Short and sharp: what if it all goes wrong?

Global markets have started 2021 with the same enthusiasm for the global reflation trade that has been driving markets since November of last year. We too are focusing on this longer-term recovery theme and with vaccine distribution underway, countries should gradually return to pre-crisis activity levels. We expect global GDP growth to recover sharply as the second virus wave fades and vaccination rates pick up.

Supporting this vaccine-driven reflation theme will be continued central bank support. We anticipate central banks to keep interest rates loose, liquidity abundant, and for balance sheets to continue expanding this year, albeit at a slower pace than last year’s stratospheric increase. A perfect recipe for risk assets.

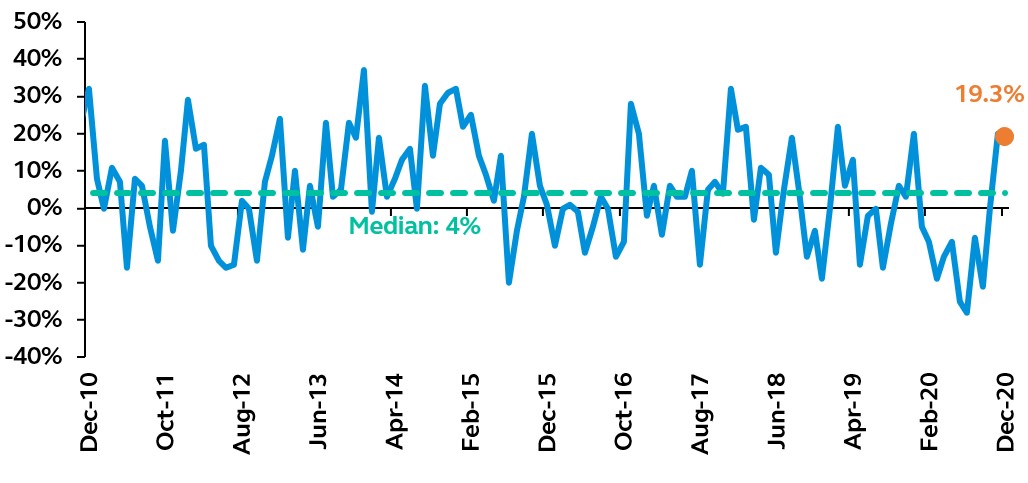

However, the dismal economist in me keeps whispering “what about the risks?” Certainly, one distinguishing feature of this so-called “everything rally” is that complacency is high and positioning is extended. Everyone is sitting on the same side of the table.

Market sentiment

Bulls-bears spread, percent, December 31, 2010 – December 31, 2020

Source: American Association of Individual Investors, Principal Global Investors. Data as of December 31, 2020. The AAII Sentiment Survey is a weekly survey of its members which asks if they are “Bullish,” “Bearish,” or “Neutral” on the stock market over the next six months.

“Everyone is sitting on the same side of the table.”

That phrase should fill investors with unease. Ultimately, the key factor supporting market optimism is the vaccine rollout and while the market seems oblivious to it, until herd immunity is reached, coronavirus remains the primary challenge facing the global economy.

So far, vaccine distribution appears to be running somewhat successfully and, while it is a little slow, governments are directing significant resources towards accelerating the pace of the rollout. But there is still so much that can go wrong! What if side effects start to emerge, deterring people from taking the vaccine? What if immunity doesn’t last for long? Most worryingly, additional severe virus waves are possible if there are any missteps in vaccine distribution or if new variants, such as the ones found in the UK, South Africa and now Brazil, begin to emerge more rapidly.

Then, for the global economy, the prospect of a return to normality would be promptly replaced by additional job losses, increased bankruptcies, and deeper economic scarring. The additional cash borrowed by companies expecting earnings to pick back up soon could prove to be too little to see them safely through to the other side.

In fairness, this specific scenario may sound far too pessimistic. Nonetheless, unexpected shocks do happen and with interest rates in so many developed markets close to their effective lower bounds and central bank sovereign bond holdings already so significant, it is worth asking how policymakers would address the next macro crisis.

What would policymakers do next?

If they haven’t already, central banks could take policy rates below zero, but would likely be met with significant resistance. Slashing rates has distorted financial markets, crippled bank lending, and threatened pensions systems worldwide. Indeed, the Federal Reserve has clearly signalled its reluctance to take policy rates into negative territory, arguing that it is counterproductive.

Another possibility central banks could employ is explicit yield curve control—capping longer-maturity yields by committing to buying whatever amounts of government securities would be necessary to cap the rate. However, it is difficult to effectively cap longer maturity yields and, moreover, when interest rates are already so low, the effectiveness is questionable.

Resolving liquidity strains is certainly one area where central banks could potentially intervene. Yet, while that could help immeasurably for capital markets, that would do little for the underlying economy.

So then, with monetary policy in developed markets operating at the limits of what it can do to meaningfully stimulate demand, the challenge of engineering a recovery would have to fall to governments. Indeed, as Fed Chairman Powell said when the Fed initially cut rates nearly to zero, “Monetary policy has a role… we do think fiscal response is critical.”

Governments, however, are becoming increasingly uncomfortable with their growing mountains of debt. In the U.S., although a new COVID-19 relief package was approved at the end of last year, it took some four months of debate and discussion. Even now, with the Democrats in control of Congress, an additional fiscal stimulus package will likely be smaller and more limited than what President Biden originally hoped for due to opposition from the Republicans.

Rather than go at it alone, central banks may choose to join forces with the government, using their balance sheets to purchase sovereign debt on the primary market, suppressing interest rates and facilitating government borrowing. While the Bank of England is currently utilising that strategy, the Fed has voiced its clear objections, citing concerns about blurring the line between fiscal and monetary policy.

The situation for emerging markets differs significantly as many of them still have room to ease monetary policy. However, rising inflationary pressures would likely render many of them reluctant to cut interest rates further, and high levels of sovereign indebtedness means prospects for further fiscal spending would be limited. Indeed, even as many emerging countries continue to struggle through the pandemic with soaring case numbers, they have chosen to reopen their economies rather than resort to additional policy stimulus.

Investment implications

If a global growth scare did materialise, it would surely stop the reflation rotation in its tracks. Cyclicals and value—only just enjoying a resurgence—would revert to weakness and defensives and growth would likely prosper once again.

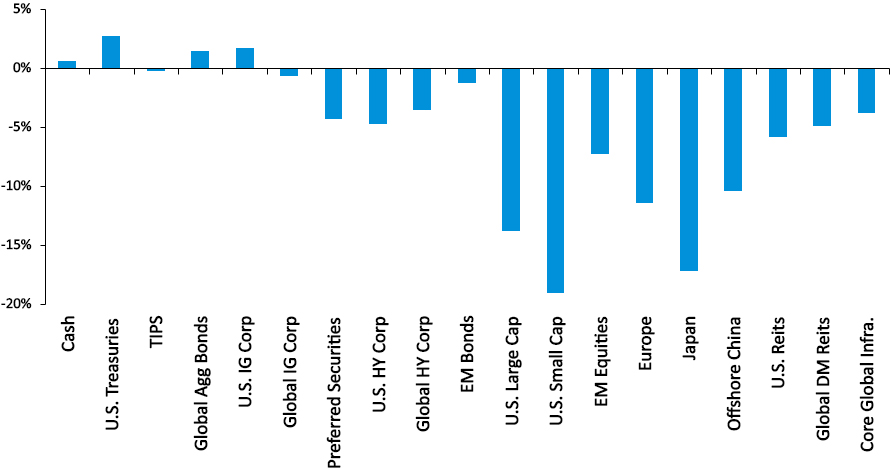

How asset classes responded to the Q4 2018 growth scare

Percent, total return

Source: Bloomberg, Principal Global Investors. Data as of December 31, 2020.

Our analysis shows that during the growth scare of Q4 2018, equities generally underperformed with most indices dropping sharply and U.S. small cap and Japan falling the most. By contrast, fixed income, including sovereigns and global investment grade credit, all recorded positive gains over that period. If investors are worried about the current outlook and believe that growth and earnings forecasts are simply too optimistic, retaining an appropriate allocation to fixed income is sensible.

Instead of fearing a growth scare or being outright bullish, investors are better off staying diversified across sectors, styles, regions and asset classes in order to benefit from any upside, but also protect themselves from the downside risks that continue to threaten markets.

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.