Super for some

Clime Investment Management

Just before Christmas, the Productivity Commission presented its final 700-page report to the Government titled “Superannuation: Assessing Efficiency and Competitiveness”. The Government released it to the public in early January.

The Commission was instructed to “assess the efficiency and competitiveness of Australia's superannuation system and make recommendations to improve outcomes for members and system stability. The Commission is to also identify, and make recommendations to reduce barriers to the efficiency and competitiveness of the superannuation system.”

However, the Treasurer also instructed the Commission to not review the whole superannuation industry. The Commission noted: “Whilst not out of scope, defined benefit funds should not be a key focus of the Commission's assessment.”

Therefore, the Commission was directed not to inquire into or pass judgement on the appropriateness of the older and massively underfunded Commonwealth and State Government defined benefit schemes. A cynic might suggest a cover-up (and conflict of interest) by members of the Australian Parliament and its bureaucracy, for many remain as beneficiaries of the extreme largesse of these schemes.

It is interesting to reflect that defined benefit schemes were the starting point for pension schemes in Australia. The Commission gave a brief history of pension schemes with the following observation:

“The history of superannuation spans more than 150 years. It began in 1862 with the establishment of a defined benefit pension fund for the employees of the Bank of New South Wales. Superannuation followed this model for the next 100 years: defined benefit pension funds were established for a minority of employees, who were generally higher‑paid white‑collar employees in the private sector or civil servants in the public sector. Many of these earlier superannuation schemes were provided through life insurance companies.

Superannuation changed significantly with the 1985 Prices and Incomes Accord, agreed between the Australian Government and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. Under the Accord, wage increases would be traded off for a 3 per cent employer superannuation contribution from 1986. This was implemented through industrial awards, set by the then Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. It saw the extension of superannuation coverage to most employees covered by awards.

At this point, specific superannuation funds started to be named in awards as part of workplace relations processes. Several industry‑based funds were established as not‑for‑profit entities to cater for employees in specific industries.

The modern system began with the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) in 1992, which extended superannuation coverage to more employees. The SG rate was originally set at 3 per cent of earnings and has increased gradually to its current level of 9.5 per cent (and scheduled to rise further to 12 per cent in 2025). At the time the SG was introduced, the broad objectives were to provide an adequate level of retirement income, relieve pressure on the Age Pension, and increase national savings.”

Why are Defined Benefit Schemes interesting?

It is our view that the significant advantages to beneficiaries that arise inside Defined Benefit Schemes (as they apply to former Commonwealth and State Government servants) should be included in the (somewhat heated) debate concerning the proposed franking changes by the Labor Party. Apart from the burden on all taxpayers to fund the “defined benefit” black hole, the benefits of these grandfathered schemes greatly exceed the benefits of franking to the majority of SMSFs.

To explain this, consider the Future Fund which was set up primarily to fund the defined benefit public servants pension entitlements (pre-2005 employees). The Fund is expected still to be paying out pensions until the late 2040s – some 30 years from now!

Today the Future Fund is not actually paying any pensions despite operating for 12 years. Also, it utilises franking benefits from Australian equities inside its $140 billion of assets. The payment of “indexed” pensions, supposedly the liability of the Future Fund, is still being fully paid by taxpayers and expensed through the Commonwealth budget.

The reason for this is that the actuaries somehow got it wrong when the Future Fund was set up in 2006. They originally forecast that about $120 billion of assets would be enough to absorb the funding liability from taxpayers. Unfortunately, they got that estimate wrong by a “mere” $100 billion and today we can only ponder why. Was this sheer incompetence, or a manufactured conclusion to suit the bureaucrats and parliamentarians who would be the beneficiaries of the Future Fund?

That takes us to an interesting question for franking, superannuation and SMSFs. If the beneficiaries of Commonwealth Defined Benefit Schemes can keep their indexed pensions – even if they are worth many millions of dollars in capital value – then why are SMSF members with less “real” super denied their franking benefits?

Further, if franking rules, established for some 20 years, are to be changed because they excessively draw on the budget, then why should unfunded Commonwealth defined benefit and indexed schemes be maintained?

Maybe questions and observations like the above led the Commission to suggest that Australia needs a fuller enquiry into the funding of super.

“We have not looked at the broader role of super in funding retirement incomes or the impact of super on national savings, public finances or intergenerational equity — broader questions that should be answered by an independent inquiry ahead of any increase in the Superannuation Guarantee rate.”

Indeed, the Commission’s suggestion is very similar to our views published in the AFR and this column (see here - Franking Debate).

Australia has a large superannuation asset base and that is commendable; but is it fit for purpose? Have we truly defined the purpose of our superannuation and retirement policy to effectively measure success or failure? Further, could the superannuation system be better designed so it is fit for purpose?

Given the conclusions of the Productivity Commission, the Government should move urgently to create an Independent Enquiry to review the contributions, benefits, tax benefits and fairness of the entire superannuation system. One benefit of this would be to hold the proposed change to the franking system until a proper review was undertaken.

Charts from the Commission’s Report

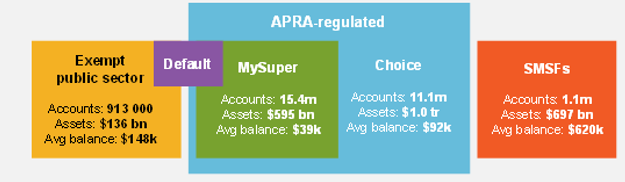

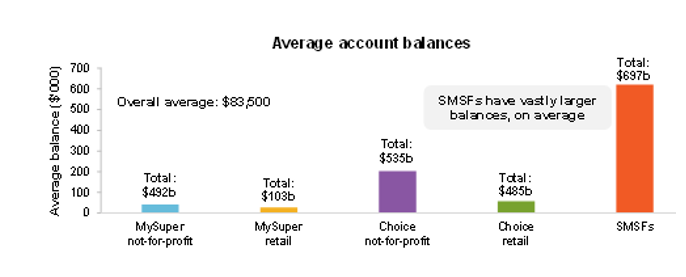

We have scanned the Report and identified the following which may be of interest to SMSF trustees. It is clear that SMSF members have higher balances and are more likely to be appropriately funded in retirement than other segments of the population. The super system works for SMSFs, but not generally for the broader population.

The first chart captures the components of the Australian Superannuation Industry. It shows that average balances (ex SMSFs) are generally too low to comfortably support the retirement of members.

This exemplifies our point made earlier that the beneficiaries of the Future Fund are extremely well-funded in retirement compared to the average Australian citizen huddled into MySuper and/or Choice funds (industry and retail).

The average balance of MySuper accounts is a staggeringly low $38K, but this segment presumably includes millions of young workers who have just started their long-term savings journey. It is these funds that the Commission notes were being eaten into by multiple accounts (for the same beneficiary) and insurance policy premiums for inappropriate policies.

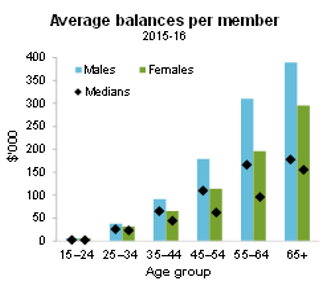

The account balances balloon as members age with an acceleration of balances once people move past age 45 years. However, the table below highlights the wide disparity of balances between males and females. Further, the average balances (quoted below) are greatly bolstered through the inclusion of the SMSF segment.

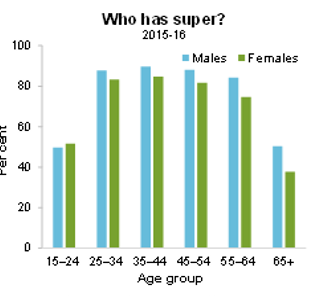

The next table shows an interesting but disappointing feature of accumulation and pension schemes. While more men than women have a super account, it is alarming that so many people have an insufficient accumulation account by size to justify its transference into pension mode. Thus 30% of males and 40% of females decide to cash in super on retirement and presumably decide to fully draw on the Commonwealth pension.

The Report notes:

“Over 90 per cent of member accounts are in the accumulation phase, with the remainder in retirement and holding over a third of the system’s assets in 2015‑16. However, some members withdraw their balances as lump sums when they reach retirement and effectively exit the super system. For example, in 2011‑12, nearly 3 per cent of the population aged 55 and over withdrew more than 90 per cent of their super balances as a lump sum. These are usually members with smaller balances. In general, females withdraw a higher proportion of their balances as lump sums than males.

Of the retirement age members who remain in the system and receive regular income from their super, the median income was $391 per week in 2015‑16, though the median for the typical account‑based pension (which excludes members receiving defined benefit pensions) was lower, at $322 per week.

Overall, a third of Australians aged 65 years and over-rely on Government pensions and allowances for over half of their total income, and only about one‑fifth rely on Government payments for less than one per cent of their income.”

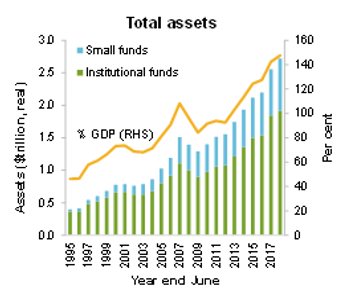

Total assets inside the superannuation system are estimated at $2.7 trillion (or over 140% of GDP). Based on size to GDP, Australia has one of the largest superannuation pools in the world.

However, we question the benefits of such a large pool of superannuation assets that is member account-based, if it is not also supported by a national pension or annuity structure.

To this point, Paul Keating in 2013 made some insightful comments. After noting that he was surprised by the immense growth of SMSFs (which he admitted was an afterthought in the creation of the national superannuation system), he drew attention to likely returns, SMSFs and the total size of superannuation assets:

“I mention this to provide context commentary on the rapid growth of SMSFs. As a general statement, I believe people’s expectations as to rates of fund returns are too high. The Australian superannuation system is both large in world terms and large in absolute terms. Not only is it forecast to grow to $8.6 trillion by 2040, but currently, the system stands at over 100% of GDP and will mature nearer to 200% of GDP. It is simply too large in aggregate to consistently return high single- or double-digit returns.”

Paul Keating – Cuffelinks, February 2013

This is a crucial point because it identifies the biggest problem that confronts the likely returns of large APRA funds going forward. There are dis-economies of scale in investing. So, while costs per member can come down (economies of scale) these will be offset by dis-economies of investment returns as funds become too large to perform at their optimal level.

Indeed, the Commission found in reviewing the eleven-year returns to 2016 that SMSFs on average outperformed APRA funds by 0.4% pa to 1.4% pa. They noted that there are differences in the reporting of returns, but upon a proper review of ATO returns, noted the following:

“The comparison of SMSF and APRA‑regulated fund returns is further complicated by differences in the method used to estimate rates of return in each segment. Indeed, several inquiry participants questioned the validity of SMSF return and cost data published in the Commission’s draft report. Class Limited and the SMSF Association submitted that differences in the approaches used by the ATO (for SMSFs) and APRA (for APRA‑regulated funds) understate SMSF returns relative to the APRA formula. With the assistance of additional data provided by the ATO and Class Limited, the Commission confirmed this to be the case, with the aggregate impact on reported SMSF returns in the order of 1 percentage point a year.”

The outperformance of SMSFs is confused by the excessive, unrelenting and often misleading advertising campaigns of industry funds. Why do they do this when they are already receiving massive flows from default allocations?

The desire of Industry Funds to grow funds under management without an eye or concern on investment dis-economies is something that might catch their trustees’ focus in due course. It was completely overlooked by the Royal Commission, as were multiple account charges and the inappropriate defaulting of their members into insurance policies.

The Commission noted that the SMSF outperformance was probably created by asset allocation and particularly with the strong allocation to direct unlisted property. This is the “unfair” advantage of actively managed SMSFs – the ability to access good quality unlisted investments that generate superior yields and total returns. The ability to be nimble is a clear advantage.

The 2018 numbers are in – a tough year

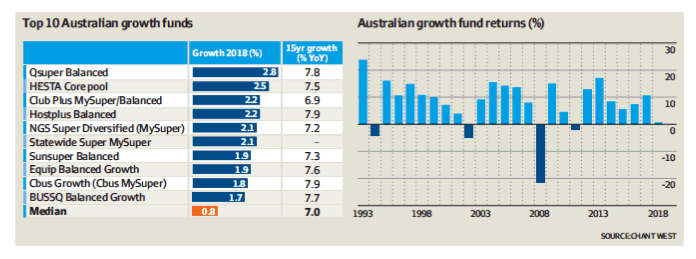

To finish on returns, the 2018 numbers are dribbling in from a range of APRA funds. The AFR quoted last week that from the wide dispersal of investment choices available through APRA funds (growth, income, pension, balanced, etc.), the best performers generated a 2.8% return, the median was 0.8%, and many funds had negative returns.

Longer term, a balanced return of about 7% pa is generated by most APRA funds; based on asset returns, these predominantly came from direct property, income securities (mainly unlisted), infrastructure (unlisted) and international equities.

And - of course - the utilisation of franking credits that they will retain if Labor is elected.

4 topics

The Clime Group is a respected and independent Australian Financial Services Company, which seeks to deliver excellent service and strong risk-adjusted total returns, closely aligned with the objectives of our clients.

Expertise

The Clime Group is a respected and independent Australian Financial Services Company, which seeks to deliver excellent service and strong risk-adjusted total returns, closely aligned with the objectives of our clients.