Should Mr Market get a seat at the private table?

“In the short-run, the market is a voting machine – reflecting a voter-registration test that requires only money, not intelligence or emotional stability – but in the long-run, the market is a weighing machine.” Warren Buffett (1993 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter quoting Benjamin Graham)

Benjamin Graham, in The Intelligent Investor, introduced the character of Mr Market. Mr Market is mercurial. He is bipolar, moving from extreme euphoria to deep depression. Along the way, he’ll offer to buy or sell assets strictly at your option.

Indeed, every day, Mr Market turns up at your doorstep and offers to buy your share portfolio or sell you more. Depending on his mood, he’ll offer you a different price. On days he is pessimistic, you might be able to pick up some shares cheap. On other days, when jubilant, he’ll buy them off you for record amounts (if you’re willing to sell!). From one day to the next, it is not always clear what drives his offers, except his sentiment that day.

While we are used to Mr Market turning up on our doorstep quoting us for our share portfolio, imagine for a moment if he turned up at your house every morning to offer you a price on your home. It is not hard to see why this would become a fairly unpleasant state of affairs. While you can always ignore Mr Market’s offers, with a large, long-term mortgage, daily updates might start to fray the nerves. “Is the offer he made today really reflective of the value?” You may find yourself asking in your more private moments.

Benjamin Graham’s point was to underscore the traits of public markets. When prices are subject to constant trading, they may not always reflect intrinsic value, but aspects of human sentiment and groupthink too.

Not so private, private equity

Day-trading has long existed in company shares and is now taken for granted. Shares can be bought and sold in seconds. Those who work within public markets, be they companies or fund managers, are subject to the constant whims of Mr Market. The swing in mood, fed by a constant stream of pricing data, news cycles and demand for regular dividends, is the field in which many investors and fund managers must engage. It is easy to understand, with all this noise and ease of trading, how investors can be tempted by sentiment. In other words, if Mr Market’s mood rubs off on an investor, they may sell when prices are low and buy when high.

Over the last decade or so, there has been an intense focus on the democratisation of private markets. This is a welcome development, but not without its complications.

Listed investment companies (‘LIC’) are a convenient way to access private equity for investors (typically used by those who do not qualify as a wholesale client i.e. sophisticated investors, or who cannot meet the high minimums to invest directly). The shares in the company are traded like any other on an exchange, but the underlying assets of the company comprise private market investments.

Traditional private equity, which has typically been illiquid (usually for 10 years or more), has been wrapped in a liquid structure. In other words, Mr Market has been well and truly invited into the space. This method of democratisation has given rise to a rather perplexing trend: the propensity for LICs to trade below net tangible assets (“NTA”). In other words, the value of the shares in the company trades at a discount to the value of the investments it holds.

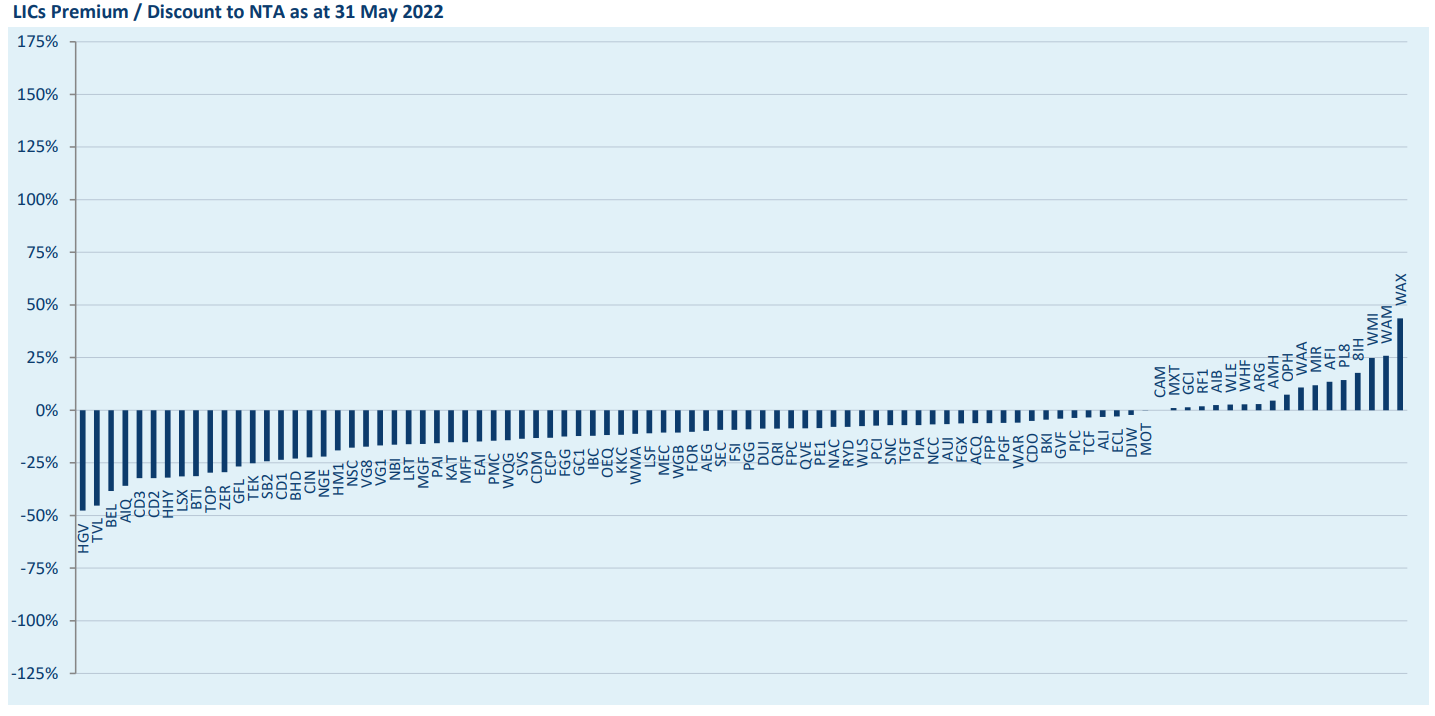

The following chart shows the prevalence of ASX LICs trading at a discount to NTA as at 31 May 2022:

It is curious that the number of LICs trading at a discount to NTA far exceeds those trading at a premium. While 4 of the 5 largest LICs trade at a premium, those LICs trading at a premium (with the exception of an Australian debt fund) invest in liquid shares. In other words, all private equity LICs, including hybrids, are trading at a discount (as at 31 May 2022).

This apparent phenomenon has been observed over time and is not just restricted to private equity LICs.

Why the Discount?

Why is this the case and what does it mean for investors accessing private equity?

To start, it is important to consider the difference between NTA and share price. While the share price is set by the market, NTA is calculated by the manager or underlying manager(s) either directly or through an independent valuer as follows:

NTA = retained realised returns

+ unrealised valuations of the underlying businesses

- liabilities including tax, fees, expenses and any performance fees accrued or payable.

In relation to unrealised valuations, this includes the value of any liquid or illiquid holdings. In the absence of a quoted price, illiquid assets valuations are subjective but based on the Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) Guidelines (or should be).

The calculation is not an exact science but unlike the real estate agent hoping to sell your house, there is generally no incentive to overstate these. Even still, reasonable people may disagree as to whether NTA reflects intrinsic value and investors may simply take a different view.

However, to dig beyond valuations, there may be a variety of reasons for the discount. These reasons can be broadly broken down into market and private equity features.

Market Factors

When it comes to investing via the stock market it seems size matters. Small market capitalisation often results in thin daily volumes and low liquidity. This means any movement can have a significant impact on price.

Traditionally, private equity returns are mostly generated from long-term capital growth. Cash generated from an underlying company is often reinvested to grow the company in preference to a distribution. LIC dividends are therefore reliant on the sale of an underlying investment often leading to lumpy, low or even non-existent dividends, in certain market conditions.

Further, the timing of listing may impact on the return, particularly if the listing is just prior to a market downturn. Take Redcape Hotel Group, whose portfolio listed in 2018 prior to COVID shutdowns and delisted in 2021 following trading at a persistent discount.

Finally, perhaps it is just a matter of perception and sentiment. The perceived wisdom is that listed private equity always trades at a discount to NTA and, therefore, it does.

Private Equity Specific Factors

In relation to private equity LICs, there might be some additional reasons.

Investment horizon

First, private equity is a long-term investment, more akin to ownership. Many underlying investments are held for five or more years, requiring a high degree of patience before returns materialise. LIC reporting focuses on much shorter time frames. Additionally, private equity LICs generally do not have the very long history of many listed companies or established listed equity LICs.

(In)visibility

Secondly, some listed private equity investments start their life as cash boxes with no visibility on what the future portfolio will look like. When acquisitions start occurring, it may be different to investor expectations. Over time, this will gradually change but even many years after establishment, many funds may not be fully invested.

Disclosing information

Thirdly, financial reporting is amalgamated and many of the underlying investments are not household names or able to be referenced on a listed market. This can leave investors with a less than full understanding of the underlying risks. In the absence of this information or difficulty accessing it, the market may take a conservative approach to valuation.

Valuation cycles

Private equity valuation cycles are typically quarterly. In Australia, these valuations can take up to 6 weeks (with offshore managers often taking longer). This lag creates an interesting dynamic in a rising market. The lagged nature of the valuation cycle coupled with a discount to NTA can result in a “double discount” or deep value stock if you have confidence in the NTA.

Everything else being equal, listed private equity LICs should trade at a premium to NTA in rising markets. Conversely, when markets are falling, the NTA may be overstated for a period, depending on the interplay between market movements, NTA and receipt of underlying valuations.

Investor sentiment

Finally, private equity has traditionally been ‘private’, and it is hard to shake this perception. While this has become less so over the years, press articles often portray the sector negatively, which may lead to a change in investor sentiment.

Private Equity is not really listed equity

The democratisation of private market funds is one of the most important financial changes in the last couple of decades. However, it is important that investors are aware of the different formats in which it can be bundled. It is not that one way is necessarily right or wrong, there are simply trade-offs.

It is difficult to overstate the long-term nature of private equity investing. If you want long-term capital appreciation, you have to hold on to it. Private equity is typically not a get rich (or poor) quick scheme. It requires patience and an ability to look through the short-term noise, which doesn’t necessarily sit comfortably within the listed landscape, where NTA is reported monthly, continuous disclosure rules apply and information flows are lagged. The listed landscape is the favoured domain of Mr Market. In uncertain times, unless you like him coming to your door every hour, when it comes to long-term private markets/equity, do you need it? You may sleep better at night if he came to your door a little less frequently. This can be one of the benefits of diversifying your portfolio in non-listed private markets.

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

And you can follow my profile to stay up to date with other wires as they're published – don't forget to give them a “like”.

This article was co-authored by Sam Phillips, CEO of Reach Alternative Investments and Joanne Hordicek, Portfolio Manager at Pomona.

4 topics