Rising inflation: A structural shift or dead-cat bounce?

Google searches for “inflation” are higher now than at any time since such things were first measured around 13 years ago. It’s partly a natural reaction to the post-COVID recovery that has been underway, to varying degrees, since news of a successful vaccine first hit the press last November. And it’s also because of the jump in the US consumer price index, which currently sits at 5% according to the latest Fed figures – its highest rate since 2008.

For months, inflation has been the elephant in the room in any financial market forecast, particularly the discussion about whether the rise is a long-term shift or a blip. In the second part of this three-part series, we put that exact question to the trio of macro minds we’ve been quizzing in recent days. They are:

- Damien Klassen, head of investments, Nucleus Wealth;

- Tim Toohey, head of macro and strategy, Yarra Capital Management; and

- John Abernethy, chairman, Clime Investment Management.

“More sources of structural inflation than deflation"

Tim Toohey, Yarra Capital Management

The general consensus in the market is that inflation is transitory, largely because of the highly visible prices of used cars, airline tickets, car rental rates and insurance. Once these prices normalise as COVID eventually passes, inflation fears will also soon pass.

But there is plenty going on beneath the surface that is more concerning.

- Recent US inflation prints aren’t just a little higher, but the biggest in more than 20 years.

- The much-discussed supply chain disruptions are proving difficult to clear.

- Supply chain diversification is inherently inflationary.

- The ability of firms to find suitable labour has been one of the biggest surprises of the pandemic. Given the starting point is a tight labour market at a time when we are likely to see a run of months of strong payroll gains in the US, it is also possible that wages surprise on the upside during the coming quarters.

- Housing costs are the biggest component in the consumer pricing index, specifically rents. With house prices rising rapidly, vacancy rates at very low levels and asking rents rising sharply in recent months, it seems housing costs will soon become the dominant driver of US inflation.

But decarbonisation is perhaps the biggest structural driver of inflation globally, which still looms and is not broadly understood. This push means we’re essentially choosing, for valid reasons, to write off large swathes of our capital stock and replace it with new low carbon-emitting technology.

The heavily Capex and resource-intensive exercise of decarbonisation threatens to keep upward pressure on the prices of both raw materials and skilled labour.

We believe US inflation numbers may well have a 4 in front of them in the coming months, before some easing back towards 2.5% for a couple of quarters. Some might read this to mean inflation will be transitory. But when it’s easier to identify more sources of structural inflation than deflation on the horizon, we caution against expecting the global economy to slip back into a low inflation low volatility environment.

Rampant inflation unlikely

Damien Klassen, Nucleus Wealth

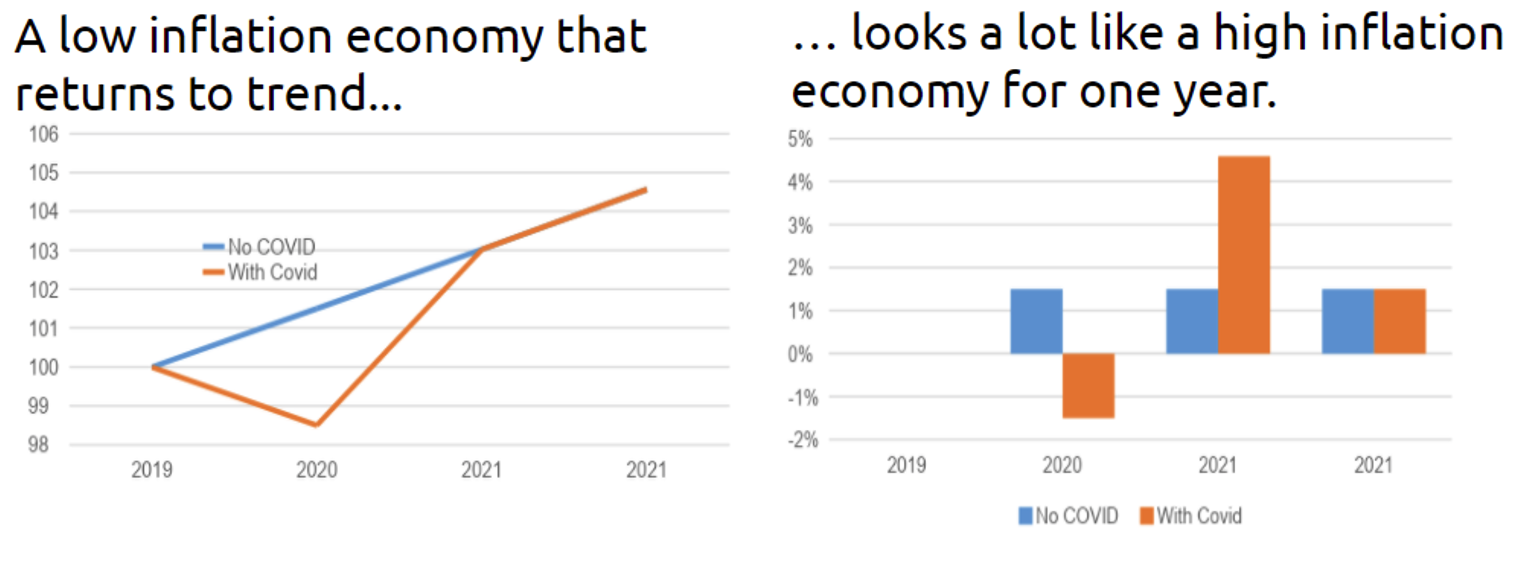

I believe this inflation rise will be transitory. We recently published a four-part series on this topic. In part one, we looked at inflation today not being the same as inflation in the 1970s.

We looked in particular at issues that caused inflation in the 1970s and how the rules have changed since then. This included a discussion of the ways that technology is inherently deflationary. What does this mean? It leads to a financial system over-engineered to prevent inflation.

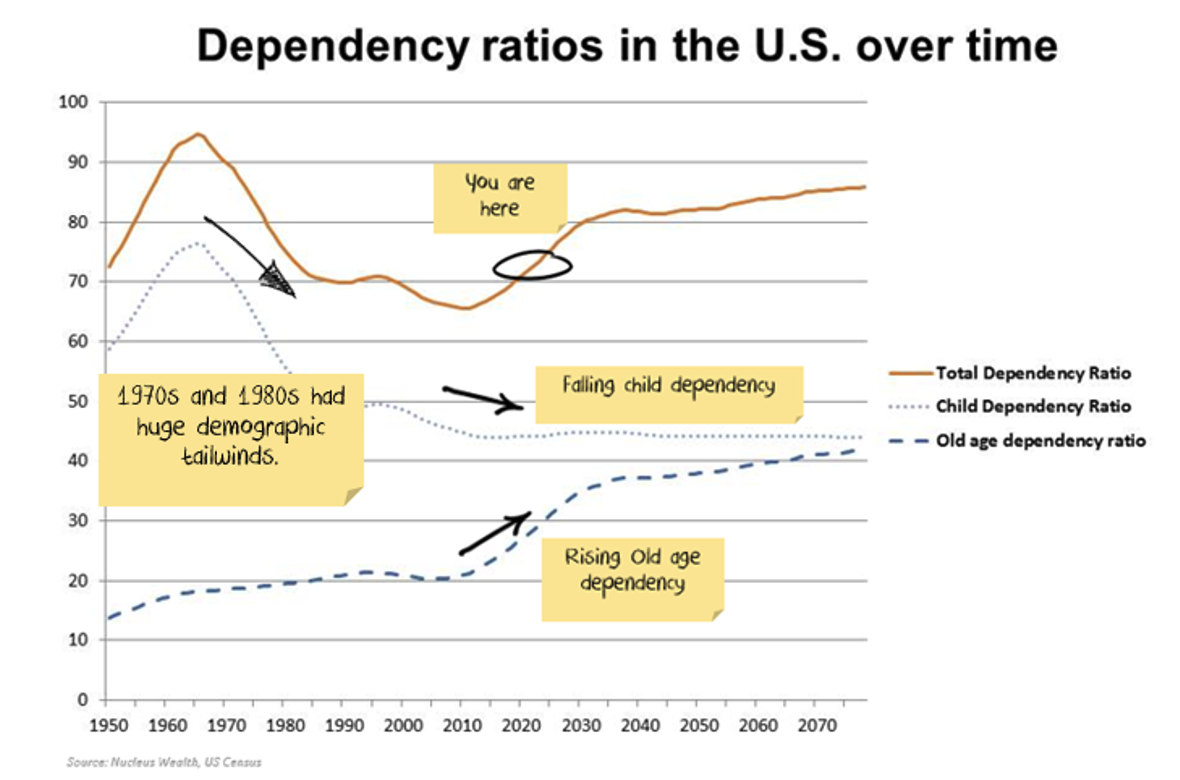

And it took 20 years for inflation expectations to fall, despite persistently low inflation, as we explain by looking at the issues of trade, demographics, debt accumulation and manufacturing. All suggest that inflation will be harder to create.

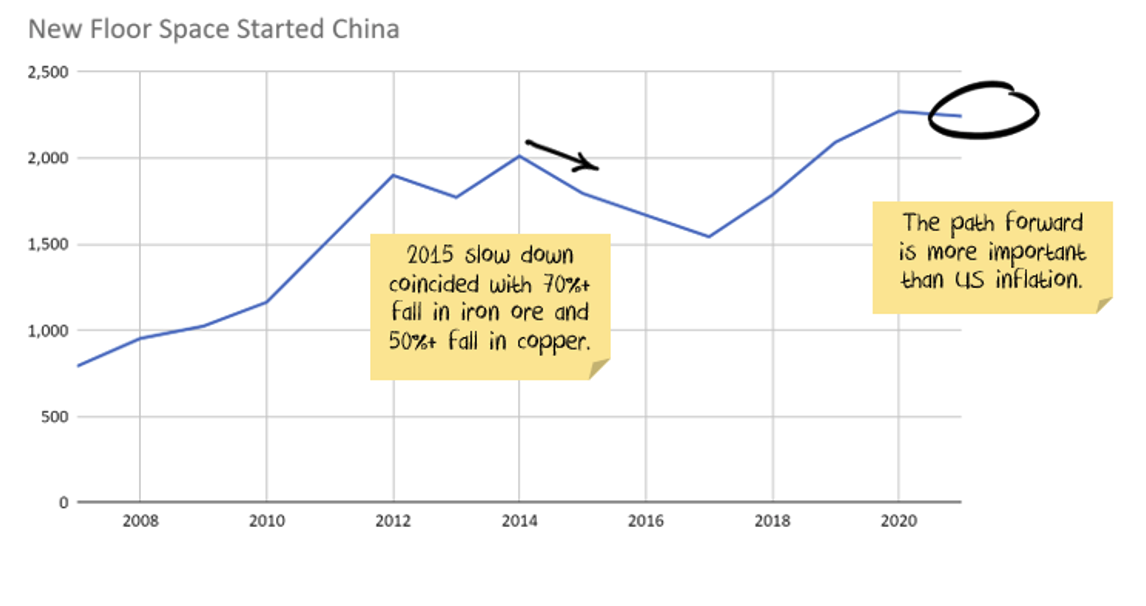

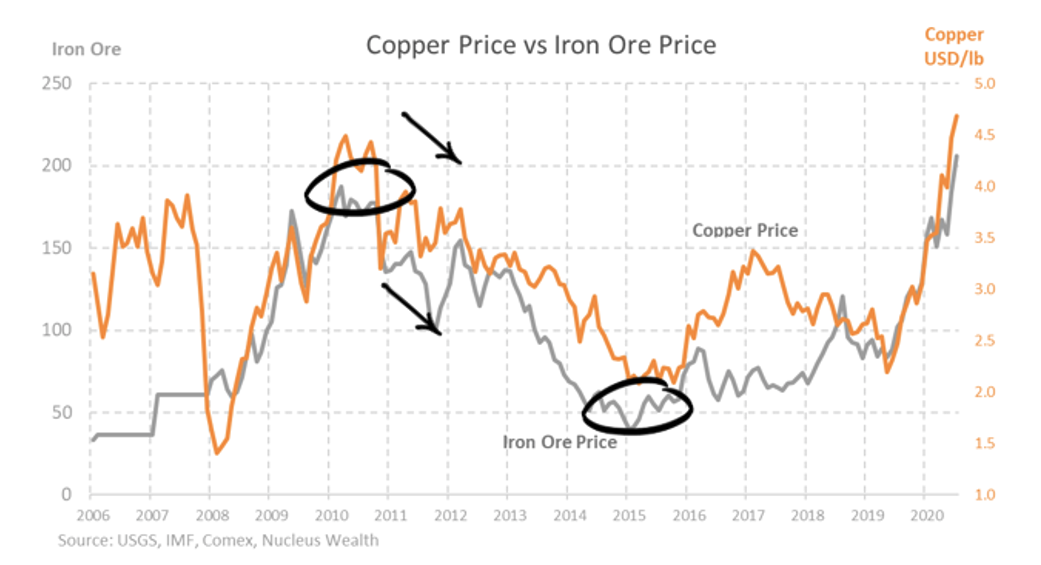

In part two of this earlier series, we approached the China inflation problem, particularly concerning commodity inflation that is linked far more strongly to the nation’s domestic stimulus than stimulus from developed markets. Breaking down the numbers illustrates that a bet on commodity prices is, in effect, a bet on Chinese housing construction. And the signs are ominous.

The inventory supercycle is also key to the changing nature of inflation over the last few decades, disproportionately affecting manufacturers both upwards and downwards. We are in the up-cycle now.

In addition to the usual cycle effects, retail demand has been “juiced” by:

- a mix of stimulus cheques,

- lack of services,

- pent up savings.

Consumers have been spending on goods because they couldn’t spend on services. At the same time, manufacturing supply has been limited by COVID, the Suez Canal blockage and changing demand patterns. But inventory cycles are short. The price signals of today are building the excess capacity of tomorrow. The signs are good for economic growth but are not indicative of rampant inflation.

A quarter-century is a tough trend to end

John Abernethy, Clime Investment Management

The world has been in a significant deflationary cycle for around 25 years.

This cycle has been created and supported by the emergence of China as a massive industrialised economy. As it grew, China replaced western manufacturing at cheaper prices and thereby drove down the prices of many consumer products.

Other deflationary factors have been:

- the enduring technological revolution,

- excess global energy supply and development of alternatives, and

- the excess supply of labour that has resulted.

So the question is – has the big deflationary cycle ended? That will determine if the current pick-up in inflation is transitory or structural. My view is that the big deflation cycle will endure. But I am monitoring the countervailing forces carefully.

The factors that have created it (noted above) will continue. But the maintenance of stimulatory monetary policies definitely support asset price inflation and particularly (as we can see) in the cost of housing, which is essential to the broad community.

If housing cost inflation ultimately requires an adjustment to wages, then transitory inflation will become structural. Wage growth embeds inflation unless it is offset by productivity gains that are mainly driven by technological enhancements and infrastructure investment.

The wrap-up

Again, Nucleus Wealth’s Klassen was the standout among our three respondents. While their overarching view is that inflation is likely to pull back again, both Clime’s Abernethy and Yarra Capital’s Toohey couched their answers more carefully. But Klassen was unequivocal in his one-word opener, “Transitory.” And as in his previous answers, he uses the China example, this time in relation to its resources demand and central role in the commodity supercycle – demand that he believes is looking “ominous”.

Not an existing Livewire subscriber?

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

And you can follow my profile to stay up to date with the rest of this series as it's published. In part one, our contributors outlined which macro forces to focus on in the next year or two; and in part two, our contributors tipped which assets they expect to win (and lose) as massive stimulus unwinds.

4 topics

4 contributors mentioned