Recession, rates, rising risks: The rationale for remaining positive

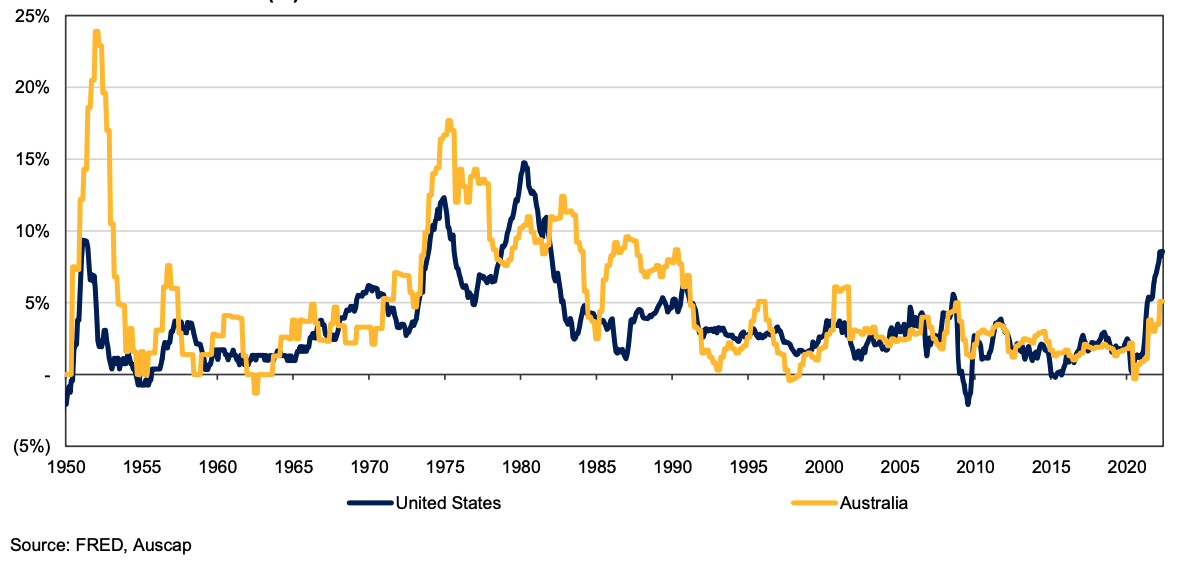

Inflation is the topic du jour. And for good reason. Inflation in the United States is at the highest level in 40 years, running at a staggering annualised rate of 8.6%. In Australia, inflation was 5.1% at the end of March, the highest reading in over 20 years. As a result, market participants are fixated on the impact to financial markets from central banks trying to lower these numbers through interest rate increases. But as legendary investor Stanley Druckenmiller has said, “never, ever invest in the present ... you have to visualise the situation 18 months from now, and whatever that is, that’s where the price will be.”

Chart – CPI Growth Annualised

It is worth considering what inflation is likely to be in a year’s time. To do this, one needs to understand why it is so elevated currently.

US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has identified three overlapping root causes for the current global spike in inflation: the war in Ukraine (impacting agricultural, chemical and energy commodity prices), disruptions to global supply chains (including shipping costs, Chinese lockdowns and semiconductor shortages) and the interaction of tight labour markets with strong demand conditions. We would add expansionary monetary and fiscal policy to this list.

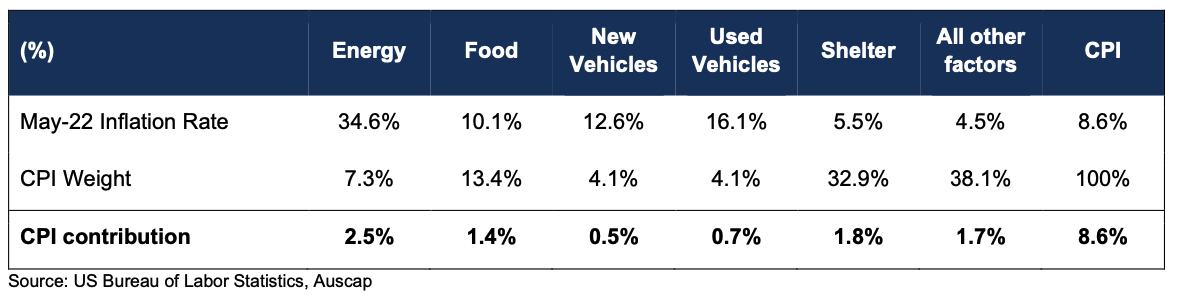

The most recent US inflation reading was largely driven by three consumer price index (CPI) components with high weightings: energy, food and vehicle prices. Growth within these areas directly represented about 60% of the 8.6% inflation number, despite an approximate weighting in the CPI basket of only 29%. We think it is important to analyse input price trends in these individual categories to understand the likely forward trend in inflation.

Energy

Energy prices are a direct component of the CPI and have wide indirect impacts, such as on transportation costs and agriculture prices. The WTI Crude Oil Price reached $130.50 in March 2022, soon after the Ukraine conflict began, but has since drifted 22% lower, to now sit at approximately $102.

West Texas Intermediate (WTI) Crude Oil Price (USD

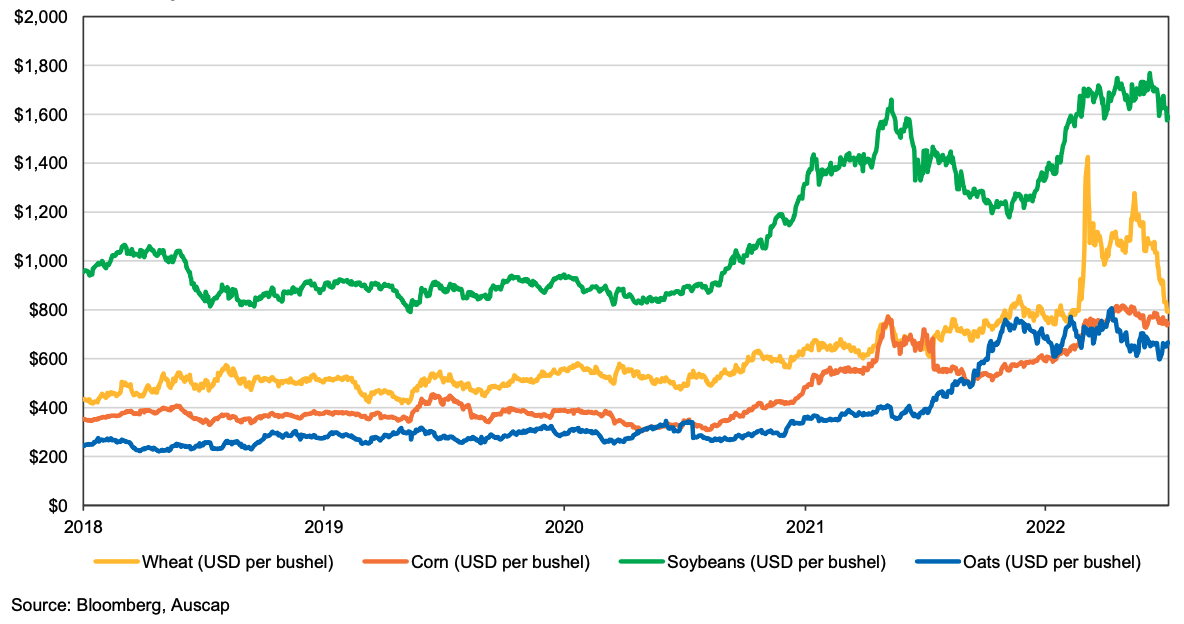

Food

Key agricultural commodities such as wheat, corn and soybeans rose sharply in the second half of 2021 and the start of 2022, but have since either stopped increasing or begun to fall.

Soft Commodity Prices: 2018 to Present

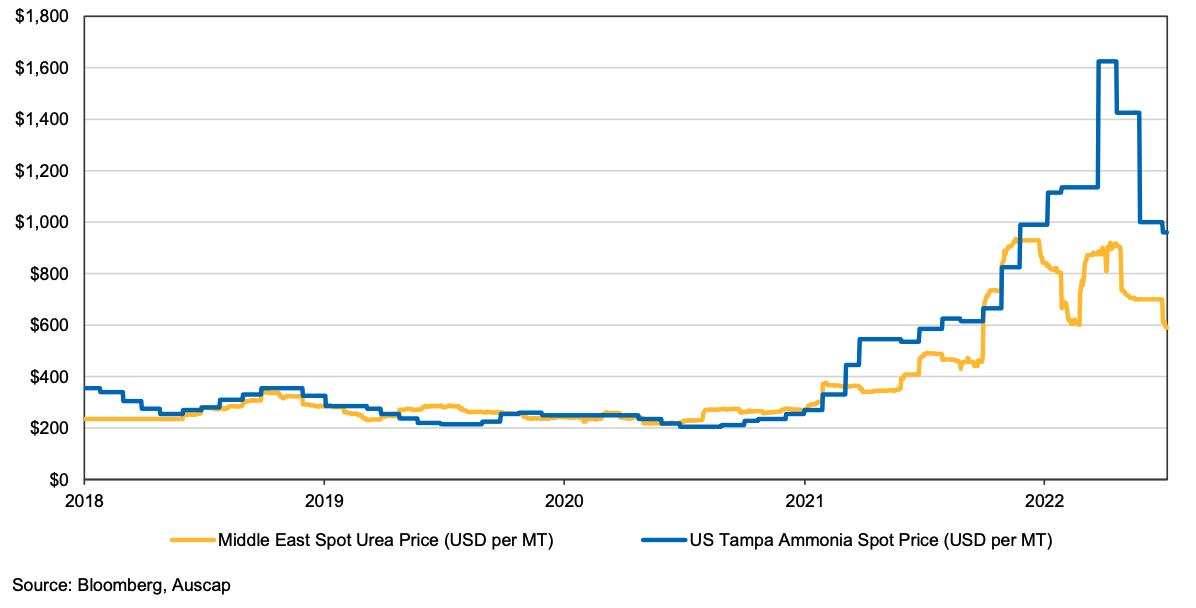

Two of the major input costs into fertiliser, and therefore food prices, are urea and ammonia. Both commodities have seen significant price increases from the start of 2021. These have recently begun to abate, albeit prices are still very high compared to previous years.

Fertiliser Input Commodities: 2018 to Present

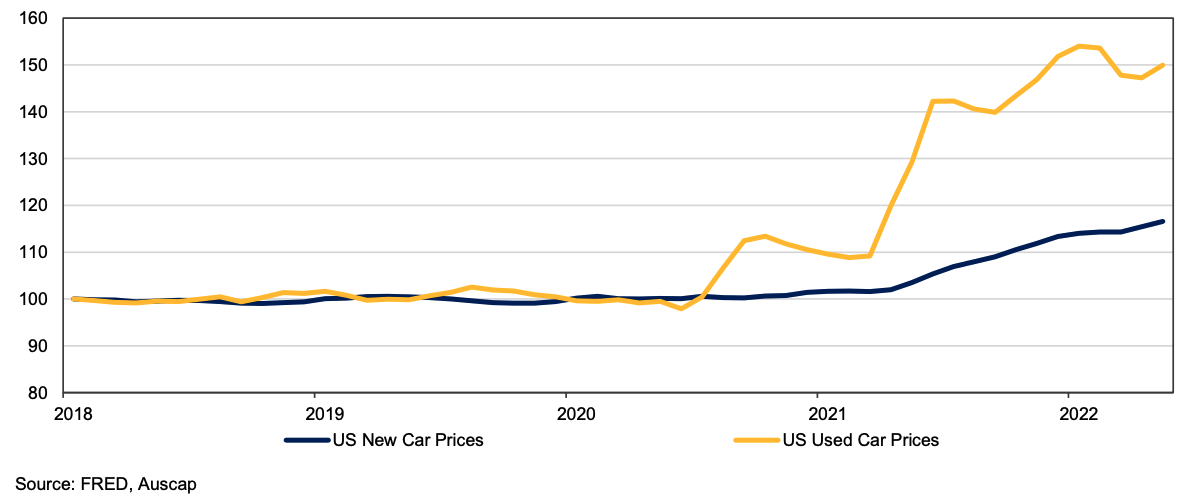

Vehicles

In the United States, used vehicle prices peaked in February 2022, having experienced their sharpest increase on record in April – June 2021, the period we are now cycling.

US New & Used Vehicle Prices (Index rebased to 100)

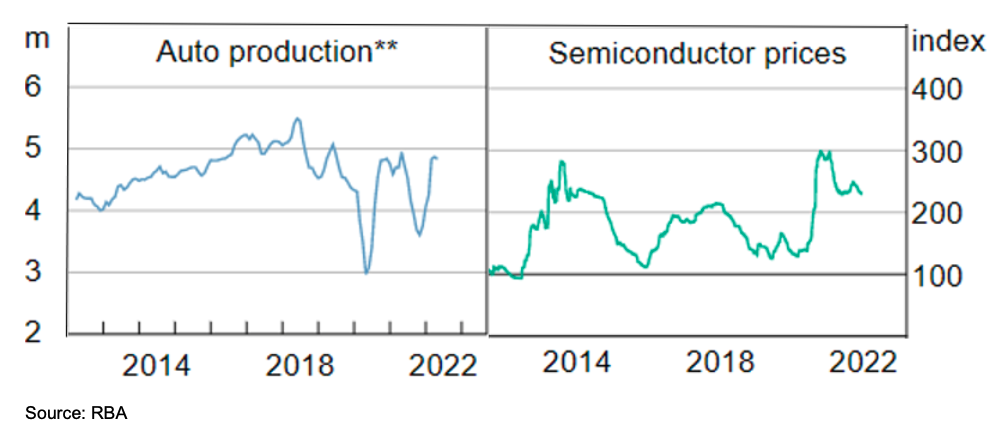

While new vehicle prices are still rising, semiconductor prices (semiconductors are the key new vehicle supply bottleneck) appear to have peaked and vehicle production levels appear to have largely recovered to pre-COVID levels. We anticipate a gradual easing in automotive price growth as the backlog in demand is cleared. It should be noted that a clearing of this order bank backlog is yet to be seen in the data.

Automotive Supply Chain Indicators

Supply Chain Disruption

Supply chains have been disrupted as a function of COVID-induced lockdowns, elevated demand and transport congestion. We think it is reasonable to anticipate that both the lower production and elevated demand for goods as a result of COVID-induced lockdowns will continue to normalise over time. Shipping container rates, which rose exponentially at the start of the pandemic, are now dropping sharply from their September 2021 peak. New shipping supply, China’s gradual reduction in lockdown restrictions and a slowing of US consumer demand in certain categories are probable contributors to this drop.

Drewry WCI Composite Container Freight Rate (USD per 40-Foot Box)

Housing

Housing, or “shelter”, is a large component of the CPI basket in the US and therefore warrants a mention. The majority (74%) of housing’s CPI weighting is derived from a measure of implied rent called “Owners’ Equivalent Rent”, a survey taken over time of what property owners believe their property would rent for if offered to the market. It is very difficult to assess what drives this measure. Therefore, there is a chance that despite declines in inflation in other categories, this survey, along with potential increases in actual rental costs (22.5% of housing costs), continue to rise and sustain inflation at higher levels. Whilst this could be a factor in the near term, offsetting falls in other inflation components, over the medium term it would appear unlikely to continue if house prices were to decline in response to rising rates, a reasonable assumption, and in an environment where the cost of replacement housing was falling.

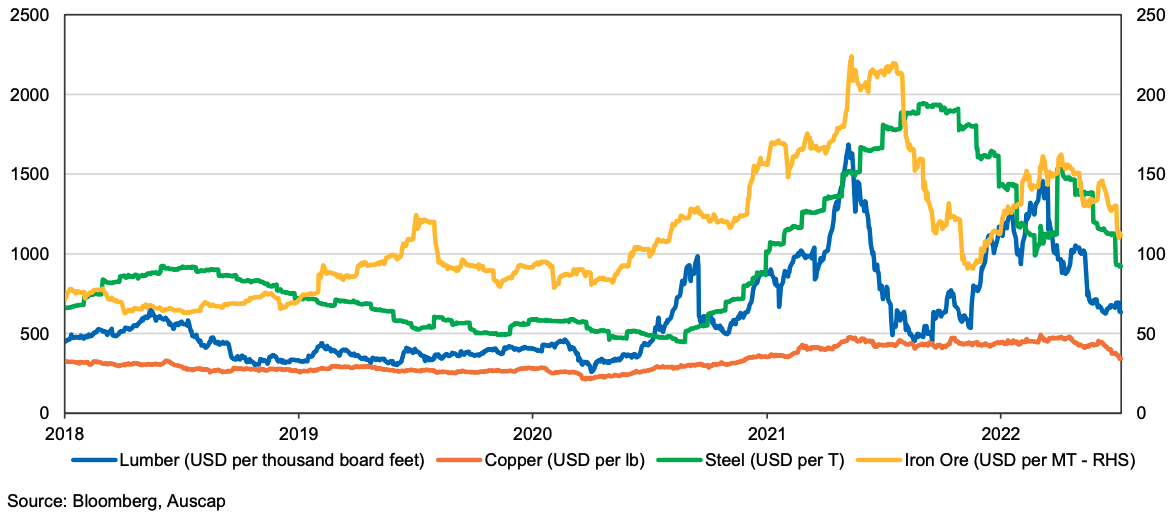

Inflationary forces in relation to the cost of housing construction, whilst not having a large direct CPI impact, affect the cost of meeting new demand for residential property. In late 2021 and early 2022 many construction materials increased in price substantially, but since then much of this price pressure has abated.

Hard Commodity Prices: 2018 to Present

Monetary Policy Effects

Monetary policy is becoming increasingly restrictive. Quantitative easing is winding down and the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is shrinking. The US Federal Funds Rate has been hiked 150bps at the last three meetings and further aggressive hikes have been flagged. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has raised rates 125bps in its last three meetings. Other major central banks are generally adopting the same approach and asset prices globally have fallen sharply. The likely effect of higher rates is the suppression of demand, which again is likely to reduce the inflationary impulse.

It would appear to us, based on the information above, that it is reasonable to expect that many of the inflationary pressures that are currently driving global inflation are likely to abate over the coming year. This is not premised on forecasting future moves in commodity prices or inflation inputs, but on the fact that current spot prices dictate that inflation is likely to ease meaningfully in the absence of another strong upward move in input prices. For inflation to stay high there would need to be continued steep price rises. This is because inflation measures the year-on-year change in the price of goods and services, not their absolute level. Falling prices actually have a deflationary impact on future inflation levels. Investing is probabilistic, and we will change our views if the facts change, but at this stage much of the inflation we have seen appears likely to subside over time.

We do not mean to suggest that inflation does not pose a significant economic or financial risk. In Australia there has been a considerable lag in inflation and the RBA expects it will peak in the final quarter of 2022 at approximately 7%. We also acknowledge the argument that higher wage claims could drive a “wage-price spiral” and that inflation expectations could be anchored at higher levels. We will continue to monitor the facts and adjust our expectations accordingly. However, we believe it presently appears that while “trimmed mean” inflation will be higher than it has been over the last decade, driven by tight labour markets and hence higher nominal wage growth, it is likely to be well below the current levels being experienced in the US, UK and many other jurisdictions.

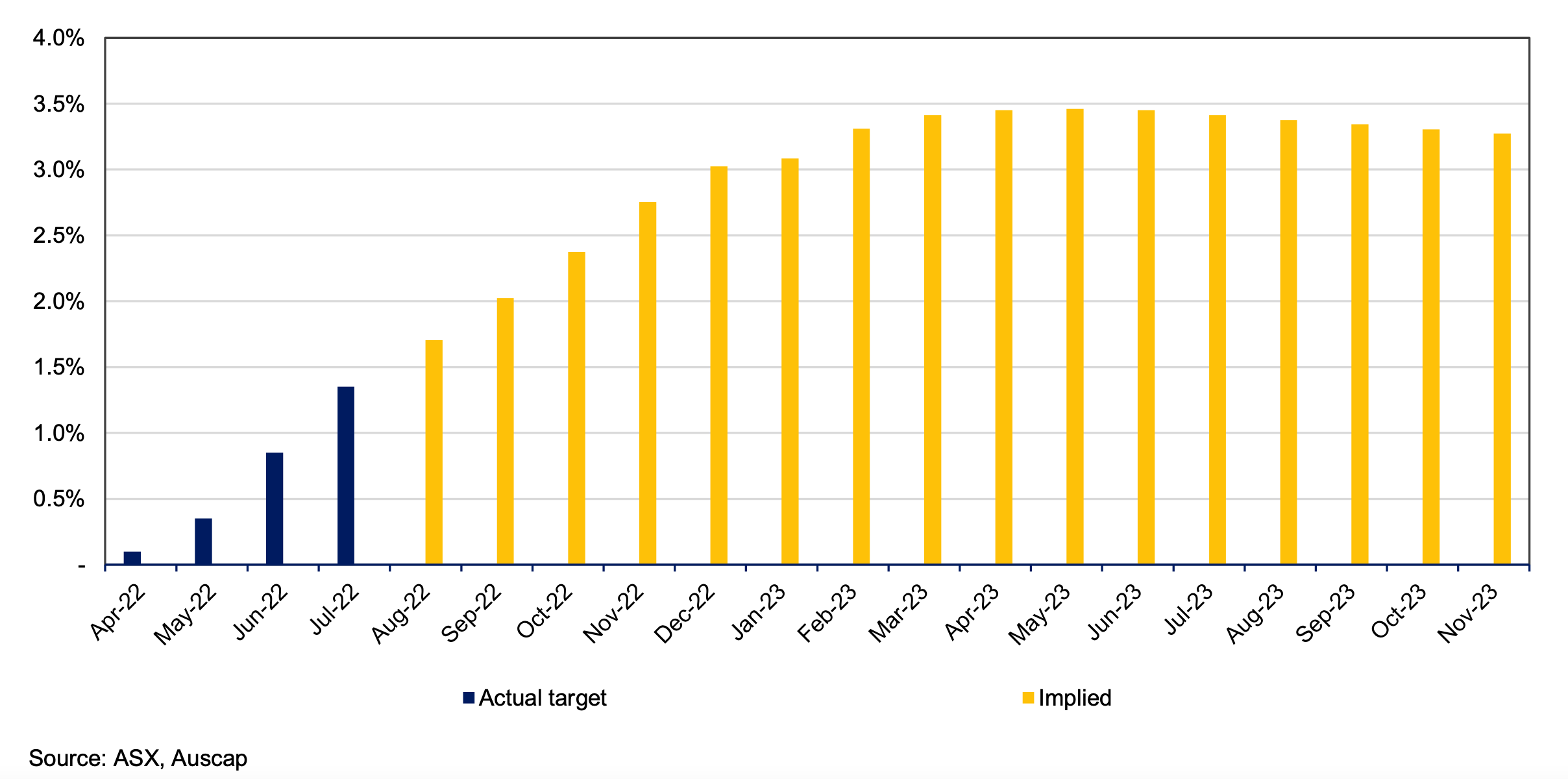

Interest Rates

If inflation subsides then we anticipate that expectations for considerable interest rate increases will moderate. Current futures curves are pricing in considerable interest rate rises.

Interbank Cash Rate Futures Implied Yield Curve (%)

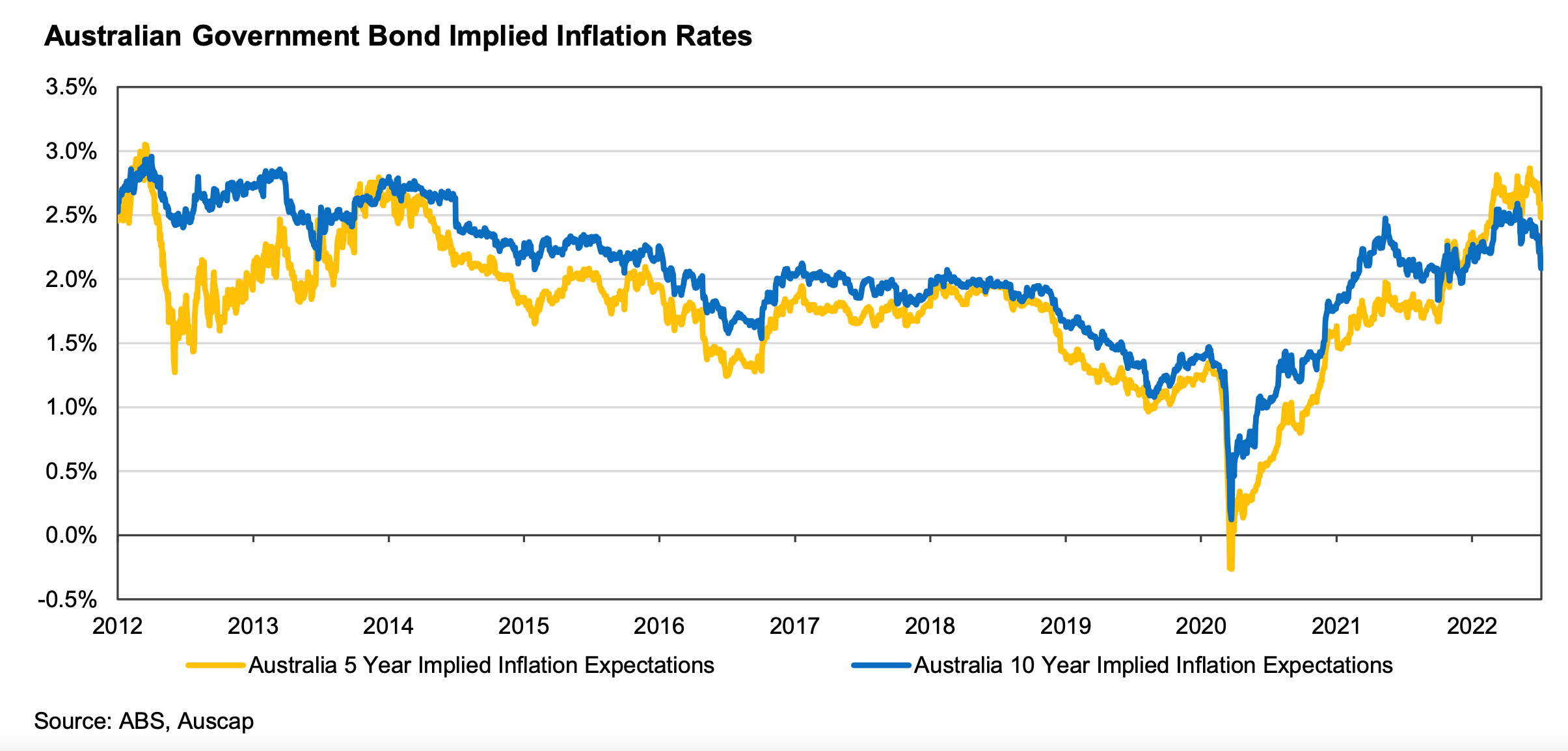

This would appear to be premised on the expectation that inflation will continue to run at elevated levels, albeit 5 and 10 year inflation expectations appear to have moderated recently, and are not reflecting persistently elevated inflation.

If inflation does moderate, then we anticipate that long-term yields on Government bonds might retrace some of their recent upward moves.

Recession Probabilities

If we do end up with significantly higher interest rates, will that automatically result in a recession? Higher interest rates are likely to reduce the amount households and investors are able to borrow. If this eventuates then we think it is almost certain that residential property prices will decline. We witnessed this from 2017 to 2019, when APRA-imposed lending restrictions resulted in a reduction in the availability of credit. Property markets subsequently declined between 10% to 15% in the major Australian capital cities.

The market appears to be pricing in a significant probability of persistent inflation, the risk of much higher interest rates, and the assumption that this will have a negative impact on household expenditure, demand and hence economic growth. There is plenty of talk of a recession, and many stocks, in particular those companies exposed to discretionary household spend, are being priced as though this outcome is inevitable. Yet to us, on the balance of probabilities, this still appears to be a left tail risk event. In this context, we use the term “recession” in the sense of a general decline in economic activity, rather than in a technical sense, where real GDP growth is negative because inflation spikes above nominal GDP growth over a few consecutive quarters. The prospect of a technical recession appears far more likely to us than an ongoing damaging recession.

Would you like to hear from me whenever I publish?

I am the Principal and Portfolio Manager of the Auscap Long Short Australian Equities Fund which targets solid absolute risk-adjusted returns, looking to invest in companies that generate strong cash flows and are trading at attractive prices. If you would like first access to my insights please click on my profile here and hit follow.

3 topics

1 fund mentioned

1 contributor mentioned