Saul Eslake: The biggest macro pressures and what they mean for your portfolio

You might be laughing if you hold a stake in the likes of Maersk or the Mediterranean Shipping Company, given the combination of COVID’s supply chain snarls and the vaccine-led reopening have seen such firms reap their biggest payday in more than a decade.

But hauling a container from China to Europe now costs around US$14,500 – up more than 500% year-on-year, according to figures from shipping data firm Clarkson’s Research. Not since the post-GFC boom of 2008 have freight prices hit such levels.

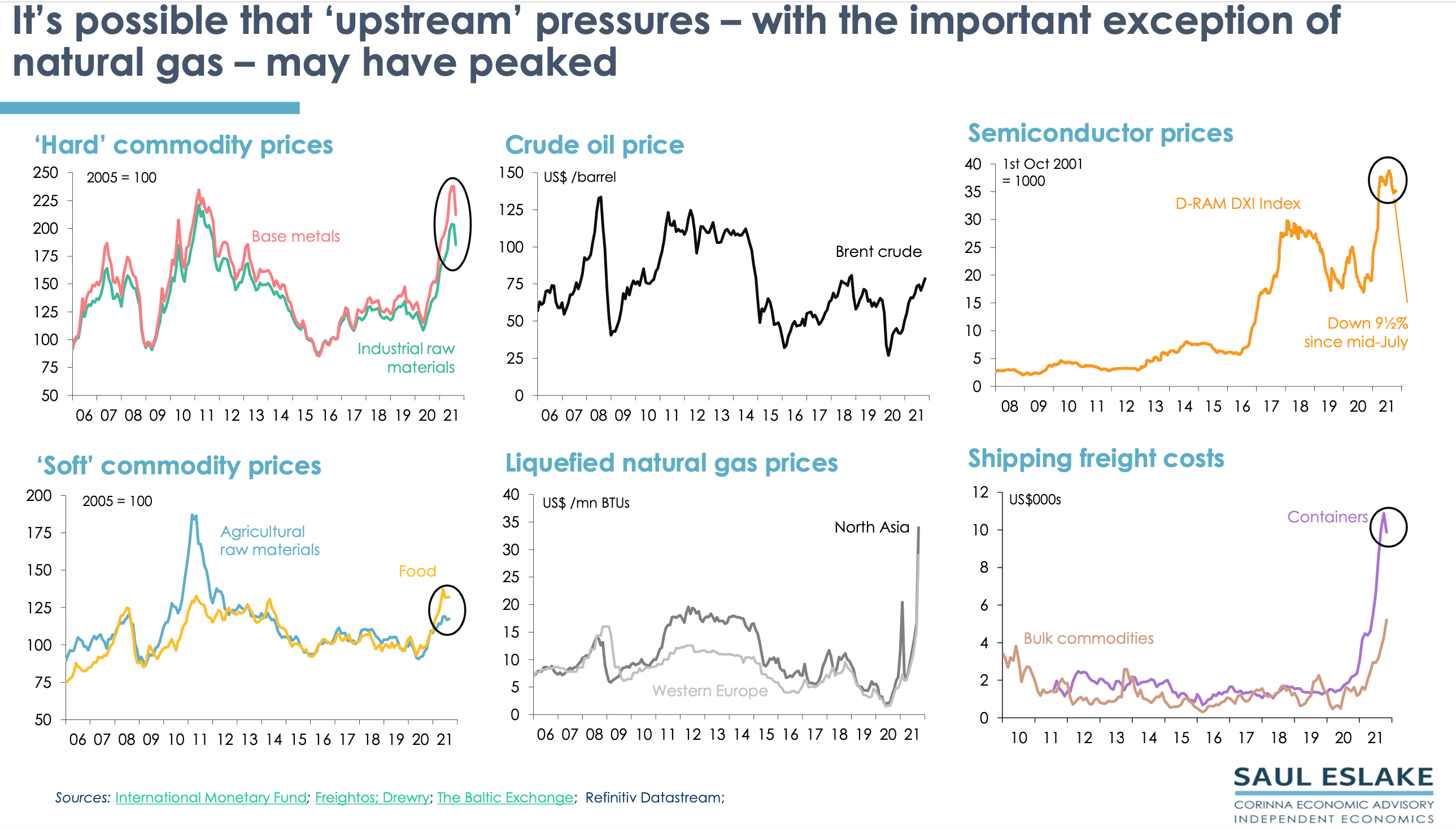

This is one of a half-dozen “upstream” pressures highlighted by economist Saul Eslake during a webinar hosted by fixed-income fund manager Jamieson Coote Bonds.

In his presentation, Eslake sought to outline how seriously (or not) he regards the threat of inflation. And he’s firmly positioned in the “transitory” camp, as it turns out. The sky-high shipping costs alluded to above are one of the main reasons for this view, alongside elevated commodity prices.

“Three-quarters of the increase in inflation in the 20 largest economies of the world this year was attributable either to higher commodity prices or higher shipping costs,” he said.

“And we’re starting to see evidence that the upstream prices of commodities (the prices paid by producers, not consumers) have peaked.”

The chip drought has broken

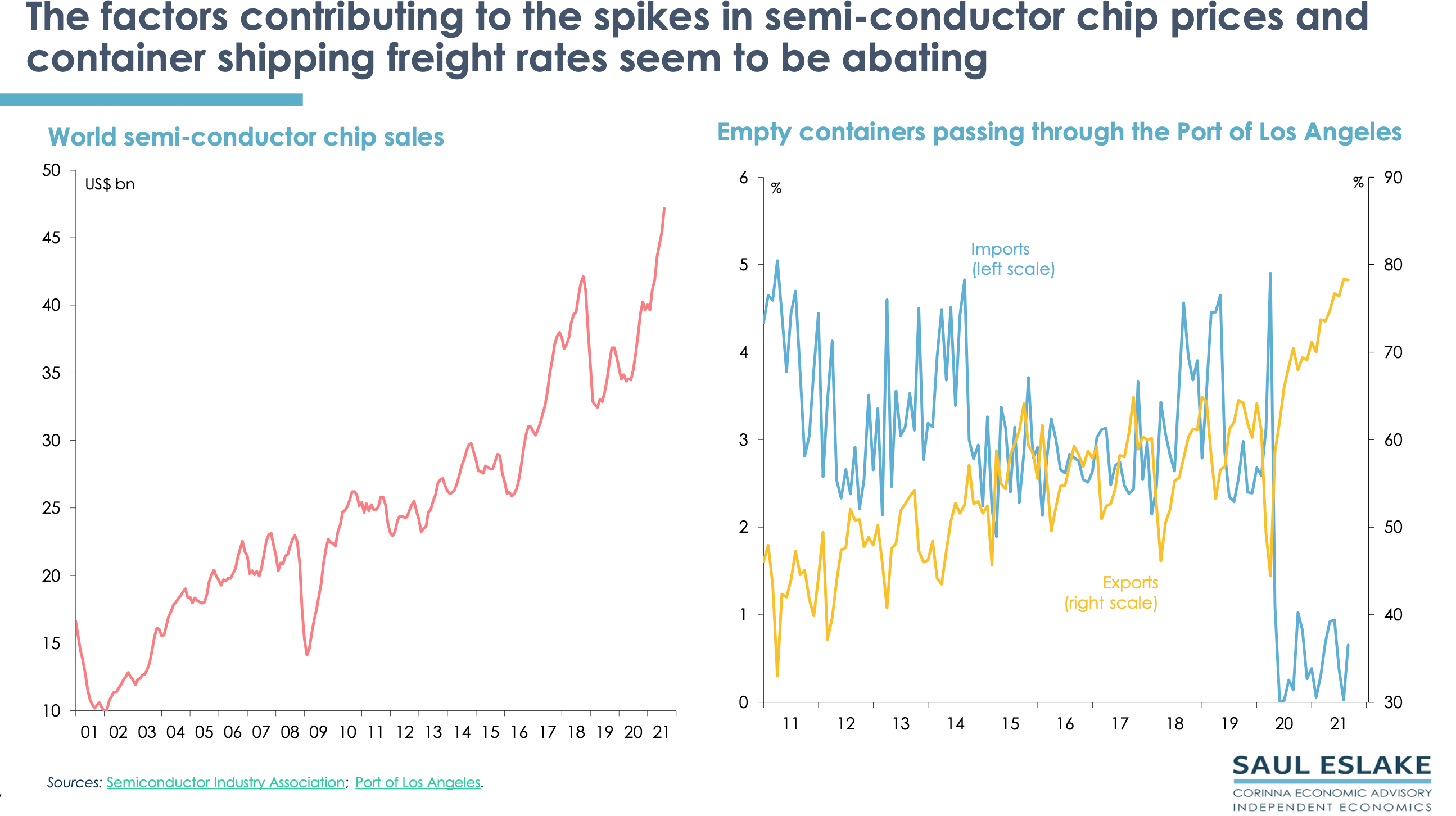

Semiconductors are another base-level product highlighted in the list whose prices he suggests may be starting to trend down again. The spike in the price of microchips – which are core to an ever-expanding array of products including automotive vehicles – was driven by the crippling drought that shut down large factories in the world’s highest-volume chipmaking nation of Taiwan, alongside fires in key semiconductor manufacturing plants in Japan and the US.

But with the drought in Taiwan having ended in recent weeks, Eslake points out that semiconductor production is starting to ramp up again. “Which is probably why semiconductor prices appear to have peaked,” he said.

“And if we look at what’s happened in shipping, the reason for the sharp increase in container shipping charges has been a highly unbalanced pattern of international trade that’s emerged since the opening up of the world economy in the third quarter of last year,” Eslake said.

“You had a lot of containers piling up, particularly in the west coast of the US where there’s nothing much to put back into them. And a shortage of containers at key export ports in places like China, other parts of Asia and to a lesser extent in parts of Europe."

He suggested it is probably too early to be confident that is starting to ease, though the number of ships lining up outside places like the port of Los Angeles has lessened in recent weeks: "But hopefully the worst of that source of upward pressure on inflation is over.”

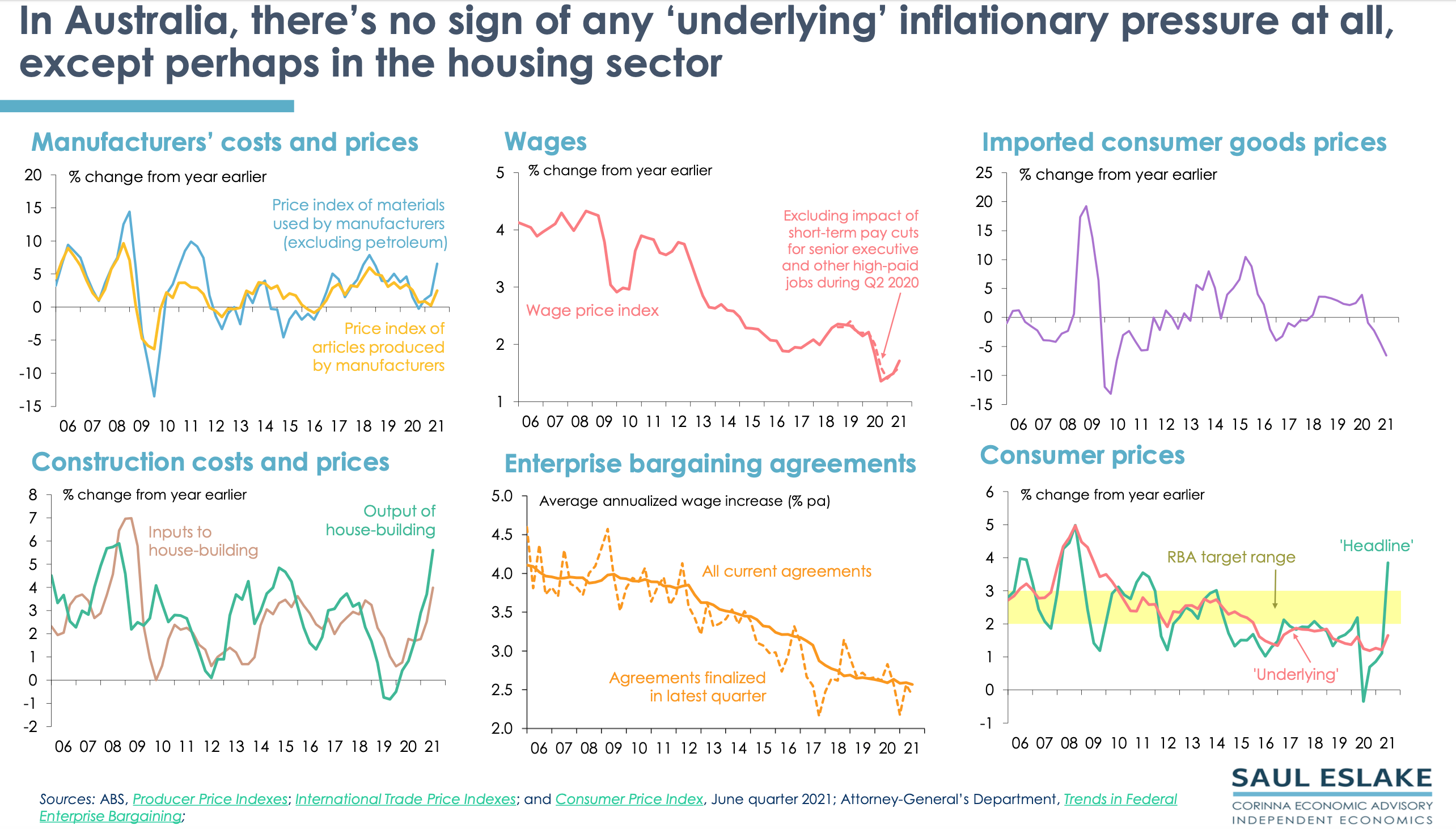

A view that the current lift in inflation is being driven mainly by the prices of consumer durable goods is an overarching theme emphasised by Eslake.

Worsened by supply chain pressures created by COVID lockdowns, these are highlighted in the delays that manufacturers face in accessing raw materials for production. The lead times for materials are currently the longest they’ve been since 1987.

“If it is right that the sudden escalation in the prices of motor vehicles and other electronics-intensives goods has reached its peak, that’s an important reason supporting the confidence that central banks have been expressing, across the advanced world, that this source of pressure on prices is likely to be transitory,” he said.

“Few signs of wage inflation”

Eslake also believes the lessons of history bear out this view, referring to the high inflation scenarios of the 1970s and early 1980s in the US and UK. Comparing that period to now, he sees a strong link between the growth in labour costs outstripping productivity gains both then and now.

“You wouldn’t have had the higher inflation that we saw during these periods if there hadn’t been, as an integral part of that inflationary process, a dramatic acceleration in wage and labour cost inflation,” he said.

“Probably the most important element of the judgement that central banks are making, with which I mostly sympathise, is that there are very few signs of broadly-based wage inflation.”

Housing is Australia’s outlier

Focusing more closely on Australia, Eslake said there are almost no signs of any underlying inflationary pressure except in the construction sector. This is mainly because of government policies such as first homeowner grants along with very low interest rates, where we clearly do have signs of excess demand. “And it wouldn’t be surprising if the inflationary pressures that we see in the construction sector become more attenuated in the next six months or so.”

But otherwise, upstream prices as reported by manufacturers, there’s no sign of inflationary pressure, said Eslake. “And the RBA keeps saying they don’t expect there will be signs of inflationary pressure until they say 2024 – I think it could be 2023, but that’s still a way off.”

“At least as far as the ‘across the docks’ prices of consumer goods are concerned, they’re still exercising downward pressure on inflation. So, there’s very little reason for the RBA to be concerned about any near-term upward pressure on inflation.”

But what if?

Though Eslake regards a longer-term lift in inflation as unlikely, he also outlined some of the major risks investors could face if he’s wrong. These include:

- Elevated energy prices, which could in turn start to hit households and businesses.

- The decarbonisation “net zero” policies being widely pursued could have wider and longer-lasting effects on inflation.

- An excessive focus on the security of supply-chains – in the name of sovereignty – could lead to sustained rises in costs and prices

- Immigration restrictions, which would tighten labour markets more quickly than central banks are currently expecting.

The “priming” effect of the GFC

Mark Burgess, chairman of the Jamieson Coote Bonds advisory board, explored some of the implications of the above points for fixed income investors.

Burgess framed his discussion with the observation that over the last 18 plus months, governments and central banks were far better prepared than during the Global Financial Crisis.

“Central banks learned back in 2008 what to do in a crisis, so they were very primed and could act very quickly,” he said.

Burgess noted that even at the US Federal Reserve meeting at Jackson Hole in 2019, the Fed reminded governments that in the next crisis it would need fiscal support – a reminder that proved extremely prescient given what occurred in March 2020.

“This time around it was very obvious what was needed. For example, governments stepped in with mortgage relief and changed bankruptcy laws – all of which contributed to markets looking through the crisis,” he said.

But the broad-based response of fiscal and monetary policy has also meant that market valuations have become very stretched.

“The market has lifted all boats and this talks to how we should respond. And when you get a lift in all boats, that’s a highly correlated outcome, which leaves us with a dilemma,” Burgess said.

“One of the challenges for bond investors is that, with such high valuations, you almost don’t want anyone to give your money back at the moment.”

Where do you invest next?

“The reinvestment problems become really significant, and this is a real problem for institutional investors and retail investors alike – where do you put the next marginal dollar for your portfolio?”

Burgess believes the key question going forward will be the policy response. He suggests central banks have a general idea of what they need to do but are less confident about the process of repositioning to try lifting interest rates slightly.

“They’ll be reluctant to try and lead the market back up in an aggressive way because they’re worried about the volatility that will create,” he said.

“It’s also very uncertain in the fiscal environment. For example, I don’t believe that anyone has given up on the politics of reducing deficits or the politics of being worried about debt on balance sheets, so we don’t yet know how fiscal policy will respond.”

In Australia specifically, Burgess recognised the hardships and tragedies that hit many people very hard. But in market terms, he noted we’ve had “a relatively good COVID and will come out of this in pretty good shape.”

But the main considerations moving forward include:

- Immigration, particularly from China, and how much damage we’ve done to our largest export market.

- The role of ESG and climate. Even during the COVID period, institutional investors have become very focused on “the right kind” of investing. The challenge here is the potential for the crowding of capital as it moves into ESG, which could ultimately result in lower rates of return.

And while conceding the irony after the profound volatility of markets since last March, Burgess also suggested investors have become used to lower economic volatility over the last 30 to 40 years.

“People have become used to somebody stepping in – that’s why the market rebounded so quickly this time,” he said.

“But there are signs the low economic volatility market might be getting stretched at the margins. If you have high debt on your balance sheet, high volatility is not something you want around you.”

In this context, Burgess referred to volatility in a broader sense than purely as it relates to markets, alluding also to the debt problems (for example, Evergrande) in China and the geopolitics between the Asian powerhouse and Australia.

“With China working to restructure its economy, that could be very volatile if they make a mistake. Fixing a real estate bubble or misallocation of capital can be a very dangerous and fraught issue,” Burgess said.

“And in Australia, we will be affected if China has a much lower growth profile ahead.”

What does this mean for your portfolio?

While it might seem simple but isn’t really, Burgess says investors need to go back to their processes.

“The smart money starts to think about how to rebalance during these good times in markets,” he said.

In trying to determine what is going to create true portfolio diversification in the current environment, Burgess said institutions are putting a lot of thought into the problem but coming up with few answers.

Part of the consideration needed is to think about your portfolio weighting to Australia versus the rest of the world.

Regarding interest rates, he notes this year is the 40th anniversary of rates hitting their peak in 1981.

“Since then, we’ve had a secular decline in rates, which creates a series of habits or behaviours," Burgess said.

“There would never have been a better environment for long-duration assets and property investment in a portfolio, simply because of the trend.

“But in the next decade rates will probably trade sideways. In that environment, the rates will no longer be the supportive element for your investment returns."

Instead, he believes returns will be driven by the quality of assets, the quality of the investment manager choosing those assets, the style of assets selected and the way you time the cycle and think about things like duration in your portfolio.

“Those things will be far more important than the 40-year tailwind (of interest rates) that we’ve all had.

“COVID gave another kick to the decline in rates but we’re back to where we started with rates now likely to go sideways or down, so your technique of investing will be far more important than it has been.”

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire. Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

4 topics