Should you fear the big, bad default cycle?

For a journalist, I have a peculiar distaste for stories that deliberately arouse fear. It's probably why I couldn't hack it in traditional news, and how I, fortunately, fell into finance coverage instead.

Recently, I've noticed that there have been several pre-eminent market commentators who seem to be releasing sensationalised statements and fearmongering pieces on the outlook for the fixed income market - particularly, of an oncoming "zombie apocalypse" and large default cycle within higher yielding fixed income investments.

And while yes, rising rates have obviously taken a toll on Australia's businesses - and will continue to do so - it's important to note at the outset that defaults and insolvencies are not skyrocketing out of control as a select few would suggest.

In fact, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) recently found that "business insolvencies have picked up toward more normal (emphasis added), pre-pandemic levels, including in sectors where cost pressures are acute."

"Banks in Australia remain liquid and very well capitalised. Large capital buffers mean that banks are well positioned in the event that nonperforming loans pick up from their very low levels in the period ahead."

In addition, the RBA found that "non-bank lending has been very strong and it is important that lending standards remain prudent. Banks and non-banks continue to have ready access to wholesale funding."

%20(2).jpg)

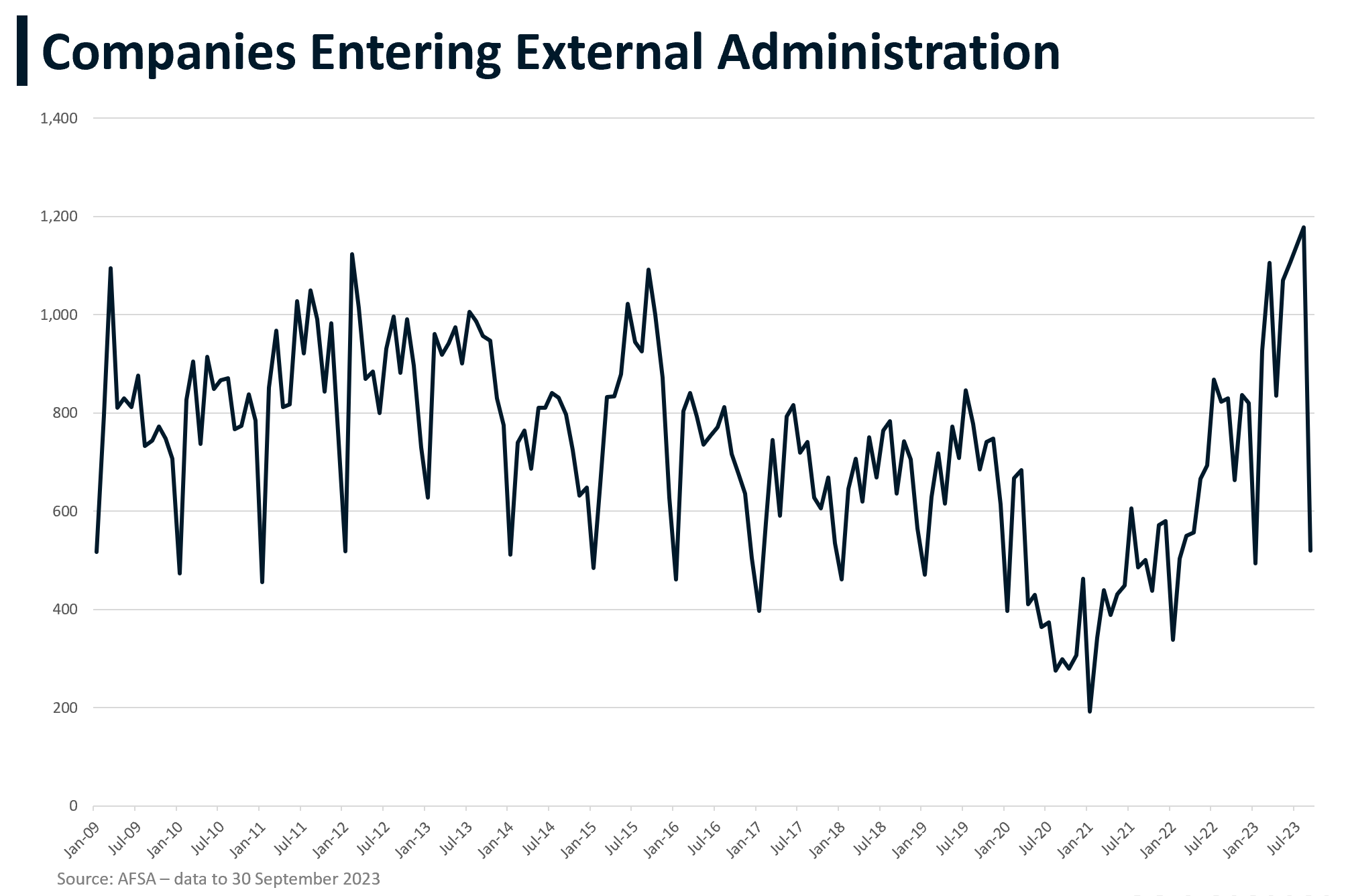

Manning Asset Management's Josh Manning agrees - arguing that while interest rates did come off quite significantly during COVID - meaning there is now a low base that rates can rise from - corporate insolvencies and personal insolvencies are sitting at pre-COVID levels.

"Investors should be looking at the data from a longer-term perspective," Manning says.

"There are, unfortunately, businesses - and particularly smaller businesses, sole traders, partnerships, newer businesses, and companies trading for under three years - that are more likely to go into administration.

"We have higher rates and higher input costs for businesses - like higher wages. No doubt, the environment is more challenging, but we don't see this huge wave of so-called zombie companies going into administration. The data doesn't support that."

As Manning explains, the long-run average of companies entering external administration is typically anywhere between 500 to 1100 a month. Right now, we're seeing anywhere between 500 to 1150 businesses going under each month.

"Now, the average is slightly in the upper bound of that level, but it's not breaking through by any stretch of the imagination at this point," Manning says.

"So, there's definitely pressure out there, but I don't think there is going to be a massive spike."

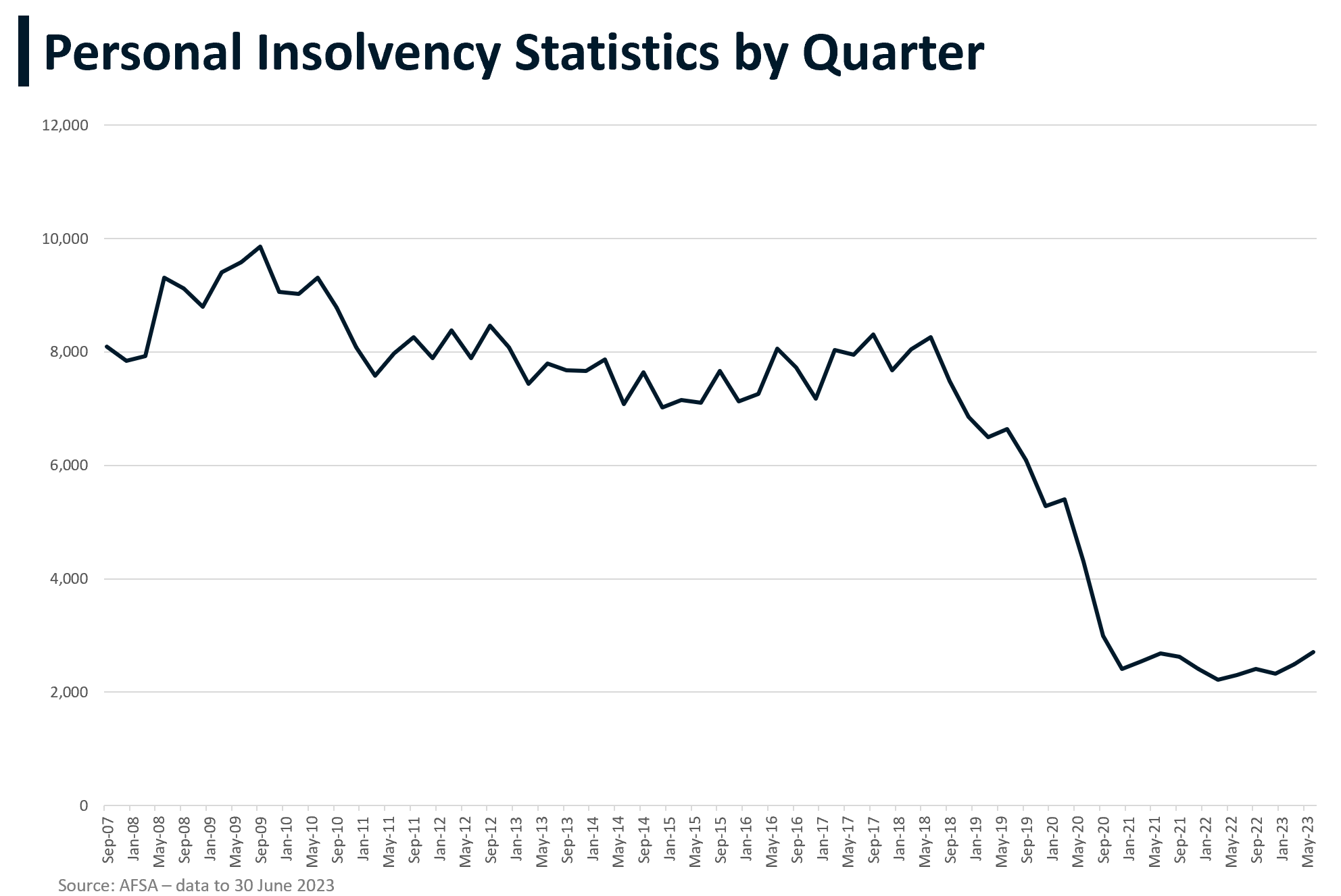

Similarly, personal insolvencies are not exploding out of control.

"AFSA, which is the industry body that oversees personal insolvencies, recently put out some data on expected future levels - and the top range of their bound was only marginally above the longer-term average of personal insolvencies," Manning says.

"Yes, they went through a very low-level period during COVID. And yes, they are rising back up. But we are not seeing a huge spike there either."

At the end of the day, the data doesn't lie.

"The data is not suggesting a wave of defaults or zombie companies," Manning says.

A beginner's guide to fixed income

Given that fixed income can often be particularly complex, Manning and I thought it may be worthwhile to dive into the weeds of the different types of fixed income products that make up the Australian landscape.

After all, as Manning explains, the biggest challenge fixed income managers face is helping income investors understand the full breadth of the fixed income universe - which has changed substantially over the last decade.

Basically, fixed income, private debt and credit is just a loan. The majority of these loans are provided to corporations and consumers by the Big Four banks, but in recent times, a wave of non-bank lenders, neobanks and private lenders such as fund managers have stepped into the fore. Often, banks and non-banks borrow from managers, like Manning Asset Management, rather than the fund manager lending directly to a mortgage holder, for example.

"If you look back 10 years, there were more listed, plain vanilla, corporate, government bond-type strategies. There wasn't a lot of breadth," he says.

"Today, there are all sorts of different credit fixed income products."

These include, but are not limited to:

- Construction finance

- Non-investment grade corporate lending

- Traditional listed bonds

- Structured finance/securitisation

Like in equities, some sectors of the market are more susceptible to issues in a softer economic environment than others. For example, lending to a high-growth, unprofitable company.

"With the RBA cash rate going up, when they need to refinance that loan in two to three years or whatever the term of that loan is, those interest rates they're paying are typically much higher," Manning explains.

"When the interest rate and associated repayment amount is much higher, a company's ability to pay that loan is reduced. These businesses may also be facing headwinds from a revenue or profit margin perspective, either because costs are going up or demand is softening. So that is a challenging space."

Similarly, Manning sees some risk in leveraged finance - where private equity companies will use leverage to "juice up" their expected returns.

"Once again, they face a similar dynamic with some potential cost increases (wages or input costs), and potentially some headwinds from a revenue perspective, squeezing margins as the cost of debt goes up," he says.

"If they've got a large amount of debt, then that once again, is a more risky space."

That said, there are industry standards when it comes to structured finance/securitisation - it's not like a fund manager is just handing over a bag of cash to any business on the street.

"When there are arrears and so forth, there's a very orderly way that they're managed through these structures," Manning says.

"From our perspective, we're not seeing risk limits increasing or things starting to become problematic."

Other areas investors should avoid

While equity investors look out into the future, anticipating what could happen to a stock's share price, credit investors go into a deal with their principal (the initial loan), interest (what they'll receive for lending the money) and term (the time until they get both these back) already locked in.

"We're really cautious about taking interest rate risk at the moment. That's the key."

With this in mind, Manning and his team have a preference for shorter-dated instruments, but they are also avoiding sectors that are highly sensitive to rising rates.

"The market believes that rates have hit their ceiling. However, when interest rates are contractionary like they are at the moment, the pressure is actually building on households and businesses," he says.

"We think investors should just exercise a bit more caution right now until we get more of a line of sight around the implications for inflation, particularly given the conflict in Israel and Palestine right now."

With this in mind, Manning is avoiding construction finance, unprofitable companies, transactions with poor underlying fundamentals, and small consumer loans with lower credit quality (like microfinancing or buy now pay later loans).

"We like traditional asset classes that have performed through many decades in the Australian market," he says.

He points to medium-sized consumer and business loans as an example, as well as short-term (ie. three to five years loans) for mortgages.

4 topics

1 contributor mentioned