Star Gazing

Copernicus wasn’t overly popular with the Catholic church when he proposed the earth orbited around the sun; he was right nevertheless. Challenging the popular wisdom isn’t normally popular. Finance and economics has more than its fair share of theories akin to 16th century astronomy rather than the scientifically proven. One of these is the concept of the equity risk premium (ERP). Much of finance is anchored on the principle of government bonds being the benchmark for the return available on ‘risk-free’ assets. Riskier assets should provide additional returns. The concept is simple and appealing. Answering the questions of what premium equities and riskier assets should offer and whether government bonds will always be seen as ‘risk-free’ is where things get a little trickier. Other than observing long-term averages, assumptions on how much extra return equities or riskier debt should offer aren’t too scientific. If listed equity market data wasn’t around to provide some evidence for professors to torture, there would be questions over whether there is any science in valuation.

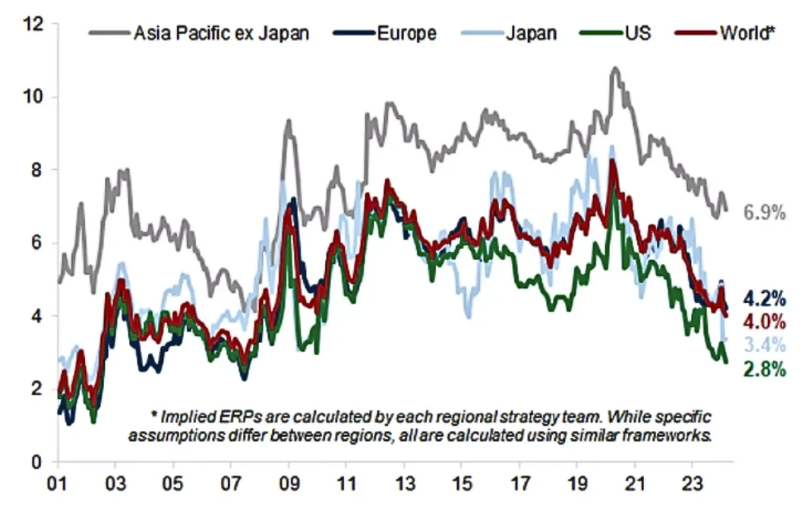

The chart below permits some rough observations; 1) The ERP is all over the place through time 2) The number varies significantly across regions 3) Current levels appear fairly low versus history.

Global market implied ERP (%)

Source: Goldman Sachs, Factset

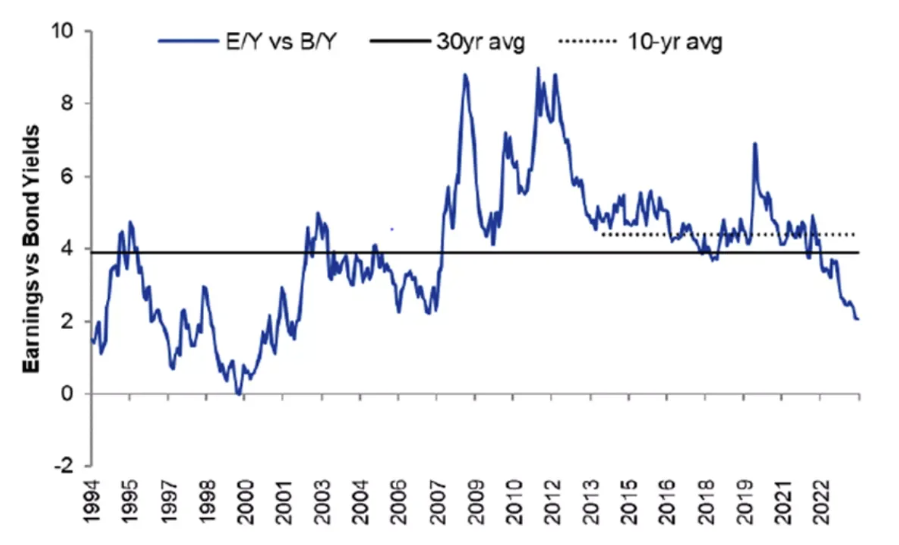

The picture is similar in Australia:

Source: Goldman Sachs, Factset

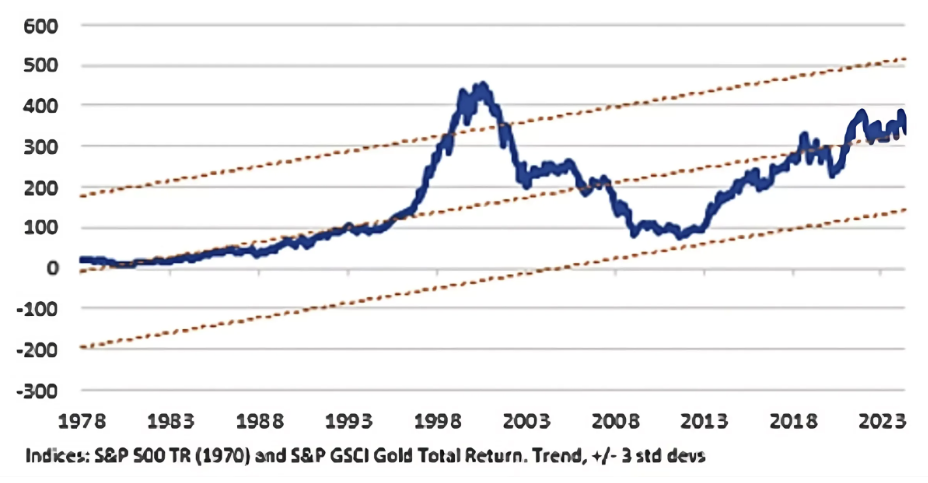

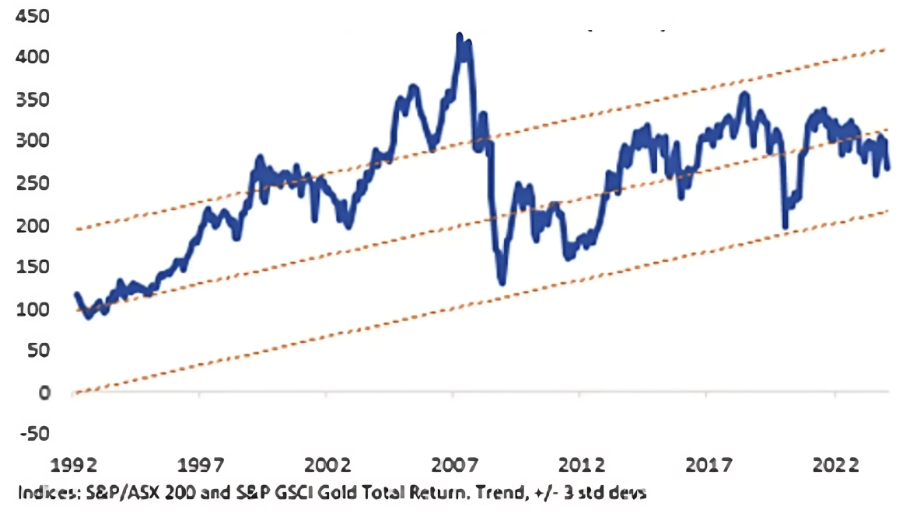

The immediate (and possibly correct) conclusion is that equities are generally expensive versus history. However, in considering alternative explanations, the possibility government bonds are losing their status as ‘risk-free’ investments seems to have some validity. The term ‘certificates of confiscation’ was coined in the 1970’s when inflation ravaged returns of bondholders. As interest rates have risen in response to rising inflation in the post COVID period, bond investors have borne the brunt of the reversal in artificially suppressed bond yields (low interest rates and quantitative easing). The performance of equities relative to gold (charts below) provides another lens suggesting the valuation of equities is far less extreme versus other perceived stores of value.

S&P 500 / Gold

Source: Schroders, Factset

S&P/ASX 200 / Gold (AUD)

Source: Schroders, Factset

Governments the world over, but particularly those in the developed world, are in a tough spot. After a couple of decades in which banking regulation supported massive growth in asset based lending, most countries, particularly Australia, are left with households aggressively geared against residential property and struggling to take on more debt. The erosion of goods and manufacturing relative to services (courtesy of transferring this to lower cost jurisdictions and using the resultant absence of inflation as a justification to lower interest rates) has left economies more reliant on services and asset prices. Supporting asset prices means ensuring an ever growing pool of credit. Enter governments. While Japan is used to the concept of the government spending vastly more than it collects in taxes and funding the difference through issuing debt which is then bought by the central bank, this business model seems likely to become more widespread.

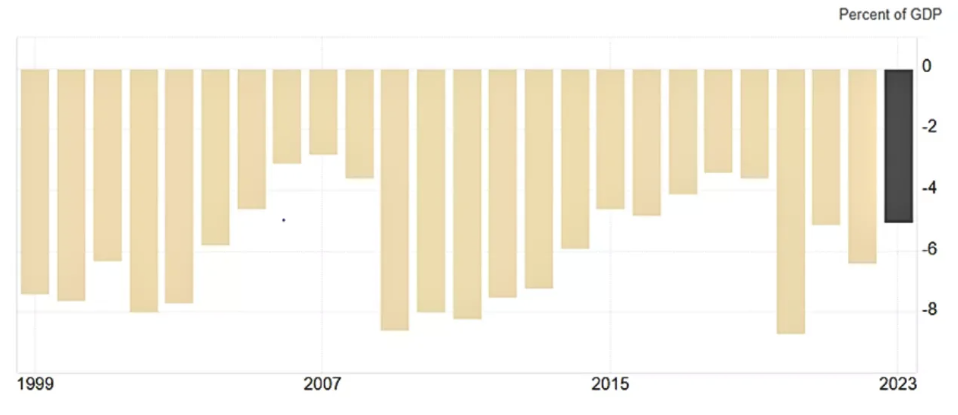

Japanese Government Deficit (% of GDP)

Source: Trading Economics

Jamie Dimon’s recent annual letter pointed out a few factors he thought suggested inflation might be more persistent than anticipated:

“ongoing fiscal spending, remilitarisation of the world, restructuring of global trade, capital needs of the new green economy, and possibly higher energy costs in the future”.

We would agree. All of these are areas in which the government will be expected to shoulder much of the spending burden. In his (generally derogatory) comments on banking regulation, Jamie Dimon also referred to the generally deteriorating relationship between practitioners and regulators, who have generally not been practitioners in business. These comments probably apply to regulation more broadly. History suggests regulation does little to prevent risk and lots to increase cost. As government footprints on the economy become larger, this will almost certainly enhance inflationary pressure. From our perspective it seems likely to be one of the larger threats to strong equity valuations. Interestingly, in trying to understand the myriad of reasons behind the aforementioned differentials in ERP across markets, the gulf between European and US equities is stark. As Nicolai Tangen, the CEO of Norges Bank commented, “in America you have a lot of AI and no regulation, in Europe you have no AI and a lot of regulation”. High levels of regulation and happy investors don’t seem comfortable bedfellows.

As the Australian government wades into supporting solar panel manufacture and quantum computing ventures, dominates new employment as NDIS costs explode and exerts massive pressure on infrastructure and housing as immigration wildly outpaces sustainable levels, the notion of small government trying to remove barriers to private businesses doesn’t seem high on the agenda.

While our preference for focusing on company fundamentals remains, reality dictates the outlook and sustainable level of earnings for any company is inextricably entwined with the operating environment.

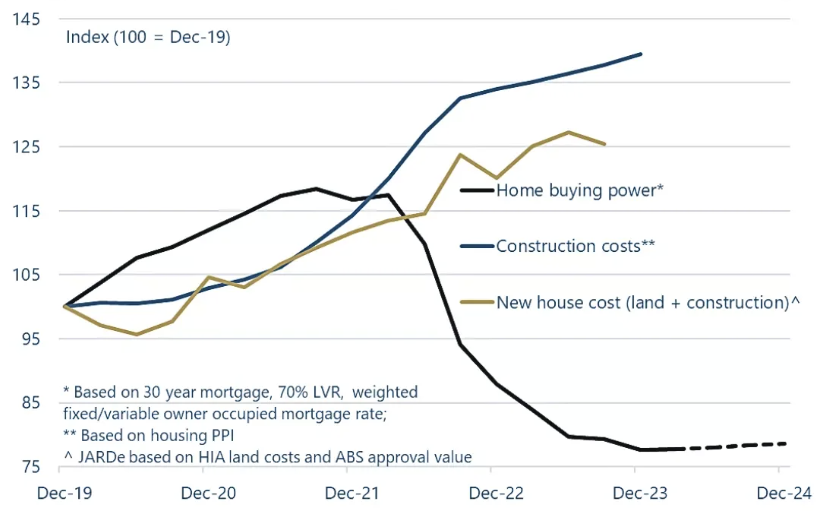

Housing and construction are obvious cases in point. The message from a range of meetings with developers in the past month was consistent. Performance in WA and Qld remains solid as land prices allow developers to produce product which buyers can afford. NSW and Victoria are stuck at a sustainability impasse. Land and construction costs are substantially beyond any reasonable affordability levels. Nearly all reference regulatory costs and delays as a significant part of the problem and a large component of housing costs. Business models do not work when customers are not able to afford the product and calls for more lenient lending standards are yet another anti-sustainability solution to a sustainability problem. Construction, development and business in general across NSW and Victoria seem likely to face greater headwinds than the rest of the country for some time. Unsustainably high cost structures can only be rectified by reducing costs.

Gap between buying power and housing costs

Source: Jarden

In another example of the complexity in disentangling ‘bottom-up’ company research from exogenous influences in the operating environment and developing a thorough understanding of business sustainability, we have spent much time in recent weeks arriving at a view on the value of IDP Education (ASX: IEL). This business has done an amazing job over many years growing its business and market position in distributing and administering International English Language Testing (IELTS) and placing international students at English speaking universities. In this industry, the cynic could conclude that English speaking universities have morphed more into immigration pathways than educational institutions.

Governments are perhaps naïve in seeing universities as vital export earners rather than extracting a significant immigration tax without contributing to associated housing and infrastructure costs.

This immigration pressure is undoubtedly a major factor in housing pressures, with resultant voter backlash. Additionally, genuinely high quality educational institutions would not normally be expected to pay large commissions to agents to scour the world for potential students (schools don’t pay commissions and neither do Harvard). This situation sits alongside an environment in which the proportion of the population with tertiary education has risen sharply over time (with ever rising student debt suggesting the payback on these degrees is dubious), labour shortages are sharply skewed towards blue collar employment and technological change arguably renders the somewhat antiquated university teaching methods obsolete (a major reason why universities have few capacity constraints).

The less cynical view would suggest none of this really matters; IDP are adept at delivering better quality students than peers, universities will always have a voracious appetite for more students, the supply of students seeking higher living standards is unlikely to dry up any time soon and governments across Australia, Canada, US and the UK are unlikely to change course materially. Increasing competition in English language testing and competition for agents are company level issues which inevitably stem from high margins and long periods of success, creating more food for thought, particularly given the relatively high multiples the business commands. Examples like this where valuation needs to contemplate the probability of significant change versus the status quo continuing, are plentiful. Sustainability has many faces and the risks which others aren’t currently contemplating are always the most painful should they arise.

In our efforts to persuade companies of the benefits of aiming for good rather than big, it would appear BHP (ASX: BHP) weren’t listening. In diagnosing problems which may be afflicting BHP, insufficient size and scale wasn’t on our list. In progressing towards a settlement on the Samarco disaster most or all of the profit ever made from the business will be extinguished (BHP made profits of around $6.5bn in the super-cycle years between 2007 and 2015; BHP’s share of the proposed settlement is US$13bn, albeit mainly paid and provided for already). It is clear there are some downsides to being large and high profile. In an increasingly litigious world where governments are looking to find money wherever they can, size generally isn’t positive. The Anglo bid suggests they are undeterred by historic experience and write-downs. The bid, and most of the assumed value in Anglo is in copper, a commodity in which excitement remains high. In case you’ve been hiding under a rock, copper, as a highly conductive metal, is important to the electrification process in which the world faces trillions in capital spend. Few high grade new deposits have been discovered and grades at most large existing projects are declining. A simple, but appealing picture for the supply/demand balance.

The value of copper assets, as is the case for all commodities, is driven by assumptions around long-run pricing. The BHP bid for Oz Minerals evidenced their optimism on the copper price outlook, as high long-term prices and very strong returns on organic capital were required to support the numbers.

Anglo extends this copper price bet in South America and amplifies a long-term wager on the extent to which governments will allow mining companies to retain these high returns should copper prices stay high for an extended period. Ignoring for a minute the question of whether assets in Peru and Chile should be accorded similar multiples to Australian assets (given our discussion above on risk premia), the implied complacency around governments not seeking to retain a greater share of the profitability surprises us. The bid is complex given BHP has limited interest in much of the residual Anglo asset base, and success far from certain given Anglo have already signalled the bid as being inadequate (knock me down with a feather). Whilst not doubting the importance and power of the electrification theme, we continue to believe it more likely the market will find technology solutions which embrace more affordable and available commodities such as aluminium where most assets still command pedestrian valuations. If it indeed transpires that copper supply can’t match demand, higher prices will not create more supply, it will merely direct available supply towards customers able to pay the most. Large scale M&A based on aggressive commodity price assumptions has not been a happy hunting ground for shareholders.

Market outlook

Market structure and the weightings of index constituents largely reflect historic success and extrapolation of recent conditions. Long history of low inflation and low interest rates has left investors comfortable with very high weightings in financial intermediaries and very high valuations in companies able to conjure persuasive growth stories. These high valuations have continued to prevail in the face of higher interest rates as popular wisdom still dictates an expectation that inflationary conditions are transitory, rather than the new normal. Investing will always be about sensibly assessing probabilities rather than professing unjustifiable certainty on the future. Our assessment sees the probabilities skewed in favour of a future which looks very different to the past couple of decades. As replacement cost of assets rises and investors seek more avenues for inflation protection, the infatuation with intangible assets and ‘capital light’ businesses has the potential to change. Acceptance of government bonds as a ‘risk-free’ benchmark may also.

Public markets have gradually lost popularity over recent years, with litigation and regulation again culprits, alongside the desire for many investors to control their own valuations rather than subject them to the vagaries of the marketplace, which unfortunately means accepting the rough with the smooth. Our tendency to (perhaps too often) challenge the popular wisdom, would suggest sacrificing the vastly underappreciated benefits of liquidity at a time when risks in the world seem to be elevating rather than contracting, could prove painful. Sometimes the popular wisdom can be wrong.

Learn more about investing in Schroders' Australian Equities.

2 stocks mentioned