Reserve Bank's inflation challenge

Champagne or water? Excess or temperance?

That’s the question posed this week.

10 basis points.

That’s all it took.

US inflation came in 10 basis points lower than expected on Wednesday.

Stocks surged. Champagne flowed.

Following the US CPI release, US 10-Year bond yields fell nearly 20 basis points. The biggest one-day fall since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

But a 0.1% inflation ‘beat’ is not comparable to the genuine fright caused by SVB’s collapse.

There’s a technical term for Wednesday’s rally.

Kneejerk reaction.

The champagne didn’t flow for long. The rally, much like the drink, lost its fizz. Since Wednesday, the S&P 500 is flat. Aussie stocks are down.

Wednesday’s jubilance is today’s hangover. In markets, temperance is cool.

As for the latest episode of What’s Not Priced In, Greg Canavan and I discuss:

- Whether or not the US inflation data is significant

- Australia’s historic wages growth and what it means for interest rates

- Valuations of the Big Four banks (they look cheap, but there’s more to it)

- Outlook for cashed up Aussie gold miners

- Unappreciated insights from the RBA’s latest Statement

- High mortgage repayments don’t tell the whole story

- Accumulated savings offsetting RBA’s rate hikes

RBA’s ‘last mile’ will be a slog

I want to talk about the Reserve Bank’s inflation challenge.

In my view, taming inflation will be harder than markets think.

Inflation’s ‘last mile’ will be a slog. For a few reasons.

One of them is wages growth.

This week, the ABS released the latest Wage Price Index data.

The WPI rose 1.3% in the September quarter and 4% for the year. The ABS said it was the highest quarterly growth in the 26-year history of the WPI.

The annual growth was the highest since March, 2009.

The data didn’t faze the market upon release. But I wonder if it’ll phase the RBA.

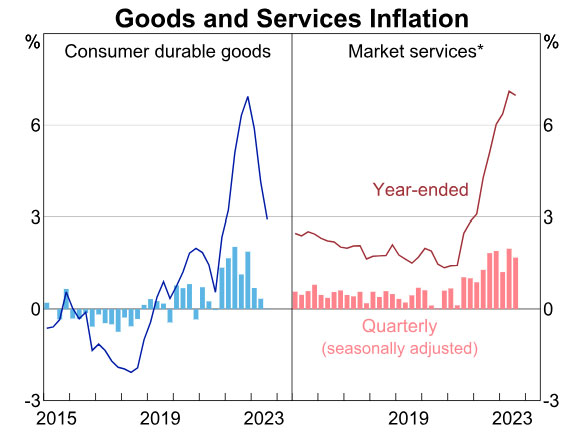

Services inflation is the bank’s bugbear. It’s stickier than officials predicted.

And rising wages play a big role in that stickiness.

Now, high wages growth is fine if productivity is high, too. But Australia’s productivity is poor.

In the latest Statement, the RBA said:

Even so, the cost of labour for firms also depends on growth in labour productivity, which has been very weak. As a result, growth in the cost of labour is very high and is adding to firms’ overall cost pressures; the forecasts assume that productivity growth will pick up, which will be needed for labour cost growth to be consistent with the inflation target.

But what if productivity doesn’t pick up? The RBA’s forecasts were wrong before.

I think wages growth remaining high is more likely than productivity suddenly improving. Even the RBA expects wages growth to decline slower than overall inflation.

Mortgage repayments rising, but overall debt servicing low

Another challenge for the RBA is mortgage repayments.

But not for obvious reasons.

Mortgage repayments are at record highs relative to disposable income. That dents aggregate demand.

Maybe not as much as the RBA would like.

In the latest Statement on Monetary Policy, the Reserve Bank said scheduled mortgage payments rose to ~10% of household disposable income in the September quarter.

But…

It also noted Australia’s stock of personal debt fell ‘substantially’ in the last 15 years.

The overall debt servicing burden for households ‘appears to be lower than in 2008’.

Interesting.

And who knows, maybe households are more comfortable with higher mortgage repayments because their other debt burdens are at multi-decade lows.

Population growth

Another challenge is population growth. Or, population growth outpacing supply.

I’m seeing more editorials in the financial press worrying about this.

Future Fund chairman Peter Costello said earlier this week:

Australia has always been a migrant country, and I’ve always supported immigration. But the levels of immigration now are extremely high.

Population growth is certainly straining housing supply. Rents are rising. So, too, are house prices.

The supply of housing is less flexible than the ‘supply’ of people.

But the Reserve Bank is less concerned.

In the Statement, the RBA pointed out that more people equals more demand and more supply:

Population growth has been substantially stronger than expected following the reopening of the border. However, the net effects on the aggregate inflation outlook and the unemployment rate have been relatively small… The increase in population has added to both aggregate supply and aggregate demand in the economy.

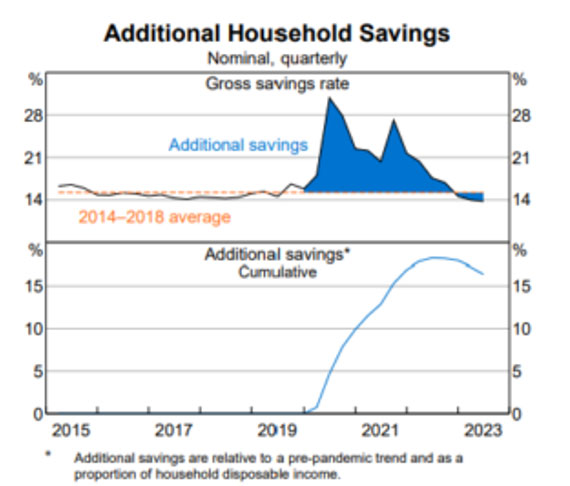

Accumulated household savings

Yet another challenge for the RBA is our savings.

Inflation’s intransigence stumped many.

But the chart below may explain why.

We accumulated enormous savings during the pandemic.

For many, these additional savings — savings above what you’d expect prior to the pandemic — still remain.

Fat tail risk: un-anchored inflation expectations

Where do you think inflation will be in 2024 and 2025?

Our opinions about future inflation matter.

And the Reserve Bank knows they matter.

Our inflation predictions influence the present. Anticipating inflation tomorrow, we can bring about inflation today.

That’s why managing expectations is a big part of the RBA’s job description.

So here’s the Bank's final challenge. A fat tail risk. Unlikely, but worth considering…

Inflation expectations unmooring.

The RBA described this scenario a while back:

But if the inflation psychology of households and firms shifts and inflation expectations move away from the central bank’s inflation target (i.e. they become ‘unanchored’), a period of higher inflation will become persistent because households and firms will expect inflation to be higher in the future and adjust their behaviour accordingly. Consequently, it is much easier for a central bank to manage inflation if inflation expectations are anchored rather than unanchored.

If markets want rates to fall, they better wish our inflation expectations remain anchored.

Yet the risk of expectations unanchoring, while not worrisome now, is rising.

And it will keep rising with each missed inflation forecast by the RBA.

The latest Statement was riddled with admissions inflation continues to surprise Bank officials.

This Monday, RBA’s acting assistant governor Marion Kohler made another.

The next stage in bringing inflation down to the RBA’s target is ‘likely to be more drawn out than the first’.

The ‘road ahead could be bumpy’.

And of the ‘key risks’ Kohler identified was inflation expectations untethering. Kohler said:

One of the key risks is the possibility that high inflation today could lead households and businesses to expect high inflation in the future, putting upwards pressure on actual prices and wages. Encouragingly, measures of medium-term inflation expectations have generally remained consistent with the Bank’s inflation target. But, if high inflation did become entrenched in people’s expectations, it would be very costly to unwind, involving even higher interest rates and a larger rise in unemployment.

A risk to monitor.

5 topics

5 stocks mentioned

1 contributor mentioned

.png)

.png)