us.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers.

2 topics