Reversing the 'great easing': what lies ahead for central banks

The outlook over the next two years is not without risk. There will always be uncertainties in investing, from bouts of geo-political tension and financial hazards, to fears of new virus strains and sticky inflation. Indeed, over the remainder of this year, challenges from the US debt ceiling debate, China’s property sector slowdown, and global supply-chain pressures adding to near-term temporary inflation spikes will all likely weigh on risk appetite.

But as we approach 2022, the worst of the pandemic-led 2020 recession is likely behind us. Vaccination rollouts are progressing both in Australia and offshore. According to UBS, its “current year-end projection is that the emerging market vaccination share will be at 71%, developed market at 80% and the population-weighted global total at 72%”. And while we’ve discussed at length the passing of ‘peak growth’ — and markets will at times continue to stress about this — 2022 looks set to be a year of healthy global growth. The persistence of the global growth recovery in 2022 is being supported by several key drivers:

- Rapidly improving jobs markets as mobility restrictions are eased globally. Particularly reflecting pent-up demand for out-of- home services spending, this should boost employment and support consumer income. For example, in the US, job openings are at a record high (and exceed the total pool of unemployed by 1 million), while in Australia, ANZ job ads have recently eased, but are still 26% above pre-pandemic levels.

- Household balance sheets are flush with cash, with high savings rates giving consumers significant buying power. Significant government income support over the past year and virus caution have combined to leave saving rates well above normal in most developed economies. While uncertainty may persist as economies open, consumers will have significant pent-up demand, and the ability to satisfy it as 2021 ends.

- Strong production will drive activity and income as suppliers rebuild low inventory levels across the world. Businesses’ current low level of inventories due to supply-chain disruptions should see a surge in new orders to meet current demand and then also return stocks to normal. Most importantly, the global shift of inventory management from ‘just in time’ (where stocks are kept at a minimum) to ‘just in case’ (holding large stockpiles to minimise risks of supply-outs) should also drive production.

Estimates for 2022 world growth continue to be buoyant, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasting 4.9% and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) forecasting 4.0%, strong growth in the wake of 2021’s likely near 6.0% pace (a 40-year high).

Strong growth ahead, but policy becoming ‘less easy’

It is with that backdrop that the period ahead is going to be one where policy turns less stimulatory.

Markets are likely to focus less on the tightening of fiscal policy. But 2022 is, nonetheless, a year where the fiscal impulse turns from a tailwind to a headwind, as governments globally begin the long, likely multi-decade, journey of repairing their balance sheets. According to UBS, after a record-breaking 4.0% (of global output) fiscal stimulus in 2020, an insignificant -0.3% fiscal headwind in 2021 becomes -2.4% headwind in 2022.

Three factors probably mitigate this impact:

- Most of the adjustment is in the US and it’s largely timing. The front-loading of income support in first-quarter 2021 means the recorded 2022 impact is actually unfolding in second-half 2021. Outside the US, 2022’s global fiscal drag is more like 1%.

- Less pandemic income support for many will largely be offset by high saving balances.

- Fiscal sentiment is likely to be buoyed by new US infrastructure packages from 2022 before end-year. An expected first-half 2022 federal election in Australia is also likely to underpin additional fiscal support domestically.

Markets will intently focus on the tightening of monetary policy — in particular, the outlook through 2022 for the removal of quantitative easing (mostly bond buying) and any actual increase of central bank policy rates. As always, the path of inflation will be key in determining the urgency with which central banks respond. Here, recent data supports banks’ views that near-term inflation is being elevated by short-term supply-chain pressures (and base effects) and a structural inflation uplift is not immediately upon us.

Moreover, central banks have a strong incentive not to prematurely derail the recovery. Many central banks — including the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) — have openly shifted their reaction function from pre-emptive to re-active. In other words, they have committed to not lift rates until inflation is sustainably within their target ranges. As discussed below, this is leading to significant global phasing of policy moves.

Further, many central banks — including the RBA and European Central Bank (ECB) — are acutely aware they have underperformed their inflation target for the past five to 10 years and would likely be keen not to repeat the outcome, giving them scope to be slower than normal to respond. Their colleagues on fiscal policy are also likely to prefer moderate (rather than low) inflation to boost wages and company revenues and aid the repair of budget positions.

Who are the hawks? Who are the doves?

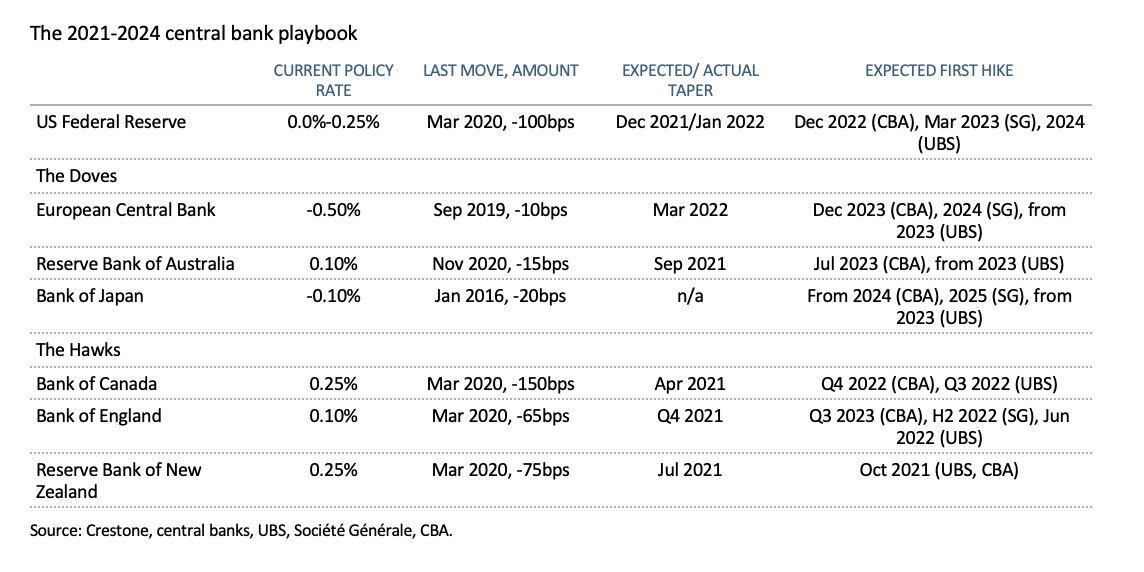

The Fed is widely viewed as the global setter of interest rates. And like the Fed, most developed economy central banks have rates set close to zero. Looking ahead, the Fed is surrounded by some central banks that are more hawkish, as well as some that are more dovish. See the table below.

The Fed — the global rate setter

- In September there was a hawkish shift as the Fed left monetary policy unchanged as expected. But the accompanying statement, as well as the post-meeting presser by Chair Jerome Powell, shifted more hawkishly regarding the timing of hikes and the pace at which the Fed will wind down its bond-buying (or tapering) program.

- Tapering is expected from December 2021. It is now consensus that the Fed will detail its taper at its 3 November meeting and start tapering at the December (or possibly January 2022) meeting. Further, the Fed clearly signalled an intent to finish by mid-2022, implying the current $120 billion per month program will be cut by about $15 billion per month.

- There is no consensus on Fed rate hikes. In September, the quarterly ‘dot plot’ (which shows Fed members’ forecasts) was evenly split between a first hike in 2022 and 2023. A similar split exists between analysts. CBA sees the first hike in December 2022, driven by a ‘sticky’ inflation view, while UBS believes easing inflation in 2022 will drive a dovish tilt, pushing out a hike until 2024. Société Générale (SG) is in the middle at March 2023.

The doves signalling a slower pace than the Fed

- The ECB has not lifted its cash rate since 2011, and there is little expectation of a move before 2024. Most focus is on the tapering of its two bond-buying programs: the pre-pandemic program (APP) and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP). The ECB has signalled it will discuss the PEPP at its December 2021 meeting, with consensus focused on that program finishing on time at end-March 2022. However, as Société Générale notes, “President Lagarde let it slip that she saw it unlikely that the ECB would be able to taper QE (quantitative easing) in tandem with the Fed”, given the more advanced position of the US recovery. This suggests the ECB may boost the APP when the PEPP expires, continuing its significant bond-buying.

- Australia’s cash rate was reduced to 0.1% in November 2020. At its September meeting, the RBA continued its planned tapering from $5 billion to $4 billion per month. However, it delayed further potential reductions from November to February 2022. UBS expects a further reduction to $3 billion in February 2022 before the program ends in May 2022. But that appears to be where the stimulus reduction ends. In a mid-September speech, RBA Governor Lowe argued the current market pricing for a higher 0.6% cash rate by end-2023 was "difficult to understand", sticking to his April 2024 “at the earliest” prose. UBS sees the first RBA hike beyond end-2022, while CBA sees the first hike to 0.5% in mid-2023.

- The Bank of Japan was the first major bank to cut rates to zero in 1999. After reaching the heady heights of 0.5% in 2007, it cut to -0.1% in 2016, where it is today. CBA expects no change until at least 2023 (its horizon) and Société Générale sees 2025 as a “likely starting point”. The Bank of Japan did introduce special measures in response to the pandemic, mainly targeting corporate lending. These are likely to be terminated in March 2022, with a timing for the tightening of policy due in December or January next year. This aside, the bank is seen maintaining its uber-dovish stance, given entrenched low inflation, for years to come.

The hawks signalling a faster pace than the Fed

A range of central banks have already beaten the Fed out of the blocks and raised rates. Many of them sit in the emerging markets, where central banks have less ability to tolerate rising inflation or have faced increasing concerns about financial stability. Over recent months, there have been rate hikes in Korea, Brazil, Russia, and Hungary. In September, Norway’s central bank became the first developed market bank to hike, with another hike likely in December, according to BCA Research.

- The Bank of Canada, one of the first banks to announce tapering in April 2021, is expected to signal further tapering at its October meeting, cutting its bond-buying from $2 billion to $1 billion per week. It is widely expected to finish this year. However, Governor Tiff Macklem, like Fed Chair Powell, has emphasised that the end of bond-buying and the start of the hiking cycle are two separate decisions. UBS expects the Bank of Canada to start hiking from July 2022, while CBA forecasts fourth-quarter 2022.

- The Bank of England, at its September meeting, kept the policy rate unchanged at 0.1%. But according to UBS, “the BoE appears to have turned more hawkish”, with two dissenters voting for reduced bond buying (currently GBP 3.4 billion per week). Indeed, the Bank of England's bond program (GBP 875 billion in total) has already been tapered and is expected to be complete before end-year. The bank also noted the case for modest tightening over the medium term had been strengthened. Both UBS and Société Générale see the first interest rate hike mid-2022.

- The Reserve Bank of New Zealand is widely seen as the next most likely to follow the Norges Bank, despite having also whipped the market into a frenzy with speculation of negative rates at the height of the pandemic. Markets are priced for a 0.25% hike on 6 October (to 0.50%) and UBS sees rates rising to 1.5% by August 2022, with further 0.25% hikes every quarter from here.

The outlook for bonds and currencies

Latest estimates suggest global central banks are moving slowly, not inconsistent with their recent rhetoric regarding taking a more reactive, rather than pre-emptive, approach to inflation. Indeed, while there are a few key developed market central banks likely to begin lifting rates during 2022 (the hawks, namely the Bank of England, Bank of Canada and Reserve Bank of New Zealand) from a starting point near-zero in 2021, policy rates on average seem unlikely to exceed 1% before 2024.

Of course, while policy interest rates are likely to remain very low, most central banks are positioning or have already begun to wind back their stimulus via bond-buying during the next 12 months. The impact of this on bond yields is uncertain. On the one hand, the improved growth outlook should lead to higher bond yields. However, on the other, in 2013, concerns central banks were moving too quickly saw bond yields retrace lower.

On this outlook, monetary policy remains historically accommodative for an extended period of time. This is likely to underpin both economic and asset price growth in the next couple of years and provide a very supportive backdrop for risk assets, particularly housing and equity prices.

Such an outlook is likely to continue to see unemployment rates fall over time, potentially to levels that should lift wages growth and eventually inflation (potentially through 2023-24). And if central banks have the courage to hold firm to their promise to hold fire until inflation is sustainably above target, inflation expectations and longer-term bond yields are likely to continue to grind higher (and curves trend steeper) in the period ahead.

This environment is one consistent with positioning portfolios moderately overweight equities relative to fixed income, while continuing to build exposure in unlisted (including defensive) alternative assets that are likely to be impacted less if inflation proves a challenge for risk appetite in the future.

Recent weeks have seen the accumulation of central bank tapering news — and the potential earlier-than-expected timing for the first Fed rate hike — push US 10-year bond yields from 1.30% to 1.51% in September. Ten-year yields have risen from 0.59% to 1.02% in the UK and -0.42% to -0.20% in Europe over the same period.

We continue to expect 10-year bond yields in the US and Australia to drift higher to a 2.0%-2.5% range in first-half 2022. Thereafter, the balance between bond demand and supply will be important to the future direction as central banks purchase less, but fiscal issuance reduces as budgets trend better post-stimulus. The balance between longer-term disinflationary forces such as demographics and tech disruption, and inflationary forces such as wages growth and ongoing supply-chain rigidities will also be important.

For exchange rates, the clear delineation between central banks that are relatively hawkish and dovish over the coming year suggests the Australian dollar, the euro and the Japanese yen may struggle relative to the UK pound, New Zealand dollar and Canadian dollar.

For the Australian dollar, UBS and CBA target about US$0.80 for end-2022, a 10% rise from here. This is likely to see the domestic currency outperform the euro and the Japanese yen, but less so the British pound, which could rise even faster. That said, we believe recent developments in China suggest risks are skewed to the downside for the Australian dollar.

Learn what Crestone can do for your portfolio

With access to an unrivalled network of strategic partners and specialist investment managers, Crestone Wealth Management offers one of the most comprehensive and global product and service offerings in Australian wealth management. Click 'CONTACT' below to find out more.

4 topics