Rising interest rates and the banks

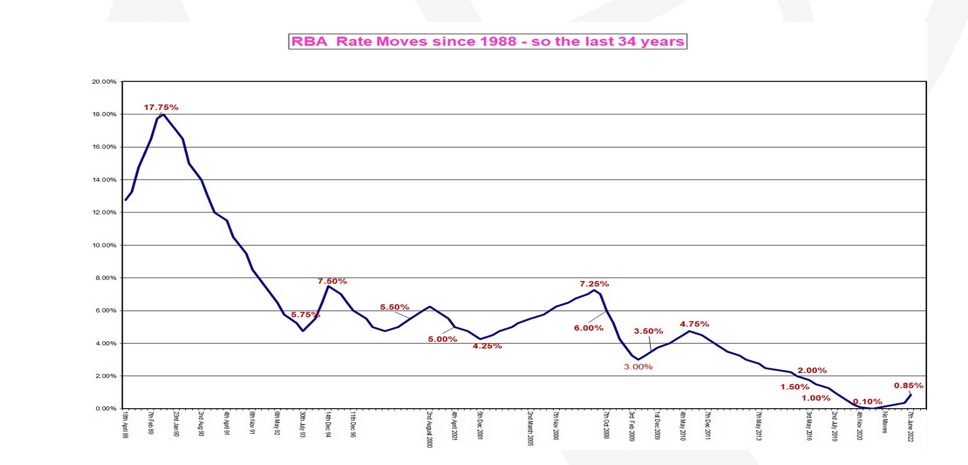

Last Tuesday afternoon, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) surprised the market by lifting rates by 0.50% at their June meeting, taking the cash rate to 0.85%. This surprised many, with the consensus view for a 0.25% hike, with the more significant move indicating the central bank’s determination to attack inflation.

While there has been some angst in the financial press about raising interest rates, this is a sensible move to stop the economy from overheating and tackle inflation. With the unemployment rate at 3.9% (the lowest since 1974), average Australian house prices up 30% since January 2020 and inflation at 5%, it is hard to make the case that the RBA needs to keep rates at ultra-low crisis levels.

In this week's piece, we are going to avoid commenting on the noise that has dominated trading on the ASX over the past ten days and look at how the banks are placed to capitalise on a rising interest rate environment. Since the RBA decision, the major banks’ share prices have fallen on average by -12% based on fears around higher bad debts as well general market malaise impacting the ASX based on rising inflation in the USA. Unlike what has been reported in the press, a rising interest rate environment has historically been beneficial for bank profits, not a negative and loan losses in 2023 are likely to be significantly less than in the early 1990s or 2008-10.

Rising interest rates and expanding profit margins

Rising interest rates have historically seen expanding bank profit margins, as interest rates paid on loans increased immediately. Still, the banks are slow to increase the rates they pay on cash accounts and term deposits. Indeed all the major banks increased variable mortgages by 0.5% within hours of the RBA decision, moving their standard variable rates to around 5.3%, with only minor increases to rates paid on a limited range of term deposits.

Rising interest rates increase the benefits banks get from the billions of dollars held in zero or near-zero interest transaction accounts that can be lent out profitably. In May, Westpac revealed that they have $601 billion in customer deposits (earning between 0% and 0.5%), enough to fund 83% of the bank’s net loan book, which means that the bank doesn’t have to go to the now more expensive wholesale money markets to fund their lending book.

We see that the market is ignoring the impact on bank earnings of the rise in interest rates. Every 0.25% increase in the cash rate expands bank net interest margins by around 0.02%; while this sounds like a small increase, based on a combined loan book of $3 trillion, this is significant. A movement in the cash rate from 0.35% to 1% will see an additional $5 billion of revenue flow to the big 4 Australian banks.

Bad debts will rise, but that is not bad

Rising interest rates will see declining discretionary retail spending as a higher proportion of income is directed towards servicing interest costs. While bad debts will increase, this should be expected.

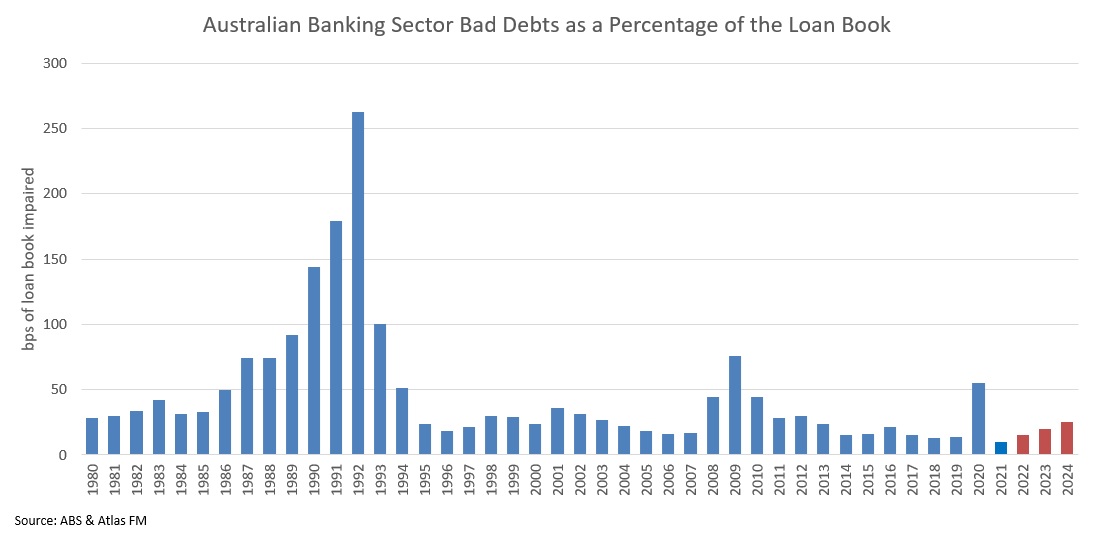

In May 2022, the major banks reported bad debt expenses between 0% and 0.2%, the lowest in history and clearly unsustainable. Excluding the property crash of 1991, bad debt charges through the cycle have averaged 0.3% of gross bank loans for the major banks, with NAB (ASX: NAB) and ANZ (ASX: ANZ) reporting higher bad debts than Westpac (ASX: WBC) and CBA (ASX: CBA) due to their greater exposure to corporate lending.

The 1989-93 spike in bad debts should be excluded, as here, bank bad debts spiked due to a combination of poor lending practices to 1980s entrepreneurs such as Bond and Skase et al., as well as interest rates approaching 20%. In 2022 the composition of Australian bank loan books is considerably different to what they were in the early 1990s or even 2007, with fewer corporate loans and a greater focus on mortgage lending, which is secured against assets and historically has very low loan losses. In any case, bank loans will be priced assuming higher bad debts. In May, NAB noted that their average customer has approximately two years of loan payments in their offset accounts

Well capitalised

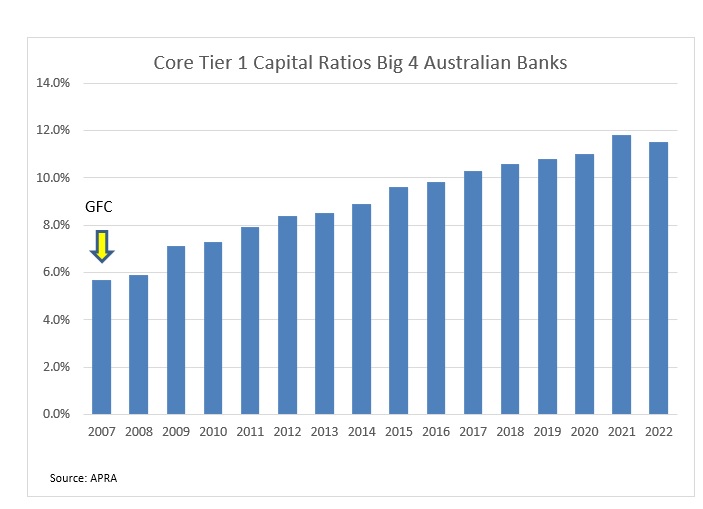

The table below shows that the banks have been building capital, particularly since 2015, when APRA required that the banks have “unquestionably strong and have capital ratios in the top quartile of internationally active banks”. Furthermore, in the lead-up to the Financial Services Royal Commission, the banks have divested their wealth management and insurance businesses to varying degrees. This resulted in the banking sector remaining well capitalised to withstand increases in bad debts, though capital has dipped in 2022 due to share buy-backs conducted by all major banks. Currently, in aggregate, the four major banks retain $15 billion in collective provisions against unknown doubtful debts. This equates to around 0.53% of gross loans, significantly above expected rises in bad debts. This provisioning level should comfort shareholders that the banks are well capitalised, and dividends will be maintained in the medium term.

Our take

The May reporting season showed that Australia’s banks are in good shape and face a better outlook than many sectors of the Australian market. One of the major questions confronting institutional and retail investors alike is the portfolio weighting towards Australian banks in an environment of rising rates.

After the shock of last week’s rate rise has been digested, we expect the banks to outperform in the near future, enjoying a tailwind of a rising interest rate environment and high employment levels, which will see customers make the new higher loan repayments. Additionally, the large domestic banks have much simpler operations in 2022, than the sprawling empires of the early 1990s and 2006, as well as minimal exposure to events in Europe and economic issues in the USA. With an average grossed-up yield of 8% and rising earnings, bank shareholders will be rewarded for their patience and for ignoring the current market noise.

4 stocks mentioned