Recession versus “goldilocks”: 5 reasons why we could still avoid recession

The case for a recession

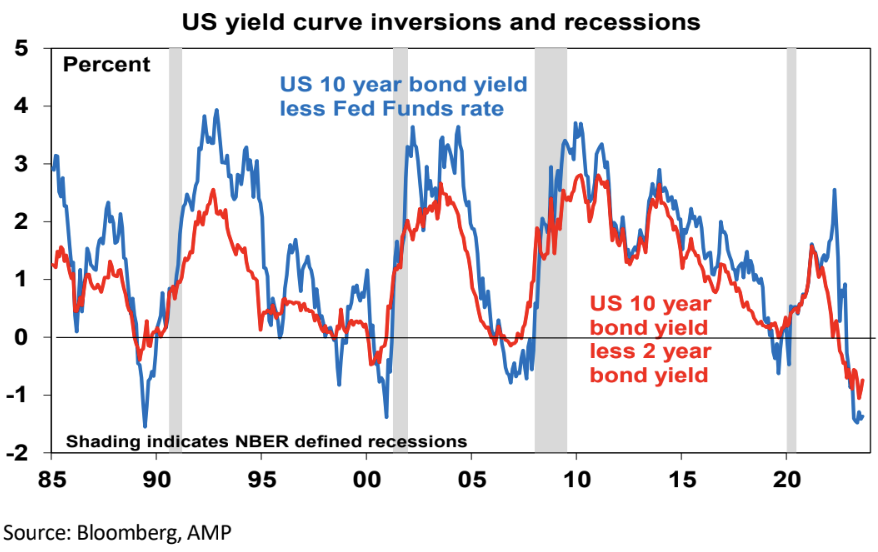

- The US yield curve started to invert, with short term interest rates rising above long-term rates, last year. And this has preceded all US recessions over the last 60 years.

- Leading economic indexes – which combine things like building permits and confidence – are at levels that often precede recession.

- Monetary conditions as measured by bank lending standards have tightened significantly and this normally leads to a collapse in lending.

Can recession be avoided?

- The lag from yield curve inversion in the US can be 18 months. Various versions of it first inverted between July last year and January this year. So given normal lags, it may not eventuate until next year.

- More positively though US yield curve inversions have given false signals in the past, eg, in 1998.

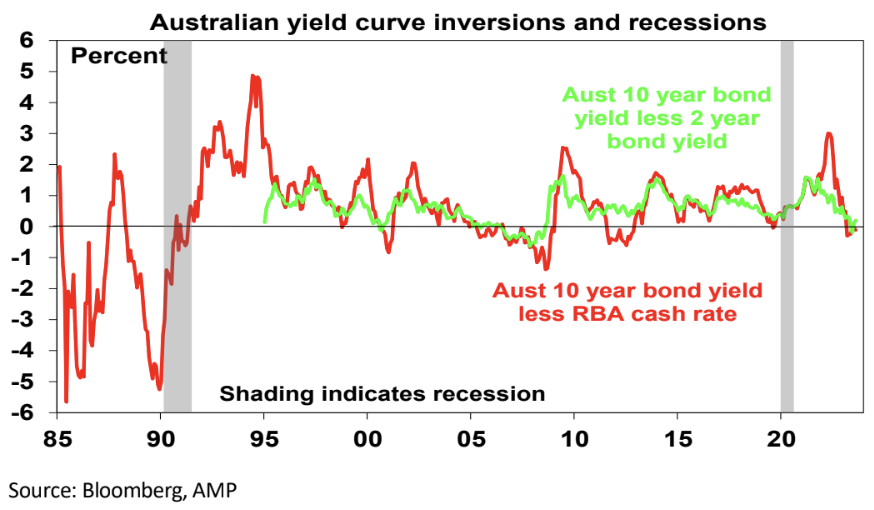

- Inverted yields curves have been a poor indicator of recession since 1991 in Australia and right now it’s not decisively inverted anyway.

First, inflation could fall fast taking pressure off rates

In other words, today’s low unemployment levels could turn out to be consistent with “full employment” and only a marginal cooling in demand may be necessary to return labour and product markets to balance. And so central banks may soon be able to move towards lowering interest rates.

Recently the news on this has been good. US inflation has fallen from a peak of 9% y/y to 3% and Australian inflation has fallen from 8% y/y to 6%. And this has occurred without a rise in unemployment. Our US and Australian Pipeline Inflation Indicators continue to point down. However, there are several reasons to be cautious here.

- First, services price inflation may prove a bit sticky as in some countries wages growth is still picking up. This is clearly a risk in Australia with a faster rise in minimum and award wages this year resulting in a renewed surge in labour costs in the latest NAB survey.

- Second, AI will take years to enhance productivity growth.

- Third, it assumes that central banks can fine tune the economic cycle - the RBA has done this well in the post 1991 period but the Fed not so well. This is made hard by lags in the way monetary policy impacts the economy which risks central banks raising rates too much. Having lost credibility last year in assuming inflation was “transitory”, central banks are likely to err on the side of caution to make sure the inflation dragon is back in its cave before easing up. And of course, this time around RBA tightening has been faster than at any time since the 1980s and household ratios are three times higher now.

Second, there is a lack of excess to unwind

However, this time around beyond the problem with inflation there are little in the way of similar excesses: there has been no business investment boom; there has been no home building boom and housing vacancy rates are low; household debt has fallen from its pre-GFC high; and inventory to sales ratios are low. So given the absence of excess, recession may be avoided or if not it’s likely to be mild.

It’s similar in Australia with the exception that household debt to income ratios are nearly double US levels leaving the Australian household sector as an obvious increased source of recession risk here – particularly with household debt servicing costs now pushing around record levels.

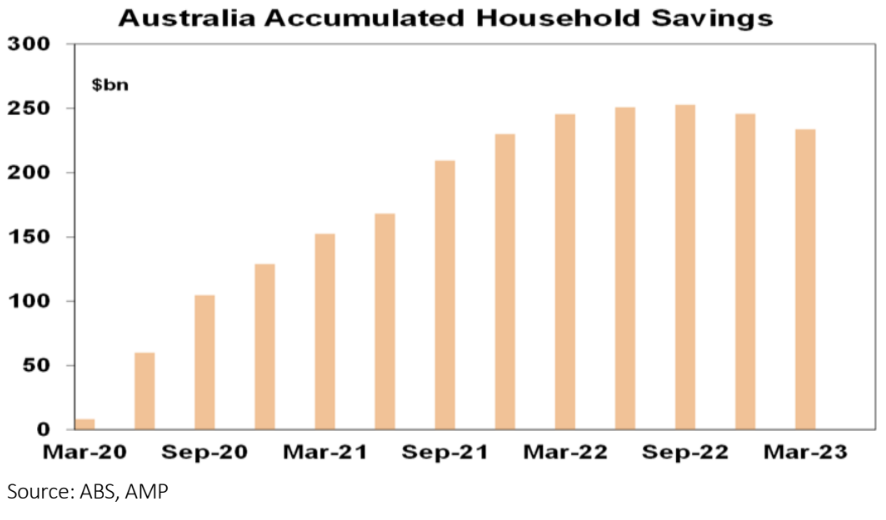

Third, households still have pandemic savings buffers

In Australia it has been run down but remains high at around $230 billion. My concern has been and remains that it is not distributed equally and that for many younger (25-45 year old) households with high debt levels it has been rundown such that it’s no longer of any support in the face of the surge in interest payments. And for older households they are unlikely to use much of it for spending anyway. Nevertheless, at an average level it is a source of support that wasn’t around prior to past downturns.

Fourth, we could have rolling sectoral recessions

Something like this happened through the 1990s and 2000s to varying degrees providing support for the view that the environment back then was characterised by micro instability but overall macro stability and hence milder economic cycles.

In the US, in this cycle home building and technology, and more recently manufacturing, have arguably already had recessions but they are now starting to find a floor so if consumer spending on services turns down it may be offset by an improvement in home building, technology and manufacturing.

Similarly in Australia, home building and retailing have been in recession for a while and conceivably could start to recover as consumer spending on services top out. So far so good but the risk is high that currently weaker sectors don’t recover in time to offset weakness in lagging sectors like services.

Finally, strong population growth may mask recession

In this regard, it’s notable that while both the Australian Government and RBA are forecasting positive GDP growth this financial year on a year average basis at 1.5% and 1% respectively, this is expected to be below the rate of population growth at around 1.7% or more which means that both are forecasting a per capita (or per person) recession, but this is masked by strong population growth.

Of course, what matters for living standards is per capita GDP growth but arguably for investors overall growth is more important as this is what will drive company profits.

Bottom line

But what if growth is too strong?

This has been concerning investment markets in the last week or two with bond yields rising which has in turn has pressured share markets as higher bond yields make investment in shares look less attractive.

This in turn has been made worse by:

- Japan taking another mini step towards removing its ultra easy monetary policy and allowing a further rise in its bond yields which in time may reduce Japanese investment in US/global bonds; and

- Fitch’s downgrade of US debt which has refocused attention on US’ high public debt and worsening budget deficit.